Diagnosis

examination

GENERAL EXAMINATION

VITAL SIGNS

Vital signs include conscious state, temperature, pulse, blood pressure and respiration:

The conscious state: any decrease in this must be taken seriously, causes ranging from drug use to head injury.

The conscious state: any decrease in this must be taken seriously, causes ranging from drug use to head injury.

The temperature: the temperature is traditionally taken with a thermometer, but temperature-sensitive strips and sensors are available. Leave the thermometer in place for at least 3 min. The normal body temperatures are: oral 36.6°C; rectal or ear (tympanic membrane) 37.4°C; and axillary 36.5°C. Body temperature is usually slightly higher in the evenings. In most adults, an oral temperature above 37.8°C or a rectal or ear temperature above 38.3°C is considered a fever (pyrexia). A child has a fever when ear temperature is 38°C or higher.

The temperature: the temperature is traditionally taken with a thermometer, but temperature-sensitive strips and sensors are available. Leave the thermometer in place for at least 3 min. The normal body temperatures are: oral 36.6°C; rectal or ear (tympanic membrane) 37.4°C; and axillary 36.5°C. Body temperature is usually slightly higher in the evenings. In most adults, an oral temperature above 37.8°C or a rectal or ear temperature above 38.3°C is considered a fever (pyrexia). A child has a fever when ear temperature is 38°C or higher.

The pulse: this can be measured manually or automatically (Fig. 2.1). The pulse can be recorded from any artery, but in particular from the following sites:

The pulse: this can be measured manually or automatically (Fig. 2.1). The pulse can be recorded from any artery, but in particular from the following sites:

Pulse rates at rest in health are approximately as follows:

Pulse rate is increased in:

The rhythm should be regular; if not, ask a physician for advice. The character and volume vary in certain disease states and require a physician’s advice.

The blood pressure: this can be measured with a sphygmomanometer (Fig. 2.2), or one of a variety of machines. With a sphygmomanometer the procedure is as follows: seat the patient; place the sphygmomanometer cuff on the right upper arm, with about 3 cm of skin visible at the antecubital fossa; palpate the radial pulse; inflate the cuff to about 200–250 mmHg or until the radial pulse is no longer palpable; deflate the cuff slowly while listening with the stethoscope over the brachial artery on the skin of the inside arm below the cuff; record the systolic pressure as the pressure when the first tapping sounds appear; deflate the cuff further until the tapping sounds become muffled (diastolic pressure); repeat; record the blood pressure as systolic/diastolic pressures (normal values about 120/80 mmHg, but these increase with age).

The blood pressure: this can be measured with a sphygmomanometer (Fig. 2.2), or one of a variety of machines. With a sphygmomanometer the procedure is as follows: seat the patient; place the sphygmomanometer cuff on the right upper arm, with about 3 cm of skin visible at the antecubital fossa; palpate the radial pulse; inflate the cuff to about 200–250 mmHg or until the radial pulse is no longer palpable; deflate the cuff slowly while listening with the stethoscope over the brachial artery on the skin of the inside arm below the cuff; record the systolic pressure as the pressure when the first tapping sounds appear; deflate the cuff further until the tapping sounds become muffled (diastolic pressure); repeat; record the blood pressure as systolic/diastolic pressures (normal values about 120/80 mmHg, but these increase with age).

OTHER SIGNS

Weight: weight loss is seen mainly in starvation, malnutrition, eating disorders, cancer (termed cachexia), HIV disease (termed ‘slim disease’), malabsorption and tuberculosis and may be extreme as in emaciation. Obesity is usually due to excessive food intake and insufficient exercise.

Weight: weight loss is seen mainly in starvation, malnutrition, eating disorders, cancer (termed cachexia), HIV disease (termed ‘slim disease’), malabsorption and tuberculosis and may be extreme as in emaciation. Obesity is usually due to excessive food intake and insufficient exercise.

Hands: conditions such as arthritis (mainly rheumatoid or osteoarthritis) (Figs 2.3 and 2.4) and Raynaud phenomenon (Ch. 56; Fig. 2.3), which is seen in many connective tissue diseases, may be obvious. Disability, such as in cerebral palsy, may be obvious (Fig. 2.5).

Hands: conditions such as arthritis (mainly rheumatoid or osteoarthritis) (Figs 2.3 and 2.4) and Raynaud phenomenon (Ch. 56; Fig. 2.3), which is seen in many connective tissue diseases, may be obvious. Disability, such as in cerebral palsy, may be obvious (Fig. 2.5).

Skin: lesions, such as rashes – particularly blisters (seen mainly in skin diseases, infections and drug reactions), pigmentation (seen in various ethnic groups, Addison disease and as a result of some drug therapy).

Skin: lesions, such as rashes – particularly blisters (seen mainly in skin diseases, infections and drug reactions), pigmentation (seen in various ethnic groups, Addison disease and as a result of some drug therapy).

Skin appendages: nail changes, such as koilonychia (spoon-shaped nails) – seen in iron deficiency anaemia, hair changes, such as alopecia, and finger clubbing (Fig. 2.6), seen mainly in cardiac or respiratory disorders. Nail beds may reveal the anxious nature of the nail-biting person (Fig. 2.7).

Skin appendages: nail changes, such as koilonychia (spoon-shaped nails) – seen in iron deficiency anaemia, hair changes, such as alopecia, and finger clubbing (Fig. 2.6), seen mainly in cardiac or respiratory disorders. Nail beds may reveal the anxious nature of the nail-biting person (Fig. 2.7).

Extraoral head and neck examination

The face should be examined for lesions (Table 2.1) and features such as:

Table 2.1

The commoner descriptive terms applied to lesions

| Term | Meaning |

| Atrophy | Loss of tissue with increased translucency, unless sclerosis is associated |

| Bullae | Visible accumulations of fluid within or beneath the epithelium, >0.5 cm in diameter (i.e. a blister) |

| Cyst | Closed cavity or sac (normal or abnormal) with an epithelial, endothelial or membranous lining and containing fluid or semisolid material |

| Ecchymosis | Macular area of haemorrhage >2 cm in diameter (bruise) |

| Erosion | Loss of epithelium which usually heals without scarring; it commonly follows a blister |

| Erythema | Redness of the mucosa produced by atrophy, inflammation, vascular congestion or increased perfusion |

| Exfoliation | The splitting off of the epithelial keratin in scales or sheets |

| Fibrosis | The formation of excessive fibrous tissue |

| Fissure | Any linear gap or slit in the skin or mucosa |

| Gangrene | Death of tissue, usually due to loss of blood supply |

| Haematoma | A localized tumour-like collection of blood |

| Keloid | A tough heaped-up scar that rises above the rest of the skin, is irregularly shaped and tends to enlarge progressively |

| Macule | A circumscribed alteration in colour or texture of the mucosa |

| Nodule | A solid mass in the mucosa or skin which can be observed as an elevation or can be palpated; it is >0.5 cm in diameter |

| Papule | A circumscribed palpable elevation <0.5 cm in diameter |

| Petechia (pl. petechiae) | A punctate haemorrhagic spot approximately 1–2 mm in diameter |

| Plaque | An elevated area of mucosa >0.5 cm in diameter |

| Pustule | A visible accumulation of free pus |

| Scar | Replacement by fibrous tissue of another tissue that has been destroyed by injury or disease An atrophic scar is thin and wrinkled A hypertrophic scar is elevated with excessive growth of fibrous tissue A cribriform scar is perforated with multiple small pits |

| Sclerosis | Diffuse or circumscribed induration of the submucosal and/or subcutaneous tissues |

| Tumour | Literally a swelling The term is used to imply enlargement of the tissues by normal or pathological material or cells that form a mass The term should be used with care, as many patients believe it implies a malignancy with a poor prognosis |

| Ulcer | A loss of epithelium, often with loss of underlying tissues, produced by sloughing of necrotic tissue |

| Vegetation | A growth of pathological tissue consisting of multiple closely set papillary masses |

| Vesicle | Small (<0.5 cm in diameter) visible accumulation of fluid within or beneath the epithelium (i.e. small blister) |

| Wheal | A transient area of mucosal or skin oedema, white, compressible and usually evanescent (AKA urticaria) |

swellings, seen in inflammatory and neoplastic disorders in particular

swellings, seen in inflammatory and neoplastic disorders in particular

pallor, seen mainly in the conjunctivae or skin creases in anaemia

pallor, seen mainly in the conjunctivae or skin creases in anaemia

rash, such as the malar rash in systemic lupus erythematosus. Malar erythema may indicate mitral valve stenosis.

rash, such as the malar rash in systemic lupus erythematosus. Malar erythema may indicate mitral valve stenosis.

erythema, seen mainly on the face in an embarrassed or angry patient, or fever (sweating or warm hands), and then usually indicative of infection.

erythema, seen mainly on the face in an embarrassed or angry patient, or fever (sweating or warm hands), and then usually indicative of infection.

Eyes should be assessed for visual acuity and examined for features such as:

corneal arcus which may be seen in hypercholesterolaemia

corneal arcus which may be seen in hypercholesterolaemia

exophthalmos (prominent eyes), seen mainly in Graves thyrotoxicosis

exophthalmos (prominent eyes), seen mainly in Graves thyrotoxicosis

jaundice, seen mainly in the sclerae in liver disease

jaundice, seen mainly in the sclerae in liver disease

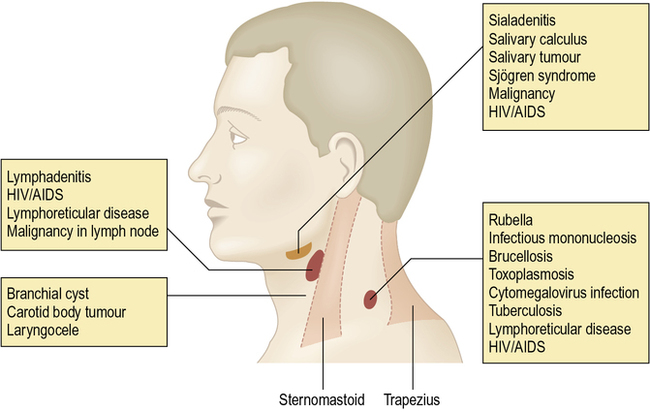

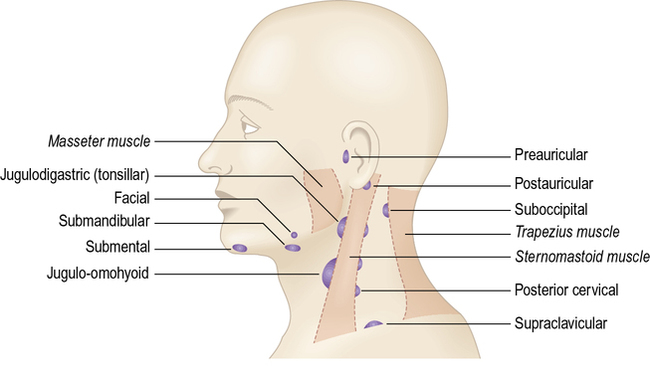

Inspection of the neck, looking particularly for swellings or sinuses, should be followed by careful palpation of all cervical lymph nodes and salivary and thyroid glands, searching for swelling or tenderness. The neck is best examined by observing the patient from the front, noting any obvious asymmetry or swelling, then standing behind the seated patient to palpate the lymph nodes (Fig. 2.8). Systematically, each region needs to be examined lightly with the pulps of the fingers, trying to roll the lymph nodes against harder underlying structures:

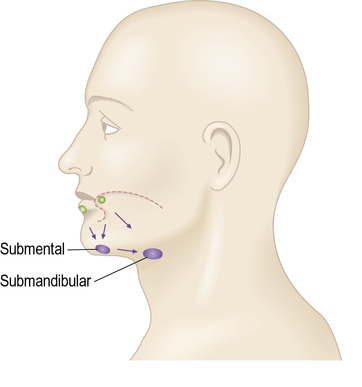

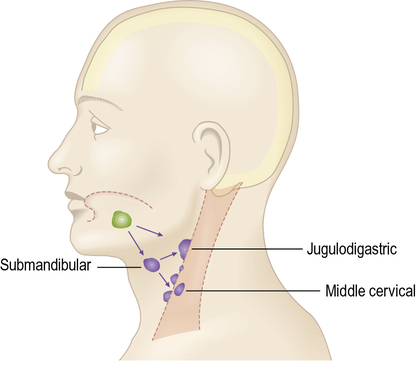

Lymph from the superficial tissue of the head and neck generally drains first to groups of superficially placed lymph nodes, then to the deep cervical lymph nodes (Figs 2.9–2.12 and Table 2.2).

Lymph from the superficial tissue of the head and neck generally drains first to groups of superficially placed lymph nodes, then to the deep cervical lymph nodes (Figs 2.9–2.12 and Table 2.2).

Table 2.2

The cervical lymph nodes and their main drainage areas

| Area | Draining lymph nodes |

| Scalp, temporal region | Superficial parotid (pre-auricular) |

| Scalp, posterior region | Occipital |

| Scalp, parietal region | Mastoid |

| Ear, external | Superficial cervical over upper part of sternomastoid muscle |

| Ear, middle | Parotid |

| Over angle of mandible | Superficial cervical over upper part of sternomastoid muscle |

| Medial part of frontal region, medial eyelids, skin of nose | Submandibular |

| Lateral part of frontal region, lateral part of eyelids | Parotid |

| Cheek | Submandibular |

| Upper lip | Submandibular |

| Lower lip | Submental |

| Lower lip, lateral part | Submandibular |

| Mandibular gingivae | Submandibular |

| Maxillary teeth | Deep cervical |

| Maxillary gingivae | Deep cervical |

| Tongue tip | Submental |

| Tongue, anterior two-thirds | Submandibular, some midline cross-over of lymphatic drainage |

| Tongue, posterior third | Deep cervical |

| Tongue ventrum | Deep cervical |

| Floor of mouth | Submandibular |

| Palate, hard | Deep cervical |

| Palate, soft | Retropharyngeal and deep cervical |

| Tonsil | Jugulodigastric |

Parotid, mastoid and occipital lymph nodes can be palpated simultaneously using both hands.

Parotid, mastoid and occipital lymph nodes can be palpated simultaneously using both hands.

Superficial cervical lymph nodes are examined with lighter fingers as they can only be compressed against the softer sternomastoid muscle.

Superficial cervical lymph nodes are examined with lighter fingers as they can only be compressed against the softer sternomastoid muscle.

Submental lymph nodes are examined by tipping the patient’s head forward and rolling the lymph nodes against the inner aspect of the mandible.

Submental lymph nodes are examined by tipping the patient’s head forward and rolling the lymph nodes against the inner aspect of the mandible.

Submandibular lymph nodes are examined in the same way, with the patient’s head tipped to the side which is being examined. Differentiation needs to be made between the submandibular salivary gland and submandibular lymph glands. Bimanual examination using one hand beneath the mandible to palpate extraorally and with the other index finger in the floor of the mouth may help.

Submandibular lymph nodes are examined in the same way, with the patient’s head tipped to the side which is being examined. Differentiation needs to be made between the submandibular salivary gland and submandibular lymph glands. Bimanual examination using one hand beneath the mandible to palpate extraorally and with the other index finger in the floor of the mouth may help.

The deep cervical lymph nodes which project anterior or posterior to the sternomastoid muscle can be palpated. The jugulodigastric lymph node in particular should be specifically examined, as this is the most common lymph node involved in tonsillar infections and oral cancer.

The deep cervical lymph nodes which project anterior or posterior to the sternomastoid muscle can be palpated. The jugulodigastric lymph node in particular should be specifically examined, as this is the most common lymph node involved in tonsillar infections and oral cancer.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses