The patient was an adolescent boy, aged 15.6 years, with a mutilated dentition. He had extrusion of the maxillary left first molar because of loss of the mandibular first molar and lingual tilting and rotation of the mandibular second molars. Both left and right second molars were in scissors-bite that was more severe on the left side. By using mini-implants and a TPA with hooks, a 3-mm intrusion was successfully made on the maxillary left first molar. This provided room for mesial movement of the mandibular left second molar. The second molar was protracted into the space of the missing first molar, and the mandibular left third molar was positioned in place of the second molar. The second molars scissors-bite was corrected. Active treatment took 45 months, and the treatment result remained stable 2 years after debonding.

Maxillary molar intrusion, scissors-bite correction, and mandibular molar protraction have been previously recognized as difficult. Putting an intrusive force on a tooth invariably results in an opposing reaction from the anchoring tooth. To minimize this undesirable effect, orthodontists use complex appliances that often lead to increased discomfort for patients and longer treatment times. The protraction of mandibular molars is complicated by dense cortical bone located buccally as well as wide buccolingual mandibular roots.

The introduction of skeletal anchorage with mini-implants has made it possible for orthodontists to move molars without unwanted side effects. Mini-implants offer many advantages, including a simpler, shorter, less-invasive, and more-economic procedure. This case report presents the successful treatment (with 2 years of retention) of a patient who needed maxillary molar intrusion, scissors-bite correction, and mandibular molar protraction with mini-implants for anchorage.

Diagnosis and etiology

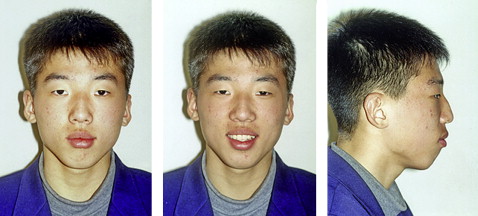

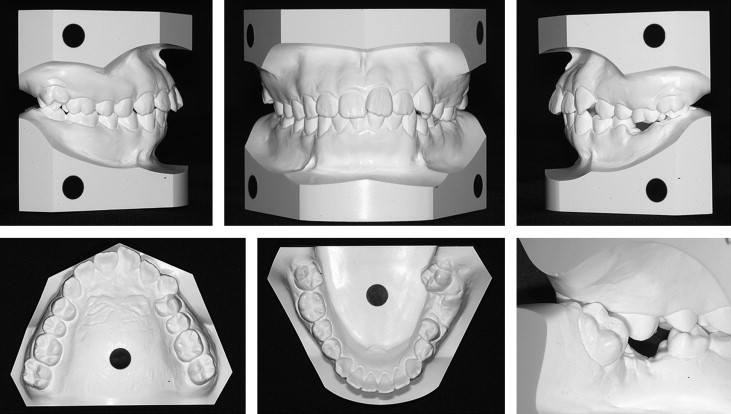

The patient, an adolescent boy aged 15.6 years, complained of a missing mandibular left first molar. Pretreatment facial photographs showed a convex profile with lip protrusion, a retrusive chin, and a relatively long lower anterior facial height ( Fig 1 ). The pretreatment intraoral photographs ( Fig 2 ) and dental casts ( Fig 3 ) demonstrated a Class I molar relationship and extrusion of the maxillary left first molar as well as lingual tilting and rotation of the mandibular second molars. Both the left and right second molars exhibited scissors-bite, with greater severity on the left side. In the maxillary arch, only minor crowding was noted, and the maxillary and mandibular midlines were coincident ( Figs 2 and 3 ). Overjet was 5.2 mm, and overbite was 2.0 mm.

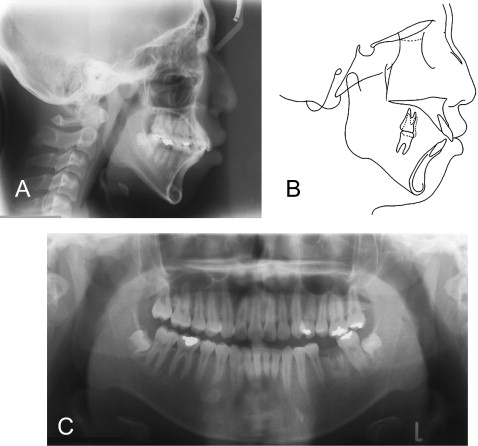

The panoramic radiograph ( Fig 4 ) showed an overerupted maxillary left first molar resulting from the missing mandibular left first molar with only root remnants remaining. The mandibular left second molar was not mesially tilted, and the third molar was present. A radiopaque mass was found below the mandibular right first premolar, but, because it had no clinical evidence of bony pathology, it was left for observation.

Cephalometric analysis ( Fig 4 , Table ) showed a Class II skeletal relationship (ANB angle, 5.8°) with a large FMA angle (34.4°) and long anterior face height (145.5 mm) suggesting a hyperdivergent pattern. The maxillary incisor inclination was in the normal range (U1 to SN, 104.2°), whereas the mandibular incisors were slightly labially inclined (IMPA, 99.2°).

| Measurement | Korean norm | T1 | T2 | T3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNA (°) | 81.8 | 75.6 | 74.9 | 75.0 |

| SNB (°) | 80.2 | 69.7 | 70.4 | 70.9 |

| ANB (°) | 1.8 | 5.8 | 4.5 | 4.1 |

| A-N perp | 1.1 | −2.1 | −2.1 | −2.3 |

| Pog-N perp | −0.3 | −19.6 | −16.9 | −15.3 |

| FHR | 66.4 | 60.2 | 62.0 | 61.7 |

| FMA (°) | 26.8 | 34.4 | 32.6 | 32.9 |

| SN-GoMe (°) | 32.0 | 47.0 | 46.0 | 45.9 |

| U1 to SN (°) | 109.0 | 104.2 | 100.0 | 99.7 |

| IMPA (°) | 90.2 | 99.2 | 86.8 | 84.1 |

| IIA (°) | 126.2 | 109.6 | 127.2 | 130.2 |

| E-UL | 1.0 | 3.1 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| E-LL | 0.3 | 7.7 | 5.5 | 4.2 |

Treatment objectives

The main treatment objectives included obtaining a functional occlusion, correcting the scissors-bite of the second molars, intruding the maxillary left first molar, and creating room for closure of the mandibular left first molar space by mesial movement of the second molar. Improvement of the protrusive facial profile was planned by using the retraction of the anterior teeth to extract the 3 first premolars and the remaining root of the mandibular left first molar. Other goals during treatment included prevention of further opening of the mandibular plane (SN-GoMe, 47.0°; FMA, 34.4°) and maintenance of the maxillary incisor inclination in the normal range after space closure.

Treatment objectives

The main treatment objectives included obtaining a functional occlusion, correcting the scissors-bite of the second molars, intruding the maxillary left first molar, and creating room for closure of the mandibular left first molar space by mesial movement of the second molar. Improvement of the protrusive facial profile was planned by using the retraction of the anterior teeth to extract the 3 first premolars and the remaining root of the mandibular left first molar. Other goals during treatment included prevention of further opening of the mandibular plane (SN-GoMe, 47.0°; FMA, 34.4°) and maintenance of the maxillary incisor inclination in the normal range after space closure.

Treatment alternatives

Two treatment options were proposed to the patient and his parents, both involving extraction of the maxillary first premolars, the mandibular right first premolar, and the remaining root of the mandibular left first molar. For the first option, protraction of the mandibular left second molar was planned with mini-implant anchorage. Despite the lengthy time for closing a mandibular first molar extraction space, the age of the patient and the cost of the implant prosthesis were factors for selection of protraction of the mandibular left second molar instead of the implant prosthesis. The shape of the mandibular left third molar appeared to make it useful as a second molar ( Fig 4 ).

An alternative treatment would reserve space for prosthetic treatment until the patient had finished growth. This space could then be treated with an implant or another restorative alternative.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses