Despite a vast body of supportive scientific literature reaching back into the 19th century, surgical treatment of patients with temporomandibular joint disease remains controversial in the early 21st century, perhaps in part because relatively few surgeons (or patient advocates) have examined the rich history of these operations. Certainly, reading about the history of temporomandibular joint surgery enhances our understanding of the principles behind contemporary surgical therapy. Yet, as we read the unfamiliar and dated language of individuals whose names may sometimes be known but whose faces most often have faded from human memory, the mists of time lift slightly and we catch glimpses of what it meant to be a surgeon 50, 80, or 100 years ago. Although this chapter can only briefly summarize the accomplishments (and failures) whose legacy is our contemporary knowledge and practice, it will fulfill its purpose if the reader is inspired to visit some of the pioneering articles themselves, seeing them in their original context among papers describing advances in general, orthopedic, or plastic surgery, and in more recent decades encased by advertisements for the latest and best materials, pharmaceuticals, and instruments, most of which are now long forgotten.

In fact, it is often difficult for the contemporary reader to examine outdated techniques and concepts without an anachronistic and even arrogant sense of omniscience. To understand the significance of our surgical forefathers’ accomplishments, we must abandon our comparatively vast understanding of human physiology, inflammation, pain, and healing, not to mention our sophisticated technology, instrumentation, imaging capabilities, and pharmaceutical armamentarium. Imagine instead devising an approach to a temporomandibular joint that you have not imaged and whose normal structure and function are largely matters of speculation. Then, perform your operation on a patient anesthetized with an open cloth soaked in ether or chloroform—the latest textbooks discuss the comparative risks and benefits of these two anesthetic gases; both are known to have major safety and efficacy risks to patient and surgical team alike. Finally, hope that any infection afterward does not prove to be fatal, and that the operation leaves the patient better off, not worse.

PIONEERS

Numerous advances notwithstanding, most fundamental surgical procedures employed in the treatment of temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disease have been known, practiced, and described in the surgical literature for a century or longer. Thomas Annandale generally is credited with the first published description of temporomandibular joint disc repair in 1887 ( Figure 41-1 ).

He describes successfully treating two patients with locking or painfully clicking TMJs using surgical disc repositioning, having correctly hypothesized that the problems lie with the “inter-articular” cartilage of the TMJ displaced “either from a sudden tearing of their connections or from a gradual stretching of them.” The contemporary wisdom of the time was represented by a textbook that he quoted, which describes the disorder as “an affection occurring principally in delicate women…. thought to depend upon relaxation of the ligaments of the joint permitting too free a movement…. and possibly a slipping of the inter-articular cartilage.” This opinion may sound eerily familiar to the contemporary reader, but other 19th century concepts are now unthinkable: Annandale’s second patient was kept in hospital 10 days before her surgery and 13 days after.

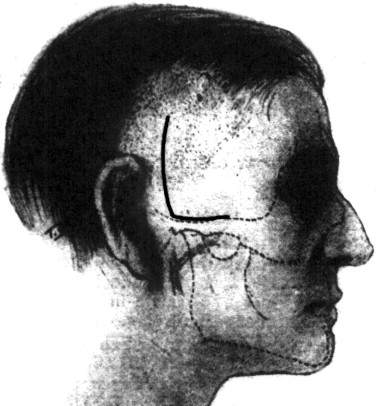

Treating the temporomandibular joint was by no means a standard operation in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Annandale used a small incision comparable with a modern conservative preauricular approach. In contrast, the 1895 edition of Stimson’s Manual of Operative Surgery describes excision of the mandibular condyle through a T-shaped incision with its horizontal arm along the inferior aspect of the zygoma about 1¼ inches in length and the vertical arm, through skin only, about 1 inch long. The “parotid, nerves and vessels” were retracted inferiorly to prevent injury. In 1914, John Murphy of Chicago produced a detailed report on nine cases of TMJ ankylosis treated by arthroplasty with rotation of an interpositional flap of temporal fat and temporalis fascia. His incision was L-shaped, with its base along the superior aspect of the zygomatic arch and a vertical arm at the posterior end, extending upward 1½ inches ( Figure 41-2 ).

Murphy claimed that keeping the horizontal incision above the zygomatic arch avoided branches of the facial nerve. Behan published a detailed and well-illustrated description of TMJ arthrotomy in 1918, returning to the vertical preauricular approach. In the same year, John Blake in Boston noted the difficulties of approaching the TMJ: “It is hard to reach for the purpose of careful detailed attack, as it lies deep below the surface, and is surrounded by good-sized arteries and nerves; a clear dry field is hard to obtain, and accurate work on the joint is consequently far from easy.” Even so, others pressed on: In Philadelphia, Ashhurst called Blake’s concerns “undue emphasis” and reached the joint through an inverted L-shaped incision, following the zygomatic arch horizontally for 2 cm, then turning inferiorly from the posterior end for 3 cm.

These early TMJ surgeons and several others in the United States, Great Britain, and Europe were pioneers in devising approaches to the TMJ and procedures to restore the joint to better function. According to contemporary standards, their incision designs range from unsophisticated to dangerous and disfiguring, but these men were hardly unsophisticated themselves. All were exceptional anatomists and broadly trained surgeons who critically reassessed the little TMJ pathophysiology known to them, brought fresh thinking to their patients’ problems, and applied principles gained from experience in other operations and diseases to the TMJ in novel and perceptive ways. They were certainly aware of one another’s work: Most cited one another, and nearly all referenced Annandale’s article from a quarter-century before, as well as still earlier compilations of jaw dysfunction cases that offered insight into the TMJ symptoms they faced, if little of use on surgical therapy.

EARLY ARTHROPLASTY

THE SNAPPING JAW

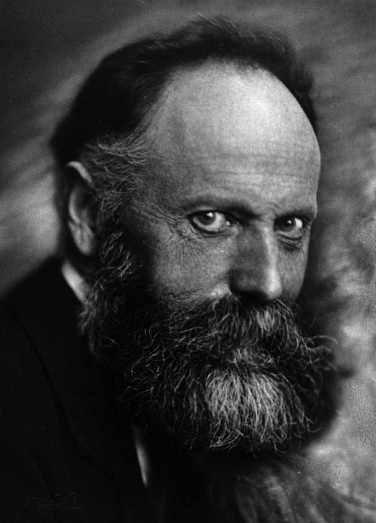

By the 1920s, a reasonable body of literature and clinical experience had accumulated regarding TMJ anatomy and function, and several distinct joint pathologies now possessed documented surgical remedies. Annandale had treated painful locking and clicking joints with disc repositioning 30 years earlier, but for many years, little more was published on surgery for this particular condition. In 1918, Behan described finding either anterior or posterior disc attachments torn and repaired them to reposition the disc. That same year, Pringle hypothesized that the lateral pterygoid muscle could displace the articular disc anteriorly and medially, and treated the condition with what he believed to be the first excision of the disc. Ashhurst duplicated this operation successfully in 1921 on a 16-year-old female patient. Unknown to both of them, the Swiss surgeon Otto Lanz ( Figure 41-3 ), professor of surgery in Amsterdam, had published two cases of TMJ discectomy on an 18-year-old and a 24-year-old woman that he had performed in 1906 and 1908. Lanz, who also invented the mesh skin graft during this time, had reported his surgeries a decade earlier in the German-language journal Zentralblatt für Chirurgie .

It was Ashhurst, however, who resurrected a term first used nearly a century earlier by Cooper and christened the internally deranged TMJ the “snapping jaw,” a term applied for the next several decades to a rather vaguely defined painful popping or snapping jaw that might intermittently become stuck open, closed, or something in between.

In fact, confusion reigned regarding the actual location and movement of the articular disc in normal function, not to mention its role in the intermittently locking, subluxing, dislocating, and/or snapping joint. Early on, Cooper had compared the subluxing TMJ to injured knees and hypothesized that capsular ligamentous laxity allowed subluxation, although he also believed that the disc could become displaced behind the mandibular condyle and thus prevent full mandibular closure. The debate on whether capsular laxity or disc displacement was responsible for the observed symptoms continued for a century and longer. Despite multiple reports of encountering the disc displaced anteriorly at surgery and repositioning it posteriorly, some authors persisted in blaming a posteriorly displaced disc or a loose lateral capsule for the pain and snapping noises in the TMJ. Some confusion may stem from inconsistent use of terminology: Many case reports were unclear on precisely what jaw mobility dysfunction was present, and the term subluxation seems to have been applied sometimes to the jaw and sometimes to the disc (without specifying whether the disc was thought to be malpositioned anteriorly or posteriorly). Contemporary understanding of anterior disc displacement and reduction is relatively recent, and perhaps the early confusion is understandable. If one considers the broadly diverse treatments available today for chronic subluxation/dislocation, it can be seen that we may have not progressed all that far in our understanding of this condition.

Although Lanz, Ashhurst, and Pringle directed surgery at the disc, others attempted to control “subluxation” through extracapsular procedures. Blake successfully prevented recurrent dislocation in an adult male patient by wiring the coronoid process to the zygomatic arch to restrict mandibular opening. And in Germany, Nieden improved on safe access to the TMJ and devised a new procedure to restrict condylar movement. He elevated an inferiorly based flap of temporalis fascia, rotated it inferiorly, and secured the free end to the lateral joint capsule to tighten it and restrict condylar movement. Several years later, this surgery was declared to be “based upon the soundest surgical principles” for treating hypermobility, and the loose lateral capsule was believed to be the main point of origin for several more decades. The story of Professor Doctor Nieden would not be complete, however, without taking note of a darker side. A highly decorated military surgeon during World War I, Nieden chose a less than noble course during the National Socialist years. He joined the Nazi party early, worked with the Gestapo before and during World War II, and served in the SS: Published accounts name him as a surgeon who performed compulsory sterilization on mixed race children in the 1930s.

ANKYLOSIS

Painful snapping was not the only TMJ pathology treated by operation, nor the most common. Ankylosis was perhaps the earliest TMJ condition treated surgically, although most 19th century surgeons in Europe attempted to solve the problem with osteotomies away from the TMJ itself. In the United States, Murphy reported on nine patients with TMJ ankylosis whom he treated during the years leading up to 1914. His paper is a grim reminder of the fearsome complications caused by infection in the pre-antibiotic era. Table 41-1 lists the ages of onset and causes of ankylosis for his case series.

| Case # | Onset Age | Cause |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 mo | Otitis media, mastoiditis |

| 2 | 6 yr | Kicked in jaw by horse, angle fracture with infection |

| 3 | Birth? | Difficult delivery, facial deformity noted early in life |

| 4 | 9 yr | Fall from third story, chin impact, immediate trismus |

| 5 | Birth | Unknown |

| 6 | 2½ yr | Severe mastoiditis, otitis, recurrent abscesses for over 6 months |

| 7 | 14 | Fall from horse without direct facial injury; progressive hip, spine, and jaw immobility |

| 8 | 2½ yr | Throat infection, subsequent generalized abscesses |

| 9 | 17 | Sepsis, osteomyelitis |

Although some cases appear to represent congenital deformities or sequelae of direct trauma, a significant number of his ankyloses appear to be late effects of local (especially mastoiditis) or widely disseminated infection, leading to septic arthritis of the TMJ, a condition very rarely seen today. His treatment consisted of freeing the ankylosis by removing the bone in the area of the condyle and rotating a fascia and a fat flap from the temple into the gap, then propping the patient’s mouth open for 2 weeks with a wedge-shaped wooden block. His purpose for this was to “prevent possible compression necrosis of the interposing flap.” He reported good mandibular movement at follow-up periods of 4 to 11 months, with one recurrent ankylosis.

THE ROLE OF DENTAL OCCLUSION

During the early 20th century, intrinsic pathology of the TMJ was addressed with little apparent consideration for the state of the patient’s dental occlusion. Orthopedic principles derived from greater experience in other joints were applied to the TMJ, with results reportedly satisfactory to patient and surgeon alike. By 1930, John Morris was able to present a thorough and insightful review of the state of the art in treating the snapping jaw. He perpetuated the assertion that capsular laxity with consequent excessive condylar movement was responsible for the observed snapping, pain, and hypomobility. However, he recognized that posterior disc displacement was anatomically unlikely and therefore an unacceptable cause. Building on the work of Pringle, he postulated that anterior displacement ultimately led to secondary joint laxity, which, in turn, produced symptoms. More significantly, he summarized the contemporary treatments available for the snapping jaw ( Box 41-1 ) and argued convincingly that joint surgery offered the best solution.

- I.

Non-operative methods

- A.

Dental technical procedures

- 1.

Outside mouth

- (a)

Apparatus, fastened around chin and held in position by cap on head; limits chewing motion and depression of point of jaw

- (a)

- 2.

Inside mouth

- (a)

Splint, fastened to upper and lower jaw with intervening catch hinge, is adjustable to limit motion of lower jaw (Schroeder).

- (b)

Hard rubber plate, fixed to upper jaw and provided with process pointing of edge of masseter muscle or coronoid process, limits excursion of latter (Fritzsche).

- (a)

- 1.

- B.

Injection of corrosive fluids into joint (to produce shrinkage of capsule and promote adhesions)

- 1.

Tincture of iodine (¾ cubic centimeter tincture of iodine injected into joint posteriorly secured permanent cure in case of girl, aged 20 years, as reported by Perthes)

- 2.

Alcohol

- 1.

- A.

- II.

Operative method

- A.

Treatment of capsule

- 1.

Excision of portion of capsule is followed by suture to overcome redundancy (Perthes).

- 2.

Simple plication of capsule after exploration of joint takes up redundancy and tightens joint.

- 1.

- B.

Use of fascial strip (turned down from temporal region to check excursion of head, as described by Nieden)

- C.

Treatment of meniscus

- 1.

Fixation of disc by suture to periosteum of mandibular fossa (Haeber)

- 2.

Fixation of disc in vertical position in front of condylar process (Konjetzny)

- 3.

Removal of the articular disc (Ashhurst)

- 1.

- A.

Morris’s writings reflect progress made since the time of Annandale nearly half a century earlier, not only with respect to the TMJ but for all of orthopedic surgery. He decries that “standard surgical texts limit operative indications to such conditions as ankylosis, arthritis, irreducible dislocations, and a few unusual fractures. Subluxation of the joint as a surgical consideration is either dismissed as of no importance, or its existence is completely ignored.” He responds by asserting that “operative indications, which were formerly limited to the more grave pathological conditions, have been gradually extended to include a variety of derangements the minor character of which did not justify the hazards imposed by the older methods. The acceptance of the minor joint lesions for radical surgical treatment indicates the highest degree of confidence in the safety and efficiency of the methods employed and offers as well the most convincing evidence of the advances made in this field.”

However, within a few years, the philosophy undergirding temporomandibular joint care would turn in the opposite direction. Washington University otolaryngologist James Costen studied a large cohort of patients with varying combinations of headache, ear pain, neuralgia, glossodynia, and other less common complaints associated with abnormal jaw movement and malocclusion. He theorized that loss of posterior occlusal support (a common phenomenon of the time) led to excessive pressure on the TMJ with subsequent destruction, dysfunction, and nerve compression. His theory was ultimately published in the Journal of the American Medical Association and gained widespread acceptance for nearly two decades; the “snapping jaw” became “Costen’s syndrome.”

Treatment of patients with this new syndrome, whose symptoms were correctly observed to be much more common than was previously recognized, was dental. The posterior occlusion was gradually opened; this was believed to decompress the nerves and other tissues within the TMJ and to allow healing. Most patients improved; those who did not were sometimes assumed by their treating physicians to have received poor care from their dentists. In fact, Costen even advocated against removing the molar teeth in any patient with a head and neck neuralgia.

Although surgery for TMJ internal derangements did continue to be practiced, Costen’s syndrome validated and energized an entire school of thought that attributed joint pathology to occlusal disharmonies. In fact, therapy following Costen’s principles and the many subsequent dental refinements was reasonably effective, although probably not for the reasons believed. However, as early as 1940, some authors questioned the anatomic basis of Costen’s neurologic symptoms. Dingman concludes a thorough review of TMJ therapy by warning, “We must not lose sight of the fact that many of the statements made regarding this subject [Costen’s syndrome] are still within the realm of speculation and need further scientific investigation for substantiation…. By assuming a critical attitude and proceeding in a cautious manner, the dental profession may avert severe criticism that might arise as a result of misguided therapy.” His advice remains wise today.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses