Evidence-based medicine requires the integration of best research evidence with the clinician’s expertise and the patient’s unique values and circumstances. One of the most important issues in deciding what course of treatment to select is balancing the potential risks and benefits of treatment. A framework for evidence-based decision-making includes formulating the clinical question and then retrieving, appraising, and considering the applicability of the evidence to the patient. It is the duty of all health care providers to reduce patient risk by selecting appropriate therapies and informing patients of unavoidable risks.

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) is “the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients.” It requires the integration of best research evidence with the clinician’s expertise and the patient’s unique values and circumstances. One of the most important issues in deciding what course of treatment to select is balancing the potential risks and benefits of treatment. A framework for evidence-based decision-making includes formulating the clinical question and then retrieving, appraising, and considering the applicability of the evidence to the patient.

Clinical scenario

To illustrate the process of using evidence-based medicine to quantify harm, consider the following clinical scenario. A 62-year-old postmenopausal woman has recently been diagnosed with generalized chronic periodontitis of advanced severity. She has recently received nonsurgical therapy (ie, scaling and root planing, oral hygiene, re-evaluation of treatment response), but problems persist at some sites (eg, bleeding, attachment loss, and probing depths ≥6 mm) and the general dentist has referred the patient to you, the periodontist, for evaluation and treatment. The dentist has suggested that surgical debridement may be indicated in the posterior sextants of the patient’s mouth. You examine the patient and concur with the dentist’s assessment. However, there is a complicating factor in this patient’s history. She has osteoporosis, for which she has taken alendronate for 5 years. Bisphosphonates (BPs), including alendronate, have been associated with osteonecrosis of the jaws, a condition often referred to as “bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws” (BRONJ). While this has been a rare occurrence, the consequences have been catastrophic in some cases. A recent study reported that repeated surgical interventions were required in more than 25% of patients suffering from BRONJ. Some patients have required aggressive (and occasionally disfiguring) surgeries, such as partial maxillectomy and mandibulectomy, sometimes with serious sequelae, such as septic shock. Given this situation, what information do you need to adequately advise your patient about the risks and benefits of treatment for her condition?

This evidence-based decision-making process includes consideration of (1) the risks associated with the procedure (viz, open flap debridement), (2) the risks associated with alternative treatment (eg, additional nonsurgical therapy with or without adjunctive aids, such as antibiotics), and (3) the risk of periodontal infection in the absence of treatment. With regard to the potential risk of BRONJ posed by nonsurgical therapy or untreated periodontal disease, there is insufficient evidence to assess this risk. There are no reports of BRONJ subsequent to nonsurgical periodontal therapy, and while there are reports of BRONJ occurring in the absence of dental treatment, there is little data on the presence of pre-existing periodontal disease as a risk factor. One group has reported periodontal disease as a comorbidity in 84% of a series of 119 cases of BRONJ. However, the investigators do not define what constitutes periodontitis. They do report severe periodontitis as a precipitating factor in 28% of their cases, but it is not clear whether the periodontitis was in conjunction with other risk factors or not. It is of interest that approximately 25% of their cases occurred in the absence of precipitating dental intervention or trauma. The cases reported are a composite of patients referred to the investigators surgical service and “43 cases well documented by colleagues.” This study constitutes a rather low level of evidence. Thus, the inivestigators can make no inferences as to whether untreated periodontal disease might predispose to BRONJ. The risk of no intervention is probably not zero, but it is unknown.

In order to provide optimal care for our hypothetical patient, we must find evidence that will allow us to quantify the risk of BRONJ subsequent to periodontal surgery. We will do this by locating and evaluating high-quality evidence relating to this question. Following an appraisal of the evidence, we will be better prepared to advise our patient, who can decide what option is best for her.

Finding the evidence

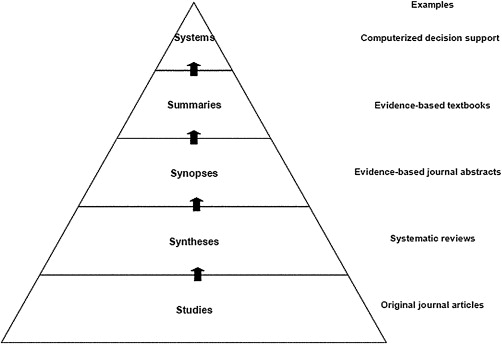

Based on the scenario, we have posed the following question: what is the risk of BRONJ in a postmenopausal woman who has taken alendronate for 5 years. To answer the question, we must match the question to the appropriate study type. Since this is a question of harm, it is best addressed by a systematic review of randomized trials or a single large randomized trial. As reported elsewhere in this issue (Thomas and colleagues), evidence can be ranked on the basis of quality. For therapy questions, systematic reviews and meta-analyses combine results from a number of randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) and, therefore, are regarded as the highest quality evidence, assuming the studies were well-designed and had adequate statistical power to detect differences between modalities. It is common to speak of a “hierarchy” of evidence, often depicted in the form of a pyramid such as the “5S” model proposed by Haynes ( Fig. 1 ).

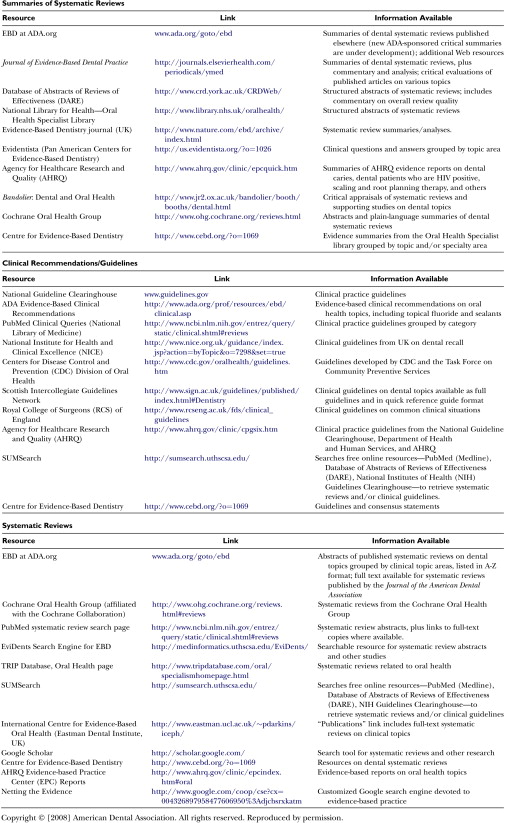

Note in Fig. 1 that individual studies are to be found at the lowest level of the pyramid. Obviously, individual RCTs are the bedrock or foundation of the pyramid, but evidence is strengthened when it is based upon syntheses of a number of well-designed studies. Systematic reviews are syntheses based on the results of multiple RCTs. Such reviews may be found in various repositories, the most well known of which is the Cochrane Library ( www.cochane.org ). Other sources of evidence are listed in Figs. 2 and 3 . A systematic review is a comprehensive search of the literature on a specific question. In this process, there are explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria used to determine what studies should be included in the analysis, as well as an explicit description of the search methodology and results. The meta-analysis is a statistical synthesis of the data from several studies of similar design, with studies weighted with regard to sample size. It is often of value when several RCTs have been performed which, individually, lack the statistical power to detect statistically significant differences between interventions, but are capable of doing so in the aggregate.

“Synopses” refer to brief critical analyses of original articles and reviews that are found in evidence-based journals, such as The Journal of Evidence-Based Dental Practice or the ACP Journal Club . The next level includes summaries, which integrate the best evidence from the lower levels (relying on systematic reviews whenever possible). Summaries integrate the whole spectrum of evidence concerning the management of a particular health issue, such as colon cancer, periodontitis, or metabolic syndrome. Such a summary brings together evidence from individual studies, systematic reviews, and synopses in one compiled and easily accessible source. Of course, it is necessary that the user of such evidence must exercise due diligence by critically appraising the methodology used to create the summary. This appraisal “should include details of the retrieval process used to find best evidence, the appraisal process for rating the quality of evidence should be explicit and auditable, [and] key references provided for all care recommendations.”

There is one level beyond the summary. Clinical-decision support systems link the patient’s electronic health record to current best-evidence based on the individual patient’s clinical circumstances. There are few such systems currently available, and those that exist are limited in their scope and have proven imperfect in application. However, the pieces are in place that can make the continued evolution of such systems likely.

In the case study described above, we could locate no summaries or synopses that addressed our question, so an initial search was conducted in the Cochrane Library, using the search terms “bisphosphonate” AND “oral” OR “jaw.” Three recent reviews were found. Wells and colleagues analyzed results of seven trials involving 14,000 women in which risedronate was compared with a placebo. The investigators report that “[f]or adverse events, no statistically significant differences were found in any of the included studies. However , observational data has led to concerns regarding the potential risk for upper gastrointestinal injury and , less commonly , osteonecrosis of the jaw ” (emphasis added). Note that the investigators are not referring to their reviewed trials when discussing the possibility of osteonecrosis but to other published cases and case series. This review represents a very high level of evidence. Another review (by the same investigators) examined 11 trials of alendronate involving over 12,000 women. Again, there was no statistical difference between the adverse events seen in the test and placebo arms, although the investigators also report the caveat noted above regarding observational studies. This study is even more relevant to the patient in the case study, because subjects in the test arm were administered the same bisphosphonate that the patient in the case study is taking.

The third review in the Cochrane examined 21 RCTs of intravenous bisphosphonate use in metastatic breast cancer. Again, no serious adverse effects were noted, but the investigators include the caveat that BRONJ has been reported in subsequent case reports and observational studies. Thus, no cases of BRONJ were reported in the trials reviewed in these systematic reviews. These reviews represent a high level of evidence and are based upon collectively large sample sizes. Two of the studies, representing results of over 26,000 osteoporotic subjects, reported no adverse events related to osteonecrosis; however, others have suggested the possibility of under-reporting of BRONJ. Walter and colleagues report a much higher incidence of BRONJ in their population, but it should be noted that these were patients with metastatic prostatic carcinoma receiving intravenous BPs (as opposeed to oral bisphosphonates, such as our patient is taking).

The systematic reviews discussed above represent a very high level of evidence. However, there is some evidence (although of a much lower level of quality and/or applicability to our patient) that suggests there is a risk of BRONJ subsequent to dental surgery. While this evidence is not as compelling, it is presented for the sake of completeness. Using PubMed, another search was undertaken using the search terms “bisphosphonate” and “jaw.” The initial search was limited to RCTs. Four citations were returned, two of which were somewhat relevant to the question. The first was a prospective trial of 7714 osteoporotic women treated with intravenous zoledronic acid. In that study, only two cases of osteonecrosis were noted, one of which occurred in a patient taking the placebo. Both cases resolved with antibiotics or debridement. This trial is significant because the study population consisted of postmenopausal osteoporotic women, rather than patients with metastic cancer. It is likely that this population is more closely related to the case-study patient’s situation. A second trial involved the use of zoledronic acid in cases of asymptomatic myeloma, which is clearly less relevant to the case-study patient. Musto and colleagues reported on results of a trial of 163 patients, of whom 81 received zoledronic acid. One case of osteonecrosis was observed, for an incidence of 1.2%. Again, however, these myeloma patients may differ in important ways from case-study patient and the results may not be applicable to osteoporotic patients.

One report raised the possibility of under-reporting of BRONJ in RCTs. Walter and colleagues carefully examined a group of 43 patients being treated with BPs for metastatic prostatic carcinoma. They reported that 18% of these patients developed BRONJ and suggest the possibility that the incidence of the condition might be under-reported. This prospective study was unique in that the subjects received careful oral examinations for evidence of dental pathology and, specifically, osteonecrotic lesions. It has been reported that adverse events are often under-reported in clinical trials. Papanikolaou and Ioannidis reviewed 1,727 systematic reviews and found that only 138 included evidence on greater than or equal to 4,000 subjects. This is the minimum sample size required for adequate power to detect an intervention-related adverse effect in 1% of subjects.

Another PubMed search was undertaken, using the search terms “bisphosphonate” and “jaw,” but without any limits. A total of 304 citations were retrieved, most of which were related to the treatment of metastatic bone cancer and were not felt to be entirely relevant to the case-study patient’s situation. One large systematic review was identified that assessed the effectiveness of alendronate in fracture prevention in osteoporotic women. These investigators reviewed 11 trials representing approximately 12,000 women. They stated that “[f]or adverse events, the authors found no statistically significant difference in any included study.” They did include the caveat that “observational data raise concerns about potential risk for upper gastrointestinal injury and, less commonly, osteonecrosis of the jaw.”

Finally, a PubMed search was conducted using the search terms “periodontal surgery” and “bisphosphonate.” Four citations were returned. One was a general narrative review in Japanese and was not deemed relevant. One described the use of a bisphosphonate in preventing bone loss in an animal model. A third was a case report of a patient who experienced a nonhealing osteonecrotic lesion following periodontal surgery in a 78-year-old woman who had taken an oral bisphosphonate for 5 years. The last was a series of 119 cases reported by Marx and colleagues and cited previously. Marx and colleagues reported the following “inciting events” in their case series: 25% were spontaneous and no precipitating event could be identified, 38% were because of removal of teeth, 29% were because of advanced periodontitis (case definition not provided), and 11% were because of periodontal surgery. As noted above, this study represents a low level of evidence, but does suggest that there may be some risk of BRONJ associated with both periodontal infection and periodontal surgery.

Collectively, this “secondary” evidence is much less impressive than the results of the large systematic reviews found in the Cochrane Library. However, given the potential serious nature of BRONJ, it seems reasonable to acknowledge the existence of this additional evidence.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses