It has been noted that the eyes and brows are the most influential determinants of facial expression. With our continuing pursuit of better understanding of the details of upper facial anatomy, cosmetic surgeons are able to make significant corrections and increase attractiveness of the upper part of the face with relatively minimal invasiveness.

Different regions of the face age at variable rates. The upper third of the face ages in its own unique fashion. Characteristics of the aging brow, temple, eyelids, and face are relatively similar in most people ( Fig. 105-1 ). Gravity, sun exposure, and genetic factors cause the forehead, temple, and glabellar skin to descend. Generally speaking, the aged upper face appears tired, angry, or sad when the changes described take place.

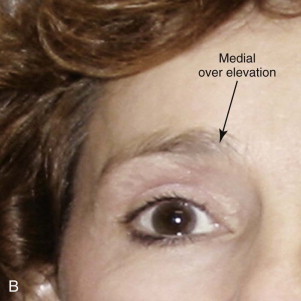

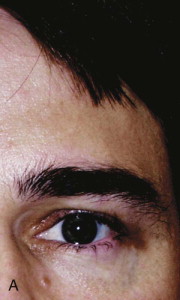

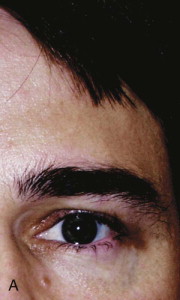

Brow ptosis is a result of inferior migration of the eyebrow below its natural position at the level of the supraorbital bony rim. Clinically, the lateral eyebrow segment almost always becomes ptotic earlier in life than the medial eyebrow segment ( Fig. 105-2 ).

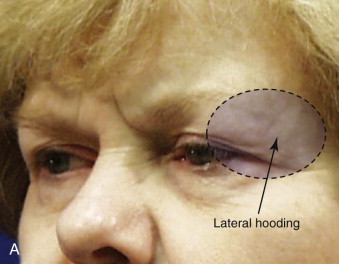

Redundant skin in the upper eyelid (dermatochalasis) is another phenomenon associated with the aging upper face. This “hooding” of the upper eyelids, a result of diminished skin elasticity and tone, can lead to a reduction in visual field acuity and can be cosmetically displeasing to the person affected. Severe upper lid dermatochalasis can lead some patients to constantly exaggerate their elevator muscle action to compensate and maintain as normal a brow position as possible. Raising the forehead is often done subconsciously when the field of vision is being impaired as a result of excessive eyelid laxity over the eye. Blepharoplasty or forehead and brow lifting can often relieve the ptosis over the eye and thereby diminish the subconscious forehead wrinkles ( Fig. 105-3 ). These actions cause skin creases horizontally on the forehead. The frontalis muscle causing most of the upper facial rhytides has been the target and the draw to fame of botulinum toxin (Botox) injection.

Elevation and rejuvenation of the forehead, brow, and upper eyelids have been achieved by reducing the forces that cause dynamic wrinkles on the forehead, as well as by repositioning the involved structures to their normal anatomic position. Endoscopic brow lifting was first introduced in 1991 by Keller. The authors’ personal experience with this procedure began in 1996. Since then, our patients tend to prefer the endoscopic approach over the other open approaches. In the majority of cases, open techniques may still be preferred in patients with a high hairline or deep forehead rhytides.

Endoscopic forehead and eyebrow lifting has a steep learning curve. Specific instruments, as well as fine surgical skill and dexterity, are needed. Furthermore, this procedure requires intimate knowledge of the anatomy associated with the forehead and peri-orbital structures. However, once mastered, the procedure offers the patient an elegant surgery with no hair or skin removal and an exceedingly rejuvenated appearance.

Etiopathogenesis

Facial changes can have an impact on quality of life. Rejuvenating the upper third of the face may be very rewarding to the patient and the cosmetic surgeon. Specific age-related changes in upper facial appearance can be dealt with on an individual basis or by a combination of procedures to result in maximal return of youthfulness.

The endoscopic forehead and brow lift, when properly performed, can address brow ptosis in addition to dynamic muscular problems. Before diagnosing and treating these problems the surgeon must be familiar with the different changes that the aging face experiences, as well as the possible associated causes.

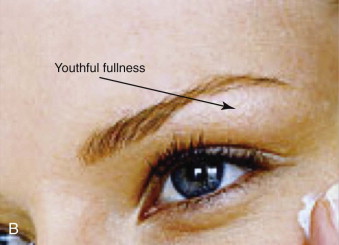

Our basic understanding of the aging process is typically that the forehead, brow, and upper eyelids droop and sink because of gravitational forces and muscle activity or hyperactivity. Pioneering work by several authors has shown that gravity is not the sole determinant of the aging face. These authors have demonstrated that loss of volume, including that of soft tissue and bone, is at least equally important in the pathogenesis of the stigmata of aging ( Fig. 105-4 ). On the one hand, depletion of volume appears to be the major contributor not only to wrinkles but also to descent or sagging of the tissues; on the other hand, recent studies have shown that sun damage is probably just as important in the process of aging as gravity and loss of volume.

We know that photodamage specifically causes considerable collagen deterioration and elastin reorganization, as well as depletion of the water barrier in the stratum corneum. Aged skin shows atrophy of the epidermis with straightening of the rete pegs. There is a moderate decrease in the number of Langerhans cells. Dryness of the skin (xerosis cutis) is a common phenomenon. This was found to be related not to the production of sebum but to lowering of intrinsic epidermal fat and poorer retention of water. Photodamaged dermis has less cellularity and a decrease in elastic fibers, which leads to less skin elasticity.

The cumulative effects of gravity on this less elastic skin and decreased volume of subcutaneous tissue evolve into brow ptosis. The development of deep forehead furrows arises from the repeated action of facial mimetic muscles on the overlying skin.

As brow ptosis progresses, dermatochalasis of the upper lids may develop. When a patient is evaluated for blepharoplasty, it is important to consider whether the dermatochalasis is the result of redundant upper eyelid skin, a manifestation of ptotic forehead skin, or both ( Fig. 105-5 ). Failure to recognize the cause of this deformity may result in fixation of the brow in an inappropriate position or incorrectly performing a blepharoplasty, which may result in less than ideal upper eyelid length.

Sun, smoking, nutrition, and dynamic muscle function all contribute to the etiopathogenesis of upper facial aging. However, a genetic predisposition to brow ptosis is one of the most notable causes of premature upper facial third aging that would benefit from cosmetic enhancement.

Pathologic Anatomy

To rejuvenate the aging brow, one must have a fundamental understanding of the ideal brow position. In addition, the surgeon must understand the relationships between the skin, subcutaneous adipose tissue, muscle, and the deep fascial layers and their variations throughout the forehead.

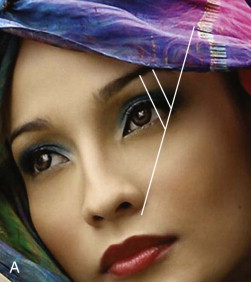

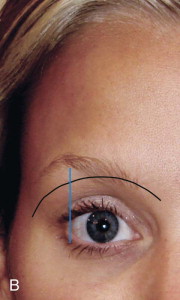

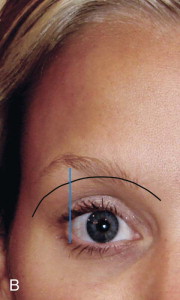

Significant differences exist between the eyebrows of men and women ( Fig. 105-6 ). In men, the hairs are embedded in thicker subcutaneous fat, which in turn rests on a prominence created by multiple muscle layers, the brow fat pad, and the underlying bony ridge. The typical male eyebrow should lie at or only slightly above the orbital rim in a more horizontal or uniform arch fashion, whereas the female eyebrow should be arched well above the superior orbital rim, with the highest point of the brow lying on a sagittal line from the lateral canthus.

There are classically five layers covering the forehead ( Fig. 105-7 ): skin, a subcutaneous layer of fibrofatty tissue, muscular aponeurosis sheath, loose areolar tissue connecting the galea aponeurosis sheath to the fifth layer, and the deepest layer, the periosteum or pericranium.

Skin is thinner more cephalad and thicker nearer the eyebrow and glabellar areas. The skin lines of the forehead occur in a relatively standard pattern of transverse mid-forehead lines, vertical glabellar lines, and transverse radix lines.

Aged skin is noted to have thinning of the dermis, which makes the skin less elastic and more prone to wrinkling. Subcutaneous tissue is already thin in the upper part of the face, and with normal aging, this layer also becomes comparatively thinner.

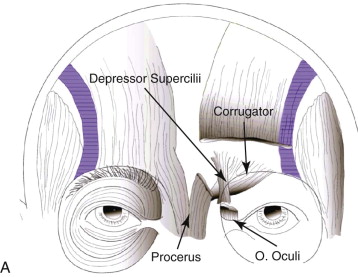

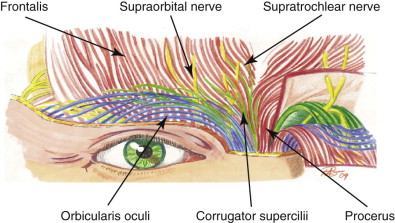

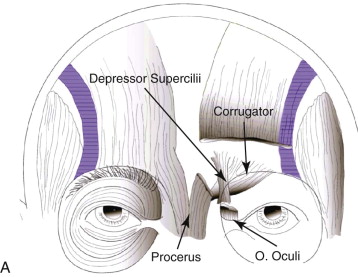

Horizontal forehead furrows result from contraction of the underlying frontalis muscle during eyebrow elevation. The frontalis muscle happens to be the only brow elevator. Several other depressor muscles play major roles in facial expression and cause the signs associated with aging skin. These depressor muscles are the corrugator supercilii, procerus, depressor supercilii, and orbicularis oculi muscles ( Fig. 105-8 ).

The procerus muscle is a continuation of the frontalis muscle. It originates on the nasal bones and inserts cephalad into the frontalis muscle fibers and then onto the dermis. Contraction of this pyramidal-shaped muscle creates horizontal rhytides overlying the radix (bunny lines). This muscle is usually transected when performing an endoscopic brow lift.

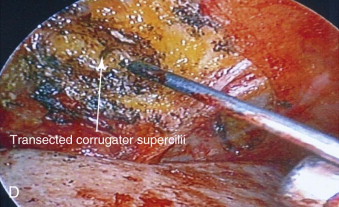

Similarly, the action of the corrugator supercilii muscle causes inferomedial contraction of the space between the brows and results in vertical and horizontal glabellar wrinkling. The corrugator originates from the inferior edge of the frontal bone, at the junction of the nasal bone and frontal bones, and inserts into the dermis of the medial aspect of the brow. This muscle has two heads, oblique and transverse, both of which need to be addressed when performing a forehead lift procedure.

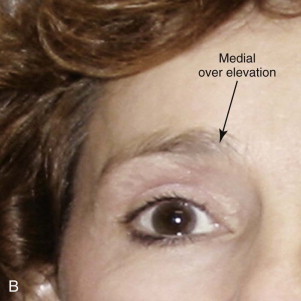

The depressor supercilii muscle also plays a role in causing the forehead to depress. It originates on the frontal process of the maxilla and inserts into the medial frontalis fibers and dermis just above the medial brow region. Dissection through this muscle during endoscopic brow lifts can be the difference between a successful result and an overly elevated medial brow ( Fig. 105-9 ).

The orbicularis oculi muscle has three parts whose description is based on location: the pretarsal, preseptal, and orbital segments. It arises from the nasal portion of the frontal bone and also from the frontal process of the maxilla in front of the lacrimal groove . When the entire muscle is brought into action, the eyebrow, temple, and cheek are drawn toward each other to close the eyelids firmly shut. Transection of the lateral orbital portion of the orbicularis muscle is usually necessary for an adequate upper third face-lift procedure.

The frontalis muscle fibers originate from the deep galeal fascia and insert into the orbital portion of the orbicularis oculi and then into the dermis just below the eyebrow. Laterally in the temporal region, the frontalis muscle fuses into a dense fascial layer known as the zone of adherence. This zone connects the galea of the upper part of the face with the superficial fascial system of the lower part of the face. Understanding the fascial layers of this confluence is crucial since releasing it is required for the long-term lift desired when performing an endoscopic brow lift.

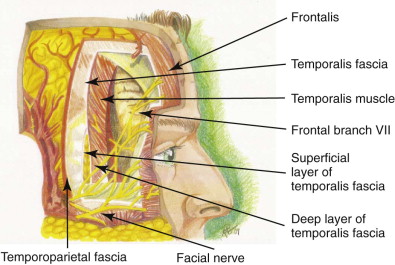

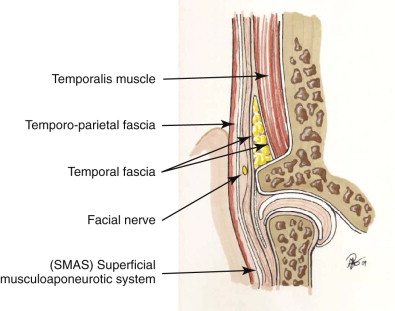

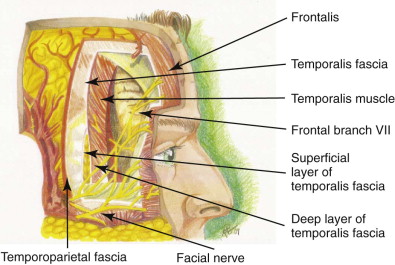

The temporoparietal (spongy) fascia is in continuity with the galea aponeurotica. This layer contains the superficial temporal artery and the frontal branch of the facial nerve ( Fig. 105-10 ). The deep temporal fascia is thicker and has a white glistening appearance. Below the zygomatic arch, this deep temporal fascia splits into two layers called the intermediate temporal and deep temporal fasciae. The temporoparietal fascia is in continuity with the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) below the zygomatic arch and the galea aponeurotica, which in turn is in continuity with the frontalis muscle.

Detailed understanding of the fascial layers and their relationship to the muscles just described, as well as the relationship of these layers to bones and significant vessels in the region, is essential to perform a safe and successful eyebrow lift procedure.

The frontal bone makes up most of the upper third of the face. The bones involved in brow lift procedures include the frontal, maxillary, zygomatic, temporal, and nasal bones. The suture lines connecting these bones include the coronal, nasofrontal, zygomaticofrontal, and zygomaticotemporal processes. The three bones involved in forming the orbital rim are the frontal, zygomatic, and maxillary bones. The zygomaticofrontal suture line is the landmark for ending most basic brow lift dissections.

Awareness of bone thickness in different locations of the skull is of absolute importance when performing a lifting procedure. If bone tunnels or screws are planned for fixation, the midline should be avoided because of the sagittal sinus, as well as the venous lakes in the mid-frontal area of the cranium. The lateral position of the middle meningeal artery should be noted and avoided near the thin, petrous portion of the parietal bone. The safest placement for tunnels and screws is along a parasagittal line located approximately at the mid-pupil or just anterior to the coronal suture.

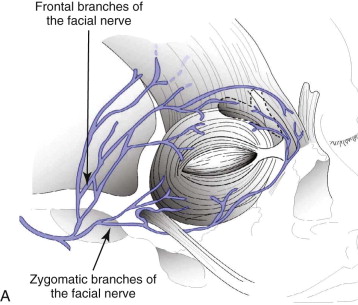

Knowledge of the facial nerve is paramount when operating on the face. Endoscopic forehead, temporal, and maxillary dissection provides more opportunity to learn the anatomy of the face from a different perspective. The facial nerve emerges from the substance of the parotid gland in the form of several branches and remains deep to the SMAS. The five branches are the temporal, zygomatic, buccal, mandibular, and cervical nerves.

The temporal (frontal) branch of the facial nerve exits the superior aspect of the parotid gland below the SMAS and eventually crosses the zygomatic arch, usually in multiple branches. Above the arch, the nerve travels in the temporoparietal fascia and enters the lateral part of the frontalis muscle and superior part of the orbicularis oculi. Dissection in this temporal lateral area during a combined forehead lift and face-lift generally requires two planes of dissection. The forehead lift usually involves dissection in the temporal area below the temporoparietal fascia, whereas the face-lift dissection is performed in the subcutaneous plane to avoid injury to the temporal nerve that lies between the two levels of dissection. The temporal and zygomatic branches share the nerve supply to the orbicularis oculi, the corrugator supercilii, and the procerus.

It is of importance during dissection to differentiate between the auriculotemporal nerve and the temporal (frontal) nerves. The auriculotemporal nerve (from the trigeminal nerve) supplies sensation to the front of the ear and the skin over the zygomatic arch. This nerve runs 1 cm anterior to the tragus of the ear, whereas the more important temporal branch of the facial nerve runs an average of 2 cm anterior to the tragus when crossing the zygomatic arch. As mentioned earlier, the superficial temporal fascia is continuous with the galea aponeurosis, which contains the superficial temporal artery, the temporal branch of the facial nerve, and the auriculotemporal nerve.

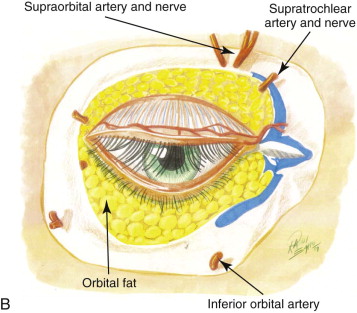

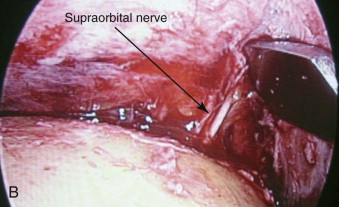

Sensation to the skin covering the face is supplied by the trigeminal nerve. The auriculotemporal nerve supplies the lateral ear and zygoma region with sensation, and the scalp and eyebrow are innervated by the supratrochlear and supraorbital nerves. The supraorbital nerve exits the supraorbital foramen, whereas the supratrochlear nerves exit from around the orbital rim approximately 1 cm medial to the exit of the supraorbital nerve. The supraorbital nerve divides after exiting the cranium into deep and superficial branches. The topographic landmark for the course of the supraorbital nerve at the supraorbital rim reliably lines up with the medial limbus of the iris. The deep (or lateral) division supplies the lateral posterior area of the forehead and scalp, and the superficial (or medial) division enters the frontalis and supplies sensation to the anterior forehead region. The infratrochlear nerves supply sensation to the medial orbital rim and upper part of the nose. These nerves exit just below the supratrochlear nerves ( Fig. 105-11 ).

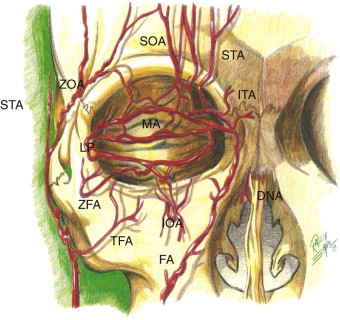

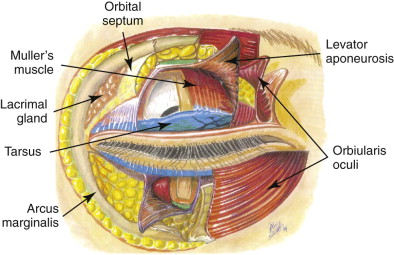

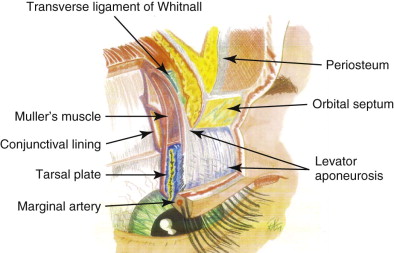

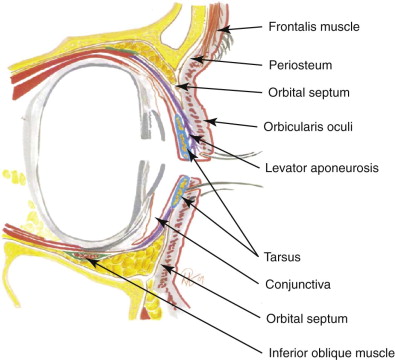

Since eyelid evaluation and possible intervention play a role in rejuvenating the upper third of the face, the anatomy of the eyelids needs to be addressed. The skin of the eyelid is extremely thin and well vascularized. Typically, the arterial supply runs parallel with the sensory and motor nerves ( Fig. 105-12 ). The upper eyelid skin has very little subcutaneous tissue but is firmly adherent to the underlying orbicularis oculi muscle. The orbicularis muscle is divided into pretarsal, preseptal, and orbital components ( Fig. 105-13 ). Deep to the orbicularis is the orbital septum, a thin fibrous sheet that originates at the orbital rim and is in continuity with the orbital periosteum ( Fig. 105-14 ). The septum fuses with the levator aponeurosis above the superior tarsal border. The tarsal plate and conjunctiva lie deep to the orbital septum ( Fig. 105-15 ).

The upper eyelid has two pre-aponeurotic fat pads, the central and medial compartments, that lie between the orbital septum and the levator aponeurosis. The medial fat pads are the most often addressed pads during blepharoplasty. The lacrimal gland occupies the lateral aspect of the orbit and may only rarely need lifting, as in the case of prolapse affecting the visual field. Upper eyelid resection (blepharoplasty) is sometimes combined with a forehead and brow lift for an optimal result ( Fig. 105-16 ).

The levator palpebrae superioris muscle originates at the lesser wing of the sphenoid and inserts into the inferior part of the tarsus and into the orbicularis muscle and skin. This insertion into the skin and muscle of the upper eyelid forms the upper eyelid crease, which falls approximately 1 cm above the upper eyelid margin. The levator and Müller muscle act as the eyelid retractors.

Endoscopic Anatomy

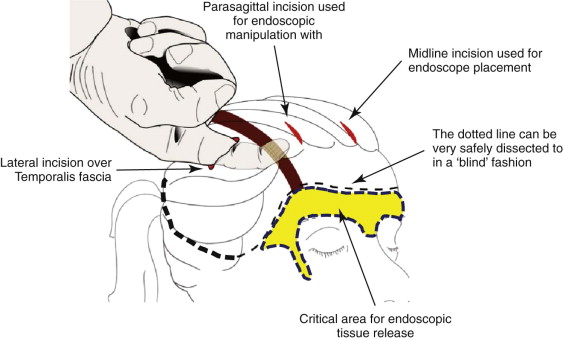

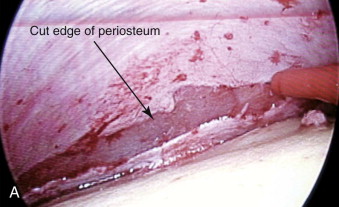

Access must be gained by the endoscope for release of the eyebrow from its periosteal attachments. Through incisions to be discussed later in the chapter, blunt dissection is performed in the subperiosteal plane to approximately 2 cm away from the orbital rim and zygomatic arch. The last 2 cm needs to be dissected under endoscopic visual guidance. Laterally, it is the authors’ advice to dissect above the superficial temporal fascia through the lateral incisions and connect into the central subperiosteal plane, the “safe zone” ( Fig. 105-17 ). Staying deep to the periosteum prevents injury to the deep divisions and branches of the supraorbital nerve that lie in the subgaleal plane near the zone of fixation. Dissection posteriorly toward the occiput is also performed in the subperiosteal or sometimes in the subgaleal plane to create room for scalp elevation and aid in providing space for and maneuverability of the endoscope.

Attention is first directed to the lateral aspect of the elevated forehead flap. The zone of fixation begins at the lateral corner of the superior orbital rim. Again, this is the point where all the fascial layers come together. Dissection laterally in this position to expose the lateral orbicularis oculi and release the zone of fascial convergence needs to be precise. The temporal branch of the facial nerve curves medially in this area during its upward path toward the forehead, and care should be taken to not injure it. Another structure that the cosmetic surgeon will become acquainted with in this lateral corner is the sentinel vein, which is situated approximately 1 cm lateral to the zygomaticofrontal suture line. This vein can be seen going through the temporoparietal fascia at a perpendicular angle. The sentinel vein can be sacrificed, but care must be taken to not cauterize the area where the vein can retract and continue to bleed.

The central dissection plane takes the surgeon down to the level of the superior orbital rim, where the entire superior rim should be visualized. The endoscope should provide a good view of the periosteum elevated in a relatively bloodless plane. Dissection through the periosteum will reveal the subgaleal fat, except at the supraorbital nerve level. The nerve, artery, and their branches can be seen penetrating the fascial layers toward the frontalis and subcutaneous tissue and originating from the supraorbital notch in alignment with the medial limbus. While dissecting further superficially toward the muscles of the glabella and medial eyebrow, the surgeon should keep in mind the position of the supraorbital nerve and artery. The supraorbital nerve, as mentioned earlier, runs in line with the medial limbus of the eyebrow. Medial to this nerve bundle, the corrugator supercilii can be seen with its two heads. Once the oblique head of the corrugator is transected, the supratrochlear nerve and depressor supercilii muscle are encountered and should be avoided unless over-elevation is needed by transecting the depressor supercilii muscle ( Figs. 105-18 and 105-19 ). Looking further medially in the glabella will show the procerus muscle, which should also be sacrificed for adequate forehead release while keeping in mind that it is a thin muscle and that an overly aggressive transection technique can penetrate through the skin. Continued dissection toward the skin will then expose the orbicularis oculi, which is typically not disrupted medially unless preoperative evaluation has revealed a need to do so; instead, this muscle will be transected rather laterally to gain lateral eyebrow elevation and a reduction in crow’s feet rhytides. In patients with deep horizontal furrows, the periosteum and its overlying fascial layers can be transected along the forehead flap for moderate reduction of these forehead rhytides.

Pathologic Anatomy

To rejuvenate the aging brow, one must have a fundamental understanding of the ideal brow position. In addition, the surgeon must understand the relationships between the skin, subcutaneous adipose tissue, muscle, and the deep fascial layers and their variations throughout the forehead.

Significant differences exist between the eyebrows of men and women ( Fig. 105-6 ). In men, the hairs are embedded in thicker subcutaneous fat, which in turn rests on a prominence created by multiple muscle layers, the brow fat pad, and the underlying bony ridge. The typical male eyebrow should lie at or only slightly above the orbital rim in a more horizontal or uniform arch fashion, whereas the female eyebrow should be arched well above the superior orbital rim, with the highest point of the brow lying on a sagittal line from the lateral canthus.

There are classically five layers covering the forehead ( Fig. 105-7 ): skin, a subcutaneous layer of fibrofatty tissue, muscular aponeurosis sheath, loose areolar tissue connecting the galea aponeurosis sheath to the fifth layer, and the deepest layer, the periosteum or pericranium.

Skin is thinner more cephalad and thicker nearer the eyebrow and glabellar areas. The skin lines of the forehead occur in a relatively standard pattern of transverse mid-forehead lines, vertical glabellar lines, and transverse radix lines.

Aged skin is noted to have thinning of the dermis, which makes the skin less elastic and more prone to wrinkling. Subcutaneous tissue is already thin in the upper part of the face, and with normal aging, this layer also becomes comparatively thinner.

Horizontal forehead furrows result from contraction of the underlying frontalis muscle during eyebrow elevation. The frontalis muscle happens to be the only brow elevator. Several other depressor muscles play major roles in facial expression and cause the signs associated with aging skin. These depressor muscles are the corrugator supercilii, procerus, depressor supercilii, and orbicularis oculi muscles ( Fig. 105-8 ).

The procerus muscle is a continuation of the frontalis muscle. It originates on the nasal bones and inserts cephalad into the frontalis muscle fibers and then onto the dermis. Contraction of this pyramidal-shaped muscle creates horizontal rhytides overlying the radix (bunny lines). This muscle is usually transected when performing an endoscopic brow lift.

Similarly, the action of the corrugator supercilii muscle causes inferomedial contraction of the space between the brows and results in vertical and horizontal glabellar wrinkling. The corrugator originates from the inferior edge of the frontal bone, at the junction of the nasal bone and frontal bones, and inserts into the dermis of the medial aspect of the brow. This muscle has two heads, oblique and transverse, both of which need to be addressed when performing a forehead lift procedure.

The depressor supercilii muscle also plays a role in causing the forehead to depress. It originates on the frontal process of the maxilla and inserts into the medial frontalis fibers and dermis just above the medial brow region. Dissection through this muscle during endoscopic brow lifts can be the difference between a successful result and an overly elevated medial brow ( Fig. 105-9 ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses