Noonan syndrome is a developmental disorder characterized by a dysmorphic facial structure, short stature, and mild mental retardation, with associated cardiac defects and skeletal malformations. It may be sporadic or inherited as an autosomal dominant or recessive trait. The incidence of occurrence is 1 in 1000 to 2500 live births. The responsible gene is located on the long arm of chromosome 12. Diagnosis of the syndrome is made by both clinical inspection and karyotype. This is the case report of a 10-year-old Mexican boy who was referred for correction of orofacial and occlusal defects.

Highlights

- •

A multidisciplinary team will establish objectives and treatment decisions accordingly.

- •

Specific objectives for the face, the skeletal pattern, and the dentition were considered.

- •

Enough growth potential was the key to successfully correct this type of severe malocclusion.

- •

An efficient Class II force system is necessary to correct severe vertical and sagittal discrepancies.

Noonan syndrome is characterized by a wide spectrum of congenital heart and pulmonary defects, multiple skeletal defects (chest and spine), a broad or webbed neck, cryptorchidism, and bleeding anomalies. Although a differential diagnosis of this syndrome is difficult, the craniodentofacial structures show specific findings that can be diagnosed by a dental specialist. This case report describes the implications of this syndrome from an orthodontic viewpoint.

The facial construct includes a broad forehead, prominent eyes, hypertelorism, hooded eyelids, down-slanting palpebral fissures, low-set posteriorly rotated ears with a thick helix, and a bulbous tip of the nose with a wide base and thick lips. Orthodontically, a severe maxillomandibular discrepancy is common. Additionally, there is normally a long face (hyperdivergence), micrognathia, excessive gingival display at smile, high arched palate, an open bite or an increased overjet, Bolton discrepancies, oligodontia, and dental deformities.

Diagnosis and etiology

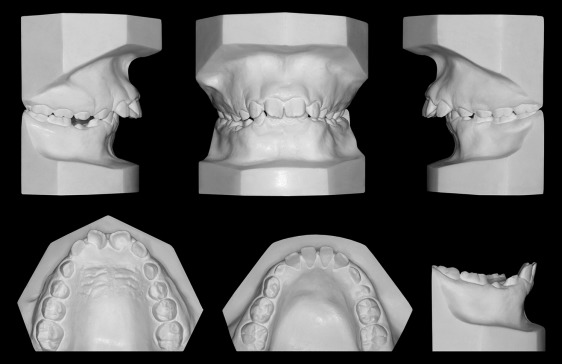

A Mexican boy with Noonan syndrome, aged 10 years 2 months, was seen for evaluation of his dentofacial appearance. After a careful clinical evaluation, he was referred to a geneticist, who performed a karyotype assessment to confirm the syndrome. The patient had systemic issues such as short stature, a slight mental delay, heart trouble, otitis, language disturbances, and asymmetry of the lower limbs. He had a significant tongue thrust habit and a symmetrical face with severe lip incompetence. When smiling, he showed full incisor display and excessive gingival tissues. He had a convex profile with excessive vertical facial dimension and a very recessive chin ( Fig 1 ). The dental casts showed a Class II Division 1 malocclusion. Overjet was 12 mm, and overbite was 7 mm. The midlines were centered. The maxillary arch form was oval with a deep and constricted palatal vault. In the mandibular arch, there was moderate spacing in the anterior area. Some deciduous teeth remained in both arches, and all permanent teeth had shape and size deformities ( Figs 1 and 2 ).

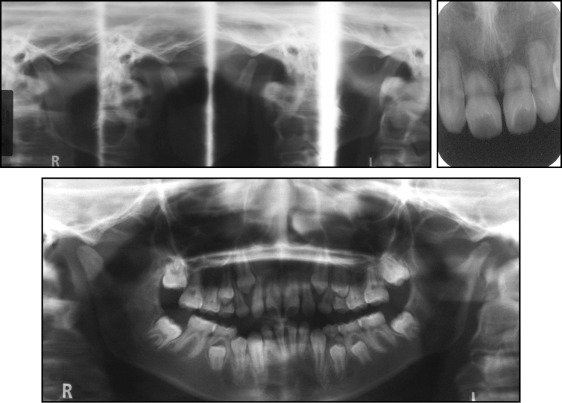

The panoramic radiograph showed congenitally missing maxillary second premolars, short root lengths of all permanent teeth, and resorption in both condyles. Range of motion and amount of opening were normal ( Fig 3 ).

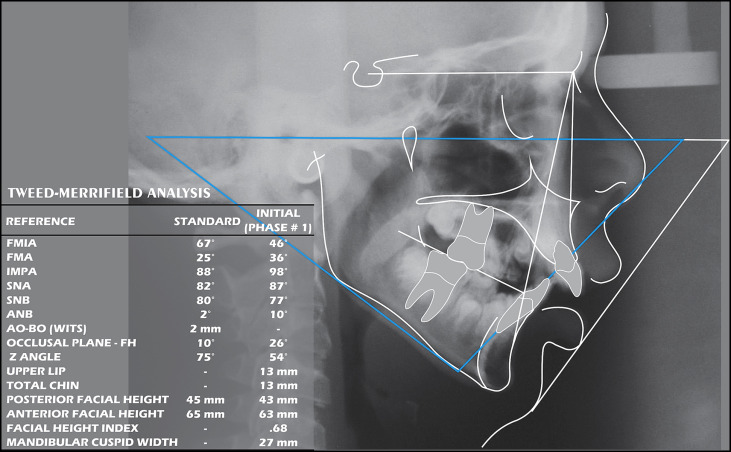

Skeletally, the patient had a severe maxillomandibular discrepancy (ANB angle, 10°). The maxilla was prognathic, and the mandible was mildly retrognathic. The FMA and the facial index confirmed a hyperdivergent growth pattern ( Fig 4 ). Both the maxillary and mandibular incisors were proclined. A steep occlusal plane and a 4-mm curve of Spee added to the complexity of the problem. This severe malocclusion was the result of the genetic disorder and the tongue thrust.

A diagnosis was devised by using the differential diagnostic analysis system and Merrifield’s “dimensions of the dentition” concept. The craniodentofacial total difficulty index for this patient was 231, a number that confirms a severe problem.

Treatment objectives

Treatment objectives for this patient included obtaining a balanced profile, improving function by arranging the teeth to achieve optimal efficiency and an Angle Class I occlusion with normal overbite and overjet, and improving the health of the dentition, jaws, joints, and periodontal tissues. The teeth would be positioned and arranged for maximum stability.

Treatment objectives

Treatment objectives for this patient included obtaining a balanced profile, improving function by arranging the teeth to achieve optimal efficiency and an Angle Class I occlusion with normal overbite and overjet, and improving the health of the dentition, jaws, joints, and periodontal tissues. The teeth would be positioned and arranged for maximum stability.

Treatment alternatives

Five treatement alternatives were considered.

- 1.

Extract the maxillary deciduous canines and first molars, and the mandibular deciduous molars; enucleate the maxillary first premolars and the mandibular second premolars; and then use comprehensive orthodontic treatment to correct the Class II malocclusion.

This approach would eliminate some “bad” teeth (mandibular second premolars) and help with vertical and sagittal discrepancies, and efficient overjet and overbite reduction could be accomplished. However, the space would have to be carefully managed.

- 2.

Extract the maxillary deciduous canines and first molars, and the mandibular deciduous molars; enucleate the maxillary first premolars; and follow with comprehensive orthodontic treatment to correct the canine position.

This plan offered efficient overjet and overbite reduction but would require moving all maxillary anterior teeth distally without anchorage loss.

- 3.

Combine orthodontic treatment with orthognathic surgery (LeFort I impaction, mandibular advancement and genioplasty). This option would produce a better facial result, but the risks of surgery would need to be considered. Additionally, the condyles might be adversely impacted.

- 4.

Mandibular “advancement” with a functional appliance, followed by comprehensive orthodontic treatment. This plan would require more patient cooperation, and the results would be less predictable, given the patient’s syndromic growth anomalies.

- 5.

Extract the maxillary deciduous canines and first molars, and the mandibular deciduous molars. Await the eruption of the permanent dentition and perform comprehensive orthodontic treatment to correct the Class II malocclusion. No permanent teeth would need to be extracted, but patient cooperation would be the key to success. The maxillary deciduous second molar space would require prosthetic treatment in the future.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses