This article discusses imaging techniques for visualization of the temporomandibular joint. Conventional plain film modalities are discussed briefly, with an emphasis on the more contemporary modalities, such as CT with cone-beam technology, MRI, and nuclear imaging, including single-photon emission computed tomography, and positron emission tomography. Indications, advantages, and limitations are discussed. As advancements in this area continue, our understanding of this complex joint and its pathology will follow, which will lead to more defined imaging indications and ultimately, to improved treatment outcomes.

Imaging modalities of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) have continued to evolve during the past decade. With the advent of newer techniques and computer enhancements, TMJ imaging has enabled a better appreciation for TMJ anatomy and function. Correlation of these images with clinical findings has led to an improved understanding of the pathophysiology of TMJ disorders. As our understanding of TMJ disorders progresses, the development of new treatment algorithms will ensue. Current management of TMJ disorders relies heavily on clinical evaluation, with minor influence from information obtained through TMJ imaging. Although TMJ imaging in a clinical setting may have declined, it still has an expanding role at the research level in the quest for greater understanding of this complex group of joint disorders .

The goals for TMJ imaging include evaluating the integrity of the structures when disease is suspected, determining the extent of disease or monitoring its progression when disease is present, and evaluating the effects of treatment. Specific anatomic areas of the TMJ include the mandibular condyle, the glenoid fossa, the articular eminences of the temporal bone, and the soft tissue components of the articular disk, its attachments, and the joint cavity.

As with any laboratory test or imaging, clear indications should be established to justify the test. The need for TMJ imaging should be determined at an individual level after taking a thorough history and performing an appropriate clinical examination of the patient. The symptoms and signs presented should guide a practitioner to develop a differential diagnosis of possible TMJ pathology. Based on the differential diagnosis, the most appropriate mode of imaging should then be ordered, with consideration given to how the image results will influence overall management. Other factors that should be considered when determining the appropriate mode of imaging include the likelihood of hard or soft tissue pathology, the availability of specialized equipment, the cost of the examination, the amount of radiation exposure, and any contraindications, such as allergy to intravenous contrast agents or pregnancy. The efficacy of the technique will be determined by the quality of the image obtained combined with the skills of the person interpreting the image.

This article reviews the various techniques available for imaging the TMJ, with emphasis on contemporary imaging modalities, and includes a discussion of the method, indications, advantages, and limitations. The following techniques are included: plain film radiography, tomography, panoramic radiology, arthrography, ultrasonography, CT, MRI, and nuclear imaging.

Plain film radiography

Plain films refer to X rays made with a stationary x-ray source and film. Plain films of the TMJ depict only mineralized parts of the joint, such as bone; they do not give any information about nonmineralized cartilage, soft tissues, or the presence of joint effusion. Radiographic changes are often not seen until a sufficient volume of destruction or alteration in bone mineral content has occurred . Plain films are also limited by the superimposition of adjacent structures, which can make visualizing all parts of the joint difficult. To overcome this limitation, multiple plain film techniques have been developed to image the joint from various angles. Plain films are the least expensive and require simple equipment that is often available in the dental office. Although many of these techniques have been superseded by CT, which offers superior anatomic visualization of joint structures, several plain film views have traditionally been used to image the TMJ and have contributed to our diagnosis and treatment of TMJ disorders.

Transcranial view

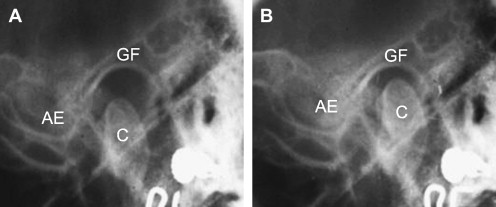

The introduction of the transcranial view of the TMJ is attributed to Schuller in 1905. In this lateral oblique transcranial projection, the x-ray beam is directed parallel to the long axis of the condyle. At this angulation, the cranial bones are the only structures superimposed over the joint. As a result, a sharp image of the mandibular condyle, articular eminence, and glenoid fossa is obtained ( Fig. 1 ). The transcranial view shows mainly the lateral part of the joint and can be used to determine condylar position and size, depth of the fossa, slope of the eminence, and width of the joint space.

Transmaxillary view

In the transmaxillary view technique, the x-ray beam is directed perpendicular to the long axis of the condyle. Changing the vertical and horizontal orientation helps with condyle and mastoid process superimposition. The lower jaw is also protruded to avoid superimposition of the condyle onto the base of the skull. This view, along with the transcranial view, provides a three-dimensional evaluation of the condyle for fractures, severe degenerative joint disease, and neoplasms.

Submentovertex view

The submentovertex view directs the x-ray beam through the chin region parallel to the posterior border of the ramus toward the base of the skull. This view shows the angulations of the long axes of the condyles relative to a line drawn between the auditory canals and the cephalostat ear rods (if used to position the patient), or to a perpendicular midsagittal line. This view is a useful supplement to examine condylar displacement and rotation in the horizontal plane associated with trauma or facial asymmetry. Because the patient is positioned with full neck extension, this technique is contraindicated in trauma patients who are suspected of neck injury.

Other views

The transpharyngeal view involves placing the x-ray tube close to the contralateral joint and aiming the beam toward the opposite joint, which is adjacent to the film. As a result, the joint nearer the film is in focus, whereas the joint closest to the x-ray source appears out of focus. This projection provides an acceptable view of the TMJ, condylar neck, mandibular ramus, and zygomatic region.

The Reverse Towne’s projection positions the patient’s forehead directly against the film. The patient is then instructed to open his/her mouth to bring the condylar head out of the glenoid fossa, thus reducing the superimposition of these structures on one another. The x-ray beam is then positioned behind the patient’s occiput at a 30° angle to the horizontal and centered on the condyles. This projection offers an excellent view of the condylar neck and is useful in the trauma setting when a condylar fracture is suspected .

Posterior-anterior and lateral cephalograms give little information about the TMJ itself because of the superimposition of adjacent bony structures. However, they can be used for serial examinations of patients who have skeletal asymmetry.

With the increasing use and availability of CT and cone-beam CT, the use of plain films for imaging the hard tissues of the TMJ is becoming less popular.

Conventional tomography

Tomography is a radiographic technique that clearly depicts a specific slice or section of the patient. Understanding the concept of sectional images is important because it has become the basis for many modern imaging techniques we use today, such as panoramic radiography and CT. In conventional tomography, the x-ray source and film simultaneously move around a fixed rotation point in opposite directions. Objects lying within a specific plane of interest are seen in focus, whereas those structures outside the predetermined focal plane appear blurred. Varying patterns of tomographic movement, or rotation, can be performed to ensure the clearest view of the bony components of the TMJ and to reduce the problem of superimposition. The disadvantages of tomography include the inability to evaluate soft tissue and the fact that the required equipment is more expensive than a conventional x-ray machine. With the advent of CT and MRI, which have superior low-contrast resolution, conventional film tomography is used less frequently.

Conventional tomography

Tomography is a radiographic technique that clearly depicts a specific slice or section of the patient. Understanding the concept of sectional images is important because it has become the basis for many modern imaging techniques we use today, such as panoramic radiography and CT. In conventional tomography, the x-ray source and film simultaneously move around a fixed rotation point in opposite directions. Objects lying within a specific plane of interest are seen in focus, whereas those structures outside the predetermined focal plane appear blurred. Varying patterns of tomographic movement, or rotation, can be performed to ensure the clearest view of the bony components of the TMJ and to reduce the problem of superimposition. The disadvantages of tomography include the inability to evaluate soft tissue and the fact that the required equipment is more expensive than a conventional x-ray machine. With the advent of CT and MRI, which have superior low-contrast resolution, conventional film tomography is used less frequently.

Panoramic radiography

This imaging technique is one of the most commonly used by dentists and dental specialists. The fundamental principle behind panoramic radiography is based on the tomographic concept of imaging a section of the body while blurring images outside the desired plane. The x-ray source and film are set opposite to each other and rotate around the whole head with a narrow focal trough so that the TMJs and teeth are in focus, but the adjacent structures are blurred. The narrow focal trough is produced by lead collimators in the shape of a slit located at the x-ray source and the film. The size and shape of the focal trough and the number of rotation centers vary with the manufacturer of the panoramic unit.

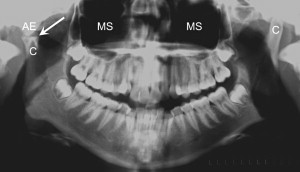

Panoramic radiography is a useful screening technique for condylar abnormalities such as erosions, sclerosis, osteophyte formation, resorption, and fractures ( Fig. 2 ). In addition, the panoramic film also gives information about the teeth, mandible, and maxilla, which may help with the overall diagnosis by ruling out odontogenic sources or other pathology of the jaws. However, a disadvantage of panoramic radiography is that the glenoid fossa and articular eminences are not well visualized because of the superimposition of the base of the skull and zygomatic arches. Condylar position also cannot be evaluated because the mouth is slightly open and protruded during this view .

Arthrography

Arthrography is an imaging method by which radiopaque contrast dye is injected into the lower TMJ spaces under fluoroscopic guidance to image the soft tissue structures. Katzberg and colleagues introduced this modified arthrotomographic technique for TMJ imaging in 1979. Before this, plain films and conventional tomography were the only methods available for imaging the TMJ. In contrast to the previous imaging techniques, which were static views of the joint, arthrography was the first dynamic study of the joint . According to the pattern by which the contrast agent flows, adhesions, disk perforations, and disk function can be studied during open and closing movements. This technique is ideal for small disk perforations and for visualizing the movement of the joints.

The disadvantages of arthrography are that it is an invasive procedure, requiring insertion of a needle into the TMJ by a skilled operator, which may result in complications, such as bleeding and introduction of infection. Another disadvantage is the potential for an allergic reaction to the contrast agent and the high radiation exposure. The fact that a needle is inserted into the joint under anesthesia does, however, afford the operator the opportunity to perform a simultaneous arthrocentesis so that the procedure can be diagnostic and therapeutic. Arthrography is rarely used today because of its invasiveness and the associated radiation exposure to the patient. Other imaging modalities such as MRI now offer excellent soft tissue depiction without the need for injection of contrast or radiation exposure .

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography uses sound waves of high frequency to produce images of the body. As the sound waves travel through the body, they encounter a boundary between tissues of varying densities. Depending on the density, or resistance, of the tissue, reflective echoes are returned to the ultrasound probe at different speeds and relayed to a machine that translates the echoes into a picture.

Ultrasonography has been described in imaging the TMJ with some beneficial, albeit limited, results . Most favorable results have been noted in relation to evaluating disk position, with minimal benefit in evaluating hard tissue changes . Gateno and colleagues used ultrasonography for intraoperative assessment of condylar position in relation to the glenoid fossa during mandibular ramus osteotomy procedures. Condylar position was identified correctly in 38 of 40 ultrasound images with a sensitivity of 95% . However, later studies using ultrasonography to evaluate condylar erosion and osteoarthritic changes of the condyle found it to be inferior to CT imaging, mainly because of interference by reflective echoes from the glenoid fossa .

When evaluating TMJ disk position for internal derangement, ultrasonography has shown some benefit, especially when high-resolution, dynamic, real-time ultrasonography is used . However, ultrasonographic evaluation of the TMJ disk position is currently associated with a high number of false-positives, which could ultimately result in overtreatment. Currently, MRI is more accurate and continues to be the gold standard for imaging soft tissue of the TMJ .

As advancements in ultrasound probe technology continue, more detailed imaging and improvement in tissue differentiation may contribute to a reduction in the number of false-positives and, therefore, overtreatment. Further research in this imaging modality for the TMJ is needed because ultrasonography offers many advantages, including reduced cost, accessibility, fast results, decreased examination time, and lack of radiation exposure.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses