For a girl, aged 12 years 3 months, with a skeletal Class III malocclusion, negative overjet, severe maxillary crowding, and hyperdivergent pattern, orthognathic surgery combined with orthodontic treatment is often the treatment of choice, because it can greatly improve the patient’s facial profile and ensure the long-term stability of the results. However, because of high risks and treatment expenses, patients sometimes refuse to have surgery. We report a nonsurgical combination therapy including facemask and multiloop edgewise archwires and the outcome for a patient with a developing skeletal Class III malocclusion and a long anterior facial height. Treatment included advancement of the maxilla by orthopedic means and counterclockwise rotation of the mandibular occlusal plane by the orthodontic dentoalveolar compensation of distal en-masse movement of the mandibular dentition.

The chief craniofacial features associated with the Class III phenotype are an acute cranial base angle, a short and retrusive maxilla, and a prominent and elongated mandible. However, not all patients with a Class III skeletal relationship exhibit all the characteristic features; rather, they have various combinations of skeletal components. Comparative studies have shown that the prevalence of Class III malocclusions and the underlying skeletal types vary among racial and ethnic groups. In general, reduced anterior cranial base and maxillary deficiency, sometimes accompanied with a large mandible, are more often observed in patients of Mongoloid populations such as Koreans, Japanese, and Chinese.

In Chinese orthodontic practices, skeletal Class III is a common malocclusion. Due to anteroposterior (AP) and vertical maxillary deficiency, the mechanical interference produced by the overclosure of the mandible often influences the growth of the maxilla and the alignment of the maxillary dentition. Many skeletal Class III patients also have severe crowding in the maxillary arch. It has been reported that a skeletal Class III discrepancy worsens with age. Thus, a developing Class III malocclusion with a significant skeletal component and severe crowding in the maxilla is a difficult challenge to orthodontists, especially when a conservative approach is requested.

Additionally, a previous retrospective study indicated that subjects with maxillary retrognathia appeared to have a vertical facial pattern, showing a tendency toward vertical growth as a possible compensation mechanism. For successful treatment of a skeletal Class III malocclusion, the vertical growth pattern is also an important factor to be considered. Reduced lower anterior face height, deep overbite, and passive lip seal associated with a Class III malocclusion have a better prognosis, because treatment-induced backward rotation of the mandible will assist in camouflaging the AP discrepancy. When an increased lower anterior face height is associated with this malocclusion, surgical intervention is usually the treatment of choice, because any orthodontically induced mandibular clockwise rotation will increase the vertical facial dimensions and, consequently, cause lip incompetence. For patients who reject or are not willing to accept surgical therapy and persist in their pursuit of orthodontic treatment, an alternative is to treat them with dentoalveolar compensation. However, which mechanics provide significant dentoalveolar changes without unfavorable side effects? To what extent do nonsurgical treatment approaches improve all aspects of the malocclusion? In an attempt to answer all of these questions, we present the orthodontic treatment of a patient with a long-faced, skeletal Class III malocclusion combined with severe maxillary crowding.

Diagnosis and etiology

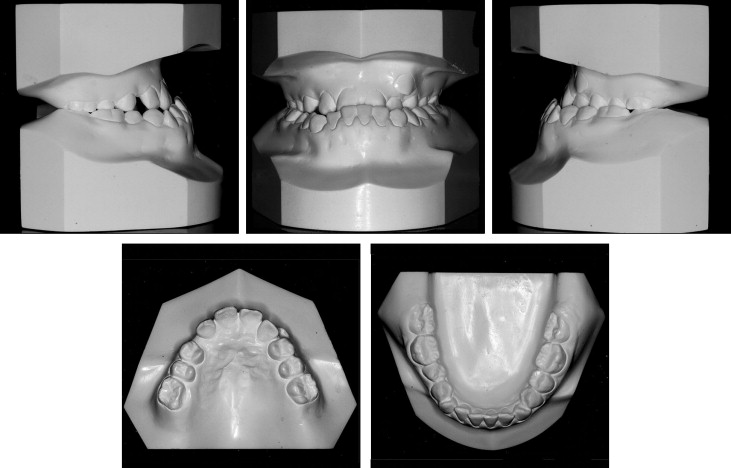

The patient was a girl, aged 12 years 3 months, who had an anterior crossbite and severe crowding with a complete Class III molar relationship on both sides ( Figs 1 and 2 ). She complained of difficulties with mastication and pronunciation. Her facial profile was straight with a long anterior facial height, and no facial asymmetry was observed. Overjet was negative. None of the patient’s direct family members had skeletal Class III features.

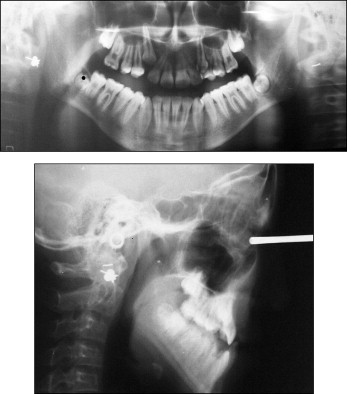

From the dental perspective, there was severe crowding in the maxillary arch and mild crowding in the mandibular arch. The arch-length discrepancies were −14.5 mm in the maxillary arch and −4.5 mm in the mandibular arch. Dental compensation masked the skeletal discrepancies, with a severe lingual inclination of the mandibular incisors (mandibular incisor to mandibular plane, 78°). In addition, the mandibular premolars and molars were markedly inclined mesially. Although the maxillary dental midline was deviated 1.0 mm to the left, the mandibular dental midline was coincident with the facial midline. The panoramic radiograph confirmed the presence of the maxillary right canine, unerupted and impacted ( Fig 3 ). Evaluation of the hand-wrist radiograph showed that the epiphysis of the middle phalanx of the middle finger was the same width as the diaphysis ( Fig 4 ), indicating that the patient was approaching the peak of the growth spurt according to Grave and Brown.

The cephalometric analysis indicated the features of a skeletal crossbite ( Table ). The maxilla was significantly retruded (SNA angle, 76.5°) to the cranial base compared with a moderately protruded mandible (SNB angle, 81°), indicating skeletal Class III (ANB angle, −4.5°). The mandible exhibited backward and downward rotation; vertically, the patient had a high face—ie, a hyperdivergent skeletal pattern (FMA, 38°; SN-GoGN, 41°).

| Measurement | Pretreatment | Posttreatment | Postretention |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNA (°) | 76.5 | 81.5 | 80.5 |

| SNB (°) | 81.0 | 81.5 | 82.0 |

| ANB (°) | 4.5 | 0.0 | 1.5 |

| FMA (°) | 38.0 | 39.5 | 39.5 |

| SN-GoGn (°) | 41.0 | 42.0 | 41.0 |

| U1 to SN plane (°) | 96.0 | 104.0 | 107.5 |

| IMPA (°) | 78.0 | 77.0 | 78.0 |

| Occlusal plane-SN (°) | 27.0 | 20.0 | 18.0 |

| Upper lip to E-line (mm) | 4.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Lower lip to E-line (mm) | 0.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

Treatment objectives

Because the patient had a skeletal Class III malocclusion with a long lower anterior facial height, orthognathic surgery combined with orthodontic treatment was proposed to correct the AP basal relationship by surgically advancing the maxilla and retruding the mandible. These changes were expected to greatly improve her facial profile and ensure the long-term stability of the treatment results. However, the risks and treatment expenses would be high. Her parents strongly preferred a nonsurgical treatment approach. Since she was in the pubertal growth spurt, limited treatment objectives, consisting of improving the skeletal jaw relationship as much as possible by growth modification and correcting the occlusal discrepancies by dentoalveolar compensation, were considered. The specific treatment objectives were to (1) correct the skeletal AP discrepancies with improvement of the soft-tissue profile, (2) correct the anterior crossbite and establish positive overjet and overbite, (3) establish Class I molar and canine relationships by uprighting and distalizing the mesially inclined mandibular dentition, (4) eliminate the maxillary and mandibular arch length discrepancies, and (5) follow up the remaining growth to assess the need for further treatment.

Treatment objectives

Because the patient had a skeletal Class III malocclusion with a long lower anterior facial height, orthognathic surgery combined with orthodontic treatment was proposed to correct the AP basal relationship by surgically advancing the maxilla and retruding the mandible. These changes were expected to greatly improve her facial profile and ensure the long-term stability of the treatment results. However, the risks and treatment expenses would be high. Her parents strongly preferred a nonsurgical treatment approach. Since she was in the pubertal growth spurt, limited treatment objectives, consisting of improving the skeletal jaw relationship as much as possible by growth modification and correcting the occlusal discrepancies by dentoalveolar compensation, were considered. The specific treatment objectives were to (1) correct the skeletal AP discrepancies with improvement of the soft-tissue profile, (2) correct the anterior crossbite and establish positive overjet and overbite, (3) establish Class I molar and canine relationships by uprighting and distalizing the mesially inclined mandibular dentition, (4) eliminate the maxillary and mandibular arch length discrepancies, and (5) follow up the remaining growth to assess the need for further treatment.

Treatment alternatives

The patient had a maxillary deficiency along with mandibular excess and a dolichofacial pattern. Because of the potential risk that any orthodontically induced mandibular clockwise rotation would further increase the lower anterior facial dimensions, combined surgical and orthodontic treatment with maxillary advancement and mandibular setback was proposed. Maximum esthetics and ideal occlusion would be possible with this approach. But the patient’s parents refused surgery. They thought that the patient was still young, and they could not accept the result of an unsuccessful operation. Comparatively, they were more willing to accept a less-than-ideal result. Therefore, nonsurgical orthodontic treatment alternatives were considered.

The patient was aged 12 years 3 months at the start of the treatment, so she still had some growth potential to assist in achieving the treatment goals with orthodontics alone. Dentofacial orthopedics, such as rapid maxillary expansion followed by facemask protraction, would be used in the early stage of treatment to induce forward growth of the maxilla. Rapid palatal expansion would be used to open space for the impacted maxillary canines on both sides, since the straight facial profile might be worsened by the extraction of maxillary teeth (canine or premolar). Several dentoalveolar compensation options for the vertical height control were devised.

One option was mandibular extraction including either premolars or second molars. In the former, premolar extractions could cause further linguoversion of the mandibular incisors and mesial inclination of the molars. The Class III molar relationship would not be corrected. In the latter, extraction of both mandibular second molars could establish a Class I buccal and canine occlusion and distally upright the mandibular dentition. But it would most likely require considerable time to retract the premolars and the anterior segment; moreover, it is necessary to follow up the eruption of the third molars to assess the need for further treatment.

Another option was to use a multiloop edgewise archwire (MEAW) to produce distal en-masse movement of the mandibular dentition. Multiple L-loops and tip-back bends with intermaxillary elastics would efficiently upright and distalize the mandibular posterior teeth and change the inclination of the occlusal planes, making it possible to correct the occlusal sagittal relationship and obtain the correct intercuspation in a significantly shorter time. To maximize the mandibular dentoalveolar compensation, if necessary, the mandibular third molars would be extracted later.

We thoroughly discussed all alternatives and explained that, although the risks and costs of orthodontics alone were less than orthognathic surgery, it demanded more time and high patient compliance. Also, the skeletal discrepancy would not be completely corrected, and the facial harmony would be only slightly improved. Nevertheless, the patient refused the surgical approach and opted for nonextraction orthodontic treatment, accepting maxillary protraction during the first stage of treatment. Meanwhile, she promised to cooperate in wearing the protraction facemask and the intermaxillary elastics as instructed.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses