Introduction

Our objective was to assess the accuracy, validity, and reliability of measurements obtained from virtual dental study models compared with those obtained from plaster models.

Methods

PubMed, PubMed Central, National Library of Medicine Medline, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Clinical trials, Web of Knowledge, Scopus, Google Scholar, and LILACs were searched from January 2000 to November 2014. A grading system described by the Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care and the Cochrane tool for risk of bias assessment were used to rate the methodologic quality of the articles.

Results

Thirty-five relevant articles were selected. The methodologic quality was high. No significant differences were observed for most of the studies in all the measured parameters, with the exception of the American Board of Orthodontics Objective Grading System.

Conclusions

Digital models are as reliable as traditional plaster models, with high accuracy, reliability, and reproducibility. Landmark identification, rather than the measuring device or the software, appears to be the greatest limitation. Furthermore, with their advantages in terms of cost, time, and space required, digital models could be considered the new gold standard in current practice.

Highlights

- •

Digital models are as reliable as plaster models for orthodontic purposes.

- •

Lack of accuracy of measurements on digital models is not clinically significant.

- •

Digital models should be considered the new gold standard in orthodontics.

During the past 10 years, models and facial scanning, as well as cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) technologic advancements, have permitted the complete virtualization of the orthodontic patient, with more accurate 3-dimensional (3D) reconstructions of teeth, bones, and soft tissues. Plaster models are the gold standard in dental diagnosis and treatment procedures. However, they require rigorous archiving and massive physical storage space. Moreover, plaster models are not practical in the long term because of breakage and degradation issues.

Digital study models were introduced commercially in late 1990s. Different technologies can be used to generate digital study casts. This is why standardization issues are still important. Furthermore, different technologies might account for the differences between conventional plaster and digital models.

The diagnostic accuracy and measurement sensitivity of digital models compared with plaster models are the most investigated issues. In 2011, Fleming et al performed a systematic review of the literature focused on the comparisons between measurements on digital models and measurements with digital calipers on plaster models. The authors stated that “digital models offer a high degree of validity when compared to direct measurement on plaster models.” However, the overall quality of the selected studies was variable, with generally inadequate descriptions of the sample populations and rare reports of confidence intervals and standard errors between different techniques. Another review by Luu et al published in 2012 analyzed intrarater reliabilities in terms of mean differences, intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs), and Pearson correlation coefficients (PCCs) of measurements of digital models compared with gypsum casts. The authors agreed with Fleming et al, stating that validity and reliability for all parameters showed clinically nonsignificant differences. Furthermore, as stated by the authors, only quantitative linear measurements were analyzed, excluding from the review all articles treating qualitative ordinal measures such as orthodontic indexes or scales (ie, Peer Assessment Rating [PAR], American Board of Orthodontics [ABO] Objective Grading System, and Index of Complexity, Outcome, and Need [ICON]).

Considering the velocity of the technologic advancements in scanning and digital models in recent years, the aims of our study were to conduct a systematic review to update the data in these 2 reviews and to find answers to a clinical research question related to the use of digital study models in orthodontic practice: What are the accuracy, validity, and reliability of measurements obtained from virtual dental study models compared with those obtained from plaster models?

To try to answer this question, articles about orthodontics indexes or scales were included in our review.

Material and methods

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for this systematic review ( Table I ) were based on the type of study and were dependent on the clinical research questions. Case reports, reviews, abstracts, author debates, summary articles, and animal studies were excluded from the review process. However, the reference lists of those articles were perused and followed up.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Prospective and retrospective original studies analyzing treated and untreated orthodontic patients with or without malocclusion | Studies of patients with genetic syndromes and severe facial malformations |

| Studies analyzing measurements made on digital and plaster models | Studies with fewer than 10 patients |

| Studies with adequate statistical analysis | Case reports |

| Reviews | |

| Abstracts | |

| Author debates | |

| Summary articles |

Information sources, search strategy, and study selection

On November 1, 2014, a systematic search in the medical literature produced between January 2000 and November 2014 was performed to identify all peer-reviewed articles potentially relevant to our questions to be included in the review. The research was performed in the following databases: PubMed, PubMed Central, National Library of Medicine Medline, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Clinical Trials, Web of Knowledge, Scopus, Google Scholar, and LILACS.

The same search strategy was used and adapted to the syntax of the different databases. An example of the string used on PubMed is provided in Table II .

| Database | Search strategy |

|---|---|

| PubMed, PubMed Central, Scopus, Web of Knowledge, Embase, National Library of Medicine Medline | ((3d OR digital OR intraoral OR electronic or computer ∗ OR software) AND (impression ∗ OR model ∗ OR cast ∗ OR scanner ∗ OR cad/cam OR cad cam OR cad-cam)) AND (orthodontics OR orthod ∗ ) AND (accuracy OR precision OR effic ∗ OR limitat ∗ ) |

∗ The asterisk is a PubMed operator for optimizing the search query.

A hand search was performed for additional articles in the medical library of the University of Turin in Italy, the authors’ personal libraries, and the references of the selected articles. Titles and abstracts were screened to select articles for full-text retrieval.

If there was disagreement between the investigators, inclusion of the study was confirmed by mutual agreement.

The studies were selected for inclusion independently by 2 authors (G.R. and S.P.). All decisions on the definitive inclusion of a potentially relevant article were made by consensus.

From the selected articles, the investigators independently extracted data answering the clinical research questions.

Data items and collection

To extract data from the selected articles, we used a table to report for every article sample size, measurements evaluated, mean differences, P values, standard errors, and confidence intervals ( Appendix 1 ). A separate table was used to evaluate the results of articles analyzing the ABO Objective Grading System score ( Appendix 2 ).

Reliability indexes were included in a separate table for every article: sample size, ICC values, PCCs, and other reliability methods, if calculated ( Appendix 3 ).

All studies were assessed separately; in cases of divergent assessments with regard to the assignment of strengths and weaknesses, consensus was reached by discussion.

Risk of bias and quality assessment in the studies

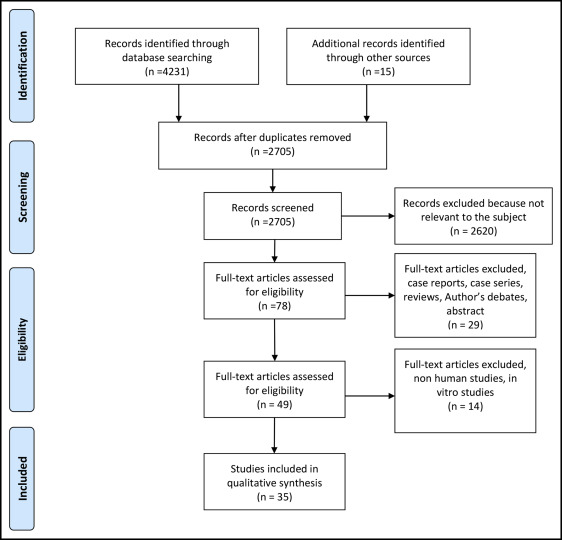

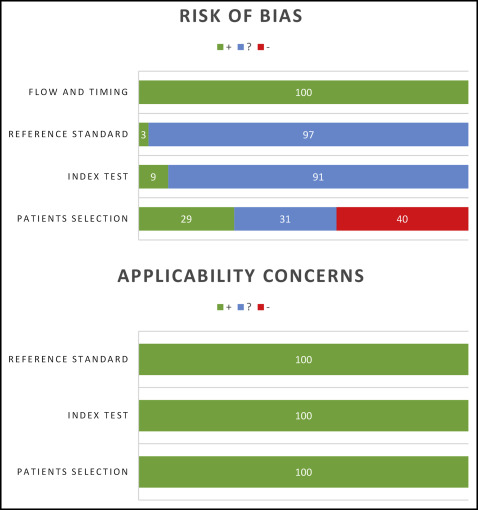

According to the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination at the University of York in the United Kingdom and the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statements, evaluation of methodologic quality gives an indication of the strength of the evidence in the study because flaws in the design or the conduct of a study can result in biases. The Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2) tool was used to rate the methodologic quality of the articles and to assess the level of evidence for the conclusions of this review ( Tables III and IV , Fig 1 ).

| Risk of bias | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient selection | Index test | Reference standard | Flow and timing | |

| Nouri et al, 2014 | − | ? | ? | + |

| Hajeer, 2014 | + | ? | ? | + |

| De Waard et al, 2014 | − | ? | ? | + |

| Burns et al, 2014 | ? | ? | ? | + |

| Im et al, 2014 | − | ? | ? | + |

| Radeke et al, 2014 | − | + | + | + |

| Akyalcin et al, 2013 | ? | ? | ? | + |

| Naidu and Freer, 2013 | + | ? | ? | + |

| Nalcaci et al, 2013 | − | ? | ? | + |

| Wiranto et al, 2013 | − | ? | ? | + |

| Abizadeh et al, 2012 | − | ? | ? | + |

| Lightheart et al, 2012 | ? | ? | ? | + |

| Sousa et al, 2012 | ? | ? | ? | + |

| Tarazona et al, 2012 | − | ? | ? | + |

| El-Zanaty et al, 2010 | ? | + | ? | + |

| Horton et al, 2010 | ? | + | ? | + |

| Kau et al, 2010 | ? | ? | ? | + |

| Sjogren et al, 2010 | + | ? | ? | + |

| Leifert et al, 2009 | + | ? | ? | + |

| Veenema et al, 2009 | + | ? | ? | + |

| Watanabe-Kanno et al, 2009 | + | ? | ? | + |

| Goonewardene et al, 2008 | − | ? | ? | + |

| Hildebrand et al, 2008 | + | ? | ? | + |

| Keating et al, 2008 | + | ? | ? | + |

| Redlich et al, 2008 | ? | ? | ? | + |

| Cha et al, 2007 | − | ? | ? | + |

| Mullen et al, 2007 | ? | ? | ? | + |

| Stevens et al, 2006 | + | ? | ? | + |

| Mayers et al, 2005 | + | ? | ? | + |

| Costalos et al, 2004 | − | ? | ? | + |

| Okunami et al, 2004 | ? | ? | ? | + |

| Quimby et al, 2004 | − | ? | ? | + |

| Bell et al, 2003 | ? | ? | ? | + |

| Santoro et al, 2003 | − | ? | ? | + |

| Tomassetti et al, 2001 | − | ? | ? | + |

| Applicability concerns | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient selection | Index test | Reference standard | |

| Nouri et al, 2014 | + | + | + |

| Hajeer, 2014 | + | + | + |

| De Waard et al, 2014 | + | + | + |

| Burns et al, 2014 | + | + | + |

| Im et al, 2014 | + | + | + |

| Radeke et al, 2014 | + | + | + |

| Akyalcin et al, 2013 | + | + | + |

| Naidu and Freer, 2013 | + | + | + |

| Nalcaci et al, 2013 | + | + | + |

| Wiranto et al, 2013 | + | + | + |

| Abizadeh et al, 2012 | + | + | + |

| Lightheart et al, 2012 | + | + | + |

| Sousa et al, 2012 | + | + | + |

| Tarazona et al, 2012 | + | + | + |

| El-Zanaty et al, 2010 | + | + | + |

| Horton et al, 2010 | + | + | + |

| Kau et al, 2010 | + | + | + |

| Sjogren et al, 2010 | + | + | + |

| Leifert et al, 2009 | + | + | + |

| Veenema et al, 2009 | + | + | + |

| Watanabe-Kanno et al, 2009 | + | + | + |

| Goonewardene et al, 2008 | + | + | + |

| Hildebrand et al, 2008 | + | + | + |

| Keating et al, 2008 | + | + | + |

| Redlich et al, 2008 | + | + | + |

| Cha et al, 2007 | + | + | + |

| Mullen et al, 2007 | + | + | + |

| Stevens et al, 2006 | + | + | + |

| Mayers et al, 2005 | + | + | + |

| Costalos et al, 2004 | + | + | + |

| Okunami et al, 2004 | + | + | + |

| Quimby et al, 2004 | + | + | + |

| Bell et al, 2003 | + | + | + |

| Santoro et al, 2003 | + | + | + |

| Tomassetti et al, 2001 | + | + | + |

Summary measures and approach to synthesis

Clinical heterogeneity of the included studies was evaluated by assessing the treatment protocols: participants and settings, index tests, and measurement techniques. For accuracy of measurements, mean differences, with standard errors and 95% confidence intervals, were reported when available. For reliability, ICC values and PCCs were extracted from the studies.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

A search with the terms shown in Table II gave the following results: PubMed yielded 475 publications; PubMed Central, 2880 publications; Cochrane Central Register, 11 publication; Web of Knowledge, 392 publications; Scopus, 458 publications; and LILACS, 15 publications. In addition, 15 articles were identified through hand searching. The selection process is illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram ( Fig 2 ).