10 Congenital and Developmental Abnormalities

Salivary Gland Aplasia and Duct Abnormalities

First Branchial Cleft Anomalies

Pediatric Salivary Gland Surgery

Introduction

Swelling in the region of the salivary gland in children is not uncommon. The swellings are usually inflammatory lesions, and true neoplasms are rare. This chapter discusses congenital and developmental abnormalities that arise in the salivary glands. These are more commonly related to the vascular structures in the salivary glands or to branchial remnants than to the salivary tissue itself.

Epidemiology

True salivary gland aplasia is very rare and limited to a small number of case reports in the literature.1 However, vascular anomalies affecting the salivary gland are relatively common. Ten per cent of Caucasian infants are affected by hemangiomas,2 a small proportion of which are within the salivary glands, particularly the parotid gland. Lymphatic malformations are thought to affect one in 3500 infants and are mainly found in the head and neck and limbs.

The most frequent congenital salivary gland tumor is a hemangioma.

The most frequent congenital salivary gland tumor is a hemangioma.

Diagnostic Work-Up

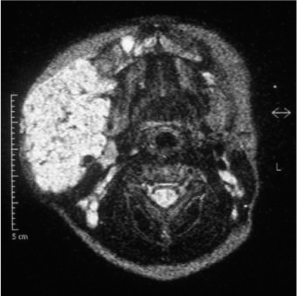

The diagnosis of vascular anomalies is predominantly clinical, supported by imaging, but tissue biopsy may be required in cases of uncertainty. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can provide detailed anatomic information about vascular anomalies (Fig. 10.1) and is complemented by Doppler ultrasound, which can provide information about flow. Rapid growth of hemangiomas may cause concern about a possible underlying malignancy.

Fig. 10.1 An axial MR image, showing a large hemangioma infiltrating the right face.

Imaging of the vessels using MRI and Doppler ultrasound is essential in vascular anomalies of the salivary gland.

Imaging of the vessels using MRI and Doppler ultrasound is essential in vascular anomalies of the salivary gland.

Salivary Gland Aplasia and Duct Abnormalities

There have been rare reports of salivary gland aplasia,1,3 which may be associated with lacrimal gland aplasia4 or ectodermal dysplasia.5 Occasional ectopia or duplication abnormality of the ducts occurs, with an external opening.6

Congenital Vascular Anomalies

The main congenital abnormalities of the salivary glands are due to vascular anomalies. For many years, the classification of congenital vascular anomalies was complicated and confused. This is no longer the case. A new classification was proposed in 1982, based on the biologic nature of the anomaly.7 Two main categories emerged from this study:

Hemangiomas are vascular tumors that grow by cellular (mainly endothelial) hyperplasia. They have a characteristic growth pattern. The very common infantile hemangioma will involute during the early years of life.

Hemangiomas are vascular tumors that grow by cellular (mainly endothelial) hyperplasia. They have a characteristic growth pattern. The very common infantile hemangioma will involute during the early years of life.

Vascular malformations, by contrast, have a quiescent epithelium and grow at a rate commensurate with other tissues. They have been subdivided according to the predominant vessel type.

Vascular malformations, by contrast, have a quiescent epithelium and grow at a rate commensurate with other tissues. They have been subdivided according to the predominant vessel type.

Lymphatic and venous malformations are the main intraparotid lesions.

Lymphatic and venous malformations are the main intraparotid lesions.

Salivary Gland Hemangiomas

Salivary Gland Hemangiomas

Salivary gland hemangiomas are most commonly found in the parotid gland in infants and young children.8

Clinical Features and Diagnostic Work-Up

There is usually minimal swelling at birth. Over the first 6–8 weeks of life, there is rapid proliferation and a mass appears. There may be redness of the overlying skin, but in deep lesions the skin color is normal. The characteristic redness of the skin helps with the diagnosis of superficial lesions, but deep lesions may be more difficult to diagnose. The rapid growth in this situation may raise concerns about a possible underlying malignancy.

The diagnosis is clinical, supported by ultrasound imaging or magnetic resonance scanning. On rare occasions, a biopsy is needed. The majority of lesions are treated conservatively and simply regress spontaneously over the first 2–4 years of life.

Treatment

Medical treatment is indicated in some cases to try and control the growth of very large lesions. Corticosteroid treatment has been the mainstay of treatment for many years. Typical regimens would involve prednisolone up to 2 mg/kg for several months. However, long-term treatment has many side effects, including hypertension, weight gain, hyperglycemia, and osteoporosis. Interferon-α has also been used, but is also limited by side effects, particularly spastic diplegia.9

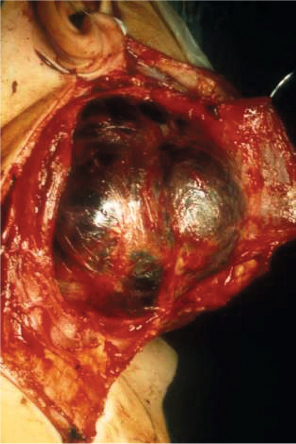

There has been considerable interest recently in treating hemangiomas with propranolol, since a chance discovery in France in 2008.10 Dramatic shrinkage can be obtained with this medication.11 The safe dose and clinical indications for propranolol have not yet been fully evaluated. The duration of treatment is based on the clinical response, but some lesions have started to grow again once propranolol has been discontinued. The mechanism is poorly understood, but propranolol is increasingly being used to control the growth of extensive lesions. Long-term treatment for a year or more may be required and great caution should be used, as side effects including hypotension and bradyarrhythmias can result. Cardiac failure is not uncommon in children with extensive hemangiomas, and propranolol can exacerbate this. Children should have a careful cardiovascular assessment before propranolol treatment is commenced. It is also becoming clear that certain types of hemangioma respond poorly to propranolol. Surgery may be indicated in these cases (Figs. 10.2 and 10.3). The place of propranolol in the treatment of smaller lesions is unclear.

Fig. 10.2 a, b Preoperative view of a patient with a large hemangioma in the submandibular region. The tumor was resected via a combined submandibular and transoral approach after failure of conservative treatment.

Fig. 10.3 The intraoperative site following a classic preauricular–submandibular skin incision for the parotid approach, with exposure of a large hemangioma.

Fig. 10.4 Lymphangioma of the left hemiface, with a large mass in the lower parotid region and submandibular area, here reaching the contralateral side. Typically, the tongue is pushed up by the submandibular mass.

The majority of hemangiomas regress spontaneously with the first 2–4 years of life. Only a minority of patients need more aggressive treatment.

The majority of hemangiomas regress spontaneously with the first 2–4 years of life. Only a minority of patients need more aggressive treatment.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses