Cerebral palsy is a permanent neuromuscular motor disorder that results from injury in the developing brain during the prenatal or postnatal period. Common functional and craniofacial problems related to cerebral palsy include impaired swallowing, chewing, and speech; maxillary transverse deficiency; excessive anterior facial height; and Class II malocclusion. This article reports the treatment of a 12-year-old girl with ataxic cerebral palsy; she had a dental and skeletal Class II malocclusion, maxillary transverse deficiency, and severe crowding in both arches. Treatment included rapid maxillary expansion with simultaneous functional therapy and fixed orthodontic extraction therapy in a period of 2 years 3 months. Vertical control was maintained by a vertical chincap. An acceptable occlusion and improvements in facial esthetics, speech, and oral function were achieved.

A common definition of cerebral palsy (CP) is a disorder of movement and posture caused by a defect or lesion in the immature brain. A collaborative group called Surveillance of Cerebral Palsy in Europe has classified CP into 4 main types: spastic, ataxic, dyskinetic, and mixed. The most important causes of CP are premature birth, oxygen reduction in the developing brain, and periventricular leukomalacia. Other possible causes include infections of the brain, toxemia of pregnancy, cerebral dysgenesis, kernicterus, poisoning with certain drugs and heavy metals, and head trauma. CP was reported to be related to Class II maloclusion. Rosenbaum et al and Franklin et al found that even though increased overjet and overbite were common in CP patients, malocclusion prevalence was similar to that of the healthy population. Intraoral problems often seen in children with CP include poor oral hygiene, periodontal disease, dental caries, bruxism, trauma, protrusion of the maxillary anterior teeth, excessive overjet and overbite, incompetent lips, open bite, and unilateral crossbite. Facial muscle impairments or habits related to jaw, lip, and tongue movements in patients with CP can result in sucking, chewing, swallowing, and speech problems; drooling; tongue thrust; and temporomandibular disorders. Functional appliance therapy guides skeletal growth and modifies the patient’s neuromuscular behavior, especially masticatory muscle activity. However, some have reported that children with neuromuscular diseases such as CP could not be treated successfully with functional appliances. In a review of the literature, we found no study or case report regarding the benefits and effects of functional or fixed orthodontic appliance therapy in children with CP. The aim of this case report was to present an acceptable orthodontic treatment, including functional appliance treatment, of a patient with ataxic CP.

Etiology and diagnosis

A 12-year-old girl was referred to the orthodontic department of Gazi University in Ankara, Turkey, for diagnosis and treatment. Her parents’ main complaints were her severe crowding, buccally positioned maxillary permanent canines, and unpleasant smile ( Fig 1 ). Her parents reported that the pregnancy and parturition were normal, and she was born in the 40th week of gestation. When she was 50 days old, after a regular feeding session, she vomited and aspirated while asleep. She was quickly hospitalized. During this period, she suffered from high fever. Subsequently, she was evaluated and treated by a multidisciplinary team including a pediatrician, a physiotherapist, a psychologist, and a neurologist. Her diagnosis was ataxic CP and mental retardation (IQ, 35-49). She had problems with balance, coordination, and speech; orthopedic problems; and strabismus. Her walking and talking abilities were delayed until 7 years of age because of her 76% physical disability.

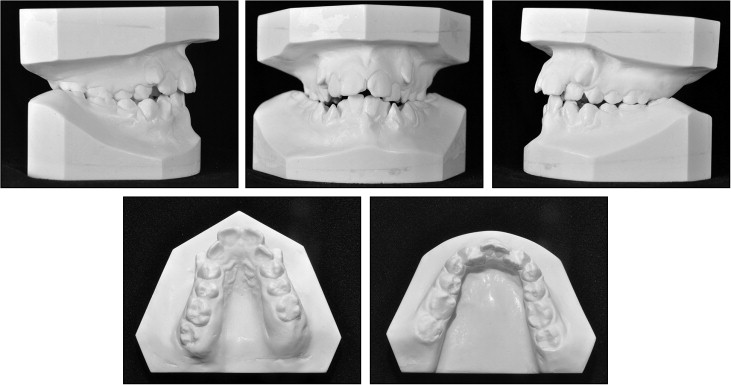

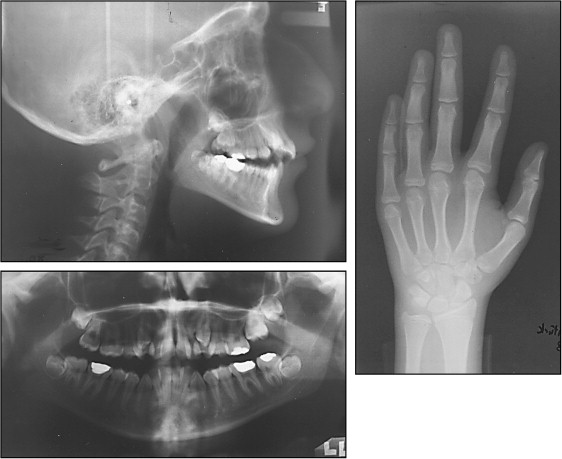

In her oral examination, severe maxillary transverse deficiency with a transverse discrepancy, bilateral posterior crossbite, Angle Class II Division 1 malocclusion with an excessive overjet and a normal overbite ( Table ), fractured permanent maxillary central incisors, and severe crowding in both dental arches were found ( Fig 1 ). The dental cast analysis showed severe arch-length deficiencies in both arches ( Fig 2 ). The hand and wrist radiograph showed that her skeletal age was 14 years with a remaining growth potential of only 1.7% according to the method of Greulich and Pyle and MP3 union skeletal growth stage according to Grave and Brown. Evaluation of the panoramic radiograph showed no congenitally missing teeth, and no periapical pathologies, root abnormalities, or resorption was noted ( Fig 3 ). The pretreatment cephalometric analysis showed a skeletal Class II relationship, a steep mandibular plane angle, reduced effective mandibular length, excessive upper and lower anterior facial heights, a vertical facial growth pattern, and increased articular and steep occlusal plane angles. Both maxillary and mandibular incisor positions were acceptable ( Table ).

| Pretreatment | Phase1 | Phase 2 | Postretention | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-N (mm) | 64.8 | 65.6 | 65.7 | 65.8 |

| NSAr (°) | 122.5 | 120.5 | 122.2 | 122.1 |

| SArGo (°) | 152.9 | 149.1 | 144.7 | 148 |

| ArGoMe (°) | 131.4 | 134.9 | 136.7 | 132.9 |

| Sum of posterior angles (NSAr + SArGo + ArGoMe) (°) | 406.8 | 404.5 | 403.6 | 403 |

| SN-GoGn (°) | 44 | 41.9 | 41.1 | 40.7 |

| N-ANS (perp HP) (mm) | 57 | 56.2 | 56.1 | 55.7 |

| ANS-Me (perp HP) (mm) | 65 | 66.1 | 66.5 | 65.9 |

| SNA (°) | 78 | 78 | 77.8 | 78.2 |

| SNB (°) | 73 | 74.4 | 74.3 | 74.1 |

| ANB (°) | 5 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 4.2 |

| Midface length (Co-A) (mm) | 77.8 | 78.6 | 79.3 | 80.1 |

| Mandibular length (Co-Gn) (mm) | 111.9 | 115.4 | 115.6 | 116.4 |

| U1-SN (°) | 100.9 | 90.8 | 87 | 91.7 |

| U1-NA (mm) | 3.6 | 2.4 | 0.7 | 1.5 |

| U1-NA (°) | 23.3 | 12.7 | 9.2 | 13.5 |

| IMPA (°) | 81.6 | 82.7 | 81.7 | 85.5 |

| L1-NB (mm) | 2.9 | 3.1 | 3 | 3.6 |

| L1-NB (°) | 21.2 | 21.5 | 19.6 | 22.6 |

| Transverse discrepancy (mm) | −8 | 2 | 0 | −2 |

| Arch length deficiency | ||||

| Maxilla (mm) | −15 | −10 | 0 | 0 |

| Mandible (mm) | −12 | −12 | 0 | 0 |

| Overjet (mm) | 7.5 | 5 | 2 | 4 |

| Overbite (mm) | 1.5 | 1.5 | 2 | 2 |

Treatment objectives

The etiology could have been a combination of inherited growth pattern, CP, and weakness of the buccal musculature. The main objectives of the treatment were to (1) expand the maxillary arch to favor the tongue movements and overcome the swallowing, speech, and excessive drooling problems; correct the bilateral posterior crossbites and also obtain a spontaneous forward positioning of the mandible by eliminating the functional interferences caused by maxillary constriction; (2) correct the Class II molar and canine relationships and the convex facial profile with functional therapy, which might serve as myofunctional therapy to achieve better masticatory muscle activity and stimulate the forward growth of the mandible with the remaining growth potential of 1.7%; (3) control the vertical growth; and (4) solve the arch-length discrepancy and align both dental arches by extracting the 4 first premolars to achieve a better occlusion.

Treatment objectives

The etiology could have been a combination of inherited growth pattern, CP, and weakness of the buccal musculature. The main objectives of the treatment were to (1) expand the maxillary arch to favor the tongue movements and overcome the swallowing, speech, and excessive drooling problems; correct the bilateral posterior crossbites and also obtain a spontaneous forward positioning of the mandible by eliminating the functional interferences caused by maxillary constriction; (2) correct the Class II molar and canine relationships and the convex facial profile with functional therapy, which might serve as myofunctional therapy to achieve better masticatory muscle activity and stimulate the forward growth of the mandible with the remaining growth potential of 1.7%; (3) control the vertical growth; and (4) solve the arch-length discrepancy and align both dental arches by extracting the 4 first premolars to achieve a better occlusion.

Treatment alternatives

One benefit of maxillary arch expansion is that space is gained for better tongue movements; this can lead to improvements in speech and swallowing and help eliminate excessive drooling problems. The advantages of functional therapy include improved masticatory muscle activity, lessening of impaired chewing problems, and improved esthetic appearance; these changes would provide physiologic and psychologic advantages for the patient and her parents. The severe mandibular crowding would not permit a nonextraction treatment in the mandibular arch. The only alternative treatment modality was orthognathic surgery, but we decided not to postpone the presurgical treatment, which consisted of rapid maxillary expansion (RME) and fixed appliances.

Treatment progress

Treatment was carried out in 3 phases: (1) RME and functional therapy with a modified Twin-block appliance used simultaneously with RME and an extraoral vertical chincap appliance; (2) fixed appliance treatment with the extraction of the 4 first premolars and an extraoral vertical chincap appliance; and (3) retention. All clinical procedures were carried out by the second author (G.M.-G.). The diagnostic, radiographic, and clinical records before and after these 3 stages were collected and evaluated.

In phase 1, treatment began with RME, which was used in 2 stages because of the severe narrowness of the maxillary arch. The first RME appliance was an acrylic cap splint type with a frame constructed with 0.8-mm round stainless steel hard wire, activated at 1 turn per day until 8 mm of widening was achieved in a period of 1 month 13 days. Next, an acrylic cap splint type of RME appliance, modified by the first author (H.N.İ.) to serve as the upper part of a Twin-block appliance, was bonded to use for functional therapy and also for further expansion of the maxillary arch to overcorrect by 5 mm; this took about 1 month. Although the RME was discontinued after 13 mm of widening, with an overcorrection of the transverse discrepancy, the appliance was not debonded and was left in the mouth for retention and to serve as the upper part of the Twin-block appliance for 3 months. Total duration with the Twin-block therapy was 4 months. The patient was asked to wear a vertical chincap applying 400 g of force beginning from the first RME appliance to the end of the Twin-block therapy to (1) assist the anterior rotation of the mandible, (2) control the vertical increase of the posterior dentoalveolar and anterior facial heights, and (3) stabilize the mandible in forward and closed position by assisting the maxillary and mandibular bite-blocks of the Twin-block appliance to interlock at an angle of 45°. Total duration of phase 1 of treatment was 6 months 25 days. The acrylic splint-type RME appliance was debonded, and a maxillary Essix plate (DENTSPLY Ltd, Surrey, United Kingdom) was placed. At the end of this phase, the mandibular position and occlusion were not stable because of crowding, and a mandibular shift to the right was observed. Fixed appliance therapy in phase 2 of treatment would solve this problem.

In phase 2, the maxillary permanent first molars were banded, and a transpalatal arch was inserted in the palatal tubes of these teeth to maintain the intermolar width. After the extraction of the 4 first premolars, the mandibular first molars were banded, and all the other teeth were bonded with 0.018-in slot Roth brackets (Master brackets, Roth prescription; American Orthodontics, Sheboygan, Wis). The maxillary and mandibular arches were leveled using 0.013-in copper-nickel-titanium and 0.016-in, 0.018-in, 0.016 × 0.022-in, and 0.017 × 0.025-in nickel-titanium and archwires within 6 months. The vertical chincap was used until the end of the leveling phase. Then approximately 5 mm of extraction space was left in the maxilla, and no space was left in the mandible. This space was closed using chain elastics on the 0.016 × 0.022-in stainless steel archwire in the maxillary arch. The lower midline shift caused by the relapse of the RME was corrected with a transpalatal arch and intermaxillary elastics. Because the patient could not attend her appointments for the next 3 months because of her orthopedic surgery, the fixed appliances were removed without correction of the second-order positions of the incisors and any settling procedures. Total duration for this phase (fixed appliance treatment) was 1 year 5 months 22 days ( Figs 4-6 ).