Conventional endodontic therapy is successful approximately 80–85% of the time. Many of these failures will occur after one year. The presence of continued pain, drainage, mobility or an increasing size of a radiolucent area are some of the indications to treat the case surgically. Since many of these cases may have had final restorations placed by the dentist, the salvage of these cases is of importance to the patient. Advances in periapical surgery have included the use of ultrasonic root end preparation. With the use of these piezoelectric devices, a more controlled apical preparation can be achieved. Additionally, isthmus areas between canals can be appropriately prepared and sealed. The precision afforded with these devices reduces the chances for a malpositioned fill and a more successful outcome.

Preoperative planning

Although endodontic care is typically successful, in approximately 10% to 15% of cases symptoms can persist or spontaneously reoccur. Many endodontic failures are caused by the failure to place an adequate coronal seal. Therefore there is the competing interest of observing the tooth after endodontic treatment to ascertain successful treatment versus placing a definitive restoration. Many endodontic failures occur a year or more after the initial root canal treatment, often creating a situation in which a definitive restoration has already been placed. This situation creates a higher value for the tooth because it now may be supporting a fixed partial denture. A decision is then needed to determine if orthograde endodontic retreatment can be accomplished, should periapical surgery be recommended or consideration of extraction of the tooth with loss of the overlying prosthesis.

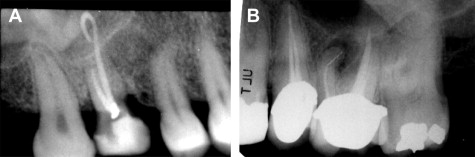

Causes of endodontic failures can often be separated into biologic issues such as a persistent infection or technical factors such as a broken instrument in the root canal system ( Fig. 1 ), transportation of the apex, perforation, and ledging of the canal. Failure of endodontic treatment is most commonly caused by lack of an adequate coronal seal, with the presence of bacteria within the root canal system and apical leakage. Continued infection may also result from debris displaced outside the apex during the initial endodontic treatment. Technical factors alone are a less common indication for surgery, comprising only 3% of the total cases referred for surgery, yet it is this author’s opinion that there is a higher success rate in these cases.

Before surgery, discussions with patients are critical in order for the patient to give appropriate informed consent. The particular risks of surgery based on the anatomic location (sinus involvement or proximity to the inferior alveolar nerve) need to be reviewed and documented. It is important to stress the exploratory nature of periapical surgery to the patient. Depending on the findings at surgery, a limited root resection with retrograde restoration may be placed. However, the patient and surgeon must also be prepared to treat fractures of the root or the entire tooth. Plans must be made preoperatively on how such situations will be handled should they be noted intraoperatively.

Surgical endodontics success rates have dramatically improved over the years with the developments of newer retrofilling materials and the use of the ultrasonic preparation. Previously cited success rates of 60% to 70% have now increased to more than 90% in many studies, because of the routine use of ultrasonic retrograde preparation and the use of mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) as a filling material. This significant improvement makes apical surgery a more predictable and valuable adjunct in the treatment of symptomatic teeth. Most significantly, studies show once the periapical bony defect is considered healed (reformation of the lamina dura or the case has healed by scar) the long-term prognosis is excellent. These studies reported 91.5% of healed cases still successful after a follow-up period of 5 to 7 years. Therefore with adequate radiographic follow-up the surgeon should be able to predict the long-term viability of the tooth and its usefulness to retain a prosthetic restoration.

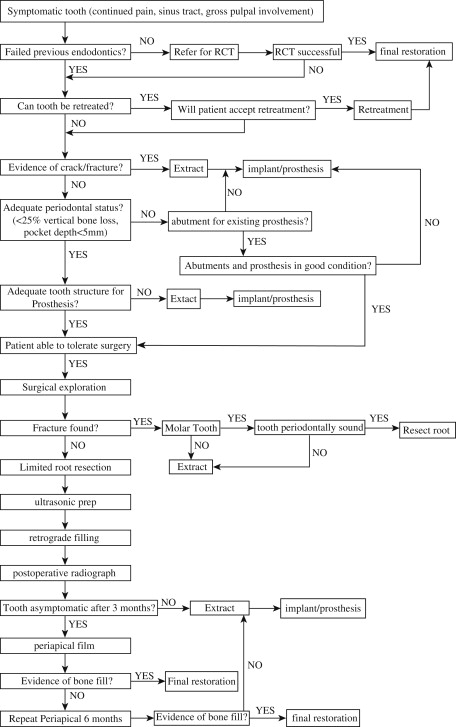

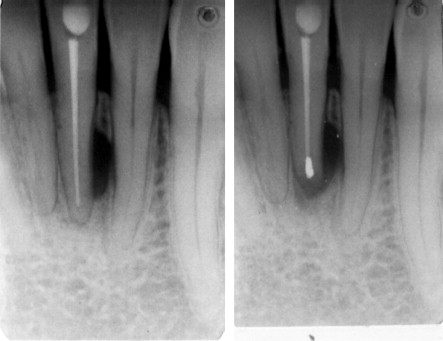

The primary option for the treatment of symptomatic endodontically treated teeth is that of conventional retreatment versus the surgical approach. An algorithm for a decision regarding retreatment versus surgery versus extraction is presented in Fig. 2 . In discussions with patients the option of conventional retreatment should be discussed. However, clinical studies have not shown retreatment to be more successful than surgery, and 1 prospective study found surgical treatment to have a higher success rate. Although endodontic retreatment seems more conservative, the removal of posts, reinstrumentation of the tooth, and removal of tooth structure increase the chance of fracture. Surgical treatment of failures also provides the opportunity to retrieve tissue for histologic examination to rule out a noninfectious cause of a lesion ( Fig. 3 ).

The option of extraction with either immediate or delayed implant placement must also be discussed as an alternative to periapical surgery. There is no debate in dentistry that implants can outlast tooth-supported restorations. It is valuable therefore to have data to predict the expected success of the endodontic surgery so the patient can use that in their decision-making process. Factors that improve success are noted in Box 1 . In cases of an expected poorer success rate such as the presence of severe periodontal bone loss (especially the presence of furcation involvement), the decision to extract the tooth and place an implant may be a more efficacious and clinically predictable procedure.

SUCCESS:

-

Preoperative factors

- 1.

Dense orthograde fill

- 2.

Healthy periodontal status

- a.

no dehiscence

- b.

adequate crown/root ratio

- a.

- 3.

Radiolucent defect isolated to apical one-third of tooth

- 4.

Tooth treated

- a.

Maxillary incisor

- b.

Mesiobuccal root of maxillary molars

- a.

-

Postoperative factors

- 5.

Radiographic evidence of bone fill after surgery

- 6.

Resolution of pain and symptoms

- 7.

Absence of sinus tract

- 8.

Decrease in tooth mobility

FAILURE:

-

Preoperative factors

- 1.

Clinical or radiographic evidence of fracture

- 2.

Poor or lack of orthograde filling

- 3.

Marginal leakage of crown or post

- 4.

Poor preoperative periodontal condition (furcation involvement)

- 5.

Radiographic evidence of post perforation

- 6.

Tooth treated

- a.

Mandibular incisor

- a.

-

Postoperative factors

- 7.

Lack of bone repair after surgery

- 8.

Lack of resolution of pain

- 9.

Fistula does not resolve or returns

There is a body of literature that supports the duration of restorations fabricated on endodontically treated teeth. Basten and colleagues reported a 92% 12-year survival rate, and Blomlof and Jansson found surgically treated molars with healthy periodontal status had a 10-year survival rate of 89%. The factors most associated with failures are long posts in teeth with little remaining coronal structure. Thus, the condemnation of a tooth because it can be replaced with an implant is not clear.

An economic analysis may be indicated to guide the patient’s decision. If the case has a final prosthetic restoration already in place it is usually easier to recommend surgical intervention. If the symptoms do not resolve the patient has only expended the additional time, operative risk, and expense of the surgical portion of their care because they have already have a definitive restoration. The surgeon should review the factors in Box 1 to help predict the likelihood of the surgical intervention being successful. If the tooth has multiple factors that indicate the success of the surgical intervention would be compromised or the tooth has a poor expectation for 10-year survival, then extraction with implant placement is a more efficacious means of care.

The surgeon may be called on to treat teeth that cannot be negotiated for conventional orthograde endodontics. The treatment of teeth with calcified canals may be appropriately managed with apical surgery alone with a retrograde filling if the tooth is critical to a restorative treatment plan. Danin and colleagues showed at least a 50% rate of complete radiographic healing and only 1 failure in 10 cases over a 1-year observation period in cases treated surgically only and without endodontic treatment. Bacteria still remained in the canals of the tooth in 90% of these cases, which may lead to a later failure.

Determination of success

More complicated decisions are involved with teeth that have not been definitively restored. In that situation not only does the surgeon have to consider the preoperative potential for the apical surgery to be successful, but often must determine when the case is deemed successful and the case can proceed to the final restoration. Once a final restoration is placed, considerable more time and expense have been invested and subsequent failure is more troublesome to the patient.

Rud and colleagues retrospectively reviewed radiographs after apical surgery to determine radiographic signs of success. Their work showed that with a retrospective review of cases more than at least 4 years after surgery, once radiographic evidence of bone fill occurs (noted as successful healing in their classification scheme), the tooth was stable throughout the remainder of their study period (up to 15 years). A waiting period of more than 4 years is not acceptable in contemporary practice, but these investigators’ classification scheme has been validated over shorter observation times. They found that if radiographic evidence of bone fill of the surgical defect is noted, then the tooth remained a radiographic success over their observation periods. Many of the partially healing cases, noted as “incomplete healing” in their study, tended to move into the complete healing group during the 2 years after surgery, with few changes throughout the next 4 years of observation.

An appropriate follow-up protocol is to obtain a repeat periapical film 3 months after surgery, with critical comparison with the immediate postoperative film. If significant bone fill has occurred, mobility has decreased, pain is resolved, and no fistula is present, the case can proceed to the final restoration. However, if significant bone fill has not been noted, the patient should be recalled again at 3 months for a new film. Rubinstein and Kim found complete healing in 25.3% of cases in 3 months, 34% took 6 months, 15.4% 9 months, and 25.3% 12 months. Small bony defects healed faster than large, which showed significant differences in their prospective study. In contrast any increase in the size of the radiolucency or no improvement should caution the dentist about making a final restoration. If the situation is not clear at that time (6 months postsurgically) a temporary restoration, loaded for a least 3 months, is often a good litmus test of the success of the surgery and predictive as to whether the final restoration will last for some time.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses