Introduction

It is not known whether the design of the expander has an effect on initial adaptation, comfort level, speech, chewing, and swallowing, or whether age is a crucial aspect when dealing with speech adaptations. The objectives of this study were to assess whether patients of different age groups undergoing palatal expansion with various types of expanders experienced discomfort, speech impairment, chewing difficulty, and swallowing disturbances.

Methods

A questionnaire was developed and distributed to patients who had received palatal expanders in the preceding 3 to 12 months.

Results

Regardless of the type of expander, most patients initially felt oral discomfort, and had problems with speech and mastication. However, these disturbances were confined to the first week after cementation of the device. Remarkable adaptation to the device in all aspects studied was observed by the end of the first week. In addition, age did not influence the variables; younger patients and older teenagers responded similarly to the survey. In addition, the questionnaire responses did not appear to be related to the respondents’ sex.

Conclusions

Discomfort might not be a deciding variable when choosing an appliance. Instead, clinicians should base their decision on factors such as its biomechanics.

Most adolescents consider orthodontic treatment a right of passage and something that is socially desirable during this time in their life. However, along with the benefits of achieving a beautiful smile, orthodontic patients can experience many problems. For example, Stewart et al accurately stated that “orthodontic appliances must be interpreted as foreign bodies inserted in an important, and sensitive, area of the body.” Brackets and wires often cause pressure and ulceration of the mucosa; lingual appliances cause displacement of the tongue; palatal appliances cause a feeling of constraint; and fixed and removable devices interfere with speech, swallowing, and chewing, not to mention the generalized dental soreness and pain caused by local inflammation that ultimately results in tooth movement.

One might ask whether orthodontic patients fully understand what to expect. It is well known that clinical management is more efficient when all explanations are given, with anticipatory guidance provided before the appliances are placed. Moreover, information should be tailored to suit the type of treatment planned, should be accompanied by motivations, and should include a discussion of the effects of noncompliance.

In addition, few studies have monitored the long-term effects of orthodontic appliances on swallowing, comfort, and psychosocial aspects such as feelings of embarrassment. Generally, current evidence suggests that most negative effects of appliance wear become more tolerable with time, but most investigations in this field have focused on pain and speech.

Speech production can be affected by any osseous, muscular, dental, or soft-tissue deformity or any device impairing the movement or appearance of the speech sound articulators. For example, Johnson and Sandy evaluated malocclusion and abnormal tooth position in relation to articulation problems and concluded that, because of the potential for mechanism compensations and the ability of a motor act to adapt to changing landmarks, many patients achieve normal speech despite abnormal tooth position. Similarly, dental appliances might cause articulatory production errors of linguodental, labiodental, or linguoalveolar consonants, but these disruptions are minimized after a short period of wear because of functional adaptation.

The effects of orthodontic appliances on speech have been extensively studied during the past decades. Functional appliances have been rated the most deleterious to speech, followed by maxillary retainers, lingual fixed appliances, and lingual retainers. Usually, the impairment is temporary, varying from a few days to a few weeks; however, Stewart et al reported speech problems up to 3 months. Strutton and Burkland tested the effects of various designs of maxillary retainers on the clarity of speech at initial placement and concluded that Crozat type and modified horseshoe type retainers are superior to the traditional Hawley design.

With respect to speech problems, the most frequently affected sound is the /s/. In 1986, Laine studied palatal appliances and /s/ production and found that the narrower the palate, the greater the distortion of the /s/ sound because the appliance added a physical barrier to the palate and, therefore, diminished the tongue’s functional space. Haydar et al used audiotape recordings of 15 patients to evaluate speech on the first day of wearing the appliance, at 24 hours, and 1 week later. They concluded that, on the day of placement, there were statistically significant distortions of the /t,d/ and /k,g/ sounds with maxillary retainers, and the /t,n/, /k,g/, and /s,j/ sounds with maxillary and mandibular removable retainers. They found, at 24 hours of appliance wear, improvement of the /d/ and /k,g/ sounds with the maxillary retainer and of /t,n/ and /s/ with both retainers. At 1 week, they found that no significant sound problems remained. Hohoff et al evaluated speech and bonded lingual appliances. They concluded that these appliances caused speech problems, especially with the /s/ sound, and that smaller lingual appliances caused less-pronounced speech impairments.

Currently, there is little information about the effects of palatal expanders on speech and masticatory function, overall comfort of wear, chewing, and swallowing functions. Specifically, it is not known whether the design of the expander has an effect on initial adaptation, comfort level, speech, chewing, and swallowing, or whether age is a crucial aspect in speech adaptations. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to assess whether patients of different age groups undergoing palatal expansion with various types of expanders experienced discomfort, speech impairment, chewing difficulty, and swallowing disturbances.

In addition, our goal was to gather sufficient information to create future educational guidelines to help expedite patients’ adaptation to palatal expanders.

Material and methods

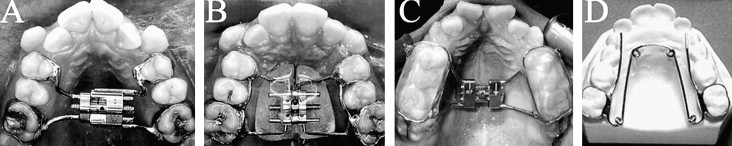

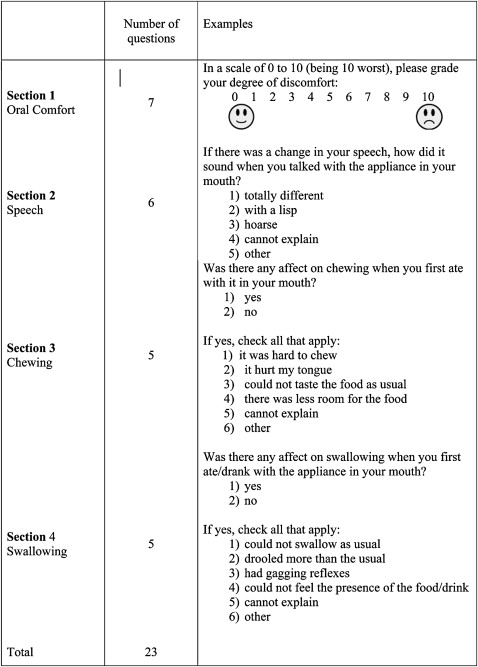

A questionnaire was developed, comprising 23 questions, to gather the data for this study. This questionnaire was distributed to patients who had received palatal expanders in the last 3 to 12 months from several private practices and an orthodontic graduate clinic. Of the 23 questions, 7 pertained to oral comfort (section 1), 6 to speech (section 2), 5 to chewing (section 3), and 5 to swallowing (section 4). The subjects’ responses were further categorized according to their appliances ( Fig 1 ).

The development of the questionnaire was based on previous published research. The study’s protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the University of Illinois at Chicago. Subject and parental consents were obtained. Instructions were given to the subjects, and all their questions were answered before administration of the questionnaire.

The subjects were asked to read the questionnaire items and circle the response that most closely agreed with how they experienced this item. The questions and responses, in a multiple-choice format, were kept to a minimum to ensure optimal compliance. Examples of the questions are shown in Figure 2 .

A total of 165 questionnaires were distributed and completed. Table I shows the demographics of the sample. Table II provides descriptive statistics for the sample. Cross-tabulation and appropriate statistical analysis with the Pearson chi-square test with the significance set at the 0.05 level were carried out.

| Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 60 | 41.1 |

| Female | 86 | 58.9 |

| Total | 146 | 100.0 |

| Age (y) | ||

| 7-10 | 24 | 18.2 |

| 11-14 | 77 | 58.3 |

| 15-18 | 28 | 21.2 |

| 19-22 | 3 | 2.3 |

| Total | 132 | 100.0 |

| Type of appliance | ||

| Hyrax | 12 | 8.6 |

| Haas | 50 | 36.0 |

| Bonded | 37 | 26.6 |

| Quad-helix | 32 | 23.0 |

| Did not know | 8 | 5.8 |

| Total | 139 | 100.0 |

| System not noted | 26 | |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses