Skin lesions are extremely common, and early detection of dangerous lesions makes skin cancer one of the most highly curable malignancies. By simply becoming aware of common lesions and their phenotypic presentation, dental professionals are empowered to detect suspicious dermatologic lesions in unaware patients. This article serves as an introduction to skin cancer and benign skin lesions for dental professionals.

- •

By becoming aware of common lesions and their phenotypic presentation, dental professionals are empowered to detect suspicious dermatologic lesions in unaware patients.

- •

Skin lesions are extremely common, and early detection of dangerous lesions makes skin cancer one of the most highly curable malignancies.

- •

Dentists can have an impact on the health of their patients by examining the skin, making the appropriate referral, and following up with the patient to determine if they have seen a dermatologist.

Introduction to the skin

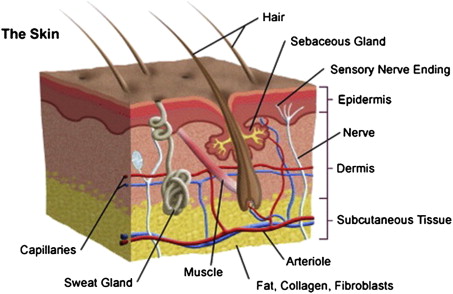

The skin is the largest organ in the body, comprising 18% of body weight and covering a surface area of 1.8 m², and fulfills many vital roles for the human body. It provides protection from the external world, including protection from physical insults, microorganisms, and ultraviolet (UV) irradiation. The skin also fosters a homeostatic internal body environment, ranging from fluid balance to thermoregulation, vitamin D production, and immune regulation. The skin is composed of 3 primary layers: the epidermis, the dermis, and the subcutaneous fat ( Fig. 1 ). The epidermis is a stratified squamous epithelium derived from ectoderm and is composed of 4 principle cell types: keratinocytes, melanocytes, Langerhans cells, and Merkel cells. Skin cancers arise when proliferation involving these cell types becomes dysregulated. The epidermis is separated from the dermis by a basement membrane. The dermis provides structural support and nutrients via connective tissue, rich vascularization, and innervation. The underlying subcutaneous fat is a meshwork of loose connective tissue and fat that provides insulation for the internal body systems and energy storage. The subcutis and the dermis also contain important structures such as sebaceous glands, hair follicles, eccrine glands, and apocrine glands. This basic introduction to skin histology provides a foundation for an understanding of skin pathology ranging from skin cancer and precursor lesions to benign skin proliferations.

Nonmelanoma skin cancer

Skin cancer is broadly categorized into 2 main subtypes: Nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC), and malignant melanoma. NMSC consists of basal cell carcinomas (BSCs) and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). Trends indicate that the incidence of NMSC is rapidly increasing worldwide, affecting more than one million Americans per year. More than 3.5 million skin cancers are diagnosed annually. The estimated average lifetime risk for Caucasians to develop NMSC is upwards of 30%. BSC and SCC are the 2 most common forms of skin cancer, but both are easily treated if detected early. A recent study found that BSC and SCC are increasing in men and women younger than 40 years of age. In the study, BSC increased faster in young women than in young men. In humans, there are more skin cancers than all other cancers, and current estimates are that 1 in 5 Americans will develop skin cancer in their lifetime. Once an individual has developed one NMSC, they are more likely to develop another. One meta-analysis estimates that these patients have a 44% risk of developing an additional skin cancer within 3 years.

Risk Factors

There are several risk factors for developing NMSC ( Box 1 ). NMSC has a predilection for patients with (1) a history of intense UV radiation exposure during childhood (0–19 years of age), (2) Fitzpatrick skin types I–II, (3) blonde or red hair color, (4) light eye color, and (5) chronic photodamaged skin, especially in the head and neck region. The most significant risk factor for the development of NMSC appears to be exposure to UV radiation. However, the timing, pattern, and amount of exposure to UV radiation also seem to be important. The risk of disease is significantly increased by exposure to UV radiation during childhood and adolescence as well as intense intermittent and chronic cumulative sun exposure. Physical factors, including fair complexion, hair and eye color, influence responsiveness to UV radiation and also act as independent risk factors. Other risk factors include a history of diagnostic or therapeutic radiation, arsenic exposure, immunosuppressive therapy for organ transplant recipients, psoralen and UVA radiation, exposure to human papilloma virus, and various genodermatoses such as Gorlin syndrome and xeroderma pigmentosum (see Box 1 ). It has been estimated that 16% of renal transplant patients will develop NMSC, SCC more than BCC, and the risk increases with the length of their immunosuppression. The incidence of BCC in organ transplant recipients is 5 to 10 times greater than its incidence in the general population, whereas the incidence of SCC is 65 to 250 times greater. In the next few sections the authors discuss in detail the 2 types of NMSC, BSC and SCC.

-

Risk Factors for NMSC

-

Ultraviolet radiation

-

Arsenic exposure

-

Ionizing radiation

-

Tanning bed use

-

Red or blond hair

-

Light eye color

-

Fitzpatrick skin types I–II

-

Immunosuppression

-

Genodermatoses

-

Decreasing latitude

Nonmelanoma skin cancer

Skin cancer is broadly categorized into 2 main subtypes: Nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC), and malignant melanoma. NMSC consists of basal cell carcinomas (BSCs) and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). Trends indicate that the incidence of NMSC is rapidly increasing worldwide, affecting more than one million Americans per year. More than 3.5 million skin cancers are diagnosed annually. The estimated average lifetime risk for Caucasians to develop NMSC is upwards of 30%. BSC and SCC are the 2 most common forms of skin cancer, but both are easily treated if detected early. A recent study found that BSC and SCC are increasing in men and women younger than 40 years of age. In the study, BSC increased faster in young women than in young men. In humans, there are more skin cancers than all other cancers, and current estimates are that 1 in 5 Americans will develop skin cancer in their lifetime. Once an individual has developed one NMSC, they are more likely to develop another. One meta-analysis estimates that these patients have a 44% risk of developing an additional skin cancer within 3 years.

Risk Factors

There are several risk factors for developing NMSC ( Box 1 ). NMSC has a predilection for patients with (1) a history of intense UV radiation exposure during childhood (0–19 years of age), (2) Fitzpatrick skin types I–II, (3) blonde or red hair color, (4) light eye color, and (5) chronic photodamaged skin, especially in the head and neck region. The most significant risk factor for the development of NMSC appears to be exposure to UV radiation. However, the timing, pattern, and amount of exposure to UV radiation also seem to be important. The risk of disease is significantly increased by exposure to UV radiation during childhood and adolescence as well as intense intermittent and chronic cumulative sun exposure. Physical factors, including fair complexion, hair and eye color, influence responsiveness to UV radiation and also act as independent risk factors. Other risk factors include a history of diagnostic or therapeutic radiation, arsenic exposure, immunosuppressive therapy for organ transplant recipients, psoralen and UVA radiation, exposure to human papilloma virus, and various genodermatoses such as Gorlin syndrome and xeroderma pigmentosum (see Box 1 ). It has been estimated that 16% of renal transplant patients will develop NMSC, SCC more than BCC, and the risk increases with the length of their immunosuppression. The incidence of BCC in organ transplant recipients is 5 to 10 times greater than its incidence in the general population, whereas the incidence of SCC is 65 to 250 times greater. In the next few sections the authors discuss in detail the 2 types of NMSC, BSC and SCC.

-

Risk Factors for NMSC

-

Ultraviolet radiation

-

Arsenic exposure

-

Ionizing radiation

-

Tanning bed use

-

Red or blond hair

-

Light eye color

-

Fitzpatrick skin types I–II

-

Immunosuppression

-

Genodermatoses

-

Decreasing latitude

Basal cell carcinoma

Cutaneous BCC is the most ubiquitous cancer affecting humans worldwide. Over 1 million cases were detected in the United States in 2010, 95% between ages 40 and 79. BCC accounts for approximately 60% to 75% of all skin cancers. BCC is an indolent, locally invasive, malignant epithelial neoplasm arising from the basilar layer of the epidermis. It slowly progresses, with projections of microtumor spreading in a three-dimensional manner throughout the papillary and reticular dermis, and rarely leads to metastasis. One reason for the apparent limitation to the dermal layer of skin may be tumor dependence on the stromal environment of the dermal fibroblast. BCC is thought to be composed of aberrant follicular germinative cells, also known as trichoblasts, because of its morphologic and immunohistochemical similarities to hair follicle structures.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of BCC is related to genetic mutation. The most common mutated genes in BCC pathogenesis include the PTCH gene on chromosome 9q and point mutations in p53 on chromosome 17p. Both PTCH and p53 are tumor suppressor genes that encode proteins responsible for preventing cell cycle progression. The role that the PTCH gene plays in BCC pathogenesis is highlighted by nevoid BCC syndrome, which results from an inherited autosomal dominant mutation in PTCH gene. People affected by this disorder classically develop hundreds of BCCs, including palmar and plantar pits, odontogenic keratocysts of the jaws, skeletal abnormalities, and calcification of the falx cerebri.

Clinical Presentation

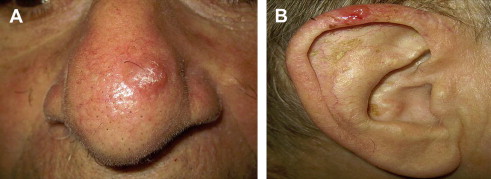

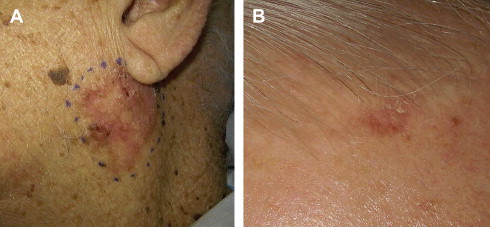

BCC characteristically arises in body areas exposed to the sun and is most common on the head and neck, followed by the trunk, arms, and legs. In addition, BCCs have been reported in unusual sites, including the axillae, breasts, perianal area, genitalia, palms, and soles. BCCs have been classified into 4 main types according to clinical and histopathologic features: superficial, nodular, micronodular, and infiltrative or morpheaform ( Table 1 ). In a retrospective study of more than 10,000 cases of diagnosed BCCs, 79% were nodular, 15% were superficial, and 6% were morpheaform. The nodular and morpheaform types were observed on the head and neck 90% to 95% of the time, whereas 46% of superficial BCCs occurred on the trunk. Nodular BCC is the classic form, which most often presents as a pearly pink to white dome-shaped papule surrounded by a well-demarcated rolled border; prominent telangiectatic vessels may superficially traverse the lesion usually present on the face and ears ( Fig. 2 ). Patients often describe this papule as a nonhealing “pimple” that bleeds occasionally. Superficial BCC presents as a scaly erythematous patch or plaque usually on the trunk or extremities ( Fig. 3 ). The morpheaform type, also known as sclerosing, fibrosing, or infiltrative BCC, typically appears as an indurated, whitish, scarlike plaque with indistinct margins ( Fig. 4 ). This type of BCC is slightly tougher to diagnose because of its ill-defined margins and often present later. The value of classifying the histologic appearance of BCC lies in the relationship between histologic subtype and clinical behavior. Aggressive histologic variants include micronodular, infiltrative, basosquamous, morpheaform, and mixed subtypes. Nodular and superficial subtypes generally have a less aggressive clinical course.

| BCC Varieties | Unique Features |

|---|---|

| Nodular | Most common BCC (60%), raised and translucent papule or nodule with telangiectasias, often on face, may ulcerate, may be pigmented (hard to tell from melanoma) |

| Superficial | Erythematous macule or thin plaque, trunk and extremities>head and neck |

| Morpheaform | Looks like scleroderma |

| Cystic | Clear or blue-gray, exude clear fluid if punctured |

| Basosquamous | Behave more like SCC (more aggressive and destructive), increased metastases |

| Micronodular | Infiltrate dermis |

| Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus | Pink plaque on lower back, looks like amelanotic melanoma |

Recurrence and Metastasis Factors

The greatest risk of BCC recurrence has been shown to be within the first 5 years after treatment. Risk factors for recurrence include a tumor diameter greater than 2 cm, location on the central part of the face or ears, long-standing duration, incomplete excision, an aggressive histologic growth pattern, and perineural or perivascular involvement. Tumors with subclinical extension or indistinct borders have a higher recurrence rate than more limited or well-defined tumors. Metastasis of BCC is rare, with metastatic rates ranging from 0.003% to 0.5%. Fewer than 500 cases have been reported in the literature.

Squamous cell carcinoma

SCC is the second most common skin cancer and represents 20% of all NMSC cases. It is estimated that the lifetime risk for developing an SCC in Caucasian men is 9% to 14% and in women, 4% to 9%. A significant rise in the incidence of SCC over the past 2 decades has been documented. SCCs arise from the epidermis with atypical keratinocyte cells that can invade the dermis and progress to metastasize. Unlike BCC, SCC has a significant risk of metastasis and can be fatal.

Pathogenesis

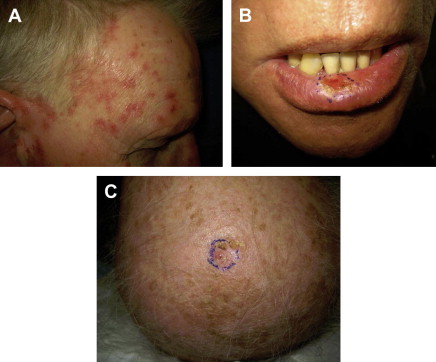

SCC has a classical precursor lesion, the actinic keratosis (AK). AKs are precancerous lesions defined by histologic atypical keratinocytes that do not encompass the entire epidermis. In contrast, an SCC has full-thickness keratinocyte atypia. AKs are one of the most frequently seen lesions in any dermatology practice. They are more common in lighter-skinned persons with a predilection for areas of increased sun exposure including the head, neck, and upper extremities. AK may be identified as rough, erythematous papules with white or yellow scale that are more easily felt than seen ( Fig. 5 ). They are usually in the presence of a background of photodamage to the skin. Approximately 2% to 10% of all AKs evolve into invasive SCC. There is a 10% lifetime risk of a person with multiple AKs to develop a SCC. This risk also depends on the number of AK lesions and the length of time they are present. Options for treating AKs include cryosurgery, electrodessication and curettage, and topical chemotherapy. SCC is believed to derive from a single transformed cell of the keratinocyte lineage in the epidermis. Exposure to UV radiation is the most common cause of SCC. Repetitive UV irradiation hitting vulnerable keratinocytes induces mutations in the DNA of the p53 tumor-suppressor gene, leading to tumor formation. Other factors that lead to the formation of SCC are exposure to ionizing radiation, infection with human papilloma virus, exposure to chemical agents such as arsenic, and intake of immunosuppressive medications as seen in organ transplant recipients. Organ transplant recipients develop SCC more often than BCC in contrast to the general population.

Clinical Presentation

SCCs are identified as an erythematous, pink, scaling plaque, papule, or nodule on sun-exposed skin that may have ulceration ( Fig. 6 ). Lesions can be crusted plaques or firm nodules as well. They most commonly occur on the head and neck, but often occur on the trunk. Patients often describe their lesions as nonhealing wounds that bleed periodically and may or not be painful. SCCs are also more likely to develop in injured skin or in skin that is chronically diseased such as long-standing ulcers, radiation dermatitis, or vaccination scars. These lesions also have a tendency to develop in mucocutaneous sites such as the lip and oral mucosa. SCCs in these areas have increased metastatic potential.

Recurrence and Metastasis Factors

Unlike BCC, SCC is associated with increased metastatic potential and worse prognosis. The 5-year rate of recurrence is 8%, and the 5-year rate of metastasis is 5%. Risk factors for increased recurrence and metastatic potential include large lesions (>2 cm), poorly defined borders, a rapidly growing tumor, poorly differentiated histology, and tumors located on the head and neck but specifically the lip, eyelid, and ear. The presence of immunosuppression and perineural involvement on pathology also increases metastatic risk.

Treatment of NMSC

NMSC is one of the most treatable cancers with an excellent prognosis. However, proper treatment requires the early detection of suspicious lesions and follow-up with a dermatologist, plastic surgeon, or other specialist. As with any medical workup, the primary goal of the dermatologic examination is a thorough history-taking and physical examination. Suspicious lesions are biopsied, and the specimen is then sent for pathologic examination, which ideally will yield a diagnosis and allow for stratification of the lesion according to risk. Following diagnosis, numerous techniques are available for treatment, which can be divided into surgical and nonsurgical ( Table 2 ). Choice of treatment should take into consideration tumor type, location, histologic growth pattern, and whether the tumor is primary or recurrent. Surgical approaches include curettage and electrodesiccation, cryosurgery, surgical excision, and Mohs micrographic surgery. The most frequently used method for treatment of BCC is surgical excision, which has the advantage of histologic evaluation of the margins of the specimen, although vertical processing allows visualization of less than 1% of the entire specimen margin. Mohs micrographic surgery remains the gold standard because of its highest cure rate, complete histologic analysis of tumor margins using horizontal sectioning techniques, and preservation of normal tissue ( Fig. 7 ). Electrodessication and curettage is easy to perform, cost-effective, and cosmetically acceptable; however, cure rates are much less and are highly dependent on technique and experience. Nonsurgical approaches include radiotherapy, topical and injectable therapy, and photodynamic therapy. Radiotherapy is an important option for patients who are not surgical candidates, although its use may be limited because of the risk of side effects. Newer topical therapies such as imiquimod and photodynamic therapy have been shown to be useful for superficial lesions. However, there are few randomized controlled studies comparing different skin cancer treatments, and much of the published literature has low patient numbers and short-term follow-up. Cryosurgery, involving freezing of the lesion with liquid nitrogen, is the mainstay treatment for AKs, the precursor lesion of SCC. Additional nonsurgical treatments include novel topical and intralesional injection therapies using compounds such as 5-fluorouracil. The management of high-risk skin cancers involves a multidisciplinary team of dermatologists, surgical oncologists, medical oncologists, pathologists, transplant physicians, and radiation oncologists.