and Paolo Biondi2

(1)

Aesthetic and Maxillofacial Surgery, Padova, Italy

(2)

Maxillofacial Surgery, Forlì, Italy

9.1.1 Anterior Vertical Excess

9.6.1 Interincisal Angle

9.8.1 Vertical Proportions

9.8.2 Nasofacial Angle

9.8.3 Nasomental Angle

9.8.4 Mentocervical Angle

9.8.5 Submental–Neck Angle

9.8.6 Subnasal Vertical

9.8.7 Nasolabial Angle

Abstract

Dentofacial deformities are of interest to many specializations, even though they are mainly treated by two professional figures who work together: the orthodontist and the maxillofacial surgeon. In the 1960s and 1970s, the prevailing orthodontic view was that “Jaw deformity will inevitably affect the integumental profile of the individual and will lead to a relative imbalance of the nose, lips and chin. Dental occlusion can be used as a reference for defining these distortions” [1]. Such thinking is now xout of date. Today, the dental occlusion is considered as only one component of the deformity, and its normalization with orthodontics and jaw surgery is not synonymous with facial balance and improved aesthetics. For this and other reasons, in many clinical cases, the preoperative analysis and the treatment planning should also be conducted in collaboration with experts in other fields.

Dentofacial deformities are of interest to many specializations, even though they are mainly treated by two professional figures who work together: the orthodontist and the maxillofacial surgeon. In the 1960s and 1970s, the prevailing orthodontic view was that “Jaw deformity will inevitably affect the integumental profile of the individual and will lead to a relative imbalance of the nose, lips and chin. Dental occlusion can be used as a reference for defining these distortions” [1]. Such thinking is now xout of date. Today, the dental occlusion is considered as only one component of the deformity, and its normalization with orthodontics and jaw surgery is not synonymous with facial balance and improved aesthetics. For this and other reasons, in many clinical cases, the preoperative analysis and the treatment planning should also be conducted in collaboration with experts in other fields.

The study of dentofacial deformities is based on three different sequenced analyses:

-

Direct and photographic clinical facial analyses, which dictate the need for surgery to change the facial appearance

-

Intraoral and dental cast analysis, which is necessary to assess the malocclusion in its two components: intra-arch and interarch relationships

-

Cephalometric analysis, which can add new data, measure some parameters, and permit, through the creation of the visualization of treatment objectives, an in-depth study of the effects of jaw surgery on skeletal, dental, and soft tissue spatial position

9.1 The Basic Components of Dentofacial Deformities

Understanding a dentofacial deformity clinical case can be made easier by the identification of its basic components:

-

Anterior vertical excess or deficiency

-

Class III or II sagittal discrepancy

-

Transverse discrepancies and asymmetry

9.1.1 Anterior Vertical Excess

The anterior vertical excess has been given many other terms, such as vertical maxillary excess, hyper divergent skeletal pattern, high-angle case, long face, and skeletal open bite.

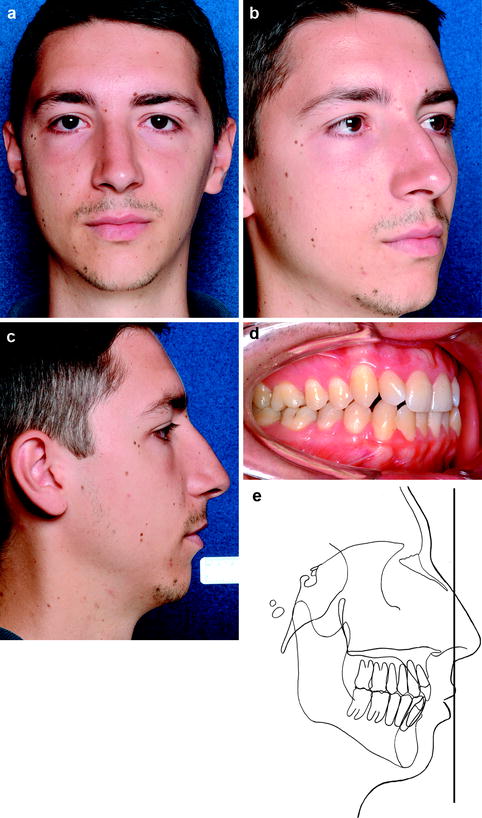

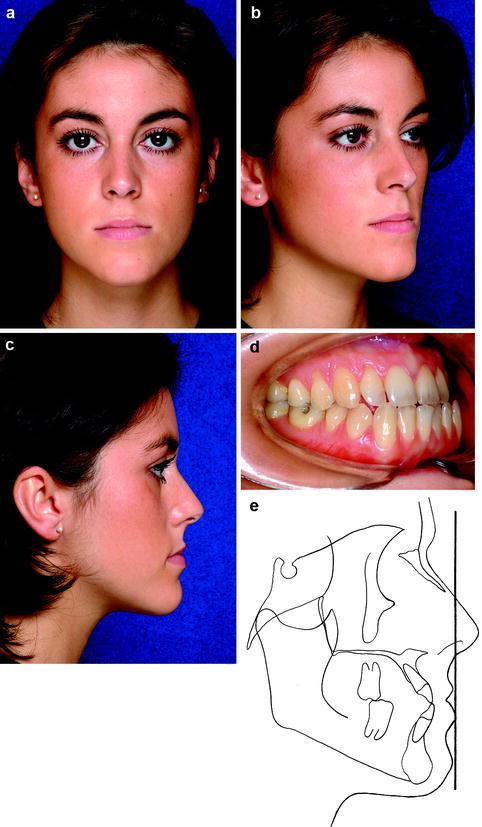

Figure 9.1 shows a clinical case1 in which many of the external morphological and skeletal characteristics of the anterior vertical excess are present. Analyzing the frontal view (Fig. 9.1a), we note a clear elongation of the vertical axis of the face, with a reduction in the facial widths. The mandibular outline is asymmetric at the angles, and a general impression of flatness of the malar, infraorbital, paranasal, cheek, and chin regions is perceived.

Fig. 9.1

A clinical case of anterior vertical excess. Frontal (a), oblique right (b), profile (c), intraoral right views (d), and cephalometric tracing (e)

The oblique view (Fig. 9.1b) confirms the flattening of the malar, infraorbital, cheek, paranasal, and chin regions. In particular, the ogee curve outline, in all its components, is constituted of long and nearly straight tracts joined together with open angles.

The profile view (Fig. 9.1c) adds the following important diagnostic elements:

-

The total anterior facial height is augmented.

-

All the anterior facial thirds appear to be augmented.

-

The flatness of the malar, infraorbital, paranasal, cheek, and chin regions is confirmed.

-

The nose appears to be long.

-

The upper lip outline is clockwise rotated with a lack of anterior projection.

-

The labiomental fold is flat.

-

The mandibular border outline is partially hidden and clockwise rotated.

-

The total chin–throat–neck outline length is reduced with an open cervicomental angle.

The intraoral view (Fig. 9.1d), despite the external facial morphology, shows a molar class I, an anterior dental malocclusion with no anterior open bite.

The cephalometric tracing (Fig. 9.1e), obtained from the cephalograms in the lateral view, permits the correlation of the facial profile with the shape and spatial position of some of the dental and skeletal supporting structure.

9.1.2 Anterior Vertical Deficiency

The anterior vertical deficiency is characterized by the opposite features of the vertical excess and is also called vertical maxillary deficiency, hypodivergent skeletal pattern, low-angle case, short face, and skeletal deep bite.

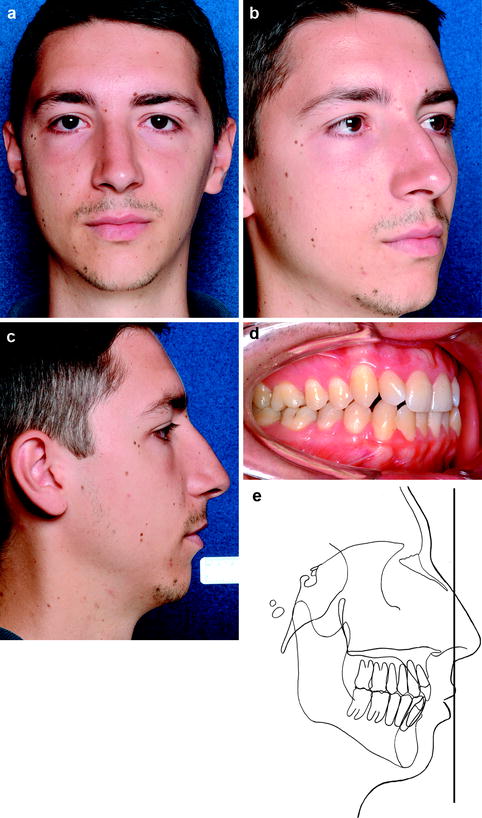

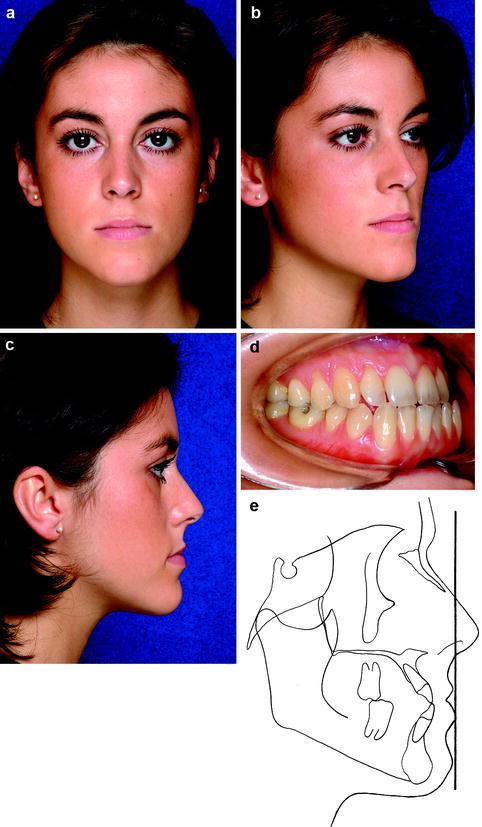

Figure 9.2 shows a clinical case2 in which many of the external morphological, skeletal, and dental characteristics of the anterior vertical deficiency are present. Analyzing the frontal view (Fig. 9.2a), we note a short vertical axis of the face with a large reduction of the lower facial third height and the relative increase of all facial widths.

Fig. 9.2

A clinical case of anterior vertical deficiency. Frontal (a), oblique right (b), profile (c), intraoral anterior views (d), and cephalometric tracing (e)

The oblique view (Fig. 9.2b) confirms the large reduction of the lower face height, also drawing attention to the long and overprojected nose.

The profile view (Fig. 9.2c) confirms and adds some important diagnostic elements such as:

-

Reduction of the lower anterior face height; conversely, the central and upper anterior facial third may appear augmented.

-

The nose appears to be long.

-

The upper lip outline is counterclockwise rotated and excessively concave.

-

The labiomental fold is extremely deep and unnatural.

-

The mandibular border outline is counterclockwise rotated in a nearly horizontal position. This affects the chin projection, which seems to be increased; nevertheless, this is not sufficient to obtain a pleasant cervicomental angle.

-

The throat length is extremely short.

The frontal intraoral view (Fig. 9.2d), according to the external facial morphology, shows the anterior dental deep bite (the lower teeth are totally hidden by the upper incisors and cuspids). The cephalometric tracing (Fig. 9.2e), obtained from the cephalograms in the lateral view, permits the correlation of the facial profile with the shape and spatial position of some of the dental and skeletal supporting structure.

9.1.3 Class III Sagittal Discrepancy

The class III sagittal discrepancy brings together many deformities common to an anteriorly positioned lower third of the face and/or a posterior-positioned middle third.

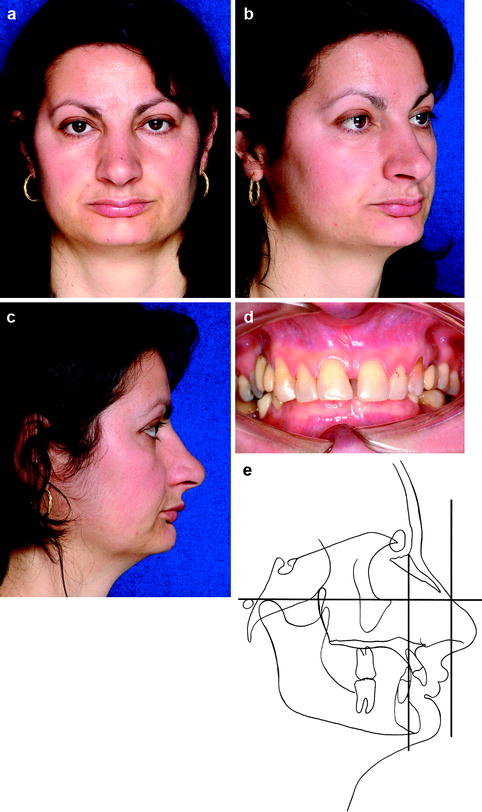

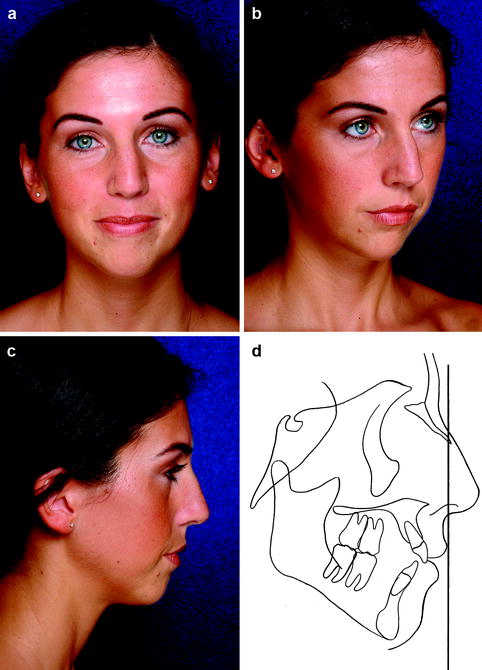

Figure 9.3 shows a clinical case3 in which many of the external morphological, skeletal, and dental characteristics of the class III sagittal discrepancy are present. Analyzing the frontal view (Fig. 9.3a), we note the depressed infraorbital and paranasal regions with a tendency toward an inferior scleral show. The total facial height and the facial widths seem proportioned, whereas a general impression of flatness of infraorbital, paranasal, and cheek regions is perceived.

Fig. 9.3

A clinical case of class III dentofacial deformity. Frontal (a), oblique right (b), profile (c), intraoral right oblique views (d), and cephalometric tracing (e)

The oblique view (Fig. 9.3b) confirms the flattening of the infraorbital, cheek, and paranasal regions; in particular, the ogee curve outline shows the tendency toward a concave face due to midface retrusion.

The profile view (Fig. 9.3c) confirms and adds some important diagnostic elements such as:

-

The total anterior facial height appears to be increased.4

-

The flatness of malar, infraorbital, cheek, and paranasal regions is confirmed.

-

The lower third of the nose appears to be normal in spite of the lack of skeletal support.

-

The upper lip outline is clockwise rotated.

-

The chin is slightly overprojected.

-

The labiomental fold is normally shaped.

-

The mandibular border outline is well defined and clockwise rotated.

-

The total chin–throat–neck outline length, as well as the cervicomental angle definition and degree, are pleasing.

The oblique right intraoral view (Fig. 9.3d) shows a dental malocclusion with molar and canine class III, partial anterior reverse overjet, and anterior dental crowding of the lower anterior teeth.

The cephalometric tracing (Fig. 9.3e), obtained from the cephalograms in the lateral view, permits the correlation of the facial profile with the shape and spatial position of some of the dental and skeletal supporting structure.

9.1.4 Class II Sagittal Discrepancy

The class II sagittal discrepancy brings together many deformities common to a posteriorly positioned lower third of the face (more frequent) and/or an anteriorly positioned middle third (less frequent).

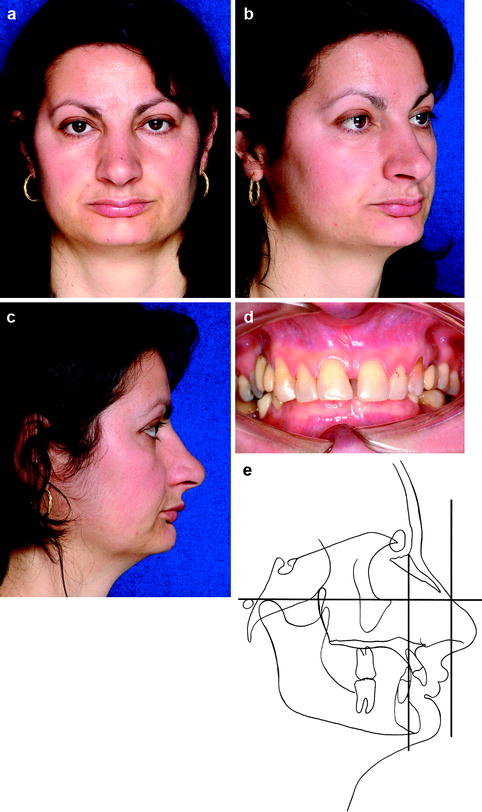

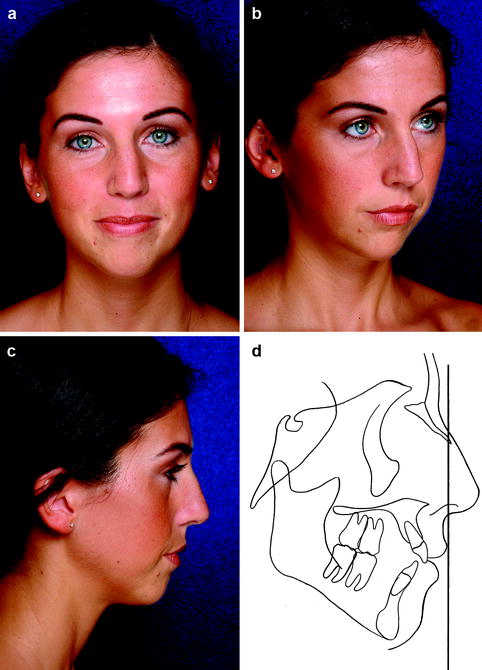

Figure 9.4 shows a clinical case5 in which many of the external morphological, skeletal, and dental characteristics of the class II sagittal discrepancy are present. Analyzing the frontal view (Fig. 9.4a), we note an evident facial asymmetry, a large and deviated nose, and a reduced chin width.

Fig. 9.4

A clinical case of class II dentofacial deformity. Frontal (a), oblique right (b), profile views (c), and cephalometric tracing (d)

The right oblique view (Fig. 9.4b) reveals the flat malar, infraorbital, cheek, paranasal, and chin regions. The ogee curve outline, in this particular case, helps the observer to recognize the extreme grade of the chin underprojection.

The profile view (Fig. 9.4c) adds the following important diagnostic elements:

-

The facial profile is convex, which is primarily due to the clockwise overrotated mandible.

-

The flatness of the malar, infraorbital, cheek, paranasal, and chin regions is confirmed.

-

The upper lip outline is slightly clockwise rotated.

-

The labiomental fold is flat.

-

The chin is severely underprojected.

-

The mandibular border outline is clockwise rotated.

-

The total chin–throat–neck outline length is reduced with an open cervicomental angle.

-

The throat length is extremely short. The cephalometric tracing (Fig. 9.4d), obtained from the cephalograms in lateral view, shows the presence of overjet between the upper and lower incisors, as well as the molar class II relationship, and confirms the clockwise rotation of the mandible and the chin underprojection.

9.1.5 Transverse Discrepancies and Asymmetry of the Jaws

An asymmetric arrangement of the dental arches is frequently associated with a corresponding facial asymmetry. The clinical case presented in Fig. 8.5 in the previous chapter is a clear example of that association. Analyzing the frontal and left views of the dental cast (Fig. 8.5a, b), we note these points:

-

The mandibular midline is deviated on the left compared to that of the maxillary.

-

Some teeth on the left side (colored in Fig. 8.5b) are in a reverse overbite relationship.

-

The line connecting the two lower cuspids as well as the occlusal plane of the mandibular arch is counterclockwise rotated.

The facial frontal view (Fig. 8.5c) confirms that the facial asymmetry is coherent with the intraoral findings. In particular:

-

The line connecting the two labial commissures is tilted counterclockwise.

-

The chin is deviated to the left.

Figure 8.5c also shows some reference planes utilized in the assessment of the facial asymmetries, such as the lines connecting the medial canthus, the upper palpebral folds, or the apex of the eyebrows. Each of these lines must be checked in order to confirm their symmetry and therefore their reliability.

9.1.6 The Immense Number of Combinations of Different Types and Grades of the Basic Components of Facial Deformities

In a real clinical situation, there is almost never an isolated basic component of a facial deformity in a patient, and the grade of the deformity also varies greatly.

The real cases presented here in Figs. 9.1, 9.2, 9.3 and 9.4 and in Fig. 8.5 for demonstration purposes have one weak point: they are without doubt a mix of these basic components, so the preoperative clinical analysis still is not finished with the understanding of the most obvious element but must continue until a complete assessment of the case is done.

Nevertheless, in the initial steps of the analysis, any written notes should be based on the clinical assessment without taking precise metric or angular measurements. At this early stage, a rigid “computerized” method of analysis, with its normative values, must be avoided.

9.2 Direct and Photographic Clinical Analysis for Dentofacial Deformities

The biggest mistake we can make, when dealing with dentofacial deformities, is to limit our attention only to the jaw relationships. A severely retruded maxilla, for example, profoundly influences the aesthetics of the lower lids, zygomatic and orbital, nasal and paranasal, upper and lower lips, mandibular, and chin regions. For that reason, before continuing to read this chapter, I suggest that the reader should be familiar with the basic facial analysis (Chap. 5), the eyes and orbital analysis (Chap. 6), the nasal analysis (Chap. 7), and the lips, teeth, chin, and smile analysis (Chap. 8); furthermore, some points reported in the previous analysis checklists must be incorporated into the dentofacial analysis checklist.

When dealing with dentofacial deformities, during examination and photographic documentation, it is extremely important to obtain a relaxed lip position, a relaxed-rest mandibular position, and again the natural head position. How to obtain the natural head position is described in Chap. 3. In order to help the patient achieve the relaxed lip position, the examiner asks him to relax, strokes the lips gently, and takes multiple pictures on different occasions; an additional assessment of the lips is obtained with successive casual observations while the patient is unaware of being observed [2, 4].

Some authors [2, 13, 14] favor performing the direct and photographic analysis in centric relationship or centric occlusion, which means maintaining the two dental arches in contact, with the mandibular elevator muscles contracted. I disagree with this because normally a person is only in this position while swallowing, obtaining it for a fraction of a second. Maintaining it for a minute is a difficult task for patients because of the need for continuous muscle strain and the unnatural mandibular position.

Instead, for my basic aesthetic considerations, I want a relaxed position of the mandible in every case, doing a further facial examination in the close bite position only if a large difference in soft tissue arrangement exists between the two, as shown in Fig. 9.5.

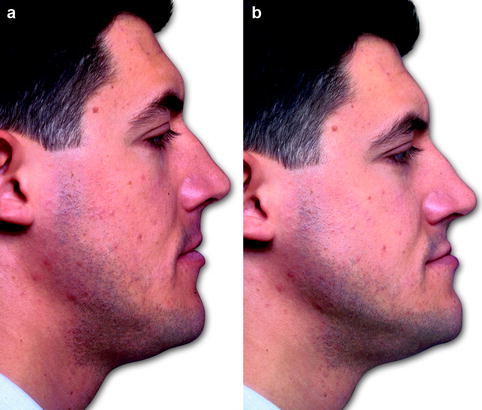

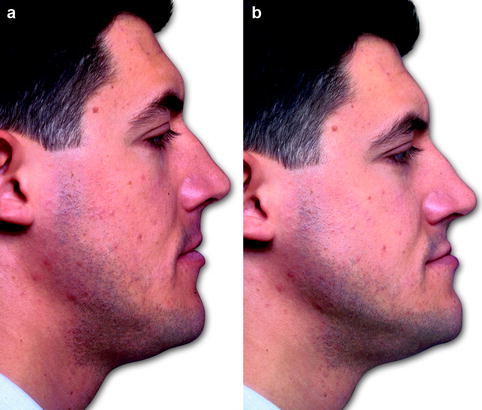

Fig. 9.5

Differences in facial soft tissue adjustment in the same subject in his habitual posture (a) and in the close bite mandibular position (b). The patient obtains the latter condition only during the act of swallowing

As a general rule, in the clinical assessment of the total and regional vertical facial heights, it is possible to highlight more or less pronounced curves and more or less acute angles. In particular, the long face in profile and oblique views can be seen as an open accordion (Fig. 9.6a) with obtuse angles and flat curves, whereas a short face can resemble a closed accordion (Fig. 9.6b) with acute angles and pronounced curves.

Fig. 9.6

The long face in profile and oblique views can be seen as an open accordion (a) with obtuse angles and flat curvatures, whereas the short face can resemble a closed accordion (b) with acute angles and pronounced curves

Particular attention should be given to the cheekbone–nasal base–lip curve contour described by Arnett and Bergman [3]. In a subject with good facial proportions, it is composed of a convex, anteriorly facing, uninterrupted line that starts just anterior to the ear, follows the zygomatic arch, passing through the cheekbone point, extending anterorinferiorly reaching the maxilla point, which constitutes its most anterior point, and then ending lateral to the commissure of the mouth (Fig. 9.7).

Fig. 9.7

The cheekbone–nasal base–lip curve contour described by Arnett and Bergman in frontal (a), oblique (b), and profile views (c) of a subject with good facial proportions. The cheekbone point, in a subject with good facial proportions, is the apex of osseous cheekbone that is located 20–25 mm inferior and 5–10 mm anterior to the outer canthus of the eye when viewed in profile and is 20–25 mm inferior and 5–10 mm lateral to the outer canthus of the eye when viewed frontally. A flat cheekbone point is often associated with malar deficiency and maxillary hypoplasia. The maxilla point is the most anterior point on the continuum of the cheekbone–nasal–lip contour described by Arnett and Bergman and is an indicator of maxillary anteroposterior position [3]

A maxillary retrusion is clinically related to a straight or concave cheekbone–nasal base–lip curve contour at maxilla point, a flat cheekbone point, and a clockwise rotation of the lower lid inclined in profile view, whereas the ogee profile on oblique view shows a flat outline at the level of the malar eminence (Fig. 9.8).

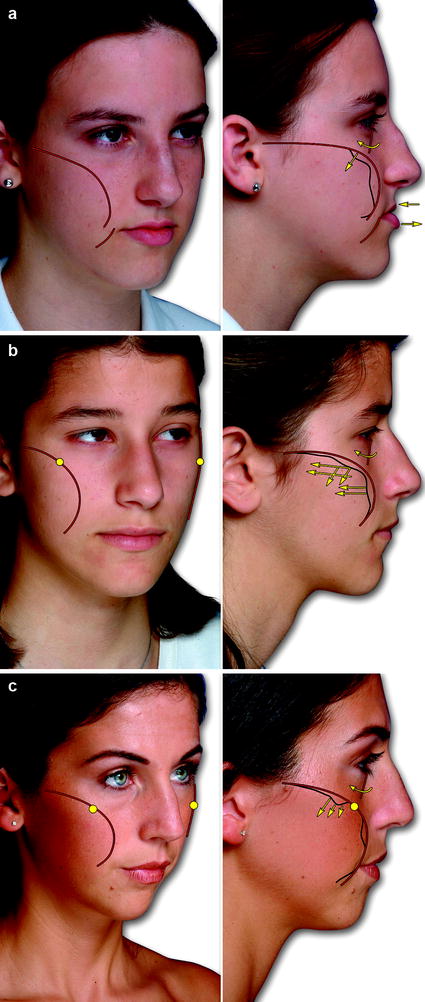

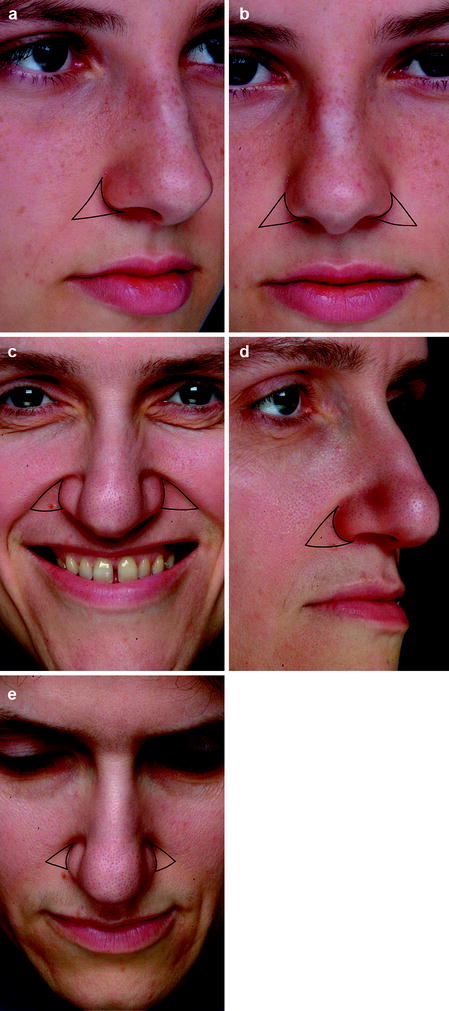

Fig. 9.8

Profile and oblique views of three subjects (a–c) with maxillary retrusion in which the cheekbone–nasal base–lip curve contour displays a flat cheekbone point, a posterior positioned maxillary point, and a clockwise rotation of the right lower lid incline in profile view, whereas the ogee profile on oblique view shows a flat outline at the level of the malar eminence

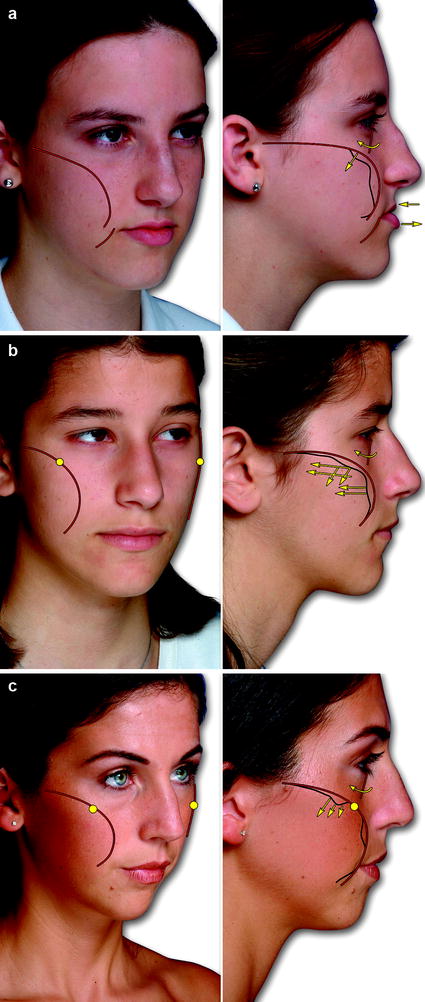

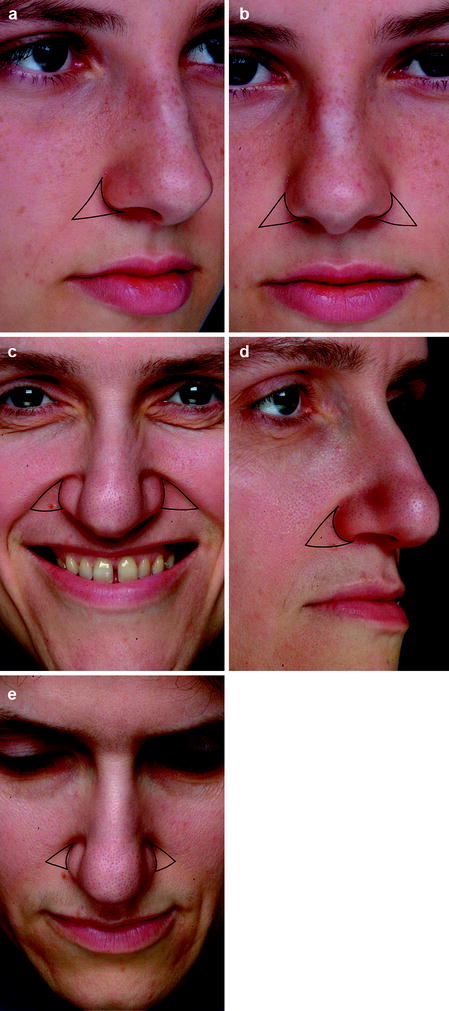

Utilizing the frontal and oblique views, further attention should be given to the triangular area situated between the nasal base at the alar crease junction and the upper end of the nasolabial sulcus, the paranasal triangle, evaluating its depth. Again, a maxillary hypoplasia is associated with a deep paranasal triangle (Fig. 9.9).

Fig. 9.9

Assessment of the paranasal triangle. In these two cases, the maxillary hypoplasia is associated with a deep paranasal triangle, the triangular area situated between the nasal base at the alar crease junction and the upper end of the nasolabial sulcus (a–e)

In order to visualize the relationship between the maxillary anteroposterior position, the nasal tip projection, and the chin projection better, I suggest drawing three angles over the life-size profile view photograph. The first is the angle obtained by connecting glabella, nasal tip, and soft tissue pogonion (G′-P-Pog′); the second is the angle obtained by connecting glabella, subnasale, and soft tissue pogonion (G′-Sn-Pog′), also called the angle of facial convexity; and the third is the angle obtained by connecting glabella, alar crease junction, and soft tissue pogonion (G′-ACJ-Pog′). Even if I do not measure these angles, simple observation of the drawing helps in finding and differentiating the anteroposterior relationships of the maxilla, chin, nasal tip, and anterior nasal spine, as shown in the clinical examples in Fig. 9.10.

Fig. 9.10

In these profile views of six different cases, three angles are superimposed. The first is the angle obtained by connecting glabella, nasal tip, and soft tissue pogonion (G′-P-Pog′); the second is the angle obtained connecting glabella, subnasale, and soft tissue pogonion (G′-Sn-Pog′), also called the angle of facial convexity; and the third is the angle obtained connecting glabella, alar crease junction, and soft tissue pogonion (G′-ACJ-Pog′). A normal maxilla may be associated with a slight overprojected nasal tip (a) or an overprojected chin (b), whereas a hypoplasic nasal base and maxilla may be associated with a normal nasal tip and chin projection (c), an overprojected nasal tip (d), an underdeveloped nasal spine (e), and an overprojected nasal tip and a mandibular retrusion (f)

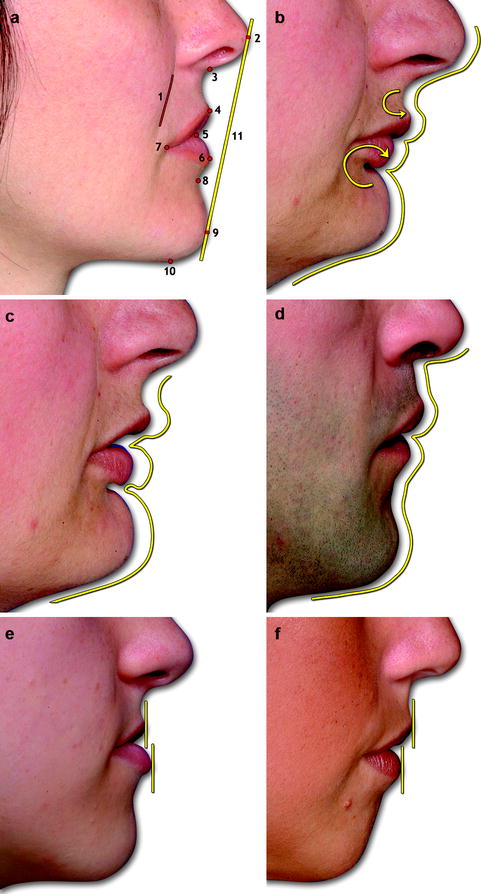

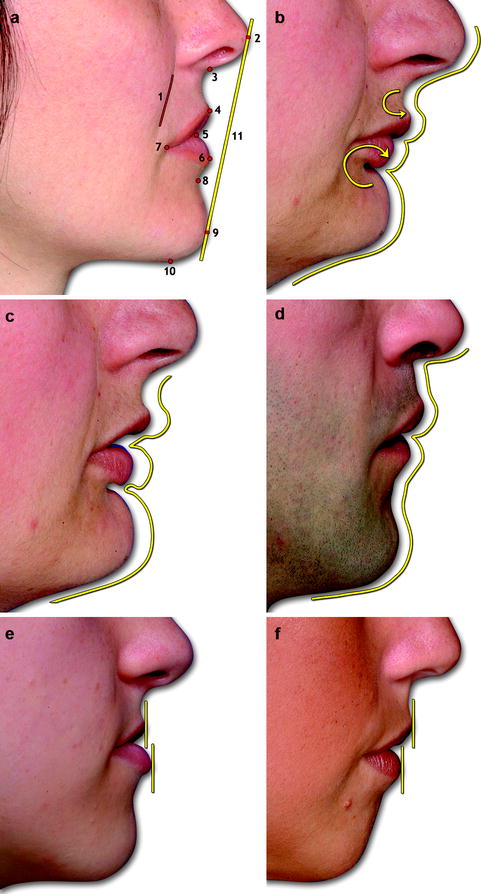

The lip outline is evaluated considering the maxillary and mandibular sulcus contours, which should be two gentle concavities [3], as well as the anteroposterior relationship between the labrale superior and inferior, whose projection should differ minimally (Fig. 9.11).

Fig. 9.11

The upper and lower lip outline should be two gentle curves with minimal differences in anteroposterior projection (reference points and Ricketts’ lips projection reference E-line: 1 nasolabial sulcus, 2 nasal tip, 3 subnasale, 4 labrale superior, 5 stomion, 6 labrale inferior, 7 lip commissure, 8 labiomental sulcus, 9 soft tissue pogonion, 10 soft tissue menton, 11 Ricketts’ E-line) (a). In a skeletal anterior vertical deficiency case, either in close bite (b) or in mandibular rest position (c), the lip outline contours present deep curves, whereas in anterior vertical excess, the lip outline contours present flat curves (d). In a skeletal class III discrepancy case, the labrale inferior is usually in front of the labrale superior (e) and vice versa for a skeletal class II discrepancy case (f)

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses