The atrophic edentulous posterior maxilla often poses problems for implant placement. Following loss of teeth, there is a gradual loss of alveolar bone, and in many patients the sinus floor dips close to the alveolar ridge, leaving less than optimal bone height or width for placing implants. In some patients, the loss of alveolar bone coupled with increased antral pneumatization may result in only 2 to 3 mm thickness of alveolar bone height. The result is insufficient bone to place implants. It is for these patients that the sinus-lift procedures represent a treatment of choice.

Sinus-lift subantral augmentation has produced excellent results with few complications. Autogenous bone alone or in combination with particulate allografts, xenografts, or alloplasts have provided excellent results. More recently, to reduce donor site morbidity, increased blood loss, operative time, and postoperative complications allografts, xenografts, and/or alloplasts alone, or in combinations, are used as the graft of choice and without the addition of autogenous bone. The grafts are combined with the patient’s blood, platelet-rich plasma, bone marrow aspirate, aqueous antibiotics, or sterile saline. In some cases, depending on the volume of alveolar bone, simultaneous sinus-lift subantral augmentation and implant placement can be accomplished for the patient.

▪

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

As far back as the eighteenth century, successful sinus surgeries were performed using calcium sulfate as the graft material. In 1893, an American physician George Caldwell and French laryngologist Henry Luc accessed the maxillary sinus by creating a lateral window, providing access to lift the sinus membrane. Hilt Tatum in 1975 introduced a technique to increase alveolar bone height that placed graft material under the maxillary sinus membrane before placing implants. In 1980, Boyne and James, using the Caldwell-Luc procedure, grafted autogenous bone between the sinus membrane and antral floor. Smiler and Holmes reported a series of five successful subantral grafts performed via a lateral window approach using porous hydroxyapatite alone as the graft material in 1987.

▪

BIOLOGIC AND ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS

MORPHOLOGY

The adult maxillary sinus, antrum of Highmore, lies within the body of the maxilla. It is the largest paranasal sinus, measuring on average 34 mm × 33 mm × 23 mm with a 15 mL volume. It can occupy the body of the maxilla from the tuberosity to the canine fossa. The root apices of molar teeth can extend into the sinus, with only a thin sheet of bone or connective tissue separating the antrum from the oral cavity. With age and loss of maxillary posterior teeth, there is progressive alveolar atrophy, increased pneumatization of the sinus, and thinning of the buccal wall.

The maxillary sinus is shaped as a quadrangular pyramid. The sides are directed superiorly, inferiorly, posteriorly, and anteriorly. The apex of the pyramid is pointed laterally into the zygomatic process. The base is directed medially toward the lateral wall of the nose. The medial wall of the sinus is the most complex. It contains the nasolacrimal duct, which lies on average 4 to 9 mm anterior to the maxillary ostium. This duct drains tears and runs from the lacrimal fossa in the orbit, down the posterior aspect of the maxillary vertical buttress, and empties into the anterior aspect of the inferior meatus.

The ostium of the maxillary antrum is located in the superior aspect of the medial wall of the sinus and empties mucus into the posterior aspect of the hiatus semilunaris. The anterior wall contains the infraorbital foramen with the infraorbital nerve running over the roof of the sinus and exiting through the foramen. The thinnest portion of the anterior wall is just above the canine fossa. The posterior wall is located behind the pterygomaxillary fossa and is pierced by the posterior superior alveolar nerves and lies in close proximity to the internal maxillary artery, the sphenopalatine ganglion, the foramen rotundum, and the greater palatine nerve.

The superior wall of the maxillary sinus is the floor of the orbit, through which runs the infraorbital canal and nerve. The floor of the sinus is approximately 1.00 to 1.25 cm below the level of the nasal cavity.

The mucosal lining of the sinus has a rich vascular network of complex vascular loops that help warm and filter inspired air. Pseudostratified columnar ciliated epithelium and connective tissue line the maxillary sinus. The rapid, rhythmic sweeping movements of the cilia remove the mucus that goblet cells secrete, with the debris and bacterial contaminants, toward the ostium to the middle meatus of the nose.

▪

BIOLOGIC AND ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS

MORPHOLOGY

The adult maxillary sinus, antrum of Highmore, lies within the body of the maxilla. It is the largest paranasal sinus, measuring on average 34 mm × 33 mm × 23 mm with a 15 mL volume. It can occupy the body of the maxilla from the tuberosity to the canine fossa. The root apices of molar teeth can extend into the sinus, with only a thin sheet of bone or connective tissue separating the antrum from the oral cavity. With age and loss of maxillary posterior teeth, there is progressive alveolar atrophy, increased pneumatization of the sinus, and thinning of the buccal wall.

The maxillary sinus is shaped as a quadrangular pyramid. The sides are directed superiorly, inferiorly, posteriorly, and anteriorly. The apex of the pyramid is pointed laterally into the zygomatic process. The base is directed medially toward the lateral wall of the nose. The medial wall of the sinus is the most complex. It contains the nasolacrimal duct, which lies on average 4 to 9 mm anterior to the maxillary ostium. This duct drains tears and runs from the lacrimal fossa in the orbit, down the posterior aspect of the maxillary vertical buttress, and empties into the anterior aspect of the inferior meatus.

The ostium of the maxillary antrum is located in the superior aspect of the medial wall of the sinus and empties mucus into the posterior aspect of the hiatus semilunaris. The anterior wall contains the infraorbital foramen with the infraorbital nerve running over the roof of the sinus and exiting through the foramen. The thinnest portion of the anterior wall is just above the canine fossa. The posterior wall is located behind the pterygomaxillary fossa and is pierced by the posterior superior alveolar nerves and lies in close proximity to the internal maxillary artery, the sphenopalatine ganglion, the foramen rotundum, and the greater palatine nerve.

The superior wall of the maxillary sinus is the floor of the orbit, through which runs the infraorbital canal and nerve. The floor of the sinus is approximately 1.00 to 1.25 cm below the level of the nasal cavity.

The mucosal lining of the sinus has a rich vascular network of complex vascular loops that help warm and filter inspired air. Pseudostratified columnar ciliated epithelium and connective tissue line the maxillary sinus. The rapid, rhythmic sweeping movements of the cilia remove the mucus that goblet cells secrete, with the debris and bacterial contaminants, toward the ostium to the middle meatus of the nose.

▪

VASCULAR SUPPLY—LYMPHATIC DRAINAGE AND INNERVATIONS

ARTERIAL SUPPLY

Branches of the maxillary artery, via the external carotid artery, supply the maxillary sinus. These include: the infraorbital artery as it runs with the infraorbital nerve, the terminal branches of the sphenopalatine artery, and the posterior lateral nasal artery that supplies the medial wall of the maxillary sinus and the mucous membrane lining of the lateral nasal wall. Branches of the facial artery and from the pterygopalatine artery, the greater palatine artery, the alveolar artery, and the posterior superior alveolar artery supply the lateral wall of the sinus.

VENOUS RETURN AND LYMPHATIC DRAINAGE

Venous return of the anterior region of the maxillary sinus drains from the cavernous plexus into the facial vein. The posterior return is into the pterygoid plexus of veins via the sphenopalatine vein and the retromandibular and facial veins. These empty into the internal jugular vein. The lymphatic drainage from the maxillary sinus is via the infraorbital foramen through the ostium and into the submandibular lymphatic system.

NERVE INNERVATION

The maxillary branch of the trigeminal nerve and its subdivisions innervate the maxillary sinus. The infraorbital subdivision divides into three branches before exiting the infraorbital foramen. The posterior superior alveolar, middle superior alveolar, and the anterior superior alveolar nerve subdivisions innervate the maxillary sinus, the maxillary teeth, and the buccal surfaces of the gingiva. The anterior superior alveolar nerve, off the infraorbital nerve, lies within the infraorbital canal, situated in the anterior wall of the maxillary sinus. The middle superior alveolar nerve travels first in the roof of the maxillary sinus and then converges with the posterior superior alveolar nerve. Both the anterior superior alveolar nerve and middle superior alveolar nerve also innervate the mucosa of the inferior meatus and floor of the nasal cavity.

▪

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

To ensure antibiotic coverage before the incision, surgical antibiotic prophylaxis of either penicillin (amoxicillin 2000 mg, or Augmentin 2000 mg) or clindamycin 600 mg is taken orally 2 hours before the procedure. Before the patient is seated for surgery, the teeth are brushed and the mouth rinsed with chlorhexidine solution. The oral and perioral regions are then prepared and draped for a sterile surgery procedure.

▪

ANESTHESIA

The sinus-lift subantral augmentation surgery and all of its variations can be performed with local anesthesia with 1 : 200,000 epinephrine. The posterior superior alveolar nerve block combined with the anterior superior alveolar nerve block and palatal infiltration with local anesthesia is usually sufficient to obtain complete anesthesia. Another option is injection of the greater palatine foramen. Local anesthesia can be combined with oral sedation, intravenous sedation, or general anesthesia.

▪

INCISION

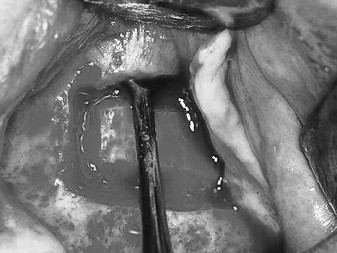

A crestal incision is made along the alveolar crest from the tuberosity to the anterior border of the sinus. A vertical relaxing incision, anterior to the planned osteotomy, is made to the depth of the vestibule to facilitate tissue release. Dissection is initiated at the apex of the crestal and vertical relaxing incisions. The mucoperiosteal flap is reflected with a periosteal elevator or molt curette to expose the canine fossa, malar buttress, and the infratemporal fossa ( Figure 26-1 ). Care is taken not to tear the periosteum.

▪

QUADRILATERAL BUCCAL OSTEOTOMY

Although the hinge osteotomy was one of the first approaches for sinus-lift grafting, this procedure only worked well when there was sufficient vertical maxillary bone height. The quadrilateral buccal osteotomy is indicated for either normal or minimal vertical maxillary bone height. An advantage of quadrilateral osteotomy is that it permits the sinus membrane to be elevated higher than the superior horizontal osteotomy. The surgery proceeds after reflection of the mucoperiosteal flap and exposure of the lateral wall of the maxilla, the canine fossa, the malar buttress, and infratemporal fossa. An inferior horizontal osteotomy begins 2 to 3 mm above the floor of the antrum in the area of the first molar, using a #6 or #8 round bur and copious irrigation ( Figure 26-2 ). A small round bur or a fissure bur must not be used because this will most likely cause tearing of the schneiderian membrane.

The osteotomy is done with a light touch, stripping away bone until the membrane is exposed. The anterior limit of the osteotomy is the anterior limit of the sinus. If bicuspid teeth are present, the anterior limit is 3 to 4 mm distal to the tooth. The osteotomy extends to the region of the second molar as the posterior limit of the bone cut.

The anterior vertical bone cut is begun from the inferior horizontal osteotomy and extended as high as access permits. The superior horizontal osteotomy extends from the superior limit of the anterior vertical bone cut posterior to approximate the length of the inferior horizontal osteotomy. A posterior vertical osteotomy connects the inferior and superior horizontal bone cuts to complete the quadrilateral osteotomy ( Figure 26-3 ).

▪

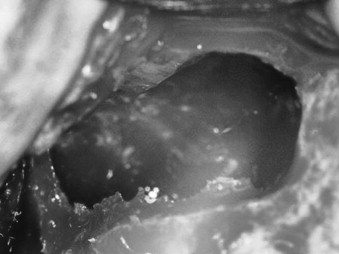

ELEVATION OF THE SCHNEIDERIAN MEMBRANE

The quadrilateral osteotomy exposes the schneiderian membrane circumferentially around the bone cuts. The membrane is first lifted along the superior horizontal osteotomy using broad-based freer elevators or curettes ( Figure 26-4 ). The membrane can be elevated higher than the superior bone cut ( Figure 26-5 ). This is especially important when the anatomy and resorption patterns restrict visibility and exposure.

With the sharp border of the dissection elevators placed on bone and its broad base supporting the membrane, the membrane is lifted from its anterior and posterior walls ( Figure 26-6 ). Further dissection exposes the medial wall of the sinus ( Figure 26-7 ). The buccal osseous window stays attached to the schneiderian membrane as elevation continues. The bony wall turns inward and is positioned horizontally in the superior aspect of the dissection.

Piezosurgery with the diamond-coated insert or saw insert will cut a precision osteotomy ( Figure 26-8 ). The quadrilateral osteotomy ( Figure 26-9 ) can be removed, exposing the sinus membrane ( Figure 26-10 ). Using the noncutting, smooth insert, the membrane is elevated ( Figure 26-11 ). The elevated membrane exposes the medial, inferior, and posterior bone walls of the sinus ( Figure 26-12 ).

▪

GRAFTING THE OSSEOUS CAVITY

Graft material is placed under the membrane within the osseous cavity in an anterior inferior direction and with a loose compaction. It is important that the graft is in contact with the medial osseous wall ( Figure 26-13 ). Graft is added until the cavity is loosely filled, reconstituting the buccal wall ( Figure 26-14 ). Overpacking the site and/or pressure in a superior direction is avoided because this might tear the membrane. Also, overcompressing the graft restricts blood flow into the material, inhibits angiogenesis, and decreases oxygen tension and compromises success. The mucoperiosteal flap is then repositioned and sutured. If the periosteum is torn, a hemostatic collagen wound dressing or a guided bone regeneration (GBR) membrane can be placed over the buccal window to inhibit fibrovascular into the graft ( Figure 26-15 ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses