ANDREI IACOB

Chapter XV

ESTHETIC STRATEGIES IN ORTHODONTICS

15.1 CURRENT ESTHETIC CONSIDERATIONS IN ORTHODONTICS

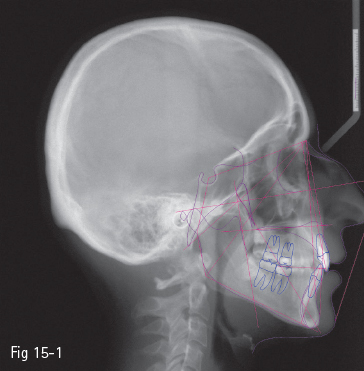

Fig 15-1 Ricketts – “E-line”.

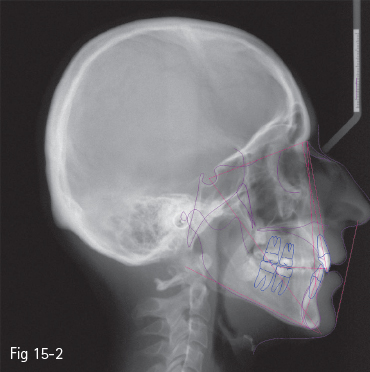

Fig 15-2 Steiner – “S-line”.

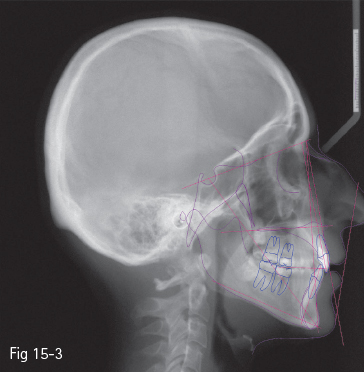

Fig 15-3 Holdaway – “H-line”.

15.1.1 Introduction

Orthodontic treatments aim at improving the patient’s quality of life. The design, implementation, and completion of the therapeutic plan should take into account the fulfillment of the following goals:1

•Improvement of facial esthetics.

•Improvement of dental esthetics.

•Achievement of a functional occlusion.

•Improvement or maintenance of periodontal health.

•Stability of the results.

•Improvement or maintenance of the quality of “airways”.

One of the main objectives of orthodontic treatment has always been an ideal dentition. Increasing consideration has recently been given to facial esthetics and the ways orthodontic treatment should be designed in order to obtain the desired esthetic effects.

The emphasis on the dental and skeletal components remains important, but increasing attention is paid to the soft tissues. In order to obtain a natural and harmonious appearance, the patient should be considered as a whole. The characteristic features of the tooth or dental segments represent only a part of a person and they cannot be considered separately.

Esthetics in orthodontics may be analyzed from the following points of view:2

•Facial esthetics.

•Dental esthetics including:

–microesthetics – the elements that make a tooth look like a tooth;

–macroesthetics – the principles that apply when groups of teeth are considered.

•Gingival esthetics.

15.1.2 Facial esthetics

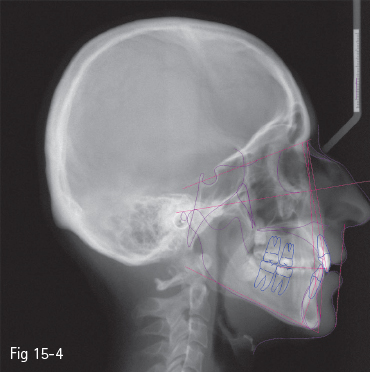

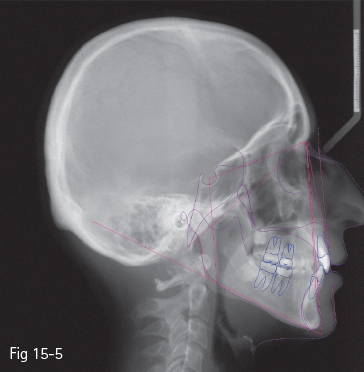

Many authors have set a series of reference points and esthetic analyses, first starting from the bone structures, and more recently with an emphasis on the soft tissues: Ricketts – “E-line” (tip of the nose to soft tissue pogonion) (Fig 15-1);3 Steiner – “S-line” (soft tissue pogonion to a point situated on the center of the curve between the nose tip and subnasale) (Fig 15-2);4 Holdaway – “H-line” (upper lip to soft tissue pogonion) (Fig 15-3);5 Burstone – “B-line” (subnasale to soft tissue pogonion) (Fig 15-4);6 Sushner – “S’-line” (soft tissue nasion to soft tissue pogonion) (Fig 15-5);7 Arnett – “soft tissue cephalometric analysis”.8,9

In order to evaluate the face, the patient should be examined both from the front and in profile, with the head in a “natural head position” and the lips relaxed. The clinical examination should include the position of centric occlusion (CO) as well as centric relation (CR), with the mouth closed to the first tooth contact. In this way, any facial alterations can be noticed that occur due to the deviation of the mandible from the CR to the CO.10

Facial esthetics analysis from the frontal view provides information on the form of the face, the symmetry, the relations between the median lines of the various structures, and the relations in the vertical plane between the face heights (Fig 15-6).10

The general form of the face may be described as round or oval, wide or narrow, short or long. Several anthropometric reference points may also be measured, such as the bizygomatic width that represents the widest facial dimension, or the bigoniac width, which should be about 30% smaller than the bizygomatic width.10

Median lines should be analyzed with the mandibular condyles centered in the glenoid fossae and at the first tooth-contact position. Without these relations, the analysis of the median lines and their relations cannot be assessed correctly. According to Arnett,10 the midline of the face should be taken to be the line that passes through the points marking the center of the upper lip filtrum and the center of the nose bridge and a point situated at the mid-distance between the inner corner of the eyes (Fig 15-6).

Fig 15-4 Burstone – “B-line”.

Fig 15-5 Sushner – “S’-line”.

An esthetically attractive face is divided into three equal heights by horizontal lines going through the brows line, subnasale, and soft tissue menton. Deviations from these norms will be represented by the increase or the decrease of one or more heights (Fig 15-6).10

Studies have shown that in reality the face heights are rarely equal, and for facial esthetics it is more important to have a vertically good relation between the elements composing the lower part of the face. The lower height is placed between the subnasale and soft tissue menton anthropometric points. This level includes three components: the upper lip, the interlabial gap, and the lower lip. The lips should be assessed separately, in rest position. The length of the upper lip, measured between the subnasale and stomion anthropometric points, is 19 to 22 mm, with higher values in men and in the elderly. The space between the relaxed lips is 1 to 5 mm. Statistically, larger spaces have been recorded in women as compared to men. The lower lip is measured between the lower stomion and soft tissue menton anthropometric points, ranging from 42 to 48 mm and increasing with age, probably due to the accumulation of adipose tissue in the submental area. The normal ratio between the upper and lower lip dimensions is 1:2.2. Well-proportioned lips are in harmony regardless of their length.10

Fig 15-6 The clinical facial examination – frontal view.

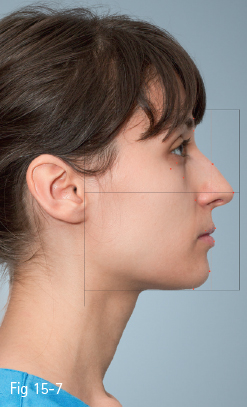

Fig 15-7 The clinical facial examination – profile view.

In addition to the data provided by the relaxed lip position, the facial aspect is also analyzed in closed-lip position. This position may evidence possible dimensional imbalance between the skeletal and the soft tissue structures. If the soft and bony structures are well balanced, the lips may close from the rest position without tension in the mentalis, alar, or the orbicular muscles. The size of the lips is an important factor in facial esthetics. The red of the upper lip has values between 6 to 9 mm, and that of the lower lip between 8 to 12 mm. A correct ratio between the lips is when the red of the upper lip is 2 to 3 mm smaller than the lower one.10

The patient’s profile is clinically assessed with the patient seated in “the natural head position“, the mandible centered in CR, the lips at rest, and the mouth closed to the first tooth contact. If necessary, and in order to obtain this position, occlusion waxes will be used.10

According to Arnett, in the profile analysis (Fig 15-7) the face may be divided into three components: the mandibular area, the maxillary area, and the high midface.10

In the high midface, four soft tissue elements are analyzed: the soft tissue glabella, the soft tissue orbital rim, the soft tissue cheekbone, and the subpupil area (Fig 15-7).

The maxillary area includes four soft tissue elements: nasal base, position of the upper lip, the supporting tissues of the upper lip, and the nasal projection (Fig 15-7).

The mandibular area includes the position and prominence of the lower lip, the soft tissue pogonion projection, the length and contour of the throat, and the relation in sagittal plane between the maxillary and mandibular incisors: the overjet. In this area, the profile projection, the projection of the chin, and the amount of adipose tissue in the submental zone should be analyzed (Fig 15-7). According to Arnett, the analysis of the overjet is part of the examination of the mandibular profile, the normal value being between 0 and 3 mm. The analysis of the overjet will be repeated in the intraoral examination, and will be also analyzed using cephalometrics.10

15.1.3 Dental esthetics

The dynamic relation between the teeth and the surrounding soft tissues, during and after orthodontic treatment, as well as the facial features of the patient are very important and must be analyzed. The amount and shape of the dental crown that will be exposed during the lip movements should agree with the age, gender, and facial traits of the patient.

The purpose of the analysis is to obtain some guidelines on the assessment of the esthetic characteristics and the adequate dimension, vertical and transverse, of both static and dynamic tooth display.2

Based on the principles of visual perception and their clinical application in dentofacial esthetics, it has been evidenced that an accurate analysis of dental esthetics requires the examination of the patient’s facial expression from the front, at rest and during function.12

Information such as the alignment of midlines, or the right-left symmetry of canines and premolars, can only be obtained if the patient is observed from the frontal view.2,12 From this perspective, the orthodontist should analyze the following parameters:2,13

• Length of the maxillary and mandibular incisors’ crowns.

• Contour of the incisal margins before and after the recontouring of these incisal margins.

• Position and symmetry of the gingival margins of the maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth.

• Axial inclinations of all anterior teeth.

• Midlines.

• Contact areas between teeth (the place where teeth touch).

• The symmetry and torque of canines and premolars (labiolingual inclination of these teeth).

• The harmonious curved display of the teeth, from the anterior to the posterior teeth.

If the patient’s examination is performed with the esthetic objectives in mind, especially in the context of the multidisciplinary approach, it should start with the analysis of the position of the maxillary incisors in relation to the upper and lower lips. The assessment should be performed with the lips at rest and during smile.8,9,10,14

The most valuable esthetic information in treatment planning is obtained by observing the patient during a normal conversation. The visibility of the teeth during smile also provides valuable information, as the upper lip is raised. With age, the soft tissues lose their tone and elasticity, the upper lip drops and covers more of the maxillary incisor, while the lower lip descends and uncovers more of the mandibular incisor.2,15,16

In this context, the position of the maxillary incisors may be considered acceptable or unacceptable (Figs 15-8 and 15-9). An acceptable level of exposure of the maxillary incisors at rest depends on the patient’s age. Studies show that the more advanced the age, the less the maxillary incisors will be exposed by the upper lip. This is one of the reasons a gummy smile is more frequently seen in young people. Thus, if at the age of 30 the level of exposure of the incisors is 3 to 4 mm, it may decrease to only 1 mm at the age of 60. The decrease may be caused by the poor muscular tone of the upper lip.2,14,17,18

Various other studies have reported age-induced alterations to the lips. In a study by Peck et al,19 the exposure of maxillary incisors with the upper lip at rest is 4.7 mm in boys and 5.3 mm in girls at the age of 15 years. Another representative study by Vig and Brundo18 demonstrated that the decrease of the maxillary incisor exposure is accompanied by increased mandibular incisor exposure with age.

Fig 15-8 Insufficient exposure of the maxillary incisors.

Fig 15-9 Overexposure of the maxillary incisors.

If the exposure of the maxillary incisors is considered inadequate, the main objective of a multidisciplinary treatment would be to correct this by restorative methods, dental prosthetics, orthodontic extrusion, or intrusion and orthognathic surgery.14,20

In orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics, the current therapeutic tendencies for overbite have changed as a result of the importance attributed to the exposure of the maxillary incisors, both at rest and during function.2,20,21

In the past, the emphasis was on the mandatory opening of the bite by the intrusion of the incisors and/or the extrusion of the molars. Nowadays, the exposure of a small area of the gingival margin during smile (up to 2 mm) is acceptable, as long as the visibility of the incisors at rest is adequate, and the resulting overbite and overjet at the end of the treatment ensure a correct functional occlusion.2,22,23

The various methods of intrusion used in orthodontics, such as special intrusion arches, overlay arches, etc, may determine an exaggerated intrusion, the maxillary incisors being completely covered by the upper lip at rest at the finish of orthodontic treatment, a condition aggravated by age.2,23

The relation between the position of the incisors and the lip must be constantly monitored during the orthodontic treatment. During this monitoring period, it should be decided whether orthodontic intrusion is necessary or not, or whether a mixed therapy is necessary, consisting of incisor intrusion and crown lengthening by restorative methods (direct restoration) or by prosthetics (indirect restoration).2,22,23

Usually, overbite is due to a marked curve of Spee, in which the six anterior mandibular teeth are above the functional occlusion plane. In these cases, the correct therapeutic solution is the intrusion of the mandibular teeth by intrusion arches.2,22

An alternative to the incisors’ intrusion for overbite in children may be the extrusion of the molars. This effect may be obtained with various orthodontic appliances: functional appliances, bite plates that ensure the disocclusion of the molar zone, and extraoral appliances such as facebows.2,24 It is important to bear in mind that molar extrusion should be limited to children with a vertical, or preferably counterclockwise, facial pattern, and avoided in those with a clockwise pattern. Molar extrusion is not indicated in adults because of the lack of stability, as well as the high patient compliance requirements and esthetic impairment, both representing difficulties for this age group.2,25,26

The upper dental midline is assessed in relation to the upper lip filtrum, the middle of which is one of the most symmetrical points for soft tissues. Most patients use this point as a reference in appreciating the upper interincisor line at the end of orthodontic or orthosurgical treatment (Fig 15-10).10

The coincidence, or its absence, between the upper and lower interincisor lines is another factor to be analyzed in dental and facial esthetics (Figs 15-11 and 15-12). In some cases, there is no coincidence between these lines due to various causes: skeletal asymmetries, discrepancies in size between inter-/intradental arches, edentulous spaces altering the arch symmetry, morphologically or dimensionally inadequate dental restorations.

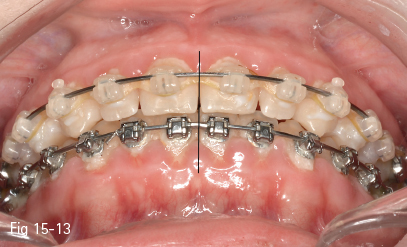

The impact of this discrepancy on dental esthetics is actually less than it was initially thought (Figs 15-13 and 15-14). Some studies27,28 analyzed the perception of the deviation of the interincisor line in three observer groups composed of orthodontists, general dental practitioners, and persons without dental training. The results showed that neither general dentists nor those without dental training noticed any difference up to a deviation of 4 mm, as long as the long axis of the teeth was parallel with the vertical axis of the face. Both orthodontists and the two other groups considered that a deviation up to 4 mm of the interincisor lines does not impact on facial esthetics.

An important effect in dental esthetics is the parallelism of the long axis of the maxillary incisors (Fig 15-15). Research has demonstrated that a 2 mm inclination of the long axis of these teeth is considered unpleasant.14,27,29 The correction of the axis may be performed by orthodontic or prosthetic methods, according to the restoration required for these teeth.

The same considerations regarding the position, symmetry, slant, and exposure of the incisors should be given to the mandibular teeth. The mandibular incisors should be related to the position of the maxillary ones to ensure optimal functional and esthetic interactions between them. The exposure and positioning of the mandibular incisors will be included in the treatment plan and performed by orthodontics, restorative procedures, prosthetics, implants, or orthognathic surgery.14,30,31

The orthodontist should be aware of the fact that dental esthetics and the functional occlusion are in a mutual relationship. The two concepts, esthetics and function, cannot exist without one another. The most successful, natural-looking dental esthetics is the result of the integration of the existing relations between the morphological and functional details.32

Fig 15-10 Upper midline correctly centered in relation to the upper lip at the end of the orthodontic treatment.

Fig 15-11 Midline deviation before the orthodontic treatment.

Fig 15-12 Centered midlines in the same patient at the end of the orthodontic treatment.

Fig 15-13 Correctly centered midlines at the end of the orthodontic treatment.

Fig 15-14 Midline discrepancy at the end of the orthodontic treatment.

Fig 15-15 Lack of parallelism shows a discrepancy between the tooth axes and the facial midline.

Fig 15-16 Uneven free gingival margins and gingival recessions.

In this context, we should bear in mind that after establishing the ideal position of the incisal margins, the orthodontist should position the level of the posterior occlusal plane in relation to this position. The correction of the posterior occlusal plane may be performed by orthodontics, prosthetics, or orthognathic surgery. The size and morphology of the crowns, their modifications by wear or different types of restorations, the patient’s facial pattern, the amount and position of the alveolar bone, and the relation established by the posterior teeth with the lower lip during smile are all factors that will influence the choice of the therapeutic modalities for setting the level of the occlusion plane in the posterior area, as indicated by each clinical case.14,33,34

15.1.4 Gingival esthetics

Problems with gingival esthetics may be due to the exaggerated or uneven exposure of the free gingival margins, and also to local or general gingival recessions that occur following bone tissue loss.35

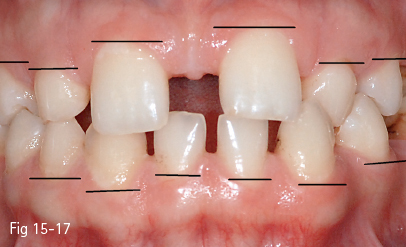

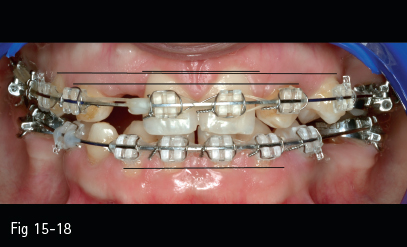

The level of the free gingival margins is determined by the axial cant and the alignment of the teeth (Fig 15-16). The correct positioning of the teeth on the dentoalveolar arch will level the gingival margins and improve gingival topography (Figs 15-17 and 15-18).11

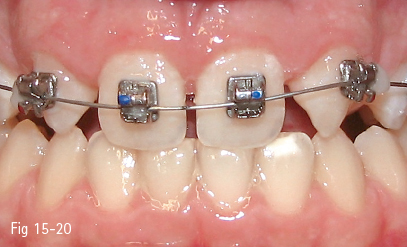

A difficult instance from the point of view of dentogingival esthetics is encountered in cases of maxillary lateral incisor anodontia, when the space is closed by the substitution of the lateral incisor by the canine. The leveling of the gingival margins is necessary in these cases in order to obtain the best gingival esthetics and avoid the unesthetic appearance of the canine protuberance in the substitution area (Fig 15-19).35,36 The dentogingival esthetic objectives to be taken into consideration are:

• The contours of the gingival margins of the maxillary central incisor and maxillary canine should be above the contours of the maxillary lateral incisor.36,37

Fig 15-17 Uneven free gingival margins before the orthodontic treatment.

Fig 15-18 Leveling of the free gingival margins by orthodontic treatment in the same patient.

Fig 15-19 Clinical view of lateral incisor anodontia.

Fig 15-20 Individualized bonding of the brackets in lateral incisor anodontia: mandibular premolar brackets, for torque correction, may be seen bonded on the maxillary canines that will substitute the lateral incisors.

• The long axes of the crowns of the maxillary central incisors and canines should be situated mesial to the gingival zenith.36,37

• The long axis of the maxillary lateral incisor crown should pass through the gingival zenith.36,37

• The proportions of tooth sizes: the tooth width should be about 60% to 70% of its length.36,38

The therapeutic strategies should include the individualization of the bonding of the brackets on the teeth in order to make it possible (Fig 15-20):36

• The slight extrusion and tipping of the long crown axis of the maxillary canine replacing the lateral incisor in relation to the gingival zenith.

• The application of a positive torque on the maxillary canine replacing the lateral incisor in order to improve the emergence profile and the protruding aspect of the canine fossa.

• The intrusion of the first maxillary premolar in order to mimic the position of a maxillary canine in relation to the free gingival margin.

• The adjustment of the dental proportions according to the requirements, by restorative or prosthetic methods, in agreement with the general dentist.

It is important that orthodontic treatment maintains and provides an aligned and esthetic gingival contour. Therefore, we must take into consideration the fact that when patients have one or several teeth with fractured, chipped, or worn out crowns, the lengthening of the clinical crown by orthodontic extrusion may determine an unpleasant aspect as a result of the altered gingival contour. In such cases, the correct therapeutic management consists of the direct or indirect restoration of the affected teeth, after the orthodontic leveling of the gingival contour.35

If the orthodontic treatment of teenagers should take into account the alignment of the marginal crests and cusps, in adults the correct leveling of the gingival contour should be ensured, ie, the leveling of the interproximal alveolar bony crests along the dentoalveolar arch.11

Gingival esthetics may be greatly improved by the beneficial effects at the level of the bone and soft tissues, which are obtained by the dental movements during orthodontic treatment. Orthodontic treatment may lead to improved prognosis of periodontal disease and, in some cases, the minimization of the indication or extent of periodontal surgery.11

The application of brackets on the various teeth will be performed according to the individual in order to obtain the alignment of the alveolar crests and free gingival margins, without taking into account the bonding reference marks specific to various bracket systems. A change to the bonding height of the brackets on the teeth with respect to the free gingival margin will require an occlusal adjustment equilibration through selective grinding of these teeth during the stage of orthodontic alignment and leveling.11 These reductive coronoplasty procedures will also provide a better crown/root relation for the teeth affected by periodontal bone loss.39

Certain vertical periodontal defects may be minimized or eliminated by controlled dental extrusions using light forces (orthodontic eruption) that will stimulate bone formation without loss of gingival attachment in these teeth, thus improving the level of alveolar bone and contributing to the overall improvement of gingival esthetics.40

This type of slow orthodontic extrusion may be used in cases with important vertical periodontal defects of the maxillary anterior teeth, in which the marked bone resorption associated with gingival recessions and ample dental migration prevents an adequate esthetic restoration. In these situations, the bone level may be augmented by apposition of new alveolar bone, while the soft tissue position may be corrected by increasing the level of the attached keratinized gingiva by slow orthodontic extrusions (0.5 to 1 mm extrusion per month, followed by a month of rest). This technique includes the reduction of the crown length of the extruded tooth and, in some cases, even the endodontic treatment of the tooth. At the end of the procedure, clinical condition permitting, the tooth may be kept or replaced by an implant, this time in a favorable implant site.41–45

In the context of bone formation by orthodontic-forced eruption, before the orthodontic treatment is initiated, specific periodontal procedures should be performed to ensure eradication of local infection and inflammation, and, if necessary, procedures of guided tissue regeneration should also be performed. Only in these conditions will the orthodontic-forced eruption take effect on bone regeneration, and result in an increase of the width of the attached keratinized gingiva, and even have an effect on the osteointegration of the materials used for tissue regeneration.46

The topography of the bone loss defect in relation to the direction of the orthodontic tooth movement plays an important role. The orthodontic movement of the tooth away from the bone loss defect may have positive effects on bone regeneration due to traction forces applied in the bone loss defect area, while the orthodontic movement of the tooth toward the bone loss defect may, at best, determine the maintenance of alveolar bone level, or even a worsening of the periodontal defect due to pressure forces applied in the area of the bone loss defect.46

An important component of gingival esthetics is ensured by the presence, size, and position of the interdental papillae. The normal dimension of the gingival tissues above the proximal alveolar bone ridge is 4.5 mm. Studies have shown that the optimal ratio between the size of the papillae and the crown length of the maxillary central incisors is 1:2.47,48

An important gingival esthetics problem is represented by the orthodontic alignment of teeth in the presence of periodontal defects and gingival recessions, which will lead to the appearance of the so-called “black triangles” in the proximal spaces. This creates an unesthetic appearance, especially in the maxillary anterior area. One way to solve this esthetic problem is to remove a small amount of interproximal enamel in order to facilitate tooth contact. Another approach moves the teeth contact points towards the cervical, thus diminishing the spaces for the interproximal papillae. This approach is more efficient in the case of trapezoidal incisors, which allow more interproximal reduction.34,48

15.1.5 Smile esthetics

The relationship between gingival, dental, and facial esthetics is best understood in the esthetic analysis of the smile. An accomplished smile esthetic is obtained when the anterior teeth are in harmony with the guidelines of occlusion and stability. It should be taken into account that the position of the incisal margins determines the angle of the anterior guidance and that good positioning of the incisors affects both dental and facial esthetics, as well as the occlusal function and the case stability.32

The smile line is defined as the relation between the inner contour of the lower lip and the incisal margins of the maxillary incisors. It may be of three types: parallel, straight, or reversed. Studies have reported that 85% of the population have the incisal margins parallel with the lower lip, in 14% the incisal margins are straight, and only in 1% are the incisal margins reversed. To sum up, the objective of esthetic rehabilitation is to achieve a contour of the incisal margins that is parallel with the lower lip. A reversed contour is often associated with marked wear of the maxillary incisors. There is also a gender dysmorphism, the smile line in men being lower than in women.2,18,49

The types of smile may be analyzed from the point of view of the amount of exposure of the incisors and the gingival margins. The coverage of the incisors by the upper lip classifies the smile into several types: smiles with little exposure, average exposure, and large exposure of the maxillary incisors.2

The most frequent smile type is an average exposure of the maxillary incisors (about 70% of young adults), in which 75% to 100% of the upper incisors’ surface is exposed. In 20% of the population, the exposure is less than 75% of the incisors’ surface, while the smile that exposes the whole surface plus a small portion of the gingiva, ie, the gummy smile, is seen in 10% of the population.

The number of teeth exposed in the smile is another factor in smile and dentofacial esthetics. In young adults, the smile reveals the six anterior teeth and the first or second premolar; only in 4% of cases does the smile reveal the first molar.49

The gummy smile is defined as the exposure of 2 mm or more of the gingival margin when smiling. The issue of gingival exposure during the smile has been a subject of huge debate between orthodontists for a long time. The etiology of the gummy smile may be considered the result of the combined effects of an anterior vertical maxillary excess and the increased muscular capacity to raise the upper lip during smile, as well a number of other factors, such as a greater mouth opening at rest, and excessive overbite and overjet.2,50 Surprisingly, the length of the upper lip, or the length of the central incisor, and the angles of the mandibular and palatal planes are not related to the etiology of the gummy smile.51

The treatment of patients with a gummy smile usually includes combined orthodontics, periodontics, and surgical methods. The differential diagnosis should consider the visibility of the incisors at rest and of the gingival margins when smiling. If at rest the exposure of the incisors is good, their intrusion is not necessary, but the lengthening of their crowns by the means of gingivoalveoloplasty is indicated in order to reduce the visible gum.52,53 When the alveolar ridge is reduced for surgical lengthening of the clinical crown, the gingival margins will stabilize at about 3 mm from the new alveolar bone level within six months.54

More drastic therapy of the gummy smile may require orthognathic surgery that repositions the maxillary jaw (Le Fort I osteotomy) and the reduction of the excessive maxillary height.51

The pleasant appearance of the smile depends very much on the incisor crown torque. This is due to the way light is reflected on the buccal surface of the tooth. In people with correct crown-root torque and interincisal angle, the smile is more pleasant than in people with a wide interincisal angle and with incisors with a negative crown torque.2

A number of studies analyzing the transversal dimension of the smile have evidenced that the fullness of a smile depends on the correct torque of the maxillary canines and premolars, as well as their shape within the different facial types, rather than on non-extraction therapies or arch expansion, leading to an exaggerated dental tipping.2

The most important elements on which the transversal dimension of the smile depends are:2

• Labiolingual crown inclination of the terminal tooth in each quadrant that shows when smiling.

• Symmetry of the crown inclination of the contralateral teeth.

• Harmony of the front-to-back tooth display curve.

• Relation between the size of the maxillary apical base and the labiolingual crown torque of the maxillary teeth.

• Presence or absence of buccal corridors.

Numerous studies that have been done have reported on the perception of buccal corridors,2,55–58 and none have evidenced a relationship between them and smile esthetics. The presence of these negative spaces is considered to be a feature that makes the smile more natural. Apparently, the labiolingual crown torque of the canines and premolars is equally or more important than the dark areas of the buccal corridors for the fullness of the smile.

If, at the beginning of the orthodontic therapy, there is a dark space between the mouth corners and the maxillary dental arch, but the maxillary dental arch is acceptable in shape and width, then we should consider deliberately torqueing the crowns in a buccal direction in order to minimize the dark space (Fig 15-21). The transversal expansion of the maxillary jaw is indicated only when it is considered too narrow in relation to the mandibular jaw.2

The maxillary teeth labiolingual crown torque varies greatly from one patient to another. There are patients with wide maxillary arches and teeth lingually inclined, as there are patients with narrow arches and teeth buccally inclined.2 Due to these characteristic features, the orthodontic treatment should be personalized for each patient for optimal esthetic results.

15.1.6 Extractions in orthodontics and esthetics

Extraction versus nonextraction is probably the oldest and most wrenching debate in orthodontics. This debate began with Case and Angle, but it is still topical nowadays.

The advocates of nonextraction therapy argue that extractions can induce facial decline, while keeping all the teeth in the arch will automatically produce an adaptation of the soft tissue and bone, which will lead to a more harmonious and esthetic appearance.59

Choosing an option of treatment with extraction or nonextraction should be the result of a thorough diagnosis that takes into account the treatment objectives of optimum dental and facial esthetics, functional occlusion, periodontal health, and stability.59

The orthodontist should analyze each clinical case to decide whether the esthetic and functional goals can be accomplished keeping all the teeth in the arch. If it is possible to do so, then extractions should not be considered. In many instances, however, extractions are necessary to improve the patient’s esthetic appearance and to achieve a solid, functional occlusion.

Even if there is a common belief that extractions are detrimental to facial esthetics, the studies and the orthodontic literature do not support this belief.

The following is said in an article by Bishara and Jakobsen: “The extraction/nonextraction decision, if based on sound diagnostic criteria, does not have a systematic detrimental effect on the facial profile.”60

In another article comparing the esthetic results of profiles of patients treated with both extraction and nonextraction therapy, Luppanapornlarp and Johnston came to the conclusion that premolar extractions do not cause “dished-in” profiles and that “it was the nonextraction patients who tended to have more concave faces, whereas the extraction patients more often had what nonextraction advocates might call a nice full pleasing profile”.61

Another misconception is that extractions could have a detrimental result regarding facial and dental esthetics by altering the arch width and the teeth exposure, and worsening the patient’s smile by creating large buccal corridors. Again, this idea it is not supported by the literature.2 In his chapter entitled Esthetics in Tooth Display and Smile Design, Zachrisson says:

Fig 15-21 Marked inward inclination of the dental axes, which make possible the reduction of the buccal corridors by inclining the teeth in buccal direction.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses