Introduction

In this cross-sectional study, we investigated the impact of the orthosurgical treatment phases on the oral health–related and condition-specific quality of life (QoL) of patients with dentofacial deformities.

Methods

Two hundred fifty-four orthognathic patients were allocated into 4 groups according to treatment phase: initial (not yet treated), presurgical orthodontics, postsurgical orthodontics, and retention. Data were collected using the Oral Health Impact Profile to evaluate the oral health–related QoL, the Orthognathic QoL Questionnaire to analyze the condition-specific QoL, and the Index of Orthodontic Treatment Need to assess malocclusion severity and esthetic impairment. Specific malocclusion characteristics were also documented.

Results

A negative binomial regression analysis showed that the initial group had a more negative oral health–related QoL than did the postsurgical, presurgical, and retention groups (relative risks, 1, 0.79, 0.74 and 0.25, respectively). The initial group had a more negative condition-specific QoL than did the presurgical, postsurgical, and retention groups (relative risks, 1, 0.77, 0.38 and 0.15, respectively) regardless of age, income, or education; women reported greater negative impacts than men. Certain occlusal traits were related to higher Orthognathic QoL Questionnaire scores ( P <0.01).

Conclusions

Patients who completed their orthosurgical treatment had a significantly better oral health–related QoL and a more positive esthetic self-perception than did those undergoing treatment and those who were untreated. Crowding, crossbite, open bite, concave profile, edge-to-edge overjet, or Class III malocclusion negatively affected oral health–related QoL.

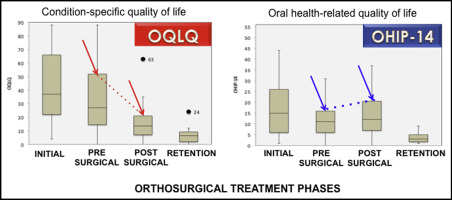

Graphical abstract

Highlights

- •

Oral health–related QoL and condition-specific QoL are diversely affected by orthosurgical treatment.

- •

The retention phase is more positive than the postsurgical, presurgical, and initial phases.

- •

Women had worse impacts related to a dentofacial deformity than did men.

- •

Presurgical patients showed less esthetic impairment than did untreated subjects.

- •

Some specific occlusal traits were related to higher OQLQ scores.

Dentofacial deformities are skeletal discrepancies associated with severe malocclusions that negatively affect esthetics, oral function, personality, and social behavior. Because the face is the primary source of personal identity, facial attractiveness influences personal and professional interactions throughout life. Facial features affect several personality ratings, including intelligence, friendliness, and popularity. Therefore, subjects with dentofacial deformities are at a disadvantage in society and may have low self-esteem, which negatively impacts mental health and quality of life (QoL).

Orthognathic surgery in conjunction with orthodontic treatment is the ideal management of dentofacial deformities. The traditional method involves the following phases: (1) initial, when the person seeks treatment and planning is performed; (2) presurgical orthodontics, when dental alignment and leveling are performed; (3) orthognathic surgery, when the jaws are repositioned to create a more harmonious facial skeleton; (4) postsurgical orthodontics, when the final occlusion is refined; and (5) retention, when the fixed appliances have been removed, and the health gain has been fully realized.

Because orthosurgical treatment dramatically affects appearance, function, and the psyche over a short period of time, it is crucial to analyze patient-centered outcomes, such as oral health–related QoL, in addition to the normative results observed by the involved professionals. Oral health–related QoL has been defined as “the absence of negative impacts of oral conditions on social life and a positive sense of dentofacial self-confidence.” In 2013, a systematic review indicated that patients had positive responses to orthognathic surgery, with significant improvements in QoL and psychological status. However, the review also reported significant variations in study designs and highlighted 3 standardized and validated questionnaires that have helped achieve consistent results: the Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36), the Oral Health Impact Profile-Short Form (OHIP-14), and the Orthognathic Quality of Life Questionnaire (OQLQ).

The SF-36 evaluates the impact of a condition on a subject’s perception of general health and has predominantly been used in medical studies to compare different populations. However, this generic questionnaire has limited use in dentistry because it is not sensitive to oral health changes and it has a limited ability to capture the effects of specific interventions.

The OHIP-14 assesses the impact of oral disorders and treatment modalities on oral health–related QoL regarding functional limitations; physical pain; psychological discomfort; physical, psychological, and social disabilities; and handicaps. This tool has been adopted by all dental specialties to capture the effects or side effects of interventions that could remain undetected by specific instruments.

Condition-specific instruments can evaluate clinically important health changes resulting from a health care intervention. The OQLQ was specifically developed to evaluate patients with dentofacial deformities according to their age, condition, and needs in 4 domains: oral function, facial esthetics, awareness of deformity, and social aspects of deformity. Although the OQLQ is the most precise and appropriate tool for assessing the impact of orthognathic surgery on condition-specific health-related QoL, only a few studies have reported its use (in the United Kingdom, Germany, China, Jordan, India, and Ireland ). Most of these studies evaluated small samples (14-65 subjects, except for Khadka et al, who included 110 Chinese orthosurgical patients), described the OQLQ translation and validation, focused on comparing the oral health–related QoL results from a few weeks before to short periods after orthognathic surgery, or evaluated only untreated subjects. Only 2 studies (from the United Kingdom and China ) used the OQLQ to evaluate patients at all treatment phases. Thus, there is a dearth of data on the perceived impact of orthosurgical treatment in larger cohorts across different cultures at all surgical-orthodontic treatment phases; a more thorough analysis of the distinct types of dentofacial deformities is also necessary.

In this cross-sectional study, we aimed to evaluate the changes in the oral health–related and condition-specific QoL of Brazilian patients with various dentofacial deformities at different orthosurgical treatment phases compared with untreated subjects. The influences of esthetic impairment, malocclusion severity, sociodemographic characteristics, and specific occlusal characteristics on oral health–related QoL were also examined.

Material and methods

An adequate sample size was calculated using the equation and effect-size indexes described by Cohen to enable a comparison of the quantitative data of the 4 groups having different interventions (4 treatment phases). It was estimated that a sample size of 45 patients in each group would be required to identify a medium-sized difference of 0.25: ie, a 25% reduction in the OQLQ and OHIP-14 scores at the 5% significance level, with a power of 80%.

The Brazil Platform Ethics Research Committee approved this study in September 2012. The participants were informed of the examination procedures and were assured of the confidentiality of the collected information and that it would not affect the treatment in any way. Only patients who signed a consent form were included in the study.

Subjects were recruited during routine appointments at 3 important public centers for surgical-orthodontic treatment from October 2012 to November 2013: the orthodontic clinic of the State University of Rio de Janeiro, the oral and maxillofacial surgery clinic of Pedro Ernesto University Hospital, and the craniomaxillofacial surgery department of the National Institute of Traumatology and Orthopedics. Patients who were totally edentulous or had clefts, syndromes, or a history of facial bone fractures were excluded.

The sample consisted of 254 consecutive patients (18-50 years old) with Angle Class I, Class II, or Class III malocclusions divided into 4 groups: (1) initial, untreated subjects with dentofacial deformities who had been referred for orthognathic surgery but had yet to undergo orthodontic bracket bonding; (2) presurgical orthodontics, patients undergoing dental alignment and leveling orthodontic treatment for orthognathic surgery planning with multibracket fixed appliances in both arches that began more than 6 months before the study; (3) postsurgical orthodontics, patients who had undergone orthognathic surgery more than 3 months before the study and were concluding orthodontic treatment with multibracket fixed appliances in both arches; and (4) retention, patients who had completed the surgical-orthodontic treatment and had their fixed orthodontic appliances removed more than 6 months before the study.

Data were collected by a trained orthodontic researcher (N.B.P.) in face-to-face interviews, with self-administered questionnaires completed in the clinic in the presence of the investigator, and also included oral examinations performed by a trained orthodontic researcher (N.B.P.). For the general and condition-specific oral health–related QoL assessments, all subjects were asked to complete the Brazilian versions of the OHIP-14 and the OQLQ, which have demonstrated psychometric properties similar to the original instruments.

All patients were instructed to answer the OHIP-14 questions based on their experiences regarding their teeth and mouth. The examiner (N.B.P.) asked them to complete the questionnaire by choosing 1 of the 5 options on the Likert scale (0, never; 1, hardly ever; 2, occasionally; 3, fairly often; 4, very often) for each item. Overall OHIP-14 scores range from 0 (no negative impact) to 56 (worst impact).

The OQLQ is rated on a 4-point scale with responses ranging from “it bothers you a little” (score 1) to “it bothers you a lot” (score 4), including the option “the statement does not apply to you or does not bother you at all” (score 0). The total OQLQ scores range from 0 (better QoL) to 88 (worse QoL). The 22 items analyze 4 dimensions: facial esthetics (items 1, 7, 10, 11, and 14), oral function (items 2-6), awareness of dentofacial esthetics (items 8, 9, 12, and 13), and social aspects of dentofacial deformity (items 15-22).

The interviews were performed before the clinical examinations, thus reducing the risk of buccal and occlusal conditions influencing the results. The examiner also recorded the treatment phase, age, sex, education, and socioeconomic status using the Brazilian Oral Health Survey of the Ministry of Health. This measurement categorizes the population according to family income.

All patients underwent a clinical malocclusion assessment with the Index of Orthodontic Treatment Need (IOTN). This indicator has 2 parts: the dental health component is a 5-grade index that records malocclusion severity, and the esthetic component assesses the esthetic impairment on a 10-point photographic scale, ranging from 1 (most attractive) to 10 (least attractive), as determined by the examiner (normative esthetic score) and the patient (self-perceived esthetic component score). These dental health component and esthetic component scores determine the need categories: no or little need (dental health component, 1 or 2; esthetic component, 1-4); borderline need (dental health component, 3; esthetic component, 5-7); and need or great need (dental health component, 4 or 5; esthetic component, 8-10).

A clinical assessment of the following specific malocclusion characteristics was also performed: facial profile (straight, concave, convex), molar and canine relationships (Angle Class I, Class II, Class III), incisor crowding (presence, absence), overbite (normal, 1-4 mm; deepbite, 5-8 mm; edge-to-edge, 0 mm; complete anterior overbite, ≥9 mm; open bite, <0 mm), overjet (normal, 1-3 mm; increased, ≥4 mm; edge-to-edge, 0 mm; negative, <0 mm), and crossbite (absence of crossbite, positive overjet with bilateral occlusal contact of posterior mandibular buccal segments to maxillary palatal cusps; posterior crossbite, positive overjet with occlusal contact of posterior mandibular lingual segments to maxillary buccal cusps on the left or right side; anterior crossbite, reverse overjet >1 mm with bilateral occlusal contact of posterior mandibular buccal segments to maxillary palatal cusps; complete crossbite, negative overjet with bilateral occlusal contact of posterior mandibular lingual segments to maxillary buccal cusps).

The dental evaluations were performed by an experienced orthodontist (N.B.P.) who was trained to measure dental parameters using the IOTN. An examiner calibration was performed by comparing the results from 20 plaster casts and photographs obtained by the examiner (N.B.P.) with those obtained by a gold-standard researcher (J.A.M.). A second examination was performed 10 days later to calculate intraexaminer reliability.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics and inferential analysis were used to characterize and compare the studied variables. Bivariate analyses between the treatment phases and the variables of interest were performed using the chi-square or Kruskal-Wallis test when appropriate. The independent effect of each surgical-orthodontic treatment phase on the oral health–related QoL was determined using multiple negative binomial regression models because there was evidence of data overdispersion (the likelihood ratio test for the dispersion parameter was P <0.01) and because of the nature of the primary outcome variable. Negative binomial models produce mean ratios when coefficients are exponentiated. Thus, the crude and adjusted mean ratios of the OHIP-14 and the OQLQ scores are presented for the 4 groups. The covariates included sex, age, education, and family income. The residuals of the models were assessed using R2 from the linktest function in Stata software (version 11.2; StataCorp, College Station, Tex). We also compared the crude model with the adjusted model for both outcomes.

Intraexaminer reliability and agreement between the examiner and the gold-standard researcher were estimated using the weighted kappa for the IOTN dental health and esthetic components scores before data collection. The Cronbach alpha was used to assess the internal consistency of the OHIP-14 and the OQLQ. This coefficient indicates whether the analyzed scale is homogeneous; values closer to 1 indicate greater internal consistency. All analyses were performed with the Stata software.

Results

The examiner was in excellent agreement with the gold-standard researcher for the IOTN dental health component with a kappa score of 0.96 (95% confidence interval [CI] lower limit, 0.90) and the IOTN esthetic component with a kappa score of 0.92 (95% CI lower limit, 0.86). The intraexaminer reliability was excellent for the IOTN dental health component at a weighted kappa score of 0.96 (95% CI lower limit, 0.92) and the IOTN esthetic component with a weighted kappa score of 0.98 (95% CI lower limit, 0.96), indicating consistency in the measurements.

The study sample included 254 adults (107 men, 147 women; mean age, 27.1 years) divided into 4 groups: initial (n = 65), presurgical orthodontics (n = 75), postsurgical orthodontics (n = 62), and retention (n = 52). No patients were excluded. The descriptive statistics indicated no significant differences among the 4 groups in terms of sex ( P = 0.46), education ( P = 0.28), or family income ( P = 0.10). There were statistically significant differences in age ( P <0.01) and the IOTN malocclusion assessment ( P <0.01) ( Table I ).

| Initial (n = 65) | Presurgical (n = 75) | Postsurgical (n = 62) | Retention (n = 52) | Total (n = 254) | P value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Sex | 0.463 ∗ | ||||||||||

| Female | 38 | 58.5 | 38 | 50.7 | 38 | 61.3 | 33 | 63.5 | 147 | 57.9 | |

| Male | 27 | 41.5 | 37 | 49.3 | 24 | 38.7 | 19 | 36.5 | 107 | 42.1 | |

| Age (y) | <0.001 † | ||||||||||

| Mean (±SD) | 26.6 (±8.3) | 24.8 (±6.8) | 27.9 (±8.1) | 30.1 (±8.8) | 27.1 (±9.2) | ||||||

| Schooling | 0.276 ∗ | ||||||||||

| Primary | 9 | 13.8 | 5 | 6.7 | 4 | 6.5 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 7.0 | |

| Secondary | 34 | 52.4 | 50 | 66.6 | 25 | 40.3 | 17 | 32.6 | 126 | 49.6 | |

| College | 20 | 30.8 | 19 | 25.4 | 25 | 40.3 | 23 | 44.3 | 87 | 34.2 | |

| Postgraduate | 2 | 3.0 | 1 | 1.3 | 8 | 12.9 | 12 | 23.1 | 23 | 9.2 | |

| Family income per month | 0.100 ∗ | ||||||||||

| <$680 | 27 | 41.5 | 28 | 37.4 | 19 | 30.6 | 14 | 26.9 | 88 | 34.6 | |

| $681-$1136 | 14 | 22.3 | 21 | 28.0 | 16 | 25.8 | 10 | 19.2 | 61 | 24.0 | |

| $1137-$2045 | 16 | 23.9 | 17 | 22.7 | 17 | 27.4 | 16 | 30.8 | 66 | 26.0 | |

| >$2046 | 8 | 12.3 | 9 | 11.9 | 10 | 16.2 | 12 | 23.1 | 39 | 15.4 | |

| IOTN-DHC | <0.001 ∗ | ||||||||||

| No/little need | 1 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 54 | 87.1 | 52 | 100 | 107 | 42.1 | |

| Borderline need | 8 | 12.3 | 5 | 6.7 | 1 | 1.6 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 5.5 | |

| Great need | 56 | 86.2 | 70 | 93.3 | 7 | 11.3 | 0 | 0 | 133 | 52.4 | |

| IOTN-AC self-perceived | <0.001 ∗ | ||||||||||

| No/little need | 28 | 43.1 | 58 | 77.3 | 62 | 100 | 52 | 100 | 200 | 78.7 | |

| Borderline need | 23 | 35.4 | 11 | 14.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 34 | 13.4 | |

| Great need | 14 | 21.5 | 6 | 8.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 7.9 | |

| IOTN-AC normative | <0.001 ∗ | ||||||||||

| No/little need | 3 | 4.6 | 0 | 0 | 61 | 98.4 | 52 | 100 | 116 | 45.7 | |

| Borderline need | 15 | 23.1 | 11 | 14.7 | 1 | 1.6 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 10.6 | |

| Great need | 47 | 72.3 | 64 | 85.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 111 | 43.7 | |

Most subjects in the initial and presurgical groups had a great need for treatment as determined by the IOTN dental health component and the normative IOTN esthetic component. However, based on the self-perceived IOTN esthetic component, only a few in those groups considered themselves in great need (initial, 21%; presurgical, 8%). Most respondents in the presurgical group considered themselves having little need (77.3%), with only minor esthetic impairment. Most patients in the postsurgical and retention groups had little need based on the IOTN dental health component and minor esthetic impairment assessed by both the normative and the self-perceived IOTN esthetic component. These data demonstrated the positive impact of surgical-orthodontic therapy on the esthetic judgment of patients who were undergoing or had already completed the treatment ( Table I ).

The most prevalent malocclusion-specific traits in the initial and presurgical groups were Angle Class III malocclusion, concave profile, crossbite, negative overjet, and open bite. Crowding in both arches was prevalent only in the initial group. Most subjects in the postsurgical and retention groups displayed Angle Class I, a straight profile, no crossbite and crowding, and normal overjet and overbite ( Table II ).

| Initial | Presurgical | Postsurgical | Retention | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Total | 65 | 100 | 75 | 100 | 62 | 100 | 52 | 100 |

| Profile | ||||||||

| Straight | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 57 | 92.0 | 50 | 96.2 |

| Convex | 22 | 33.8 | 23 | 30.7 | 5 | 8.0 | 2 | 3.8 |

| Concave | 43 | 66.2 | 52 | 69.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Molar relationship | ||||||||

| Class I | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2.7 | 62 | 100 | 50 | 96.2 |

| Class II | 23 | 35.4 | 19 | 25.3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3.8 |

| Class III | 42 | 64.6 | 54 | 72.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Canine relationship | ||||||||

| Class I | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2.7 | 61 | 98.4 | 52 | 100 |

| Class II | 22 | 33.85 | 19 | 25.3 | 1 | 1.6 | 0 | 0 |

| Class III | 43 | 66.15 | 54 | 72.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Crowding, maxillary arch | ||||||||

| Absence | 11 | 16.9 | 63 | 84.0 | 62 | 0 | 48 | 92.3 |

| Presence | 54 | 83.1 | 12 | 16.0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 7.7 |

| Crowding, mandibular arch | ||||||||

| Absence | 8 | 12.3 | 63 | 84.0 | 61 | 98.4 | 48 | 92.3 |

| Presence | 57 | 87.7 | 12 | 16.0 | 1 | 1.6 | 4 | 7.7 |

| Crossbite | ||||||||

| Absence | 28 | 43.1 | 22 | 29.3 | 60 | 96.8 | 52 | 100.0 |

| Posterior | 10 | 15.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anterior | 9 | 13.9 | 18 | 24.0 | 2 | 3.2 | 0 | 0 |

| Complete | 18 | 27.6 | 35 | 46.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Overbite | ||||||||

| Normal | 18 | 27.7 | 19 | 25.3 | 61 | 98.4 | 52 | 100.0 |

| Edge-to-edge | 13 | 20.0 | 21 | 28.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Deepbite | 2 | 3.1 | 2 | 2.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Complete | 5 | 7.7 | 3 | 4.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Open bite | 27 | 41.5 | 30 | 40.0 | 1 | 1.6 | 0 | 0 |

| Overjet | ||||||||

| Normal | 8 | 12.2 | 8 | 10.7 | 58 | 93.6 | 42 | 80.8 |

| Increased | 23 | 35.4 | 20 | 26.7 | 4 | 6.4 | 10 | 19.2 |

| Edge-to-edge | 9 | 13.9 | 3 | 4.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Negative | 25 | 38.5 | 44 | 58.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The OHIP-14 instrument had a Cronbach alpha of 0.90 (95% CI lower limit, 0.88), indicating good internal consistency. The OQLQ had excellent internal consistency, with a Cronbach alpha of 0.96 (95% CI lower limit, 0.95). The 4 OQLQ domains also demonstrated good internal consistency: social aspects of the deformity with a Cronbach alpha of 0.94 (95% CI lower limit, 0.93); oral function with a Cronbach alpha of 0.88 (95% CI lower limit, 0.86); facial esthetics with a Cronbach alpha of 0.91 (95% CI lower limit, 0.89); and awareness of deformity with a Cronbach alpha of 0.83 (95% CI lower limit, 0.79).

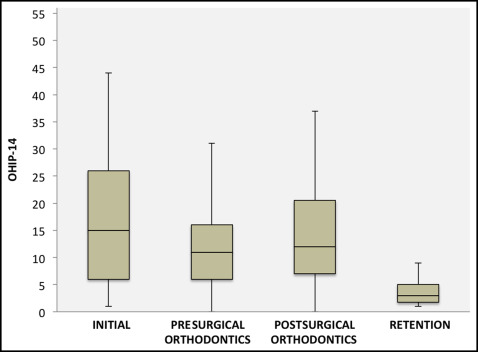

The OHIP-14 scores indicated that subjects in the initial group experienced the most negative impacts on general oral health, followed by those in the postsurgical, presurgical, and retention groups ( Fig 1 ; Table III ). The total OQLQ scores showed that the initial group had the worst impacts specific to the dentofacial deformity, followed by the presurgical, postsurgical, and retention groups ( Fig 2 ; Table III ). Three OQLQ domains (facial esthetics, oral function, and social aspects of dentofacial deformity) followed this same pattern; however, awareness of the deformity showed the same pattern as did the OHIP-14 data ( Table III ).

| Group | OHIP-14 total | OQLQ total | OQLQ facial | OQLQ function | OQLQ awareness | OQLQ social |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 16.9 ± 12.2 | 43.5 ± 24.2 | 11.5 ± 6.7 | 8.5 ± 6.3 | 7.9 ± 4.9 | 15.6 ± 10.4 |

| Minimum | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Median | 5 | 37 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 14 |

| Maximum | 44 | 88 | 20 | 20 | 16 | 32 |

| Presurgical | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 13.3 ± 10.5 | 33.3 ± 23.0 | 9.3 ± 6.6 | 7.5 ± 6.2 | 6.3 ± 4.8 | 10.2 ± 10.0 |

| Minimum | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Median | 11 | 27 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 8 |

| Maximum | 48 | 88 | 20 | 20 | 16 | 32 |

| Postsurgical | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 14.4 ± 11.4 | 15.4 ± 10.7 | 3.3 ± 3.6 | 4.7 ± 4.4 | 4.2 ± 3.9 | 3.1 ± 3.7 |

| Minimum | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Median | 12 | 13.5 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| Maximum | 56 | 63 | 19 | 19 | 16 | 15 |

| Retention | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 4.4 ± 4.2 | 6.2 ± 4.7 | 0.9 ± 1.2 | 1.9 ± 2.4 | 1.7 ± 1.5 | 1.7 ± 2.1 |

| Minimum | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Median | 3 | 6.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 1 |

| Maximum | 18 | 24 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 8 |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses