A summary of the current status of modification of jaw growth indicates the following. 1. Transverse expansion of the maxilla is easy before adolescence, requires heavy forces to create microfractures during adolescence, and can be accomplished only with partial or complete surgical osteotomy after adolescence. Transverse expansion of the mandible or constriction of either jaw requires surgery. 2. Acceleration of mandibular growth in preadolescent or adolescent patients can be achieved, but slower than normal growth afterward reduces or eliminates a long-term increase in size of the mandible. Restraint of maxillary growth occurs with all types of appliances to correct skeletal Class II problems. For short-face Class II patients, increasing the face height during preadolescent or adolescent orthodontic treatment is possible, but it may make the Class II problem worse unless favorable anteroposterior growth occurs. For those with a long face, controlling excessive vertical growth during adolescence is rarely successful. 3. Attempts to restrain mandibular growth in Class III patients with external forces largely result in downward and backward rotation of the mandible. Moving the maxilla forward with external force is possible before adolescence; moving it forward and simultaneously restricting forward mandibular growth without rotating the jaw is possible during adolescence with intermaxillary traction to bone anchors. The amount of skeletal change with this therapy often extends to the midface, and the short-term effects on both jaws are greater than with previous approaches, but individual variations in the amount of maxillary vs mandibular response occur, and it still is not possible to accurately predict the outcome for a patient. For all types of growth modification, 3-dimensional imaging to distinguish skeletal changes and better biomarkers or genetic identification of patient types to indicate likely treatment responses are needed.

Highlights

- •

Many have attempted to change proportional relationships during skeletal growth.

- •

Successful treatment would limit unwanted dental compensations.

- •

Changes of a few millimeters have been possible in growing Class III patients.

- •

Miniplate anchorage combined with light forces has produced promising results.

- •

Biomarkers are needed to predict outcomes and define indications for use.

Although growth modification has been considered important from the beginning of orthodontics, the concepts underlying its use and the views of its clinical usefulness have varied greatly over time. To orthodontists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, growth modification was easy because it was assumed that growth was largely controlled by environmental factors and was judged as successful because the dental occlusion improved. By midcentury, cephalometrics had shown that most of the changes produced by the treatment methods of that time were tooth movement, not modified growth. At that point, the American view was that it was almost impossible to modify growth because of tight genetic control, and that attempts to do so were rarely indicated. Europeans remained more positive; in the United States, there was increasing acceptance of European functional appliances and enthusiasm for growth modification in the last quarter of the century. There is a somewhat less enthusiastic view of it now, as better data for long-term outcomes have become available, and genetic influences once again are being emphasized.

In this article, we had 2 goals: (1) to provide an overview of growth modification possibilities and limitations based on the best current data for the various types of malocclusions, and (2) to discuss in more detail Class III growth modification with elastics to bone anchors, the most recent form of growth modification and, in terms of short-term changes, perhaps the most successful.

Transverse growth modification

Transverse growth modification is largely done in the context of maxillary expansion by opening the midpalatal suture. Ample clinical evidence now confirms that opening the suture can be accomplished. In young children, up to age 8 or 9 years, little force is needed. Up to that age, a transpalatal lingual arch for dental expansion also will open the midpalatal suture. A jackscrew device is not needed, and rapid expansion is contraindicated because of the possibility of injury to the nose, involving displacement of the vomer bone.

By age 9 or 10, there is enough interdigitation of bone spicules on the edges of the midpalatal suture that opening the suture requires microfractures, and a heavier force from a jackscrew device is necessary to do this. The rate of opening the suture with a jackscrew remains controversial. The original reason for rapid expansion was that the suture would open too rapidly for tooth movement to accompany it, and the amount of skeletal vs dental change would be greater. This is true in the short term but not in the medium or long term: after rapid expansion, skeletal relapse is followed by tooth movement, so that a few weeks after the jackscrew is tied off and left in place as a retainer, the skeletal and dental components of the expansion are about 50-50. Approximately the same ratio is found when the expansion is done slowly, at a rate of about 1 mm per week. Slow expansion, therefore, can be considered an equally effective and less traumatic way to expand the maxilla. Additional transverse growth after adolescent expansion almost never occurs.

The suture opens in a “V” pattern both transversely and vertically, with more expansion anteriorly and some expansion all the way up to the orbits. Extremely heavy force in late adolescence carries with it the risk of an uncontrolled fracture that extends vertically and can lead to a significant injury.

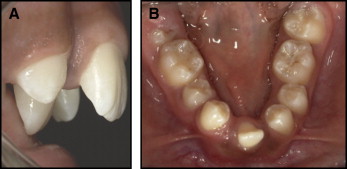

Transverse expansion of the mandible is possible only with distraction osteogenesis at the symphysis. The major indication is lack of development of the mandibular midline structures ( Fig 1 ). Symphysis distraction as a way to gain space for the alignment of crowded mandibular incisors is now judged to have a poor ratio of benefit to cost and risk.

Excessive transverse growth is almost totally a problem in the mandible. Mandibular arch width is affected by tongue size and posture; with a large tongue carried low in the mouth, a posterior crossbite is likely to be present with normal or even wide maxillary dimensions. It may be the best clinical judgment to tolerate such a crossbite rather than to attempt an extreme maxillary expansion. Narrowing the mandibular arch in such a case is almost impossible; surgical narrowing by removal of bone at the symphysis is difficult and potentially unstable.

Modifying Class II growth

Patients with a Class II growth pattern have some combination of deficient forward mandibular growth and excessive maxillary growth that is more likely to be downward than forward. The desired growth modification, of course, is stimulation of forward mandibular growth and restraint of maxillary growth in both directions.

The orthodontic literature has hundreds of reports of devices to modify growth in this way and much data for outcomes of treatments. Functional appliances that position the mandible forward are the mainstays of treatment. Their short-term effects are summarized in a recent meta-analysis, to which readers are referred for further information. The conclusions relative to growth modification are that (1) functional appliances can accelerate the rate of forward mandibular growth before and during adolescence, (2) there is an element of restraint of maxillary growth in the response, and (3) a significant part of the correction of a Class II malocclusion is due to dental rather than skeletal change.

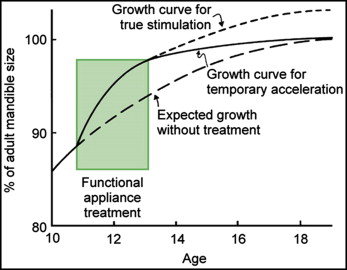

Does acceleration of mandibular growth during adolescence lead to a larger mandible at the end of the growth period? The possibilities are shown in Figure 2 ; the consistent conclusion is that the period of growth acceleration is followed by diminished growth later, so that if there is any increase in mandibular length in the long term, it is quite small. Sometimes the change is evaluated as statistically significant; sometimes it is not, but the data do not support the idea that the orthodontist is “growing mandibles.”

Is extraoral force to the maxilla effective in restraining its forward growth? The answer is yes, and the amount of growth restraint is greater with headgear than with functional appliances, but the outcomes of treatment between functional appliances and headgear are remarkably similar. It appears that an improvement in the anteroposterior position of the maxilla relative to the mandible greater than 5 mm is about as much as growth modification can provide, and that such a favorable result occurs in not more than two thirds to three quarters of the patients treated during adolescence.

The timing of Class II growth modification treatment remains controversial despite multiple clinical trials with the same conclusion: that 2-stage treatment beginning before the adolescent growth spurt is not more effective than 1-stage treatment during adolescence. The primary indication for preadolescent treatment, therefore, is psychosocial problems caused by teasing and harassment about protruding maxillary teeth, not a severe malocclusion.

Modifying Class II growth

Patients with a Class II growth pattern have some combination of deficient forward mandibular growth and excessive maxillary growth that is more likely to be downward than forward. The desired growth modification, of course, is stimulation of forward mandibular growth and restraint of maxillary growth in both directions.

The orthodontic literature has hundreds of reports of devices to modify growth in this way and much data for outcomes of treatments. Functional appliances that position the mandible forward are the mainstays of treatment. Their short-term effects are summarized in a recent meta-analysis, to which readers are referred for further information. The conclusions relative to growth modification are that (1) functional appliances can accelerate the rate of forward mandibular growth before and during adolescence, (2) there is an element of restraint of maxillary growth in the response, and (3) a significant part of the correction of a Class II malocclusion is due to dental rather than skeletal change.

Does acceleration of mandibular growth during adolescence lead to a larger mandible at the end of the growth period? The possibilities are shown in Figure 2 ; the consistent conclusion is that the period of growth acceleration is followed by diminished growth later, so that if there is any increase in mandibular length in the long term, it is quite small. Sometimes the change is evaluated as statistically significant; sometimes it is not, but the data do not support the idea that the orthodontist is “growing mandibles.”

Is extraoral force to the maxilla effective in restraining its forward growth? The answer is yes, and the amount of growth restraint is greater with headgear than with functional appliances, but the outcomes of treatment between functional appliances and headgear are remarkably similar. It appears that an improvement in the anteroposterior position of the maxilla relative to the mandible greater than 5 mm is about as much as growth modification can provide, and that such a favorable result occurs in not more than two thirds to three quarters of the patients treated during adolescence.

The timing of Class II growth modification treatment remains controversial despite multiple clinical trials with the same conclusion: that 2-stage treatment beginning before the adolescent growth spurt is not more effective than 1-stage treatment during adolescence. The primary indication for preadolescent treatment, therefore, is psychosocial problems caused by teasing and harassment about protruding maxillary teeth, not a severe malocclusion.

Short-face and long-face growth modification

Vertical deviations from acceptable facial proportions are less frequent but not less important than anteroposterior deviations and can accompany Class II or Class III growth patterns.

The best description of short-face problems is that the lower third of the face is short relative to the other facial thirds; the graphic way to say it is that the chin is too close to the nose. Patients with this problem usually have a relatively long ramus, an acute gonial angle, and a low mandibular plane angle: the so-called skeletal deepbite configuration. If they also are somewhat mandibular deficient, a Class II Division 2 malocclusion may be present.

In those patients, one would want downward growth of the mandible and would be willing to accept some downward rotation of the mandible to increase anterior face height. The problem is that rotating the mandible down also moves the chin back, so improving the face height may make the mandibular deficiency worse.

The most successful approach to growth modification in these patients is an activator or bionator type of appliance, with contact of the mandibular incisors against the palatal portion of the appliance and the acrylic trimmed to allow eruption of the mandibular posterior teeth. It may be necessary to tip the maxillary incisors facially first to allow mandibular advancement. A less desirable alternative is cervical headgear because it elongates the maxillary posterior teeth and rotates the occlusal plane down posteriorly. It is better to increase both the occlusal plane and the mandibular plane angles during treatment.

Does the deepbite impede forward mandibular growth? Occasionally, there is a burst of forward growth as face height is increased, but this is the exception rather than the rule. On the other hand, lengthening the face is a quite successful form of growth modification. For Class II deepbite patients, trauma to the palatal soft tissues or gingivae facial to the mandibular incisors is an indication for beginning treatment before adolescence.

In contrast, modifying the long-face pattern of growth and controlling downward and backward rotation of the mandible is difficult and, at least until now, has been almost impossible. In theory, it should be possible to impede downward growth of the posterior maxilla with high-pull headgear and impede eruption of the posterior teeth in both arches. In fact, even the combination of high-pull headgear with a functional appliance with bite-blocks is not successful in producing the desired skeletal changes. It is possible that an adaptation of the technique for intrusion of the maxillary posterior teeth to correct open bites after adolescent growth, or bone plates across the zygomaticomaxillary suture, can be used to diminish the downward growth of the maxilla that is a key component of long-face development, but there are as yet no data to confirm that.

For modification of vertical growth, the conclusions are the following. Can you produce downward and backward rotation of the mandible and increase the face height when this is required? Yes. Can you produce upward and forward rotation of the mandible, or even maintain its vertical position, in a patient with a long-face pattern? Unfortunately, no, at least not yet.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses