Patients who have developmental disabilities and epilepsy can be safely treated in a general dental practice. A thorough medical history should be taken and updated at every visit. A good oral examination to uncover any dental problems and possible side effects from antiepileptic drugs is necessary. Stability of the seizure disorder must be taken into account when planning dental treatment. Specific considerations for epileptic patients include the treatment of oral soft tissue side effects of medications and damage to the hard and soft tissue of the orofacial region secondary to seizure trauma. Most patients who have epilepsy can and should receive functionally and esthetically adequate dental care.

The term “epilepsy” refers to a group of neurologic disorders characterized by chronic, recurrent, paroxysmal seizure activity. The word epilepsy is derived from the Greek word epilambanein , meaning to attack or seize. In the past, epilepsy was associated with religious experiences and even demonic possession. In ancient times, epilepsy was known as the “sacred disease” because people thought that epileptic seizures were a form of attack by demons, or that the visions experienced by persons who had epilepsy were sent by the gods. In 400 bc , Hippocrates recognized that epilepsy was a brain disorder, and he spoke out against the ideas that seizures were a curse from the gods and that people who had epilepsy held the power of prophecy. The foundation of our modern understanding of the pathophysiology of epilepsy was proposed in 1873 by London neurologist John Hughlings Jackson, who proposed that seizures were the result of sudden brief electrochemical discharges in the brain. He also suggested that the character of the seizures depended on the location and function of the site of the discharges.

Incidence and prevalence

Epilepsy is a common chronic neurologic disorder that is characterized by recurrent unprovoked seizures. A seizure is the result of spontaneous, synchronous, inappropriate, and excessive electric discharge of cerebral neurons that interfere with the normal function of the brain and result in alterations in level of consciousness, convulsive movements or other motor activity, sensory phenomena, behavioral abnormalities, and mental impairment. Approximately 10% of Americans will experience a seizure in their lifetime. Most of these seizures are attributable to a specific cause, such as a high fever or underlying metabolic disorder. Isolated seizures are most common during childhood, with as many as 4% of children having at least one seizure before the age of 15. However, an isolated seizure does not indicate epilepsy. Epilepsy, in contrast, is a recurrent illness, and the patient must have at least two seizures before a diagnosis of epilepsy is considered.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, epilepsy is one of the most commonly diagnosed neurologic disorders. The overall incidence of epilepsy, excluding febrile convulsions and single seizures, is generally about 50 cases per 100,000 persons per year (range 40–70 per 100,000 per year) in developed countries. Approximately 1% of the United States population, or 2.7 million people, have epilepsy. The incidence of this disorder is highest in patients younger than 2 years of age and rises again after 65 years of age. More than 20% of cases are discovered before a child is 5 years of age. In infants, birth injuries and congenital defects are the primary causes of epilepsy. Birth injuries, genetic factors, infections, and trauma are major contributing factors in children and adolescents from 2 to 20 years of age. For individuals between 20 and 30 years of age, brain tumors and other structural lesions are the foremost contributing causes. In those older than 50 years of age, cerebral vascular accidents and metastatic tumors are significant causes of seizure activity.

Developmental disabilities and epilepsy in children and adults

Epilepsy is the most common comorbid medical condition in persons who have developmental disabilities. Epilepsy occurs more frequently (25%–35%) in people who have neurologic-based disabilities. The relationship between the cause of the disability and epilepsy may be complex, although in most cases, a single underlying brain abnormality or insult to the brain causes both disorders and is another manifestation of brain injury or differences in brain development. Epilepsy occurs in 15% to 55% of children and adults who have cerebral palsy, depending on the form of cerebral palsy and the severity of motor deficit. Approximately 20% to 30% of children and adolescents who have autism develop some form of epileptic disorder. The pathophysiology of epilepsy is related to the cause of the brain damage in patients who have mental retardation. The frequency and the severity of the epileptic syndrome are related more to the primary cause of mental retardation than to the severity of mental retardation. The prevalence of mental retardation is approximately 0.3% to 0.8%, but 20% to 30% of children who have mental retardation have epilepsy. Sixty-nine percent of children who have epilepsy and mental handicap have a secondary handicap such as cerebral palsy, autism, or visual impairment. Approximately 35% to 40% of children who have epilepsy also have mental retardation and up to 71% of people who have mental retardation and cerebral palsy have epilepsy. The severity of intellectual disability and the frequency and severity of chronic epileptic seizures are directly related. The rate is around 20% in persons who have mild intellectual impairment and can be as high as 50% in those who have severe-to-profound intellectual disability. Epileptic seizures in adults in their late 40s who have Down syndrome are seen as an expression of Alzheimer disease, which occurs with greater frequency in individuals who have Down syndrome than in the general population. The epileptic disorders in patients who have mental impairment or developmental disability are usually complex, involving more than one seizure type, and are often more severe and difficult to control than disorders in the general population. Individuals who have developmental disabilities and epilepsy have higher rates of seizure recurrence after a first seizure, lower rates of “outgrowing” epilepsy, a higher degree of morbidity associated with frequent accidents and fractures, and higher rates of sudden unexpected death.

Developmental disabilities and epilepsy in children and adults

Epilepsy is the most common comorbid medical condition in persons who have developmental disabilities. Epilepsy occurs more frequently (25%–35%) in people who have neurologic-based disabilities. The relationship between the cause of the disability and epilepsy may be complex, although in most cases, a single underlying brain abnormality or insult to the brain causes both disorders and is another manifestation of brain injury or differences in brain development. Epilepsy occurs in 15% to 55% of children and adults who have cerebral palsy, depending on the form of cerebral palsy and the severity of motor deficit. Approximately 20% to 30% of children and adolescents who have autism develop some form of epileptic disorder. The pathophysiology of epilepsy is related to the cause of the brain damage in patients who have mental retardation. The frequency and the severity of the epileptic syndrome are related more to the primary cause of mental retardation than to the severity of mental retardation. The prevalence of mental retardation is approximately 0.3% to 0.8%, but 20% to 30% of children who have mental retardation have epilepsy. Sixty-nine percent of children who have epilepsy and mental handicap have a secondary handicap such as cerebral palsy, autism, or visual impairment. Approximately 35% to 40% of children who have epilepsy also have mental retardation and up to 71% of people who have mental retardation and cerebral palsy have epilepsy. The severity of intellectual disability and the frequency and severity of chronic epileptic seizures are directly related. The rate is around 20% in persons who have mild intellectual impairment and can be as high as 50% in those who have severe-to-profound intellectual disability. Epileptic seizures in adults in their late 40s who have Down syndrome are seen as an expression of Alzheimer disease, which occurs with greater frequency in individuals who have Down syndrome than in the general population. The epileptic disorders in patients who have mental impairment or developmental disability are usually complex, involving more than one seizure type, and are often more severe and difficult to control than disorders in the general population. Individuals who have developmental disabilities and epilepsy have higher rates of seizure recurrence after a first seizure, lower rates of “outgrowing” epilepsy, a higher degree of morbidity associated with frequent accidents and fractures, and higher rates of sudden unexpected death.

Classification of seizures

In 1981, the International League Against Epilepsy developed an international classification of epileptic seizures based on clinical and electroencephalographic (EEG) features of the seizure. All seizures are broadly divided into two major classes: partial seizures and generalized seizures. Partial seizures are further divided into simple and complex. Unclassified seizures are difficult to fit into a single class ( Box 1 ). The clinical signs or symptoms of seizures depend on the location of the epileptic discharges in the cortex and the extent and pattern of the propagation of the epileptic discharge in the brain. Many patients will have more than one type of seizure and the features of each type of seizure may change from seizure to seizure or over time.

-

Partial seizures

-

Simple partial seizures (consciousness not impaired)

-

Complex partial seizures (with impairment of consciousness)

-

Secondarily generalized seizures

-

Generalized seizures

-

Absence seizures

-

Myoclonic seizures

-

Clonic seizures

-

Tonic seizures

-

Tonic clonic seizures

-

Atonic seizures

-

Unclassified epileptic seizures (incomplete or inadequate data)

Data from Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. Proposal for revised clinical and electroencephalographic classification of epileptic seizures. Epilepsia 1981;22:489–501.

Partial seizures

Partial, or focal, seizures are the more common classification and occur in 75% to 80% of patients who have epilepsy. In contrast to generalized seizures, partial seizures begin focally with an abnormal electric discharge in a restricted region of the brain. Partial seizures are subclassified by their effect on consciousness, responsiveness, and memory as simple partial seizures (patient remains conscious), complex partial seizures (patient has impaired consciousness), or partial seizure evolving to secondarily generalized tonic-clonic seizures.

Simple partial seizures are the most spatially restricted of the partial seizures and are characterized by an episode of altered sensation, cognitive function, or motor activity during which consciousness and ability to interact with the external environment are not impaired. They are also known as “auras” if they precede a complex or secondarily generalized seizure. Symptoms vary, depending on the brain region involved, and can have motor signs (movement of any body part), sensory signs (visual or olfactory changes), psychic signs (fear, anxiety, déjà-vu), or autonomic signs (dizziness, tachycardia, sweating).

Complex partial seizures are defined by an episode of impaired consciousness with altered behavior, sensation, or motor activity that can last from 30 seconds to 2 minutes. The motor activity may consist of repetitive automatic movements of the face or limbs. Partial seizures with secondary generalization occur when the seizure initially localized to one limited area spreads to involve both sides of the brain and evolves into a tonic-clonic or “grand mal” seizure.

Generalized seizures

Generalized seizures begin with a widespread, excessive electric discharge involving most or all of the brain at the same time. They are divided into several types, including absence, myoclonic, atonic, tonic, clonic, and tonic-clonic.

The clinical signs of a generalized tonic-clonic (or grand mal) seizure are well recognized. An aura (a sensory alteration) precedes the convulsion in 35% of patients. The aura is followed by an abrupt loss of consciousness, often accompanied by an “epileptic cry” caused by air being forced out by the contraction of the diaphragm through a partially closed glottis. During the tonic phase (10–15 seconds), the whole body stiffens as the entire musculature contracts forcibly and patients may become cyanotic, tachycardic, and hypertensive. The clonic phase that follows is characterized by simultaneous rhythmic jerking of the arms and legs, usually lasting at least 1 minute. Loss of bladder control is common and patients may bite their tongues, cheeks, or lips. After this type of seizure, the patient typically enters a “postictal” state of confusion and fatigue lasting 30 minutes or longer. Tonic-clonic seizures that last more than 5 minutes or recur in a series of two or more without a return to consciousness indicate a serious neurologic emergency called status epilepticus, which requires immediate medical attention because of airway impairment and aspiration. Supplemental oxygen followed by the administration of a parenteral benzodiazepine such as diazepam or midazolam should be followed by transportation to a hospital emergency department.

Absence (petit mal) seizures are brief episodes of altered or impaired consciousness, unresponsiveness, and cessation of activity. No aura occurs and patients will have a brief episode of staring, usually lasting less than 10 seconds, sometimes associated with blinking or automatic movements of the hands or mouth and autonomic changes such as pallor, tachycardia, or salivation. Atypical absence seizures, which occur in patients who have symptomatic generalized epilepsies, are usually longer than typical absences and often have more gradual onset and resolution. These seizures usually occur in children who also have other types of seizure, lower than average intelligence, and more poorly controlled epilepsy.

Myoclonic seizures are characterized by a brief jerk or series of jerks that may involve a small part of the body, such as a single finger, hand, or foot, or may involve both sides of the body simultaneously, most often the shoulders or upper arms. They are generally of short duration and have no postictal phase. Atonic seizures, or drop seizures, manifest as a sudden loss of muscle tone throughout most or all of the body, which may include head nodding or limb dropping, or the patient collapsing to the ground. Clonic seizures are rhythmic, jerking movements of body parts, such as the arms or legs, with impaired consciousness that occur frequently in people who have focal epilepsy. Tonic seizures are characterized by a stiffening of the body or limb, often resulting in a fall if the patient is standing. These seizures have the highest risk for traumatic injury to the head, oral, and dental structures secondary to falling and forced contraction of the jaws. Tonic seizures last 5 to 20 seconds and are followed by a postictal state.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of epilepsy requires the presence of recurrent, unprovoked seizures. Patients presenting with seizures should have a general and neurologic examination, looking for other causes of loss of consciousness (eg, cardiac abnormalities, evidence of infection), contributing factors or secondary causes of epilepsy, and focal neurologic signs. Some of the important clinical findings include alterations in consciousness, sensation, motor abilities, and reflexes. Detailed accounts of the seizures from either the patient or eyewitnesses can be important in making a correct diagnosis. If seizures are due to an underlying disorder, these conditions are often discovered during the physical examination ( Box 2 ).

-

Conditions most likely to be confused with generalized seizures

-

Syncope

-

Concussive seizures

-

Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures

-

Hypoglycemia

-

Breath-holding attacks

-

Narcolepsy

-

Panic attacks/hyperventilation

-

Toxic or metabolic disturbances

-

Conditions most likely to be confused with partial seizures

-

Transient ischemic attacks

-

Transient global amnesia

-

Vertigo

-

Migraine

-

Movement disorders (eg, tics)

All patients presenting with new-onset seizures should have blood taken for full blood count and biochemistry (urea and electrolytes, blood sugar, calcium, and liver function tests). They should also have an ECG to look for underlying cardiac abnormality and to exclude such conditions as long QT syndrome and other cardiac arrhythmias. Patients in whom focal neurologic signs are found in the absence of a known cause should undergo urgent neuroimaging.

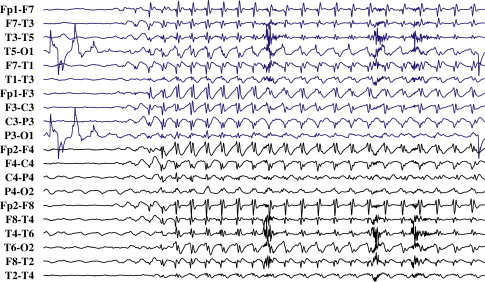

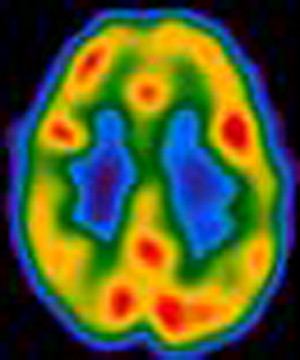

The EEG, combined with the clinical picture, is central to the diagnosis of epilepsy. Seizures produce characteristic spike wave patterns on EEG ( Fig. 1 ). EEG changes observed in persons who have mental retardation and epilepsy are, in general, similar to the ones observed in individuals who have epilepsy without mental retardation. Because the EEG is usually normal when the patient is not having a seizure, methods such as sleep deprivation, hyperventilation, or continuous monitoring using closed-circuit television videotaping and digitized EEG telemetry might be used to increase the chance of capturing abnormal activity. Other imaging and measurement technologies, such as MRI, single photon emission computed tomography, positron emission tomography, and magnetoencephalography, may be useful to discover a cause for the epilepsy, to discover the affected brain region, or to classify the epileptic syndrome, but these studies are not useful in making the initial diagnosis ( Fig. 2 ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses