Introduction

Anterior open bite results from the combined influences of skeletal, dental, functional, and habitual factors. The long-term stability of anterior open bite corrected with absolute anchorage has not been thoroughly investigated. The purpose of this study was to examine the long-term stability of anterior open-bite correction with intrusion of the maxillary posterior teeth.

Methods

Nine adults with anterior open bite were treated by intrusion of the maxillary posterior teeth. Lateral cephalographs were taken immediately before and after treatment, 1 year posttreatment, and 3 years posttreatment to evaluate the postintrusion stability of the maxillary posterior teeth.

Results

On average, the maxillary first molars were intruded by 2.39 mm ( P <0.01) during treatment and erupted by 0.45 mm ( P <0.05) at the 3-year follow-up, for a relapse rate of 22.88%. Eighty percent of the total relapse of the intruded maxillary first molars occurred during the first year of retention. Incisal overbite increased by a mean of 5.56 mm ( P <0.001) during treatment and decreased by a mean of 1.20 mm ( P <0.05) by the end of the 3-year follow-up period, for a relapse rate of 17.00%. Incisal overbite significantly relapsed during the first year of retention ( P <0.05) but did not exhibit significant recurrence between the 1-year and 3-year follow-ups.

Conclusions

Most relapse occurred during the first year of retention. Thus, it is reasonable to conclude that the application of an appropriate retention method during this period clearly enhances the long-term stability of the treatment.

An anterior open bite is a difficult condition to treat in orthodontics. The deformity is caused by combined influences from skeletal, dental, functional, and habitual factors. Various treatment modalities have been suggested for treating patients with anterior open bites, although the condition is typically treated by the orthodontic extrusion of the anterior teeth or a combination of orthodontic and orthognathic surgical treatments in adults.

However, correcting an anterior open bite with anterior extrusion is limited in improving the dentofacial esthetics of a patient with a skeletal open-bite tendency. As a general rule, for enhancing the facial esthetics of a patient with a skeletal open bite, the maxillary posterior segments need to be impacted with a surgical approach. Denison et al corrected open bite by upwardly repositioning the maxilla with LeFort I osteotomy and studied the postsurgical stability of patients with skeletal open bite. At 1 year posttreatment, relapse significantly increased in facial height, and eruption of the maxillary molars and overbite significantly decreased, resulting in a 21% relapse rate. Proffit et al also treated open-bite patients using LeFort I osteotomy and observed their posttreatment stability over 3 years. They reported that 7% of the maxilla-only surgery group and 12% of the 2-jaw surgery group had 2 to 4 mm of overbite reduction.

With the advent of an absolute anchorage, however, it has become feasible to nonsurgically correct an anterior open bite with orthodontic intrusion of the posterior teeth and obtain satisfying results. A number of studies were concomitantly released to introduce treatment methods with absolute anchorages and their results. Kuroda et al noted that it is simpler to treat an open bite by intruding the posterior teeth with skeletal anchorage than to correct it surgically. Sugawara et al also used miniplates to treat patients with anterior open bite by intruding the mandibular molars, but they did not report the long-term stability of the treatment after their last report of a 30% relapse rate at 1 year posttreatment. Lee and Park used miniscrew implants to intrude the maxillary molars and reported a 10.36% relapse rate for the intruded molars and an 18.1% relapse of overbite at 1 year posttreatment.

Because there has not been a substantial report on the long-term stability of treating anterior open bite with absolute anchorage, we evaluated the 3-year posttreatment stability of anterior open bite in adults treated by orthodontic intrusion of the posterior teeth with miniscrew implants.

Material and methods

Our study participants were selected from the archives of the Department of Orthodontics, Dental Hospital of Yonsei University College of Dentistry in Seoul, Korea. Patients who were treated with miniscrew implants to intrude the maxillary posterior teeth and followed for at least 3 years of the retention period were selected according to the following criteria: (1) diagnosed with incisal open bite (incisor overbite: <–1.0 mm), (2) high SN-MP angle (>40°), and (3) skeletal Class I or Class II discrepancy (anteroposteriorly).

Nine patients (1 man, 8 women) met these criteria and were included in the study. Three of these patients had premolar extractions. The mean age at the beginning of treatment was 23.7 years (range, 18.3-31.1 years), and the mean treatment period was 28.8 months (range, 18-37 months). The mean period during which the miniscrew implants were applied was 5.4 months (range, 3-9 months), and the mean retention period was 41 months (range, 36-51 months). All patients were given lingual fixed retainers; the extraction patients applied them between the premolars, and the nonextraction patients applied them between the canines. In addition, they were also given the usual circumferential retainers for retention; the retainers were applied on both the maxilla and the mandible for the entire day during the first 6 months after treatment and only at night after that.

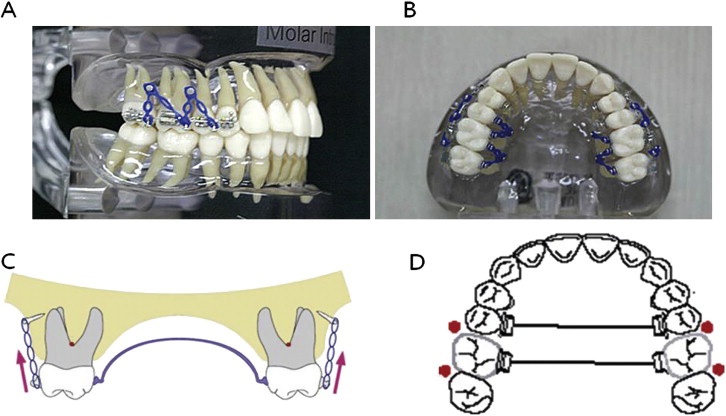

Two methods were used for intrusion of the maxillary molars. The first method was miniscrew implants placed on the buccal and palatal sides, between the roots of the maxillary second premolar and first molar, and between the roots of the maxillary first and second molars. After a 1 to 2 week period, an intrusive force was directly applied on the molars with elastomeric chains ( Fig 1 , A and B ).

The second method was the placement of miniscrew implants on the buccal side only, between the roots of the maxillary second premolar and first molar, and between the roots of the maxillary first and second molars. Rigid transpalatal arches were placed before applying an intrusive force to prevent buccal tipping of the teeth ( Fig 1 , C and D ).

Lateral cephalographs were taken at the Department of Radiology, Dental Hospital of Yonsei University College of Dentistry by using Cranex3+ (Soredex Orion corp, Helsinki, Finland) and stored in digital imaging and communications in medicine (DICOM) file format in the picture archiving communication system (PACS; Infinitt Co, Ltd, Seoul, Korea). The PACS digitizes and manages radiographic images from individual hospitals.

The cephalometric radiographs taken before the introduction of PACS were scanned by using Diagnostic Pro Plus (Vidar Systems, Herndon, Va), corrected for their measurements, and uploaded to the PACS to be included in the study.

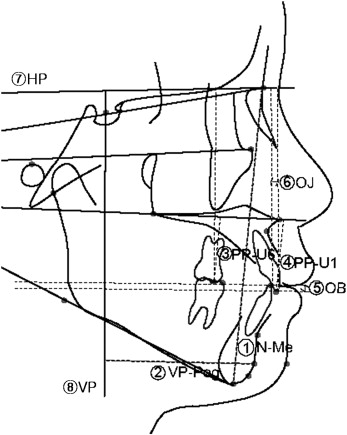

The cephalographs were taken with conventional radiography at the initial evaluation (T1), after treatment (T2), 1 year after treatment (T3), and 3 years after treatment (T4). The cephalographs were traced through the midpoints between the right and left structures, and the measurements were corrected by considering a 110% magnification rate. Cephalometric landmarks, reference planes ( Fig 2 ), and cephalometric variables ( Table I ) were selected based on commonly used analyses.

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Skeletal | ||||||||

| ANB (°) | 4.60 | 1.28 | 3.94 | 1.56 | 3.94 | 1.55 | 4.11 | 1.67 |

| FMA (°) | 38.26 | 3.45 | 35.11 | 3.88 | 35.74 | 4.11 | 35.80 | 4.04 |

| SN-GoMe (°) | 45.44 | 4.11 | 43.41 | 4.41 | 43.68 | 4.88 | 43.98 | 4.76 |

| SNPog (°) | 76.08 | 3.57 | 77.18 | 3.79 | 76.71 | 4.10 | 76.31 | 4.04 |

| AFH (mm) | 133.95 | 5.55 | 131.41 | 6.10 | 131.86 | 5.54 | 132.32 | 5.87 |

| VP-Pog (mm) | 50.10 | 8.40 | 52.50 | 8.54 | 51.75 | 9.55 | 51.13 | 9.13 |

| Dental | ||||||||

| OB (mm) | −3.91 | 1.65 | 1.65 | 0.82 | 0.66 | 0.79 | 0.45 | 1.09 |

| OJ (mm) | 7.23 | 3.68 | 2.90 | 0.78 | 3.36 | 1.57 | 3.31 | 1.49 |

| IMPA (°) | 89.08 | 3.39 | 88.42 | 5.87 | 88.89 | 5.31 | 88.97 | 5.27 |

| U6-PP (mm) | 26.88 | 1.12 | 24.50 | 1.64 | 24.89 | 1.69 | 24.94 | 1.68 |

| U1-PP (mm) | 31.50 | 2.67 | 32.56 | 2.12 | 32.49 | 1.91 | 32.83 | 2.15 |

| L1-MP (mm) | 43.58 | 2.46 | 45.17 | 2.78 | 44.90 | 2.58 | 45.12 | 2.57 |

Statistical analysis

The lateral cephalographs stored in the PACS in DICOM file format were analyzed by using V-ceph software (version 3.5, CyberMed, Seoul, Korea) to measure the landmarks and reference points.

In an effort to maintain consistency, all cephalometric measurements and analyses were done by 1 examiner (M.-S.B.). Once a week, a number of reference points were randomly selected to remeasure and reanalyze the dimensions with paired t tests to verify and reduce systematic errors.

The Shapiro-Wilks test was used to verify normal distribution, the paired t test to compare variables at T1 and T2, 1-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare the values at T2, T3, and T4, and the Pearson correlation analysis to examine their correlations.

Results

The mean measurements for selected cephalometric variables from the T1 evaluation to T4 are shown in Tables I and II , and the correlation coefficients between the variables are presented in Tables III, IV, and V .

| ΔT2-T1 a | ΔT3-T2 b | ΔT4-T3 c | ΔT4-T2 d | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | SD | Sig | Mean | SD | Sig | Mean | SD | Sig | Mean | SD | Sig |

| Skeletal | ||||||||||||

| ΔANB (°) | −0.66 | 0.79 | ∗ | 0.00 | 0.70 | NS | 0.17 | 0.71 | NS | 0.17 | 0.71 | NS |

| ΔSN-GoMe (°) | −2.03 | 1.59 | † | 0.27 | 1.14 | NS | 0.31 | 1.33 | NS | 0.57 | 1.46 | NS |

| ΔSNPog (°) | 1.10 | 0.94 | † | −0.46 | 0.56 | ∗ | −0.40 | 0.72 | NS | −0.86 | 0.92 | ∗ |

| ΔFMA (°) | −3.16 | 1.81 | † | 0.64 | 1.41 | NS | 0.05 | 0.86 | NS | 0.69 | 0.88 | ∗ |

| ΔAFH (mm) | −2.53 | 1.90 | † | 0.44 | 0.89 | NS | 0.46 | 0.80 | NS | 0.90 | 1.21 | NS |

| ΔVP-Pog (mm) | 2.40 | 2.32 | ∗ | −0.75 | 1.29 | NS | −0.62 | 1.02 | NS | −1.37 | 1.59 | ∗ |

| Dental | ||||||||||||

| ΔOB (mm) | 5.56 | 1.94 | ‡ | −0.99 | 1.05 | ∗ | −0.21 | 0.55 | NS | −1.20 | 1.44 | ∗ |

| ΔIMPA (°) | −0.66 | 7.34 | NS | 0.47 | 2.55 | NS | 0.08 | 2.05 | NS | 0.55 | 2.39 | ∗ |

| ΔU6-PP (mm) | −2.39 | 1.76 | † | 0.40 | 0.59 | NS | 0.05 | 0.35 | NS | 0.45 | 0.46 | ∗ |

| ΔU1-PP (mm) | 1.05 | 1.40 | ∗ | −0.07 | 0.49 | NS | 0.33 | 0.34 | ∗ | 0.27 | 0.49 | NS |

| ΔL1-MP (mm) | 1.59 | 2.10 | NS | −0.27 | 0.81 | NS | 0.22 | 0.58 | NS | −0.04 | 0.58 | NS |

| Variable 1 | Variable 2 | R | P | Sig (2-tailed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U6-PP | FMA | 0.56 | 0.120 | NS |

| U6-PP | OB | 0.02 | 0.963 | NS |

| OB | SNPog | 0.70 | 0.036 | ∗ |

| OB | SN-MP | −0.74 | 0.022 | ∗ |

| OB | SNB | 0.71 | 0.046 | ∗ |

| SNB | SNPog | 0.97 | 0.000 | ‡ |

| SNB | SN-MP | −0.79 | 0.011 | ∗ |

| VP-Pog | SNPog | 0.84 | 0.005 | † |

| VP-Pog | SN-MP | −0.50 | 0.175 | NS |

| VP-Pog | SNB | 0.83 | 0.006 | † |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses