With the importance of cosmetic appearance in today’s society, the ears are often overlooked until a traumatic event leads to an acquired deformity. Because the long-term psychological effects of the disfigurement can be devastating, the ability to correct these injuries can have a life-changing effect on the patient. The surgeon not only must be prepared to treat the initial injury but must also be familiar with the continued pathogenesis of injury and its treatment to provide the best overall care for the patient.

Etiopathogenesis/Causative Factors

Because of the prominent and exposed position of the ears in the maxillofacial region they routinely experience trauma. Increasing the likelihood of trauma to the ears is the natural inclination to turn one’s face away from impending trauma, thus escalating the severity and incidence of damage. Violent altercations, motor vehicle accidents, thermal insults, and other sources of trauma can cause a vast array of injuries. Steffin and colleagues reviewed 56 publications including 74 cases of auricular avulsion and found that more than a third were caused by bites from humans and animals.

After the initial reconstruction, postoperative care can be challenging because of potential complications unique to this area of the maxillofacial region. These potential challenges in surgical repair of the auricle extend beyond trauma and include sequelae from elective cosmetic surgery, pathologic resection, body piercing, and infection.

Pathologic Anatomy

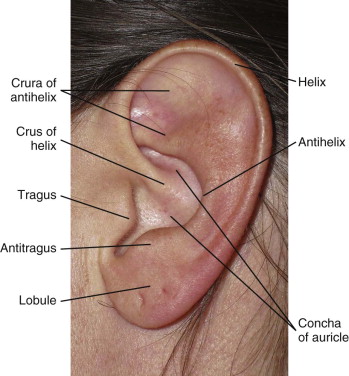

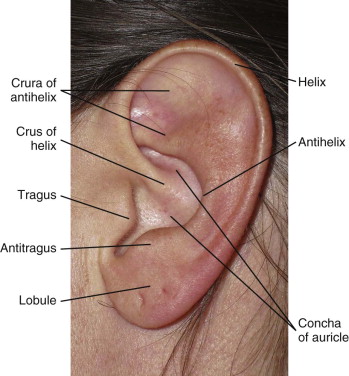

The external ear consists of the auricle, external acoustic meatus, and tympanic membrane, which function together to receive and transmit sound waves to the middle ear. The auricle is traditionally broken down into subunits ( Fig. 67-1 ). The avascular cartilage providing the semi-rigid configuration of the auricle is a primary concern in the treatment and postoperative management of an ear injury.

Symmetry of the ears in both their location and proportion is critical for pleasant esthetics. Normal adult ear height is between 5.5 and 6.6 cm, and its width is approximately 55% of the height. Lateral projection of the ear from the head should be between 1.5 and 2 cm.

As with most soft tissue of the maxillofacial region, the ears have a plentiful and unique blood supply. Ascending anteriorly, the superficial temporal artery can provide a combination of one to three branches to the ear. The upper branch supplies the superior auricle, the middle branch ends at the tragus, and finally, a lower branch supplies the lobule. The posterior auricular artery courses between the meatal cartilage and mastoid and provides branches to the upper and middle auricle.

The skin of the ear and perichondrium is supplied by a vast array of arterioles and venules, whereas the cartilage is avascular and relies on the perichondrium for diffusion of oxygen and removal of metabolic waste. Shearing forces from blunt trauma may cause tearing of the perichondrium with bleeding into the space between the avascular cartilage and perichondrium. This bleeding or extravasation of serous fluid can become trapped beneath the perichondrium and prevent the metabolically necessary transport, and damage to the cartilage is likely to occur. Damage can occur in the form of necrosis of the cartilage and make further reconstruction difficult.

Another possible outcome of a collection beneath the perichondrium is a “cauliflower ear,” an unsightly thickening of the ear formed by fibrosis and the creation of new, haphazard cartilage. Incision plus drainage of the collection is only one part of the treatment; occlusive dressings are required to prevent recurrence. Hematoma and seroma also increase the risk for development of an infection, which can also cause permanent damage to the structure of the auricular cartilage and leave the patient with a disfigured ear after resolution of the infection.

The risk for keloid formation on the ear is higher than in other areas of the body. This can present further complications with any procedure involving the ear, including repair of traumatic injury. Prevention and treatment of keloids are discussed in more detail later in the text.

Pathologic Anatomy

The external ear consists of the auricle, external acoustic meatus, and tympanic membrane, which function together to receive and transmit sound waves to the middle ear. The auricle is traditionally broken down into subunits ( Fig. 67-1 ). The avascular cartilage providing the semi-rigid configuration of the auricle is a primary concern in the treatment and postoperative management of an ear injury.

Symmetry of the ears in both their location and proportion is critical for pleasant esthetics. Normal adult ear height is between 5.5 and 6.6 cm, and its width is approximately 55% of the height. Lateral projection of the ear from the head should be between 1.5 and 2 cm.

As with most soft tissue of the maxillofacial region, the ears have a plentiful and unique blood supply. Ascending anteriorly, the superficial temporal artery can provide a combination of one to three branches to the ear. The upper branch supplies the superior auricle, the middle branch ends at the tragus, and finally, a lower branch supplies the lobule. The posterior auricular artery courses between the meatal cartilage and mastoid and provides branches to the upper and middle auricle.

The skin of the ear and perichondrium is supplied by a vast array of arterioles and venules, whereas the cartilage is avascular and relies on the perichondrium for diffusion of oxygen and removal of metabolic waste. Shearing forces from blunt trauma may cause tearing of the perichondrium with bleeding into the space between the avascular cartilage and perichondrium. This bleeding or extravasation of serous fluid can become trapped beneath the perichondrium and prevent the metabolically necessary transport, and damage to the cartilage is likely to occur. Damage can occur in the form of necrosis of the cartilage and make further reconstruction difficult.

Another possible outcome of a collection beneath the perichondrium is a “cauliflower ear,” an unsightly thickening of the ear formed by fibrosis and the creation of new, haphazard cartilage. Incision plus drainage of the collection is only one part of the treatment; occlusive dressings are required to prevent recurrence. Hematoma and seroma also increase the risk for development of an infection, which can also cause permanent damage to the structure of the auricular cartilage and leave the patient with a disfigured ear after resolution of the infection.

The risk for keloid formation on the ear is higher than in other areas of the body. This can present further complications with any procedure involving the ear, including repair of traumatic injury. Prevention and treatment of keloids are discussed in more detail later in the text.

Diagnostic Studies

Most evaluations of an acute ear injury will occur in the emergency department. As with any trauma, the principles of advanced trauma life support should be followed when indicated. Computed tomography of the head may be necessary if the consultant suspects an intracranial injury. Evaluation of an injury to the ear begins with assessment of the auricle and other external ear landmarks. Otoscopic examination of the tympanic membrane and the ear canal should be performed before treatment. Hearing assessment should also be performed before definitive care.

Reconstructive Goals

Reconstruction of the ear presents the surgeon with unique challenges not encountered elsewhere in the maxillofacial region. The anatomy of the ear, with its relatively thin layer of skin overlying the perichondrium and avascular cartilage, tends to increase the risk for poor surgical outcomes. An understanding of the pathogenesis of complications in ear reconstruction is necessary to prevent a poor surgical result. As mentioned previously, bilateral symmetry and correct proportion of the anatomic features of the ear are equally important considerations in ear reconstruction to achieve the best esthetic results.

Trauma

There are various and challenging techniques to repair trauma to the ear. It is not the author’s intent to cover every existing method for reconstruction of the ear but just to inform readers of an assortment of techniques that they may include in their surgical armamentarium. The initial step is to categorize the wound. Once categorized, the treatment with the best surgical outcome may be used. When considering trauma to the auricle, the wounds are classified as laceration, extended laceration, partial avulsion, and total avulsion.

Lacerations

Ear lacerations are usually easily treated in the emergency department under local anesthesia. The general principles of wound repair are the same for the ear as they are elsewhere on the face. First is copious irrigation and débridement. The ear is then repaired with 6-0 non-absorbable monofilament sutures through the skin in correct anatomic position. When repairing lacerations there is usually no need for sutures in the cartilage of the auricle.

Extended Lacerations

An extended laceration is defined as any large laceration that has greatly disrupted the anatomy of the external ear and yet enough tissue remains attached to provide the displaced segment with a blood supply. Again, the general principles of wound repair are followed. It is essential for the bridge of tissue to remain attached. Because the soft tissue of the ear is so vascular, pedicles of skin with a small base tend to survive better here than elsewhere in the body. The segments are approximated in correct anatomic position and sutured with 6-0 non-absorbable monofilament suture through the skin. Sutures are placed within the auricular cartilage only when deemed necessary and are kept to a minimum. Too many sutures through the avascular cartilage may lead to devitalization of that particular region of the cartilage. Sutures through the cartilage have a tendency to erode through the thin overlying tissue and cause unsightly markings, as well as being a nidus for infection. If sutures do erode through the skin, they must be removed with minimal damage to the overlying skin.

Although the arterial supply to the ear is generous, venous outflow is questionable in a recent injury, especially avulsions. Large extended lacerations with a minimal bridge of tissue may be accompanied by the development of venous congestion. Leech therapy or any other anticoagulation techniques may be needed in the postoperative period.

Partial Avulsion

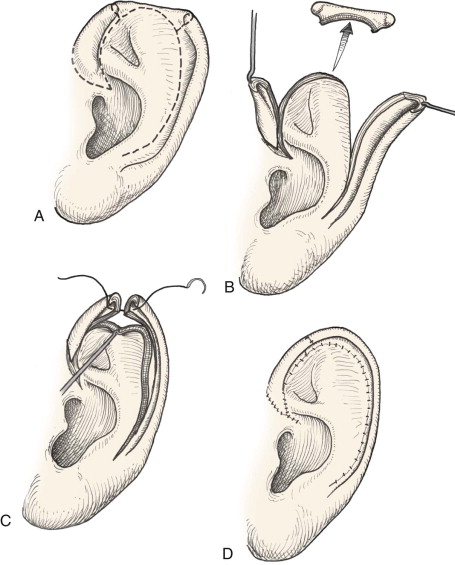

Acute traumatic avulsion of auricular tissue can range from very small defects to full avulsions. The type of reconstruction depends on the size of the defect and the region of the helix affected. Acquired defects of the superior auricle no larger than 2 cm can be repaired primarily by advancing the helix in both directions. As described by Antia and Buch, the entire helix is freed from the scapha, and incisions are made in the helical sulcus and cartilage to advance the two flaps and retain the anatomic contour of the superior helix ( Fig. 67-2 ).

Middle auricle defects 2 cm or smaller can again be closed primarily with the help of Burrow triangles to allow approximation of tissue without tension. Lower third auricular defects are difficult to repair because of their lack of cartilaginous support. Various techniques have been described to repair a traumatically missing earlobe. Local skin flaps as reported by Converse and Brent and even a combination cartilage and skin flap have been described.

Larger defects will need increasingly complex reconstructive techniques to achieve esthetic acceptance. If the avulsion is large enough, microvascular anastomosis may be achieved, although it is very rare for partial avulsions to have recipient vessels sufficient for the anastomosis. Depending on the amount of cartilage lost, a variety of techniques involving local skin flaps, contralateral conchal cartilage, and rib cartilage can be used ( Fig. 67-3 ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses