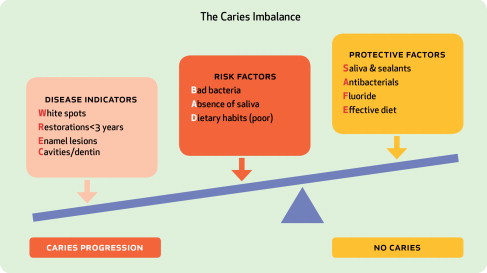

Dental caries is a dietary and host-modified biofilm disease process, transmissible early in life that, if left untreated, will cause destruction of dental hard tissues. If allowed to progress, the disease will result in the development of caries lesions on tooth surfaces, which initially are noncavitated (eg, white spots), and eventually can progress to cavitation. The “medical model,” where the etiologic disease-driving agents are balanced against protective factors, in combination with risk assessment, offers the possibility of patient-centered disease prevention and management before there is irreversible damage done to the teeth. This article discusses how to use evidence supporting risk assessment and management strategies for the caries process.

Dental caries is a dietary and host-modified biofilm disease process, transmissible early in life that, if left untreated, will cause destruction of dental hard tissues. If allowed to progress, the disease will result in the development of caries lesions on tooth surfaces, which initially are noncavitated (eg, white spots), and eventually can progress to cavitation. The “medical model,” where the etiologic disease-driving agents are balanced against protective factors, in combination with risk assessment, offers the possibility of patient-centered disease prevention and management before there is irreversible damage done to the teeth. This article discusses how to use evidence supporting risk assessment and management strategies for the caries process.

What is evidence-based dentistry?

Evidence-based dentistry (EBD) is defined by American Dental Association (ADA) as an approach to oral health care that requires clinical decision-making based on the judicious integration of systematic assessments of clinically relevant scientific evidence relating to the patient’s oral and medical condition and history; the dentist’s clinical expertise; and the patient’s treatment needs and preferences. Of the three determinants listed above, the use of current science by the clinician in the decision-making process is critical. Patients expect health professionals to keep current in their field and they rely on these professionals to think critically through available diagnostic and treatment options, to help patient’s make informed decisions about their health. On the other hand, dental treatments offered by a clinician do rely heavily on the dentist’s “clinical expertise.” However, if this is done without consideration of current available science and evidence, clinical treatment choices may be limited only to what “works well in my hands,” or on information that has been passed from one practitioner to another. The public has the reasonable expectation that a health professional has a significantly high level of current scientific knowledge in his or her field. Even with this public expectation, the movement toward evidence-based medicine is only a decade and a half old, and the movement toward evidence-based dentistry is even newer.

As logical as EBD sounds when it comes to the “medical” management of the disease of dental caries, its translation into practice has not been universally or enthusiastically embraced by all dental practitioners. There are many plausible explanations for this, but an important one to consider is that the findings of available scientific evidence may challenge and question current clinical practice. Some practitioners may sometimes struggle with the adoption of new concepts that challenge practice as they know it, even when they have strong clinical research evidence. An example of this is the fact that practitioners have been slow to adopt sealant therapy to protect susceptible pits and fissures of posterior teeth and arrest the progression of early caries lesions, despite the fact that there is very strong evidence to support their use.

That being said, we need to acknowledge that maintaining an evidence-based knowledge on every aspect of dental practice can be an overwhelming and daunting task for any dental professional. The volume of information is substantial, frequently difficult to locate, and even more difficult to separate appropriate science from unreliable information. It is frequent that the information found is contradictory and the clinician is left to decide which evidence is more credible. In addition, a large portion of the dental workforce worldwide was not trained to critically search or evaluate research findings. Thus, clinicians are uncertain how to incorporate evidence-based practice into their everyday practice model. Baelum suggested that dental schools, continuing professional education, and organized dentistry have very important roles in helping clinicians make sense of available evidence, either through educating practitioners in the techniques of EBD or in providing repositories of best practices based on sound evidence.

Levels of scientific evidence: how much is enough?

Searching the existing literature to locate the best evidence and determining the quality of the evidence available is not as difficult as translating this evidence into changes in clinical guidelines. Shekelle and colleagues developed a process for the development of guidelines that have been used within Europe and North America. This process starts with classifying evidence. Their suggested levels of evidence classification scheme, and strength of the evidence for a clinical recommendation, was based on the likelihood that evidence is susceptible to bias (eg, nature of the evidence), and thus, based on the effectiveness of studies by study design. In their scheme, the highest level of evidence is given to evidence derived from meta-analysis and systematic reviews of randomized, controlled trials (which implies that more than one trial is available on the topic), followed in a downward direction by: “evidence from at least one randomized controlled trial; evidence from at least one controlled study without randomization; evidence from at least one other type of quasi-experimental study; evidence from non-experimental descriptive studies, such as comparative studies, correlation studies, and case-control studies,” and finally to “evidence from expert committee reports or opinions or clinical experience of respected authorities, or both.”

The ultimate goal of this process is the translation of research findings into evidence-based clinical recommendations or interventions. To accomplish this, it is very important not only to look at the strength of the evidence, as described above, but also at how applicable the research finding is to the populations of interest (eg, in other words, is the evidence generalizable or applicable?). In addition, it is also necessary to determine the cost of the intervention, and the feasibility of the intervention in the context of the existing health care system. The intervention must finally be evaluated as to how it interferes or interfaces with the current beliefs and values of those who will use it (eg, how acceptable will it be to the practitioner?).

In dentistry generally, and caries management particularly, it is surprising how few studies, representing a high strength of evidence (ie, meta-analyses or systematic reviews of randomized, controlled clinical trials), exist for many of our daily intervention choices. However, limited or few apex-level evidence studies for many of the interventions that are currently available to manage dental caries does not mean that dentistry should not develop practice guidelines based on the best current evidence available for their use. If dentistry does not develop appropriate evidence-based guidelines, these interventions may be incorporated in practice in a random, disorganized and possibly incorrect manner. Recent examples of such evidence-based practice guidelines are those developed by the ADA for in-office professionally applied topical fluorides and for use of dental sealants. These guidelines are based on significant volumes of high-level research.

One of the most complete evidence-based reviews of many aspects of caries risk assessment and management was done in 2001 for the Consensus Conference on Caries Management, sponsored in the National Institutes of Health. Multiple systematic reviews were performed on caries detection and diagnosis, risk assessment, and a variety of management strategies both for adult and pediatric populations. The reviews and presentations were compiled and published in 2001 in the Journal of Dental Education , together with a summary consensus statement, and still are an excellent source for evidence-based caries management information.

Levels of scientific evidence: how much is enough?

Searching the existing literature to locate the best evidence and determining the quality of the evidence available is not as difficult as translating this evidence into changes in clinical guidelines. Shekelle and colleagues developed a process for the development of guidelines that have been used within Europe and North America. This process starts with classifying evidence. Their suggested levels of evidence classification scheme, and strength of the evidence for a clinical recommendation, was based on the likelihood that evidence is susceptible to bias (eg, nature of the evidence), and thus, based on the effectiveness of studies by study design. In their scheme, the highest level of evidence is given to evidence derived from meta-analysis and systematic reviews of randomized, controlled trials (which implies that more than one trial is available on the topic), followed in a downward direction by: “evidence from at least one randomized controlled trial; evidence from at least one controlled study without randomization; evidence from at least one other type of quasi-experimental study; evidence from non-experimental descriptive studies, such as comparative studies, correlation studies, and case-control studies,” and finally to “evidence from expert committee reports or opinions or clinical experience of respected authorities, or both.”

The ultimate goal of this process is the translation of research findings into evidence-based clinical recommendations or interventions. To accomplish this, it is very important not only to look at the strength of the evidence, as described above, but also at how applicable the research finding is to the populations of interest (eg, in other words, is the evidence generalizable or applicable?). In addition, it is also necessary to determine the cost of the intervention, and the feasibility of the intervention in the context of the existing health care system. The intervention must finally be evaluated as to how it interferes or interfaces with the current beliefs and values of those who will use it (eg, how acceptable will it be to the practitioner?).

In dentistry generally, and caries management particularly, it is surprising how few studies, representing a high strength of evidence (ie, meta-analyses or systematic reviews of randomized, controlled clinical trials), exist for many of our daily intervention choices. However, limited or few apex-level evidence studies for many of the interventions that are currently available to manage dental caries does not mean that dentistry should not develop practice guidelines based on the best current evidence available for their use. If dentistry does not develop appropriate evidence-based guidelines, these interventions may be incorporated in practice in a random, disorganized and possibly incorrect manner. Recent examples of such evidence-based practice guidelines are those developed by the ADA for in-office professionally applied topical fluorides and for use of dental sealants. These guidelines are based on significant volumes of high-level research.

One of the most complete evidence-based reviews of many aspects of caries risk assessment and management was done in 2001 for the Consensus Conference on Caries Management, sponsored in the National Institutes of Health. Multiple systematic reviews were performed on caries detection and diagnosis, risk assessment, and a variety of management strategies both for adult and pediatric populations. The reviews and presentations were compiled and published in 2001 in the Journal of Dental Education , together with a summary consensus statement, and still are an excellent source for evidence-based caries management information.

Traditional caries management: the case of minimal evidence for caries therapy

Between the years 1869 and 1915, Greene V. Black published a series of papers and texts on dental materials and preparation or restoration techniques that changed dentistry. Though many current investigators have credited or criticized these tenants for overly aggressive preparations and restorations in modern dentistry, G.V. Black was the first dentist to propose treating dental caries using minimal intervention, based on the knowledge and materials available at that time. Therefore, Black was indeed using, for his time, an evidence-based approach to dealing with the nineteenth century understanding of dental caries. During that time, the exact cause of dental caries was an unknown, cavity preparations were designed at the will of the operating dentist with no science, and dental amalgam alloy was frequently formulated by the dentist and had little standardization. These inconsistencies resulted in materials and restorations demonstrating poor performance. G.V. Black, a dentist of considerable experience and observational skills, noted the frequent failure of dental amalgam restorations with recurrent caries at the corroded margins of the restorations. Patients were observed to develop caries on virgin approximal surfaces because of the stagnation of food in these uncleansable areas. Patients were also observed to develop caries around occlusal restorations that failed to include susceptible pits and fissures. Black wrote a series of papers that addressed the problems of caries at the margins of restorations and tooth restorations. These papers represented the earliest workbooks on quality operative dentistry of that era, and these papers were based on the best knowledge available. Though not a single controlled, clinical research project was published to develop these criteria, they represented the personal observations and opinions of an expert, the lowest level of research credibility.

Black described the placement of the outer enamel margins in “self cleansable areas” so that they terminated in regions less susceptible to recurrent caries. Black wrote, “Certainly that portion near the proximate contact… is most liable to be attacked; and the liability diminishes as we recede from that point… it is to cut the enamel margins from lines that are not self cleansing to lines that are self-cleansing,” and “When a cavity has occurred in the occluding surface of a molar, the dentist prepares for filling with the idea that the fissures in this part of the enamel have favored the occurrence of the cavity. For this reason the fissures and grooves adjoining the cavity, even though not decayed, are cut away to such a point as seems to give opportunity for a smooth, even finish of the margins of the filling. This is done as a prevention of future recurrence of decay….” This led to the now infamous term “extension for prevention,” which could be summed up as “…the removal of the enamel margin by cutting from a point of greater liability to a point of lesser liability to recurrence of caries….” Furthermore, he developed an amalgam alloy less likely to corrode and suffer marginal breakdown, whose formula remained essentially unchanged until the 1970s, when high copper-silver amalgams were introduced. In addition, he developed standard and meticulous placement techniques for dental amalgam that used proper isolation. “…Restorations of cohesive gold and amalgam… require the application of the rubber dam… The student or dentist who earnestly desires to give the best service will, when in doubt, apply the rubber dam.”

This remained the state of dental education and clinical practice until the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. During this period of time, several events occurred that allowed the improvement of dental amalgams and the introduction of bonded restorations. Amalgams were improved by the development of a process whereby the amalgam alloy was triturated with the ideal quantity of mercury, known as the Eames Technique. Clinical research was performed to determine the effect that higher copper-content alloys, having less creep and marginal breakdown, had on improving the alloy longevity, but not to determine if these improvements reduced the rates of new or recurrent caries development. Clinical research demonstrated that smaller preparations displayed less material break down, but not that they were less likely to develop recurrent caries. These breakthroughs each led to changes in preparation design and restorations that were smaller and more effective, but not less likely to experience recurrent or new caries. In fact, the above studies report recurrent caries as a rationale for failure of the restoration!

The scientific advances in bonding resulted in the greatest change in operative dentistry since the publications of Black. In 1955, Buonocore described a technique for etching the enamel surface to improve retention of restorative materials and, shortly thereafter, Bowen submitted a patent entitled a “Dental filling material comprising vinyl silane treated fused silica and a binder consisting of BIS phenol and glycidyl acrylic” that enabled the restoration of a tooth with a tooth colored plastic, better known today as Bis-GMA. These two developments have resulted in the possibility of better tooth conservation or minimally invasive surgical dentistry. For example, the historic rationale for removal of an intact groove was prevention of future caries. The concern of future caries in the groove is easily dealt with by placement of a sealant, a technique well documented to prevent and arrest caries. In a sense, this is a similar concept to Black’s extension for prevention but uses the advantages of the relatively new restorative materials without the need for surgical excision and extension.

The traditional surgical method for treatment of dental caries will not eliminate the disease. In reality, the fact that the existence of recent restorations is the greatest indicator of risk for the development of new lesions only proves that the act of surgically treating the caries lesion does little to reduce the risk of developing the next lesion. Interestingly, a recent systematic review found no difference in pulpal vitality, symptoms, and longevity of restorations, irrespective of whether removal of infected tissue in a deep cavity had been minimal or complete. Therefore, evidence is challenging our current views of restorative dentistry.

Caries management by risk assessment: how much evidence is needed?

In contrast to the traditional management of dental caries based on surgical restoration of tooth damage alone, current management strategies explore treating dental caries based on an individual risk assessment of the patient (because each patient presents with their own unique set of pathologic and protective factors). Caries management by risk assessment (CAMBRA) was developed to promote the clinical management philosophy in which the caries disease process is managed following the medical model. This involves an evaluation of the etiologic and protective factors and establishment of the risk for future disease (risk assessment), followed by development of a patient-centered evidence-based caries management plan. The infectious-caries disease paradigm is based on the fact that dental caries is caused by identifiable bacterial pathogens that are part of a complex biofilm, of which mutans streptococci and lactobacilli have been extensively studied. These cariogenic bacteria thrive in acidic environments, while producing acids themselves, altering the environment to favor their own viability. These are extensively modulated by environmental changes, with a sucrose-rich diet being an important risk factor. These pathogens can colonize emerging tooth surfaces in children, transmitted for example from mother to child, as well as from tooth to tooth by improper use of the dental explorer, although the clinical implications of this latter process are less well understood.

In this disease model, carious lesions can be thought of as visible “signs” on the teeth of a chronic, potentially progressive disease process resulting from the interaction between the bacterial biofilm ecology and the conditions in the oral environment. When the active disease is diagnosed early, these bacteria can be chemotherapeutically targeted, as would any active bacterial infection in the body. The difficulty is that the pathogenic cariogenic biofilm is composed by bacteria that are part of our normal oral biofilm in an altered distribution, and not external pathogens. Thus, controlling and managing this biofilm becomes a complicated medical challenge for which more effective and less compliance-dependent treatments are still necessary for at-risk groups. If the infectious disease is allowed to progress and demineralization is not countered with remineralization, cavitations will result. Once cavitation through enamel allows bacterial to invade the dentin, minimally invasive restoration may be appropriate and necessary. The ultimate goal is to prevent and manage the disease process before tooth cavitation is allowed to occur, whereas traditional restorative methods intervene only after advanced disease destruction (cavitation) has taken place.

Appropriate CAMBRA management depends on the stage of the disease process and subsequent severity of damage to the dentition. It includes the consideration of strategies that delay and reduce the early transmission of cariogenic microflora, control the infection, prevent or remineralize the early manifestations of the disease on the teeth, and appropriately manage the more advanced stages of tooth demineralization and cavitation. CAMBRA supports the use of chemical remineralization of early pre-cavitated lesions and sealing of occlusal noncavitated lesions, along with tooth-preserving and minimally invasive restorative techniques (minimal surgical intervention) when deemed necessary in treating cavitated lesions.

The caries risk marker with the strongest evidence of correlation to future disease from the literature is still, unfortunately, past caries experience. This can be measured clinically in many ways (eg, the presence and number of noncavitated “white-spot” lesions, presence and number of recent restorations, radiographic enamel or dentin lesions, and cavitations). Many other risk factors and risk indicators have been studied in a variety of population groups, but results have been varied. However, an assessment of the caries etiologic factors (eg, plaque, diet) and protective factors (eg, exposure to fluoride, adequate salivary flow) can help inform the individualized causes for dental caries disease in a patient and help drive the development of a patient-centered, evidence-based management plan ( Fig. 1 ).