Patient diagnosis

Diagnoses and problems

Armed with the significant findings from the examination process, the dentist now begins to assemble a list of diagnoses for the patient. Diagnoses are precise, scientific terms used to describe variations from normal. They can be applied to a systemic disease, such as diabetes, or a specific oral health condition, such as aggressive periodontitis. Other examples of diagnoses include occlusal caries, irreversible pulpitis, squamous cell carcinoma (SCCA), and Class II malocclusion. Often, more than one finding may be necessary to formulate a diagnosis. For example, a tooth that appears darker than the others may or may not be a significant finding. This finding, concurrent with a tooth that tests negative to electric pulp testing and the radiographic appearance of a periapical radiolucency, would strongly suggest pulpal necrosis.

![]() Images in the tables can be viewed larger in the expanded chapter on Evolve.

Images in the tables can be viewed larger in the expanded chapter on Evolve.

Several types of diagnoses are possible. When several findings point clearly to a specific disease entity, the clinician may make a definitive diagnosis, indicating a high level of certainty. On the other hand, when the findings suggest several possible conditions, the process of distinguishing among the list of possibilities is referred to as a differential diagnosis. For example, the differential diagnosis of a lump on the patient’s palate might require differentiation among such possibilities as a maxillary torus, a salivary gland tumor, or an odontogenic infection. Without more information, such as findings from a radiograph or a biopsy result, it may be impossible to reach a definitive diagnosis. A “golden rule” of treatment planning is that a diagnosis should be made before treatment begins. When the diagnosis is uncertain, but it is prudent to begin some type of treatment, a working or tentative diagnosis may be made. Diagnostic tests, consultation with other providers, or reevaluation of the patient will usually be required to either confirm the diagnosis or to change to a new, more definitive, diagnosis.

On many occasions, a precise diagnosis that matches a significant finding may not be achievable. For example, the patient may reveal that he or she has limited funds available for dental treatment. This is a significant finding that may affect the treatment plan but it does not fit the classic definition of a diagnosis. Such issues are typically referred to as problems. Patient problems can be general or specific issues that suggest the need for attention. Common examples of patient problems include dental pain of undetermined origin, fear of dental treatment, or the patient who requires the assistance of a caregiver to brush the teeth.

Benefits of a diagnosis and problem list

After completing the patient examination, the dentist must assemble and organize all the significant findings to create a list of patient diagnoses and problems. This list is then documented in the patient record. The benefits of creating such a list include:

Foundation for the treatment plan

When generating a patient’s treatment plan or plan of care each treatment on the plan must be justified by one or more diagnoses or reasons for treatment . The patient’s diagnosis is the essential basis for any treatment plan. A treatment plan that lacks this foundation is often missing key components. Important patient concerns and/or oral health problems may be overlooked and go untreated.

Organization

Diagnoses and problems can be sorted and organized more readily than findings. The dentist typically lists the important issues first, such as the chief complaint, with other diagnoses following in order of significance. This process of prioritization sets the stage for developing a sequenced treatment plan.

Professional competence

Documenting diagnoses in the record provides an important safeguard against avoiding the appearance of providing unnecessary treatment. In the event of malpractice litigation, dentists who list this information fare better than those who do not. A discussion of standardized codes is featured in the In Clinical Practice box.

Diagnostic codes

As discussed throughout this chapter, the dentist should always have arrived at a diagnosis, whether definitive or tentative, before beginning the patient’s treatment. Each treatment procedure should be rationalized with a specific diagnosis or set of diagnoses. The benefits of utilizing a standardized system of diagnostic nomenclature and coding are significant and include: accurate data recording; effective and efficient communication; treatment outcome tracking; evaluation of treatment outcomes; quality improvement; and facilitation of third party accounting, billing, and payment. As dental patients become more medically complex, frequently with multiple healthcare providers and insurers, standardized terminology and coding for diagnoses and treatment procedures have become essential. The increasing use of electronic health records (EHR) and electronic dental records (EDR) requires encoded standard health terminology. Universally accepted diagnostic codes will provide a foundation for integrating interprofessional (IP) patient care (see Chapter 5 ), and coordinating services between dental care providers and other healthcare providers.

Currently, three diagnostic coding systems are used in U.S. dentistry: the dental subset of SNOMED CT known as SNODENT; the Code on Dental Procedures and Nomenclature also referred to as Current Dental Terminology (CDT); and the International Classification of Diseases—Clinical Modification, Release 9 (ICD-9-CM).

The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, also called the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), evolved from the International Lists of Diseases and Causes of Death created and revised decennially beginning in the late 19th century (1891). After World War II, the World Health Organization (WHO) assumed the responsibility of maintaining and updating these lists. The tenth version, ICD-10, has been adopted by many WHO member countries since 1994. In the U.S., ICD-10-CM and ICD-10-PCS (ICD-10 procedure coding system) is scheduled for implementation in 2015. ICD-11 is currently under development by the WHO and implementation is expected by 2017.

CDT has been developed by the American Dental Association (ADA) to achieve uniformity, consistency, and specificity in accurately reporting dental treatment and to enable efficient processing of dental claims. The first CDT Code set was published in 1969 as the Uniform Code on Dental Procedures and Nomenclature in The Journal of the American Dental Association . Since then, updates have been released periodically by the ADA. In 2000 the CDT Code was designated as a HIPAA standard code set. Any claim submitted on a HIPAA standard electronic dental claim form must use dental procedure codes from the version of the CDT Code in effect on the date of service. Increasingly, insurance companies are requiring a specific diagnosis or diagnoses for each dental procedure. In 2012 the ADA updated the dental claim form to support reporting up to four diagnosis codes per dental procedure. SNODENT (see later) is the best resource for the diagnosis codes. The claim form also contains ICD-9 CM and ICD-10 CM diagnosis codes for medical procedures provided by dentists who are eligible providers.

The SNOMED Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT) document was released in 2002 as a convergence of The College of American Pathologists (CAP) SNOMED reference terminology (SNOMED RT) and the United Kingdom’s Clinical Terms Version 3 (formerly known as the Read Codes). The CAP began the development of Systematized Nomenclature of Pathology (SNOP) in 1965. In 1974 SNOP was expanded from a pathology-centric nomenclature to a broader version called the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED). SNOMED RT was the 2000 updated version, containing a broad range of basic sciences, laboratory, and specialty medicine terminology for the EHR environment and cross-mapped to ICD-9 CM. In 2007 an international nonprofit organization, the International Health Terminology Standards Development Organization (IHTSDO), was created in Denmark to continue the updating, maintenance, and distribution of the SNOMED CT.

Both SNOMED CT and ICD have included only limited terminology for dental problem description and diagnosis. The ADA began development of the Systematized Nomenclature of Dentistry (SNODENT) in the 1990s. In 2007 the ADA began the process of updating SNODENT for electronic dental record use and for inclusion as a subset of SNOMED CT by cross-mapping SNOMED CT, ICD-9, and ICD-10. In 2012 the ADA and IHTSDO reached a licensing agreement for use of SNODENT as the dental subset of SNOMED CT. Eligible dental schools and practitioners who participate in Medicare and/or Medicaid may be required to use SNODENT for dental service claims, just as SNOMED CT is required terminology for these same payers. As a component of IHTSDO, the ADA is collaborating with the WHO to ensure that the oral health codes within ICD-11 are complete and are comparable and compatible with SNODENT.

As this process unfolds, it is anticipated that the use of standardized and encoded diagnostic terminology will become the norm in dental practice.

For further discussion of this topic, the reader is referred to Kelly Soderlund: SNODENT takes the global stage: ADA and WHO evaluating latest version of International Classification of Diseases, ADA News April 11, 2013. Or visit: http://www.ada.org and http://www.ihtsdo.org .

Patient education

At the conclusion of the examination, the dentist should inform the patient about his or her oral condition. A list of diagnoses and problems provides a convenient and straightforward way to share this information. Discussing diagnoses and problems with the patient becomes part of the process of obtaining informed consent to provide treatment.

Standard of care

Dental professional organizations typically include in their codes of ethical principles the expectation that the dentist will arrive at a diagnosis and inform the patient of that diagnosis before beginning treatment. Most dental boards now explicitly require a documented diagnosis of the patient’s condition before the dentist begins treatment.

The comprehensive patient diagnosis

The patient’s comprehensive diagnosis list or patient diagnosis is a compilation of any of the patient’s problems or concerns that require (1) recognition, (2) management, or (3) treatment .

Not all diagnoses will require therapeutic or surgical intervention at the time of initial treatment planning. Some diagnoses need only to be identified and recognized at this juncture. A frequently encountered example is the patient with an amalgam tattoo. Any pigmented lesion in the oral cavity warrants our attention—but when the history, clinical appearance, and lack of symptoms are consistent with a diagnosis of an amalgam tattoo, the usual course of action will be to record the presence, location, and appearance of the tattoo and to compare that description with the appearance of the tattoo at future periodic (recall) visits. Initial photographic images can facilitate this process. The diagnosis is explained to the patient and the patient is reassured as to the benign nature of the discoloration. No biopsy is necessary at this time.

A patient who, according to the American Heart Association guidelines, is at the highest risk for endocarditis will require antibiotic premedication for dental procedures for which tissue manipulation is expected. By taking into account issues relating to the patient’s general health (i.e., the potential for endocarditis) we are not treating the patient’s medical condition, but rather we are managing the patient’s general health needs by providing dental treatment in a manner consistent with professional practice standards and in the patient’s best general health interests.

The majority of a patient’s oral health diagnoses will be treated through some form of direct chemotherapeutic, surgical, or restorative intervention.

Most patient diagnoses can be expected to fall into the following categories. While it would be extremely unusual for any one patient to have issues in all of these categories, the general dentist can expect to regularly encounter all of these diagnoses in his or her family of patients ( Box 2-1 ):

-

The patient’s chief concern

-

General health issues that impact on dental treatment

-

Diagnoses that evolve from the patient’s oral health history

-

Diagnoses that evolve from the patient’s personal history

-

Findings from the intraoral and extraoral exam

-

Findings from the radiographic exam

-

Disorders of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) complex

-

Skeletal and occlusal abnormalities

-

Periodontal pathology

-

Pathology of the pulp or apical periodontium

-

Caries and noncarious abnormalities of the teeth

-

Esthetic concerns and problems

-

Defects or problems with restorations, an oral prosthesis and/or implants

The following is an example of a diagnosis list for a dental patient. For clarity, acronyms and abbreviations are either avoided or explained. Tooth numbers are not included so as to avoid confusion with varying numbering systems. In this example, the diagnoses are generally broad (not tooth or surface specific) with the presumption that specific clinical findings relating to tooth and surface lesions are identified in the patient record.

- 1.

Chief concern: fractured maxillary right lateral incisor with exposed dentin and reversible pulpitis

- 2.

Type 2 diabetes well controlled with oral hypoglycemic

- 3.

Hypertension well controlled with medications

- 4.

Allergic to penicillin and latex

- 5.

Current smoker (30 pack-year smoking history)

- 6.

Sporadic dental treatment history; last cleaning 3 years ago

- 7.

Actinic keratosis on the lower lip

- 8.

Hyposalivation

- 9.

Multiple primary and secondary carious lesions (see charting for teeth and surfaces)

- 10.

High caries risk

- 11.

Localized moderate marginal periodontitis

- 12.

Gingival recession on the facial surfaces of most posterior teeth

- 13.

Root sensitivity on maxillary right canine

- 14.

Maxillary left second molar with cervical caries penetrating into the pulp—necrotic pulp and chronic apical periodontitis *

- 15.

Partial edentulism

- 16.

Hypererupted maxillary left first molar

- 17.

Upper and lower RPDs (removable partial dentures)—fractured clasp and poor retention with upper RPD

*Current American Academy of Endodontics designation: asymptomatic apical periodontitis (AAP).

Patient diagnosis

Diagnoses and problems

Armed with the significant findings from the examination process, the dentist now begins to assemble a list of diagnoses for the patient. Diagnoses are precise, scientific terms used to describe variations from normal. They can be applied to a systemic disease, such as diabetes, or a specific oral health condition, such as aggressive periodontitis. Other examples of diagnoses include occlusal caries, irreversible pulpitis, squamous cell carcinoma (SCCA), and Class II malocclusion. Often, more than one finding may be necessary to formulate a diagnosis. For example, a tooth that appears darker than the others may or may not be a significant finding. This finding, concurrent with a tooth that tests negative to electric pulp testing and the radiographic appearance of a periapical radiolucency, would strongly suggest pulpal necrosis.

![]() Images in the tables can be viewed larger in the expanded chapter on Evolve.

Images in the tables can be viewed larger in the expanded chapter on Evolve.

Several types of diagnoses are possible. When several findings point clearly to a specific disease entity, the clinician may make a definitive diagnosis, indicating a high level of certainty. On the other hand, when the findings suggest several possible conditions, the process of distinguishing among the list of possibilities is referred to as a differential diagnosis. For example, the differential diagnosis of a lump on the patient’s palate might require differentiation among such possibilities as a maxillary torus, a salivary gland tumor, or an odontogenic infection. Without more information, such as findings from a radiograph or a biopsy result, it may be impossible to reach a definitive diagnosis. A “golden rule” of treatment planning is that a diagnosis should be made before treatment begins. When the diagnosis is uncertain, but it is prudent to begin some type of treatment, a working or tentative diagnosis may be made. Diagnostic tests, consultation with other providers, or reevaluation of the patient will usually be required to either confirm the diagnosis or to change to a new, more definitive, diagnosis.

On many occasions, a precise diagnosis that matches a significant finding may not be achievable. For example, the patient may reveal that he or she has limited funds available for dental treatment. This is a significant finding that may affect the treatment plan but it does not fit the classic definition of a diagnosis. Such issues are typically referred to as problems. Patient problems can be general or specific issues that suggest the need for attention. Common examples of patient problems include dental pain of undetermined origin, fear of dental treatment, or the patient who requires the assistance of a caregiver to brush the teeth.

Benefits of a diagnosis and problem list

After completing the patient examination, the dentist must assemble and organize all the significant findings to create a list of patient diagnoses and problems. This list is then documented in the patient record. The benefits of creating such a list include:

Foundation for the treatment plan

When generating a patient’s treatment plan or plan of care each treatment on the plan must be justified by one or more diagnoses or reasons for treatment . The patient’s diagnosis is the essential basis for any treatment plan. A treatment plan that lacks this foundation is often missing key components. Important patient concerns and/or oral health problems may be overlooked and go untreated.

Organization

Diagnoses and problems can be sorted and organized more readily than findings. The dentist typically lists the important issues first, such as the chief complaint, with other diagnoses following in order of significance. This process of prioritization sets the stage for developing a sequenced treatment plan.

Professional competence

Documenting diagnoses in the record provides an important safeguard against avoiding the appearance of providing unnecessary treatment. In the event of malpractice litigation, dentists who list this information fare better than those who do not. A discussion of standardized codes is featured in the In Clinical Practice box.

Diagnostic codes

As discussed throughout this chapter, the dentist should always have arrived at a diagnosis, whether definitive or tentative, before beginning the patient’s treatment. Each treatment procedure should be rationalized with a specific diagnosis or set of diagnoses. The benefits of utilizing a standardized system of diagnostic nomenclature and coding are significant and include: accurate data recording; effective and efficient communication; treatment outcome tracking; evaluation of treatment outcomes; quality improvement; and facilitation of third party accounting, billing, and payment. As dental patients become more medically complex, frequently with multiple healthcare providers and insurers, standardized terminology and coding for diagnoses and treatment procedures have become essential. The increasing use of electronic health records (EHR) and electronic dental records (EDR) requires encoded standard health terminology. Universally accepted diagnostic codes will provide a foundation for integrating interprofessional (IP) patient care (see Chapter 5 ), and coordinating services between dental care providers and other healthcare providers.

Currently, three diagnostic coding systems are used in U.S. dentistry: the dental subset of SNOMED CT known as SNODENT; the Code on Dental Procedures and Nomenclature also referred to as Current Dental Terminology (CDT); and the International Classification of Diseases—Clinical Modification, Release 9 (ICD-9-CM).

The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, also called the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), evolved from the International Lists of Diseases and Causes of Death created and revised decennially beginning in the late 19th century (1891). After World War II, the World Health Organization (WHO) assumed the responsibility of maintaining and updating these lists. The tenth version, ICD-10, has been adopted by many WHO member countries since 1994. In the U.S., ICD-10-CM and ICD-10-PCS (ICD-10 procedure coding system) is scheduled for implementation in 2015. ICD-11 is currently under development by the WHO and implementation is expected by 2017.

CDT has been developed by the American Dental Association (ADA) to achieve uniformity, consistency, and specificity in accurately reporting dental treatment and to enable efficient processing of dental claims. The first CDT Code set was published in 1969 as the Uniform Code on Dental Procedures and Nomenclature in The Journal of the American Dental Association . Since then, updates have been released periodically by the ADA. In 2000 the CDT Code was designated as a HIPAA standard code set. Any claim submitted on a HIPAA standard electronic dental claim form must use dental procedure codes from the version of the CDT Code in effect on the date of service. Increasingly, insurance companies are requiring a specific diagnosis or diagnoses for each dental procedure. In 2012 the ADA updated the dental claim form to support reporting up to four diagnosis codes per dental procedure. SNODENT (see later) is the best resource for the diagnosis codes. The claim form also contains ICD-9 CM and ICD-10 CM diagnosis codes for medical procedures provided by dentists who are eligible providers.

The SNOMED Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT) document was released in 2002 as a convergence of The College of American Pathologists (CAP) SNOMED reference terminology (SNOMED RT) and the United Kingdom’s Clinical Terms Version 3 (formerly known as the Read Codes). The CAP began the development of Systematized Nomenclature of Pathology (SNOP) in 1965. In 1974 SNOP was expanded from a pathology-centric nomenclature to a broader version called the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED). SNOMED RT was the 2000 updated version, containing a broad range of basic sciences, laboratory, and specialty medicine terminology for the EHR environment and cross-mapped to ICD-9 CM. In 2007 an international nonprofit organization, the International Health Terminology Standards Development Organization (IHTSDO), was created in Denmark to continue the updating, maintenance, and distribution of the SNOMED CT.

Both SNOMED CT and ICD have included only limited terminology for dental problem description and diagnosis. The ADA began development of the Systematized Nomenclature of Dentistry (SNODENT) in the 1990s. In 2007 the ADA began the process of updating SNODENT for electronic dental record use and for inclusion as a subset of SNOMED CT by cross-mapping SNOMED CT, ICD-9, and ICD-10. In 2012 the ADA and IHTSDO reached a licensing agreement for use of SNODENT as the dental subset of SNOMED CT. Eligible dental schools and practitioners who participate in Medicare and/or Medicaid may be required to use SNODENT for dental service claims, just as SNOMED CT is required terminology for these same payers. As a component of IHTSDO, the ADA is collaborating with the WHO to ensure that the oral health codes within ICD-11 are complete and are comparable and compatible with SNODENT.

As this process unfolds, it is anticipated that the use of standardized and encoded diagnostic terminology will become the norm in dental practice.

For further discussion of this topic, the reader is referred to Kelly Soderlund: SNODENT takes the global stage: ADA and WHO evaluating latest version of International Classification of Diseases, ADA News April 11, 2013. Or visit: http://www.ada.org and http://www.ihtsdo.org .

Patient education

At the conclusion of the examination, the dentist should inform the patient about his or her oral condition. A list of diagnoses and problems provides a convenient and straightforward way to share this information. Discussing diagnoses and problems with the patient becomes part of the process of obtaining informed consent to provide treatment.

Standard of care

Dental professional organizations typically include in their codes of ethical principles the expectation that the dentist will arrive at a diagnosis and inform the patient of that diagnosis before beginning treatment. Most dental boards now explicitly require a documented diagnosis of the patient’s condition before the dentist begins treatment.

The comprehensive patient diagnosis

The patient’s comprehensive diagnosis list or patient diagnosis is a compilation of any of the patient’s problems or concerns that require (1) recognition, (2) management, or (3) treatment .

Not all diagnoses will require therapeutic or surgical intervention at the time of initial treatment planning. Some diagnoses need only to be identified and recognized at this juncture. A frequently encountered example is the patient with an amalgam tattoo. Any pigmented lesion in the oral cavity warrants our attention—but when the history, clinical appearance, and lack of symptoms are consistent with a diagnosis of an amalgam tattoo, the usual course of action will be to record the presence, location, and appearance of the tattoo and to compare that description with the appearance of the tattoo at future periodic (recall) visits. Initial photographic images can facilitate this process. The diagnosis is explained to the patient and the patient is reassured as to the benign nature of the discoloration. No biopsy is necessary at this time.

A patient who, according to the American Heart Association guidelines, is at the highest risk for endocarditis will require antibiotic premedication for dental procedures for which tissue manipulation is expected. By taking into account issues relating to the patient’s general health (i.e., the potential for endocarditis) we are not treating the patient’s medical condition, but rather we are managing the patient’s general health needs by providing dental treatment in a manner consistent with professional practice standards and in the patient’s best general health interests.

The majority of a patient’s oral health diagnoses will be treated through some form of direct chemotherapeutic, surgical, or restorative intervention.

Most patient diagnoses can be expected to fall into the following categories. While it would be extremely unusual for any one patient to have issues in all of these categories, the general dentist can expect to regularly encounter all of these diagnoses in his or her family of patients ( Box 2-1 ):

-

The patient’s chief concern

-

General health issues that impact on dental treatment

-

Diagnoses that evolve from the patient’s oral health history

-

Diagnoses that evolve from the patient’s personal history

-

Findings from the intraoral and extraoral exam

-

Findings from the radiographic exam

-

Disorders of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) complex

-

Skeletal and occlusal abnormalities

-

Periodontal pathology

-

Pathology of the pulp or apical periodontium

-

Caries and noncarious abnormalities of the teeth

-

Esthetic concerns and problems

-

Defects or problems with restorations, an oral prosthesis and/or implants

The following is an example of a diagnosis list for a dental patient. For clarity, acronyms and abbreviations are either avoided or explained. Tooth numbers are not included so as to avoid confusion with varying numbering systems. In this example, the diagnoses are generally broad (not tooth or surface specific) with the presumption that specific clinical findings relating to tooth and surface lesions are identified in the patient record.

- 1.

Chief concern: fractured maxillary right lateral incisor with exposed dentin and reversible pulpitis

- 2.

Type 2 diabetes well controlled with oral hypoglycemic

- 3.

Hypertension well controlled with medications

- 4.

Allergic to penicillin and latex

- 5.

Current smoker (30 pack-year smoking history)

- 6.

Sporadic dental treatment history; last cleaning 3 years ago

- 7.

Actinic keratosis on the lower lip

- 8.

Hyposalivation

- 9.

Multiple primary and secondary carious lesions (see charting for teeth and surfaces)

- 10.

High caries risk

- 11.

Localized moderate marginal periodontitis

- 12.

Gingival recession on the facial surfaces of most posterior teeth

- 13.

Root sensitivity on maxillary right canine

- 14.

Maxillary left second molar with cervical caries penetrating into the pulp—necrotic pulp and chronic apical periodontitis *

- 15.

Partial edentulism

- 16.

Hypererupted maxillary left first molar

- 17.

Upper and lower RPDs (removable partial dentures)—fractured clasp and poor retention with upper RPD

*Current American Academy of Endodontics designation: asymptomatic apical periodontitis (AAP).

Common diagnoses

A.

Diagnoses derived from the patient’s chief concern and other concerns

As described in Chapter 1 , the patient interview begins with an investigation of the patient’s chief concern . A chief concern expressed as a request like “I need a check-up and cleaning” would not normally be carried over to the patient’s diagnosis as it would be a routine part of the patient’s plan of care. Any chief concern that will require patient-specific action by the dental team, however, should be included in the diagnosis ( Figure 2-1 ).

A patient who presents to the initial examination visit with a chief concern described as “a toothache” definitely needs to have that problem recorded in the diagnosis. The way the problem is recorded, however, will vary with the findings that are available to the dentist at the initial visit. If, during the course of the initial examination, definitive tooth, pulp, and apical diagnoses can be determined, it will be appropriate to include all those related problems in the patient’s diagnosis. If the diagnosis for the “toothache” is suspected but unconfirmed, it may be listed in the diagnosis as a tentative or working diagnosis. If the diagnosis for the “toothache” is undetermined at the initial exam and it is difficult to even speculate on a diagnosis, it will then be appropriate to include the problem as tooth pain of undetermined origin in the diagnosis list.

Although often the chief concern is not an acute problem, that does not diminish its importance. Certainly, if the patient presents with a chief concern of “I don’t like my smile; my teeth don’t look good” that concern needs to be included in the diagnosis.

A patient may present with more than one concern and may have multiple treatment desires or objectives. Therefore, any patient concern – not just the chief concern – that may need to be addressed by the dental team is appropriate to include in the diagnosis list.

B.

General health diagnoses

A wide variety of diagnoses can be made concerning a patient’s general health condition. Many of these diagnoses will be self-reported by the patient on the general health history questionnaire. The dentist may have additional concerns after reviewing the medication list, interviewing and examining the patient, and evaluating the vital signs. If any findings contradict the patient’s own appraisal/report of his or her general health, it may be necessary to contact the patient’s primary healthcare provider. Similarly, a patient who presents with signs or symptoms of an undiagnosed or untreated medical problem will need to be medically managed before, during, and following dental treatment ( Figure 2-2 ).

Any general health issues that may have an impact on the treatment plan or the delivery of dental treatment should be included in the diagnosis. When possible, an objective qualifier should be added to indicate both the type of problem and the level of disease control.

For example:

-

Asthma with last attack 25 years ago versus asthma with weekly attacks

-

Stable or unstable angina

-

Controlled or uncontrolled hypertension

-

Type 2 diabetes mellitus with the Hb A1C 7.0 measured 1 month ago

-

History of head and neck radiation with total radiation to the jaw bones

-

History of intravenous bisphosphonate use for the last 5 years in conjunction with breast cancer

-

History of deep vein thrombosis – currently taking warfarin

An overview of medical problems and their management in the context of dental treatment is set forth in Chapter 7 (Systemic Phase of Treatment). Selected general health diagnoses are also detailed in Chapters 12 (Patients with Special Needs), and 17 (Geriatric Patients). Additionally, Chapter 13 discusses substance abuse problems; Chapter 14 addresses patients with dental anxiety; and Chapter 15 focuses on psychological disorders.

C.

Patient considerations that influence the treatment plan

Patient considerations are those modifiers to treatment planning that are derived exclusively from information about the patient. The personal history and the oral health history can be a rich source for this information. Additionally, patient considerations will be revealed in the course of conversation over subsequent dental visits as the dental team and the patient become better acquainted. Some patient considerations, especially those that reflect the patient’s motivation and abilities to accept recommendations and execute behavioral changes, will be fully revealed only after considerable time and experience.

Throughout this book, the importance of including and weighing patient considerations in considering treatment options and formulating treatment proposals is emphasized. An understanding of patient choices and preferences is essential to the development of a treatment plan that will be acceptable to the patient and addresses his or her expectations. This understanding is also critical if the patient is to be fully involved in the treatment planning process and not only compliant, but energetically engaged in the treatment process as well. With the patient invested and engaged, the probability of success is also much improved and the patient is more likely to recognize and appreciate the benefits of the treatment that is rendered.

The following is a list of some of the patient considerations that can have significant impact in planning treatment for a patient. Such factors, when they are believed by either the patient or the dentist to limit the scope of treatment or to require modification in the way treatment can be delivered, should be identified and recorded in the patient’s diagnosis:

-

Patient’s level of knowledge relating to oral health issues and problems

-

Patient’s ability to establish and maintain effective oral self-care practices

-

Patient’s motivation to embark on dental treatment and the ability to sustain that effort

-

Sufficient patient physical and mental stamina to engage in treatment in the face of competing personal priorities and family and society demands

-

The resources – including time and money – necessary for participation in the treatment

-

Reliable means of transportation to and from the dental office

Note: Chapter 18 specifically addresses the needs of patients who are motivationally compromised and/or have limited financial resources.

D.

Extraoral diagnoses

When the patient walks (or is assisted) into the dental operatory for an initial oral examination, any tremors, imbalance, or abnormalities of posture, gait, sight, hearing, or cognition will be readily apparent. As discussed in Chapter 1 , the initial oral examination of the dental patient includes taking vital signs and a visual and palpatory assessment of exposed skin surfaces of the head, face, and neck. On occasion, the patient may request an opinion concerning an abnormality that is identified during this stage of the initial examination; for example, the discovery of a colored lesion on the skin that the patient had been previously unaware of. If there is any question about the diagnosis in the dentist or the patient’s mind it will be appropriate for the dentist, as a healthcare provider, to refer the patient to a dermatologist or other clinician for evaluation and treatment. The dentist also should be cognizant of any underlying health problem that may affect the treatment planning or the manner in which dental treatment will be delivered. This section highlights some of the more common conditions that may become apparent during an extraoral examination that are likely to have a significant impact on treatment planning for the patient . The topics in this section are organized and sequenced in the order in which the extraoral examination is usually executed. For a more comprehensive and detailed analysis, the reader is referred to several authoritative textbooks in the Suggested Readings at the end of this chapter.

Abnormalities apparent through general observation

Parkinson’s disease (PD)

This degenerative disorder of the central nervous system causes involuntary uncontrolled movements. The disorder progresses to widespread motor function impairments and sensory, emotional, and cognitive dysfunction.

Classic signs include body rigidity, short dragging footsteps, and trembling hands. These patients often have challenges arranging transportation to the dental office, ambulating to the dental operatory, holding the mouth open during dental procedures, and performing daily oral self-care procedures (see Chapter 17 for more information).

Arthritis

Both osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis may affect multiple joints of the body, causing difficulty in walking and in head and neck movement. Impairment of the dominant hand joints may contribute to ineffective oral hygiene. When the temporomandibular joints are affected, the range of jaw movement may be limited.

Cerebrovascular accident (CVA)

A CVA, also known as a stroke, occurs when there is a disruption in the blood supply and oxygen deprivation to a portion of the brain, causing the death of some brain cells. The immediate cause of the disruption is often a blood clot or thrombus. The patient may exhibit a temporary (and sometimes permanent) speech or motor deficit on the side of the body controlled by the affected portion of the brain. In the dental setting, the patient may manifest aphonia, dysphonia, and hemiplegia, and may have difficulty carrying out the activities of daily living independently. The patient may need assistance with oral hygiene activities.

Neuromuscular disorders

Neuromuscular disorders are a group of diseases related to either muscles, nerves, or both that result in impaired movement and, with some conditions, sensory or other neurologic dysfunctions. These disorders can be categorized based on the cause. Examples include multiple sclerosis, Huntington disease, myasthenia gravis, muscular dystrophy, and idiopathic inflammatory myositis. These disorders may pose challenges to oral healthcare depending on the severity of the disease and the effects of treatment medications.

Vital signs irregularities

Hypertension (high blood pressure).

Patients may present at the initial visit with a history of hypertension, or hypertension may be suspected when the dental team assesses the blood pressure (see Chapter 1 ). When hypertension has no known cause it may be identified as essential hypertension, primary hypertension, or idiopathic hypertension. Hypertension is a risk factor for heart attack, stroke, and chronic kidney disease. Its high prevalence and low rate of diagnosis and treatment has been a major public health concern. Oral healthcare providers have the responsibility to refer patients with persistent elevated blood pressure, including those resistant to treatment, to a physician for evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment. A high blood pressure reading in the dental clinic may indicate the presence of a significant cardiovascular conditions such as left ventricular hypertrophy, aortic stenosis, or conduction defects that warrant pretreatment evaluation by a cardiologist. The patient’s cardiologist may wish to provide treatment, such as medication modification, to avoid perioperative cardiovascular complications. In addition, many antihypertensive medications have adverse oral effects, most notably hyposalivation, that are relevant to oral healthcare and treatment planning.

Irregular pulse (arrhythmia; includes rhythm, intensity, rate abnormalities).

Arrhythmia is a general term for a group of conditions characterized by an irregular heartbeat. Some arrhythmias are genetic and others are acquired. Some are trivial; others can be life threatening. Severe arrhythmia can be precipitated by intense pain or by a variety of drugs or drug-drug interactions. The patient’s underlying cardiac condition may also play a role in the precipitation of a life-threatening arrhythmia. For example, in susceptible patients certain antibiotics can cause QT elongation and may precipitate a Torsade de pointe (Tdp), a severe ventricular fibrillation, and sudden cardiac arrest. To avoid precipitating severe arrhythmia it is important that the dentist identify patients who are at risk through their health and medication histories.

Abnormalities apparent on the hands or exposed skin surfaces

Arthritic hands

The hands ( Figure 2-3 ) can provide insights into the patient’s general health. Swollen and inflamed joints can be signs of many autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis. The disease or its treatment may influence oral health or oral healthcare; for example, additional help may be needed for effective oral hygiene; treatment modification may be necessary.

Bruises (ecchymosis)

Bruises on the skin ( Figure 2-4 ) can be a sign of an acquired or hereditary bleeding disorder and may warrant further investigation or treatment plan modification. They can also be the result of trauma or physical abuse.

Splinter hemorrhages

![]() Splinter hemorrhages are dots or vertical streaks of hemorrhages under the nails ( eFigure 2-1 ). Nail trauma is the most common cause but skin disorders, systemic diseases, or medication use can also be responsible. Examples of systemic diseases that cause the condition include nail psoriasis, endocarditis, and systemic lupus erythematosus. Aspirin and warfarin are medications that have been reported to cause splinter hemorrhages.

Splinter hemorrhages are dots or vertical streaks of hemorrhages under the nails ( eFigure 2-1 ). Nail trauma is the most common cause but skin disorders, systemic diseases, or medication use can also be responsible. Examples of systemic diseases that cause the condition include nail psoriasis, endocarditis, and systemic lupus erythematosus. Aspirin and warfarin are medications that have been reported to cause splinter hemorrhages.

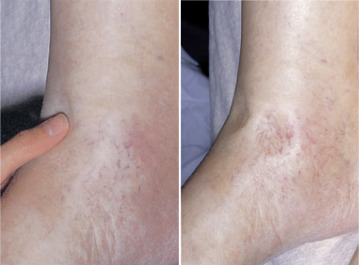

Pitting (or dependent) edema

![]() Pitting edema is an abnormal accumulation of fluid in the extracellular space of lower limb tissue resulting in swelling that can be dimpled with finger pressure ( eFigure 2-2 ). This may occur during pregnancy or may be associated with serious health problems such as congestive heart failure, kidney failure, or liver cirrhosis.

Pitting edema is an abnormal accumulation of fluid in the extracellular space of lower limb tissue resulting in swelling that can be dimpled with finger pressure ( eFigure 2-2 ). This may occur during pregnancy or may be associated with serious health problems such as congestive heart failure, kidney failure, or liver cirrhosis.

Nevi

![]() It is not uncommon to find dark brown or black macules or papules on the skin of the face and neck ( eFigure 2-3 ). The most common diagnosis of these lesions is nevi (plural for nevus). These most common benign tumors of the skin consist of clusters of nevus cells in the epidermis or dermis. By examining their clinical presentation, nevi can be differentiated from other common benign lesions of skin, such as dermatosis papulosa nigra or seborrheic keratosis, or from more serious conditions, such as malignant melanoma, pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCCA), or SCCA. Oral healthcare providers play an important role in recognizing and identifying these pigmented lesions. When clinical findings are not discriminatory, referral to a dermatologist for evaluation and biopsy is indicated.

It is not uncommon to find dark brown or black macules or papules on the skin of the face and neck ( eFigure 2-3 ). The most common diagnosis of these lesions is nevi (plural for nevus). These most common benign tumors of the skin consist of clusters of nevus cells in the epidermis or dermis. By examining their clinical presentation, nevi can be differentiated from other common benign lesions of skin, such as dermatosis papulosa nigra or seborrheic keratosis, or from more serious conditions, such as malignant melanoma, pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCCA), or SCCA. Oral healthcare providers play an important role in recognizing and identifying these pigmented lesions. When clinical findings are not discriminatory, referral to a dermatologist for evaluation and biopsy is indicated.

Seborrheic keratosis

![]() Seborrheic keratoses ( eFigure 2-4 ) are light or dark brown lesions that are flat or slightly elevated on the skin of older individuals. The lesions vary in size but are usually less than 1 cm in diameter and have a velvety to finely verrucous surface. The dentist should be able to differentiate this condition from premalignant or malignant skin lesions; if in doubt, the patient should be referred to a dermatologist.

Seborrheic keratoses ( eFigure 2-4 ) are light or dark brown lesions that are flat or slightly elevated on the skin of older individuals. The lesions vary in size but are usually less than 1 cm in diameter and have a velvety to finely verrucous surface. The dentist should be able to differentiate this condition from premalignant or malignant skin lesions; if in doubt, the patient should be referred to a dermatologist.

Solar (or actinic) cheilosis and solar keratosis

![]() Solar keratosis is a premalignant skin condition caused by sun damage and usually occurs in older individuals with light complexions who have experienced prolonged sunlight exposure, causing the skin to become scaly, rough, and slightly red and elevated. Solar cheilosis is solar keratosis of the lower lip ( eFigure 2-5 ); it appears vermilion with indistinct mucocutaneous borders. The dental team should recommend strategies to prevent the development of lip or skin cancer including reducing sun exposure, wearing sun protective clothing, and use of applied sun block agents.

Solar keratosis is a premalignant skin condition caused by sun damage and usually occurs in older individuals with light complexions who have experienced prolonged sunlight exposure, causing the skin to become scaly, rough, and slightly red and elevated. Solar cheilosis is solar keratosis of the lower lip ( eFigure 2-5 ); it appears vermilion with indistinct mucocutaneous borders. The dental team should recommend strategies to prevent the development of lip or skin cancer including reducing sun exposure, wearing sun protective clothing, and use of applied sun block agents.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCCA)

![]() BCCA is a common neoplasm often found on the skin of adults who have a history of long exposure to sunlight ( eFigure 2-6 ). In spite of being malignant, this condition rarely metastasizes. The patient should be referred to a dermatologist for definitive diagnosis and treatment.

BCCA is a common neoplasm often found on the skin of adults who have a history of long exposure to sunlight ( eFigure 2-6 ). In spite of being malignant, this condition rarely metastasizes. The patient should be referred to a dermatologist for definitive diagnosis and treatment.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCCA)

![]() SCCA, a malignant neoplasm of epidermal or epithelial origin, has potential for distant metastasis ( eFigure 2-7 ). Although less common than BCCA on the skin of the head and neck, it has a significantly higher morbidity and mortality. Early detection and treatment is the key to survival. Oral health professionals should be prepared to recognize a variety of clinical presentations of early SCCA. If detected, timely referral for further evaluation is warranted.

SCCA, a malignant neoplasm of epidermal or epithelial origin, has potential for distant metastasis ( eFigure 2-7 ). Although less common than BCCA on the skin of the head and neck, it has a significantly higher morbidity and mortality. Early detection and treatment is the key to survival. Oral health professionals should be prepared to recognize a variety of clinical presentations of early SCCA. If detected, timely referral for further evaluation is warranted.

Melanoma

![]() Melanoma, a malignant neoplasm of melanocytes in the basal layer of the epidermis and epithelium, occurs primarily in the skin of the head and neck region ( eFigure 2-8 ). Excessive exposure to sunlight is a major risk factor. Although melanoma rarely occurs in the oral mucosa, given its serious nature, it must be included in the differential diagnosis of any intraoral pigmented lesion.

Melanoma, a malignant neoplasm of melanocytes in the basal layer of the epidermis and epithelium, occurs primarily in the skin of the head and neck region ( eFigure 2-8 ). Excessive exposure to sunlight is a major risk factor. Although melanoma rarely occurs in the oral mucosa, given its serious nature, it must be included in the differential diagnosis of any intraoral pigmented lesion.

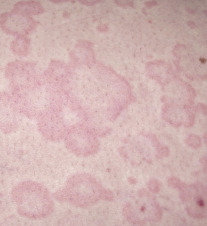

Urticaria

![]() Urticaria is a transient skin condition, also known as hives, characterized by red or white bumps on the skin with intense itching ( eFigure 2-9 ) . The most common cause is an Ig-E mediated allergic reaction to drugs or food. A less common cause can be an autoimmune disease in which the hives come and go repeatedly over months or years. Emotional stress, temperature, and sun exposure have also been linked to episodes of hives. In many cases the cause remains unknown.

Urticaria is a transient skin condition, also known as hives, characterized by red or white bumps on the skin with intense itching ( eFigure 2-9 ) . The most common cause is an Ig-E mediated allergic reaction to drugs or food. A less common cause can be an autoimmune disease in which the hives come and go repeatedly over months or years. Emotional stress, temperature, and sun exposure have also been linked to episodes of hives. In many cases the cause remains unknown.

Angioedema

![]() Although a result of the same mechanisms characteristic of hives, in which the edema is localized and limited to the superficial portion of the dermis, angioedema involves a wider and deeper portion of the dermis and subdermis, resulting in swelling over a larger area ( eFigure 2-10 ). The causes of angioedema are similar to those of hives. Both are short-lived phenomena, lasting only a few hours. A local anesthetic may be the cause of angioedema and of anaphylaxis—a potentially life-threatening medical emergency (see Malamed’s Medical Emergencies in the Dental Office for in-depth discussion).

Although a result of the same mechanisms characteristic of hives, in which the edema is localized and limited to the superficial portion of the dermis, angioedema involves a wider and deeper portion of the dermis and subdermis, resulting in swelling over a larger area ( eFigure 2-10 ). The causes of angioedema are similar to those of hives. Both are short-lived phenomena, lasting only a few hours. A local anesthetic may be the cause of angioedema and of anaphylaxis—a potentially life-threatening medical emergency (see Malamed’s Medical Emergencies in the Dental Office for in-depth discussion).

Contact dermatitis (dermatitis medicamentosa)

![]() Contact dermatitis is a T cell-mediated delayed hypersensitivity reaction in which an antigen comes into contact with the skin and is linked to skin protein, forming an antigen complex that leads to sensitization ( eFigure 2-11 ). Upon re-exposure of the epidermis to the offending antigen, the sensitized T cells initiate an inflammatory cascade. Within 24 to 48 hours after contact, pruritic erythema, vesicles, and bullae form. As the inflammation dwindles, a crust forms on the affected area, which heals in about three weeks.

Contact dermatitis is a T cell-mediated delayed hypersensitivity reaction in which an antigen comes into contact with the skin and is linked to skin protein, forming an antigen complex that leads to sensitization ( eFigure 2-11 ). Upon re-exposure of the epidermis to the offending antigen, the sensitized T cells initiate an inflammatory cascade. Within 24 to 48 hours after contact, pruritic erythema, vesicles, and bullae form. As the inflammation dwindles, a crust forms on the affected area, which heals in about three weeks.

Common antigens causing this reaction include poison ivy, nickel, and some fragrances. Patients who are sensitive to acrylic or metals in dental prostheses may develop this reaction.

A variety of topical medicaments, including antibiotics, steroids, anesthetics, and antifungals are frequently encountered as the cause of allergic contact dermatitis. Neomycin and lidocaine are most often reported.

Herpes zoster (shingles)

![]() Herpes zoster is a skin eruption spreading in a beltlike pattern and is a recurrent episode of latent varicella zoster virus infection in individuals who contracted chickenpox in childhood and carry latent viruses in the sensory nerve ganglia ( eFigure 2-12 ). Reactivation occurs spontaneously later in adult life when the immune system may be suppressed. The lesions of herpes zoster are localized to distribution in one or more sensory nerves with sharp demarcation. When occurring in the head region, the lesions follow the distribution of the trigeminal nerve branches. Intraoral cases may be extremely painful and debilitating and, in severe form, may result in destruction of periodontal tissues on the affected side (see Suggested Readings at the end of the chapter for information on the diagnosis and management of herpes zoster).

Herpes zoster is a skin eruption spreading in a beltlike pattern and is a recurrent episode of latent varicella zoster virus infection in individuals who contracted chickenpox in childhood and carry latent viruses in the sensory nerve ganglia ( eFigure 2-12 ). Reactivation occurs spontaneously later in adult life when the immune system may be suppressed. The lesions of herpes zoster are localized to distribution in one or more sensory nerves with sharp demarcation. When occurring in the head region, the lesions follow the distribution of the trigeminal nerve branches. Intraoral cases may be extremely painful and debilitating and, in severe form, may result in destruction of periodontal tissues on the affected side (see Suggested Readings at the end of the chapter for information on the diagnosis and management of herpes zoster).

Abnormalities in the head, face, and neck region

Thyroid gland enlargement/goiter

Enlargement of the thyroid gland may be diffuse or nodular and may be unilateral or bilateral ( Figure 2-5 ). An enlarged thyroid gland may function normally or may be associated with hyper- or hypothyroidism. When a thyroid enlargement is newly discovered in the course of the initial oral examination, referral to an endocrinologist or primary medical care provider is on order. Laboratory testing can reveal the status of the gland. Visibly prominent thyroid enlargement, or goiter, may also be classified in terms of the cause, which can be iodine deficiency, autoimmune disease (Hashimoto thyroiditis, Graves’ disease), or benign or malignant neoplasia. The dental team must be attentive to the possibility that a patient with a goiter and clinical signs of hyperthyroidism may develop an acute life-threatening medical emergency while in the dental chair (see Malamed’s Medical Emergencies in the Dental Office ).

Lymphadenopathy (lymphadenitis/lymphoid hyperplasia/calcified lymph nodes)

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses