Introduction

Anterior open bite results from the combined influences of skeletal, dental, functional, and habitual factors. The long-term stability of anterior open bite corrected with absolute anchorage has not been thoroughly investigated. The purpose of this study was to examine the long-term stability of anterior open-bite correction with intrusion of the maxillary posterior teeth.

Methods

Nine adults with anterior open bite were treated by intrusion of the maxillary posterior teeth. Lateral cephalographs were taken immediately before and after treatment, 1 year posttreatment, and 3 years posttreatment to evaluate the postintrusion stability of the maxillary posterior teeth.

Results

On average, the maxillary first molars were intruded by 2.39 mm ( P <0.01) during treatment and erupted by 0.45 mm ( P <0.05) at the 3-year follow-up, for a relapse rate of 22.88%. Eighty percent of the total relapse of the intruded maxillary first molars occurred during the first year of retention. Incisal overbite increased by a mean of 5.56 mm ( P <0.001) during treatment and decreased by a mean of 1.20 mm ( P <0.05) by the end of the 3-year follow-up period, for a relapse rate of 17.00%. Incisal overbite significantly relapsed during the first year of retention ( P <0.05) but did not exhibit significant recurrence between the 1-year and 3-year follow-ups.

Conclusions

Most relapse occurred during the first year of retention. Thus, it is reasonable to conclude that the application of an appropriate retention method during this period clearly enhances the long-term stability of the treatment.

Editor’s comment

We can expect to achieve long-term success in the closure of anterior open bites 75% of the time by treating this malocclusion with fixed appliances, with either a nonsurgical or surgical approach, depending on the overall skeletal and esthetic demands of the case. But for some patients, neither option is ideal. A nonsurgical approach often requires full-time use of elastics to close the open bite by extruding the anterior teeth. This type of tooth movement demands excellent cooperation, might not enhance facial esthetics, and could also be unstable. When considering the other choice, to many people, “surgery” is still “surgery” and might be rejected for any number of reasons. With good studies to support what can and cannot be achieved in the treatment of malocclusions characterized by anterior open bite, there is still room for a third option—treatment with miniscrew implants to intrude the maxillary posterior teeth. Several questions then come to mind. How far can the maxillary posterior teeth be safely intruded? Will this approach lead to increased stability? If immediate stability is not 100%, what can be done to prevent the return of bite opening in both the short and long terms?

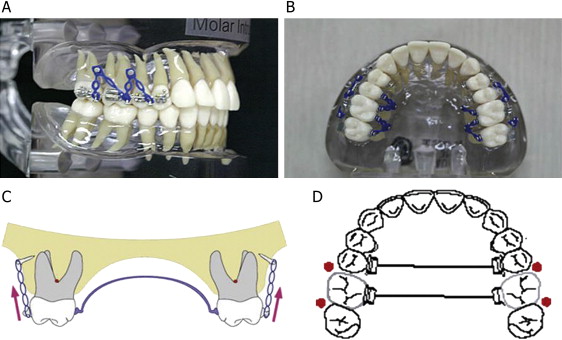

In this clinical study, 9 patients treated with miniscrew implants to intrude the maxillary posterior teeth were followed for at least 3 years posttreatment. The subjects were selected according to the following criteria: (1) diagnosed with incisal open bite (incisor overbite, <–1.0 mm), (2) high SN-MP angle (>40°), and (3) skeletal Class I or Class II discrepancy (anteroposteriorly). Two methods were used for intrusion of the maxillary molars. The first method called for placement of the miniscrew implants on the buccal and palatal sides between the roots of the maxillary second premolar and first molar, and between the roots of the maxillary first and second molars. After 1 to 2 weeks, an intrusive force was directly applied to the molars with elastomeric chains ( Fig 1 , A and B ). The second method called for the placement of miniscrew implants on the buccal side only between the roots of the maxillary second premolar and first molar, and between the roots of the maxillary first and second molars. Rigid transpalatal arches were placed before applying an intrusive force to prevent buccal tipping of the teeth ( Fig 1 , C and D ). FLOAT NOT FOUND

After the authors evaluated all data, they found no significant difference between the 2 methods in the amounts of intrusion achieved. They concluded that the overall pattern of relapse was similar to that of surgical treatment. Downward displacement of the posterior nasal spine, eruption of the maxillary molars, and downward and backward rotation of the mandible resembled the relapse after orthognathic surgery. Such events after surgery are allegedly induced by physiologic adaptations of adjacent muscles and soft tissues to the altered skeletal structures and thus the function. A tooth displaced intrusively is much less stable than one displaced either mesiodistally or rotationally; 1 reason is that there is no effective way to retain an intruded tooth. More than 80% of relapse of the intruded maxillary first molars occurred during the first year of retention. A significant amount of overbite relapse also occurred at the end of the first year but not between the end of the first year and the third year. After completing this study documenting relapse, the authors devised a more effective way of preventing molar extrusion or relapse by fabricating a clear retention device with buttons on the buccal side for wearing elastics directly to the miniscrew implants for additional anchorage. Although not part of this study, it is expected that this method of retention might prove effective in the future.