Clinical orthodontics is a service that should be grounded in science and biology. The science of decision in treatment planning implies identification of alternative procedures, prediction of the relative odds in favor of the desired long-term outcome for each option, and evaluation of the relative cost-risk-benefit ratios of each alternative. The decision should be comprehensible to the patient or parents and best meet the patient’s needs. Whether canine substitution, single implants, or tooth-supported restorations is the method of choice for patients with missing maxillary lateral incisors, many challenges are involved in obtaining and retaining an optimal result.

Rationale for space closure

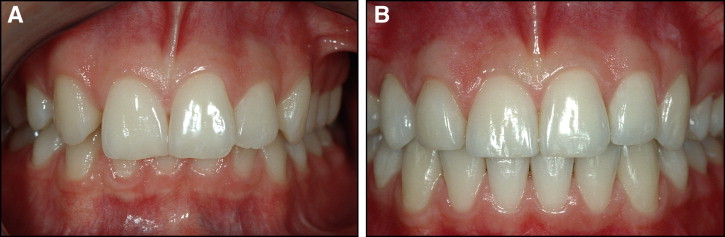

Maxillary lateral agenesis is generally diagnosed in children at a young age. Therefore, the most important treatment decisions must be linked to the long-term outcome, since change over time is normal in biologic systems. The treatment result should preferably be completed when the patients are in their young teens and should be expected to reflect a natural dentition over a long life, which might span 60 or more years. Conventional space closure for missing maxillary lateral incisors is a viable and safe procedure that provides satisfactory esthetic and functional long-term results. Further improvements by orthodontists in tooth reshaping and positioning and progress in restorative treatment with individual tooth bleaching, thin porcelain veneers, and hybrid composite resin buildups demonstrate that quality treatment can be obtained when space closure is combined with esthetic dentistry. Close teamwork with a skilled prosthodontist is fundamentally important for the final outcome. Such results can be almost indistinguishable from natural dentitions ( Figs 1 , B , and 2 , B ) and are likely to remain so in a life-long perspective. Properly made ultrathin-thin enamel-bonded ceramic veneers have proved to be esthetic and extremely durable restorations.

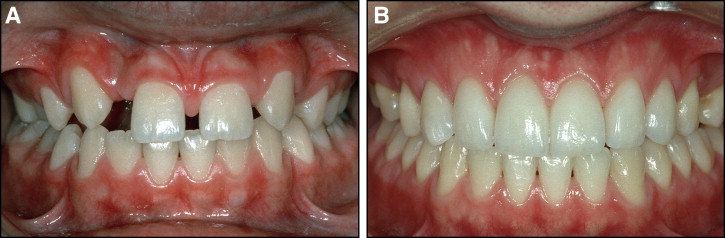

In comparison, although high survival rates for implants and implant-supported crowns can be expected, biologic and technical complications are frequent, and may appear even after only a few years. A major problem with implants is that at present it is not possible to predict either when, to what degree, or in which patients unesthetic soft- and hard-tissue changes around implant-supported porcelain crowns in the anterior maxilla will occur. For this reason, it is our opinion that, if the treatment plan in young patients must include space opening, it might be preferable to open the spaces posteriorly and place implants in the premolar areas ( Fig 2 ). For adults, decisions on whether to use space closure or implants should be discussed in interdisciplinary cooperation. Frustrating practical problems can arise when the orthodontic treatment is finished in adolescents and a waiting period of 5 or more years is needed before placing the implant. Temporary restorations with resin-bonded fixed partial dentures (FPDs) or a removable plate with plastic teeth is rarely appreciated, and adjacent roots might move so much in the interim period that orthodontic retreatment is necessary. This is illustrated in Figure 2 , B .

Restorative procedures other than implants, including resin-bonded FPDs, cantilevered FPDs, and conventional full-coverage FPDs can be used with success in favorable situations, although debonding over time might be a common cause of failure. New developments with bondable translucent ceramics with adequate strength have shown promising results when a cantilevered lateral pontic is bonded to a canine.

No evidence for establishment of Class I canine relationship

Long-term periodontal and occlusal studies have shown that space closure can lead to an acceptable functional relationship, with a modified group function on the working side. Nordquist and McNeill reexamined 33 treated patients with at least 1 missing maxillary lateral incisor (39 with space closure, and 19 with space reopening and FPDs). The mean postorthodontic treatment interval was 9 years 8 months, with a range of 2.3 to 25.6 years. They found (1) that patients with lateral incisor spaces closed were significantly healthier periodontally than those with prosthetic lateral incisors, (2) no difference in adequacy of occlusal function between the 2 groups, and (3) no evidence to support that establishing a Class I canine relationship should be the preferred mode of treatment.

The major advantages of orthodontic space closure for young patients with lateral incisor agenesis and a coexisting malocclusion are the permanence of the finished result and the possibility to complete treatment in early adolescence.

More recently, Robertsson and Mohlin reevaluated 50 treated patients with lateral incisor agenesis (mean age, 26 years; range, 18-55 years). The mean time after treatment was 7.1 years (range, 0.5-13.9 years). Thirty patients had received space closure, and 20 had space opening with fixed restorative options, but not implants. They found that (1) the space-closure patients were more satisfied with the treatment results than the prosthesis patients, (2) there was no difference between the 2 groups in prevalence of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular joint dysfunction, and (3) patients with prosthetic replacements had impaired periodontal health with accumulation of plaque and gingivitis. It was concluded that orthodontic space closure produces results that are well accepted by patients, does not impair temporomandibular joint function, and encourages periodontal health in comparison with the prosthetic replacements.

No evidence for establishment of Class I canine relationship

Long-term periodontal and occlusal studies have shown that space closure can lead to an acceptable functional relationship, with a modified group function on the working side. Nordquist and McNeill reexamined 33 treated patients with at least 1 missing maxillary lateral incisor (39 with space closure, and 19 with space reopening and FPDs). The mean postorthodontic treatment interval was 9 years 8 months, with a range of 2.3 to 25.6 years. They found (1) that patients with lateral incisor spaces closed were significantly healthier periodontally than those with prosthetic lateral incisors, (2) no difference in adequacy of occlusal function between the 2 groups, and (3) no evidence to support that establishing a Class I canine relationship should be the preferred mode of treatment.

The major advantages of orthodontic space closure for young patients with lateral incisor agenesis and a coexisting malocclusion are the permanence of the finished result and the possibility to complete treatment in early adolescence.

More recently, Robertsson and Mohlin reevaluated 50 treated patients with lateral incisor agenesis (mean age, 26 years; range, 18-55 years). The mean time after treatment was 7.1 years (range, 0.5-13.9 years). Thirty patients had received space closure, and 20 had space opening with fixed restorative options, but not implants. They found that (1) the space-closure patients were more satisfied with the treatment results than the prosthesis patients, (2) there was no difference between the 2 groups in prevalence of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular joint dysfunction, and (3) patients with prosthetic replacements had impaired periodontal health with accumulation of plaque and gingivitis. It was concluded that orthodontic space closure produces results that are well accepted by patients, does not impair temporomandibular joint function, and encourages periodontal health in comparison with the prosthetic replacements.

Common esthetic problems with orthodontic space closure

Some common objections to orthodontic space closure are that the treatment result might not look “natural,” the functional occlusion is compromised, and the retention of the treatment result is difficult. Particularly in patients with unilateral agenesis, space closure can create a problem in matching size, shape, and color. This is because the canine normally is longer and larger (mesiodistally and labiolingually) than the lateral incisor it will replace ( Fig 1 , A ), and more saturated with color. The first premolar is generally shorter and narrower than the contralateral canine ( Fig 1 , A ). If these differences are not compensated for, the esthetic outcome will be compromised. It seems to be common among orthodontists not to fully address the natural size difference between a first premolar and a canine, so that the premolars substituting for canines are too diminutive.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses