13 Cleft lip and palate, and syndromes affecting the craniofacial region

A syndrome is the association of several clinically recognizable signs and symptoms, which can occur together in an affected individual. A large number of syndromic conditions involve the craniofacial region (Gorlin et al, 2001) and these can be broadly subdivided into:

Teratogenic agents come in many forms and can include:

Identifying candidate genes for genetic conditions

Elucidating the genetic basis of an inherited condition is not a straightforward task. The human genome contains over 3 billion base pairs within the entire DNA sequence and some genetic disorders can arise from a change in only a single one of these. One of the main obstacles is the location and identification of the causative gene, a process that has become easier with advances in molecular biology and bioinformatics (Box 13.1).

Box 13.1 The human genome project

Publication of the draft human genome sequence (Lander et al, 2001; Venter et al, 2001) has provided an important global resource that will have an effect upon all our lives. Within the human genome there are approximately 30,000 genes distributed across the 23 chromosomes and access to this sequence information has important implications for molecular medicine. In particular, geneticists are now able to identify disease genes and position them within the genome much more easily. A candidate sequence can be entered into sophisticated online browsers and the whole human DNA sequence searched in a matter of minutes. This knowledge is also allowing the development of more rapid and specific tests for the presence of, or susceptibility to certain genetic diseases; which will lead to earlier diagnosis and hopefully treatment of these conditions. In addition, knowledge gained from the human genome will allow progress to be made in therapeutics, with the design of drugs that function at the molecular level and target the specific causes of the disease rather than simply controlling the effects. Finally, the sequence is also an invaluable resource for biologists, providing valuable insight into human evolution and diversity.

Cleft lip and palate

Clefts involving the lip and/or palate (CLP) or isolated clefts of the palate (CP) are the commonest congenital anomaly to affect the craniofacial region in man (Fraser, 1970). They represent a complex phenotype and reflect a failure of the normal mechanisms involved during early embryological development of the face. In human populations CLP and CP can be broadly subdivided into:

Classification

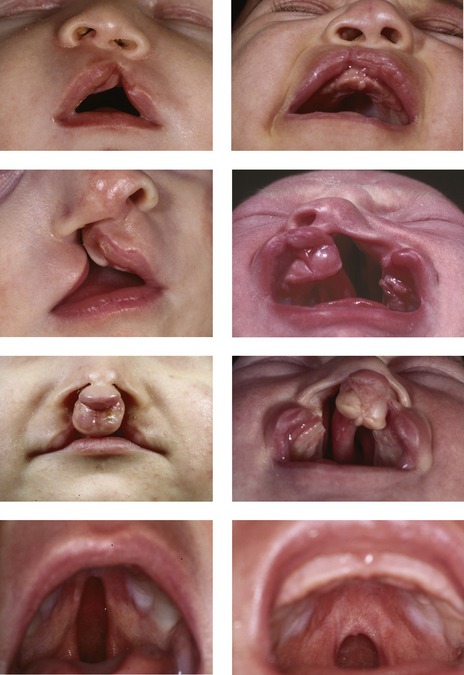

A number of formal classifications have been described for CLP and CP; however, the clinical presentation of these conditions is so variable that a specific description of each individual case is more useful (Fig. 13.1).

Epidemiology

Aetiology

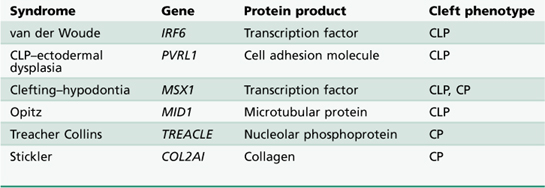

Whilst a number of causative genes have been identified for different types of syndromic CLP and CP (Table 13.1), the aetiology and pathogenesis of nonsyndromic forms are poorly understood. This is a reflection of the multifactorial nature of these conditions, being the result of genetic and environmental interactions affecting development of the face at specific time points during embryogenesis. It has been suggested that up to fourteen different genetic loci may be involved in nonsyndromic CLP, which means that very large and genetically pure sample sizes are required to identify specific causative genes (Lidral & Murray, 2004).

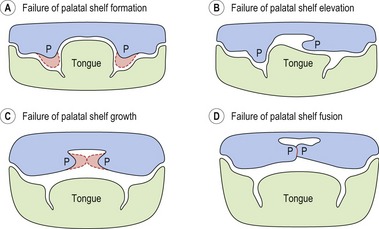

At the embryological level, perturbations in a variety of mechanisms during facial development are known to cause clefting (Fig. 13.2). A growing number of mutant mouse strains that exhibit CP (and to a lesser extent, CLP) have now been generated and these continue to provide a host of candidate genes for the human condition (Gritli-Linde, 2007; Jiang et al, 2006).

Treatment

The clinical management of children born with clefting is most effective when carried out by a fully integrated team, in a centralized unit that treats a high number of patients (Box 13.2). The modern cleft team therefore includes a number of key members, in addition to other specialists who may be involved with long-term care (Table 13.2).

Box 13.2 Providing care for patients with orofacial clefting in the United Kingdom

This concern led to the establishment of a Clinical Standards Advisory Group (CSAG) national investigation into cleft care in the UK. This study reported upon clinical outcome in a total of 457 5- and 12-year-old children affected by nonsyndromic unilateral CLP (Sandy et al, 1998). On the basis of this investigation, the CSAG Cleft Lip and Palate Committee made a number of recommendations regarding the future provision of cleft care in the UK:

Birth

Giving birth to a child affected by a cleft can be a distressing experience for the parents, particularly if this condition has not been diagnosed in utero (Fig. 13.3). A multitude of emotions can occur, including shock, anger, guilt, grief and even rejection. It is important that adequate support is given to the parents and that a bond is quickly established between the parents and child.

Presurgical orthopedics

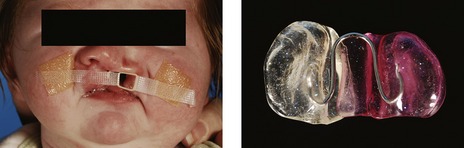

A period of active presurgical orthopedic alignment of the cleft alveolar segments is occasionally carried out in the neonate to reduce the size of the cleft defect and facilitate surgical repair. Specialized facial strapping or orthodontic plates (Fig. 13.4) are used, which can be passive or active and help mould or reposition the divided facial and maxillary segments. In particular, these plates have been used for:

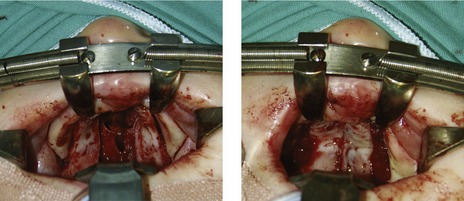

Surgical repair of cleft lip and palate

A number of individual surgical techniques for repairing the embryonic deficits associated with both the lip and palate have been described. However, evaluating which technique, sequence or timing will provide optimum results is difficult and currently no true consensus for any of these criteria exists (Roberts-Harry & Sandy, 1992; Sandy & Roberts-Harry, 1993).

It is clear from comparative studies that facial growth is compromised in operated cleft subjects when compared with those from unoperated samples, particularly those that have undergone palatal repair (Mars & Houston, 1990). The goal of surgical correction is to minimize any potential growth discrepancy, whilst maximizing the aesthetic and functional outcome.

Lip repair

Surgical repair of cleft lip is usually carried out between 3 and 6 months of age as a single procedure (Fig. 13.6), the exact age being dictated by surgeon preference. Classically, the rule of ‘tens’ has been used, with surgery only taking place once the child is at least 10 weeks old, 10 pounds in weight, and having a haemoglobin level of 10%. However, waiting until these criteria are achieved can delay surgery and it has been argued that this can cause problems with both parent–infant bonding and early growth and development. Indeed, advances in neonatal care and paediatric anaesthesia have made it possible to perform cleft surgery during the neonatal period, although there is currently no clear evidence to suggest that this is particularly advantageous (Schendel, 2000).

Bilateral cleft lip is also repaired with a single procedure, involving simultaneous correction of the lip, nose and alveolus (Mulliken, 2000). The upper lip orbicularis oris muscle must be freed from each lateral cleft element and repaired in the midline anterior to the premaxilla.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses