Introduction

Great strides in pediatric cancer treatment are allowing hundreds of thousands of children to survive into adulthood. However, these treatments can be responsible for long-term medical and dental complications. The treatments may alter the patients’ dental health and require modifications to standard orthodontic care. The aim of this study was to examine knowledge and clinical experience regarding orthodontic management of childhood cancer survivors.

Methods

A 12-question online survey consisting of 3 sections was sent to 2500 randomly selected members of the American Association of Orthodontists and all 2300 members of the Southern Association of Orthodontists. The first section consisted of questions about the respondents’ practice characteristics, the second questioned how many survivor patients the respondent had treated, and the third included questions about specific (anonymous) patient experiences and treatment modifications.

Results and Conclusions

There were 381 responses. The data from this study suggest a tendency for more experienced practitioners to have treated survivors of childhood cancer. Orthodontic education regarding the treatment of these patients is limited. Although most orthodontists reported having treated such patients, few had treated more than 10. There is a need for more information regarding dental complications of pediatric cancer treatment and for guidelines for the orthodontic treatment of these patients.

Highlights

- •

Few practitioners have treated more than 10 pediatric cancer patients.

- •

Most obtain medical information about the patients’ previous cancer treatment.

- •

Orthodontic education about treatment of survivors of pediatric cancer is limited.

- •

More information is needed on dental complications of pediatric cancer treatment.

Great strides in pediatric cancer treatment have resulted in hundreds of thousands of children living into adolescence and adulthood. With 5-year survival rates as high as 93.5%, these therapeutic improvements have resulted in an estimated 380,000 survivors of childhood cancer in the United States. In many instances, the treatment that has saved these patients’ lives is responsible for many medical and dental complications, which can occur months to years after the patient has completed treatment. According to Geenen et al, nearly 75% of long-term cancer survivors will experience some adverse treatment sequelae in their lifetime. These effects can be caused by the cancer itself, the treatment rendered, the supportive care, the immunosuppressive therapy needed, or a combination of these factors.

Among the 12 major types of childhood cancers, leukemias, lymphomas, and cancers of the brain and central nervous system account for more than half of all new cases each year. Radiation, chemotherapy, surgery, and bone marrow transplantation, used alone or in combinations, are the essential elements in the treatment of childhood cancers.

In pediatrics, some cancer treatments can affect the development of cranial bones, cervical vertebral bodies, and oral cavity structures including teeth and jaws. Common adverse effects of cancer therapy on dental development include arrested root development, microdontia, enamel disturbances, premature apical closure, and aplasia. According to Kaste et al, the patient’s age at the time of the therapeutic intervention is an important factor in the development and degree of these oral complications.

As childhood cancer survival rates increase, more survivors may be seeking orthodontic treatment. According to Dahllof and Huggare, some long-term survivors are at a particular risk of complications during orthodontic treatment because of disturbances in dental development and growth of the craniofacial skeleton; knowledge of these risk factors is essential. Orthodontists need to be aware of previous treatments and their ramifications on the planned orthodontic treatment. A patient’s dental condition may require modifications to standard orthodontic care to prevent or reduce adverse treatment outcomes. However, this information regarding childhood cancer treatment and the sequelae is often not emphasized in the curriculum of orthodontic training programs.

Therefore, the aims of this study were to examine actual and self-perceived knowledge and clinical experiences regarding the orthodontic management of childhood and adolescent cancer survivors, to estimate the frequency of adverse dental complications encountered in these patients, and to catalog reported treatment modifications required to adequately provide orthodontic care for this population.

Material and methods

To examine orthodontists’ knowledge and management of the treatment of childhood cancer survivors, a 12-question survey was drafted. To protect the participants’ personal information, the survey was anonymous and was approved by the University of Tennessee internal review board.

Members of the American Association of Orthodontists (AAO), through the AAO’s Partners in Research program, were invited to participate in a Web-based survey. The survey was sent by e-mail to a randomly selected group of 2500 orthodontists registered with the AAO. An additional reminder e-mail was sent 14 days later to reinforce participation in the survey. In addition, the 2300 members of the Southern Association of Orthodontists (SAO) were invited to participate. An introductory letter was attached to each e-mail message describing the survey and asking for participation in the study. The letter described the study, its purpose, and research goals, and ensured confidentiality.

The survey consisted of 3 sections and was formatted with the online survey software from Qualtrics (Provo, Utah). The first section of 5 questions acquired demographic information regarding the respondents’ location, number of years in practice, number of case starts per year, extent of formal orthodontic education, experience in the treatment of childhood cancer survivors, and practice experience involving treatment of childhood cancer survivors. Respondents who reported no treatment of these patients exited the survey after completing these 5 questions. The second section of 2 questions asked the participants to state the number of childhood cancer survivors they had treated throughout their career in orthodontics and established their willingness to answer questions about these patients. The third section of the survey included 5 questions about individual patient experiences and information. The practitioner was instructed to answer this last question set for each patient. The questions sought responses regarding medical history, the reported age at which the patient received the cancer treatment, the type of cancer treatment, and the dental complications observed, and whether any of a list of common orthodontic modifications was prescribed.

Statistical analysis

All completed surveys were assigned an identification number. All responses were then imported into an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft, Redmond, Wash). Descriptive statistics and chi-square tests were used to assess statistically significant differences between groups ( P <0.05). Further analysis for odds ratios and relative risks were used to assess the effects of certain treatment modalities selected from the chi-square analyses on treatment outcomes. All statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS statistics software (version 22; IBM, Armonk, NY).

Results

Three hundred eighty-one practitioners (7.9% of those invited to participate) successfully completed the survey. The profiles of these respondents are presented in the Table . The majority of the participants identified themselves as having practiced for more than 20 years, with a practice that currently starts 200 to 499 new patients per year.

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Years in practice | ||

| 1-10 | 65 | 17.1 |

| 11-20 | 73 | 19.2 |

| 21-30 | 119 | 31.2 |

| 30+ | 124 | 32.5 |

| Case starts per year (n) | ||

| 1-99 | 49 | 13.0 |

| 100-199 | 113 | 30.0 |

| 200-499 | 188 | 49.6 |

| 500+ | 28 | 7.4 |

| Childhood cancer survivor patients treated (n) | ||

| 1-10 | 168 | 79.2 |

| 11-20 | 37 | 17.5 |

| 21-30 | 4 | 1.9 |

| 30+ | 3 | 1.4 |

When asked whether their orthodontic education had included experience with treating childhood cancer survivors, 85% of the respondents answered no; no explanatory statements were solicited or volunteered with this response. The participants were then asked whether they had treated patients who survived childhood cancer. Fifty-seven percent (n = 218) indicated treating at least 1 survivor of childhood cancer, whereas 43% (n = 163) reported no such experience. Only those who had experience in these treatments were asked to complete the remainder of the survey questions.

Practitioners who had treated survivors of childhood cancer were then asked to quantify by range (1-10, 11-20, 21-30, and 30+) the number of cancer survivors they had treated during their career. The majority (79.2%) of the respondents reported treatments for 1 to 10 patients. However, some respondents reported having treated more than 30 survivors of childhood cancer ( Table ).

The responders who had provided care for survivors of childhood cancer were then requested to answer a set of questions concerning their experiences with each patient. The majority of respondents (92.5%) answered yes, indicating their willingness to continue with the survey; those answering no (7.5%) exited from the survey at this point.

The participants reported 218 patient experiences. Of those, 80.6% of the participants reported having obtained additional medical information regarding the cancer treatment, whereas 19.4% did not.

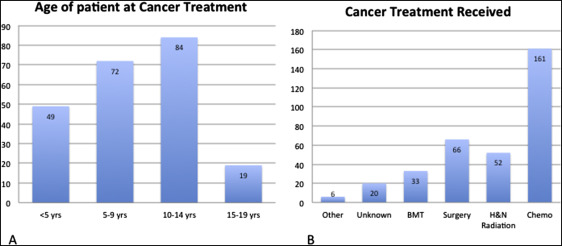

The ages at which the patients reported receiving their cancer treatment are presented in Figure 1 . The distribution by age shows that most patients were treated between the ages of 5 to 9 and 10 to 14 years.

The patients’ reported types of cancer treatment included chemotherapy alone or in combination. This was the most frequently reported cancer therapy. Surgery, head and neck radiation, and bone marrow transplantation were reported in order of decreasing frequency ( Fig 1 ).

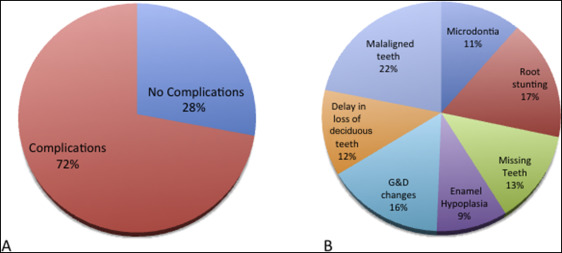

At least 1 dental complication was reported in 72% of the patients. The providers reported malaligned teeth as the most common dental problem, followed by root stunting, and growth and development changes. Twenty-eight percent of the patients had no dental complications ( Fig 2 ).