Psychology, p. 328).

• Specialist feeding and nursing advice should be implemented at the time of birth.

• The child and parent should be seen in a multidisciplinary outpatient clinic soon after birth by team members who will be involved in their long-term care.

• Details of surgery should be discussed at this outpatient visit and dates for surgery provided where appropriate.

• The parents should be taken to see the ward to familiarize them with the hospital facilities.

Genetic advice

• All parents given the option of genetic counselling at birth (particularly important if syndromic diagnosis is suspected).

• Traditionally risk has been given as a percentage:

• risk of having a second child with cleft lip and/or palate—4%;

• risk of having a third child—10%;

• risk if a member of the family has CLP to a first-degree relative—2%;

• risk if a member of the family has CLP to a second-degree relative—0.7%;

• risk if a member of the family has CLP third-degree relative—0.3%.

• Norwegian study has shown:

• relative risk of cleft recurrence in first-degree relatives is 32 for any cleft lip and 56 for cleft palate alone;

• risk of clefts in children of affected mothers is similar to the risk of clefts in children of affected fathers;

• the parent–offspring risk is similar to the sibling–sibling risk;

• association between cleft severity and patient’s sex;

• does not affect the risk of having a cleft.

• Genetic counselling recommended to young adults with cleft lip and/or palate.

Management of lip

Principles

• Clefts of the lip cause cosmetic and functional problems.

• Functional problems include impairment:

• in the production of bilabial sounds (pa, pi);

• of maxillary growth because of scar constriction.

• Babies with isolated cleft lip can usually feed normally, although they may have difficulty creating an adequate lip seal.

Anatomical defects in UCLP include:

• Discontinuity of skin, muscle, and oral mucosa of the upper lip on cleft side.

• Vertical soft tissue deficiency on medial aspect of the cleft.

• Abnormal muscle insertions into nasal spine and alar base.

• Alveolar cleft in region of the canine tooth.

• Defect in primary palate anterior to the incisive foramen.

• Rotation of septum, columella, and nasal spine away from the cleft.

• Separation of domes of the alar cartilages at the nasal tip and kinking of the lateral crus on the cleft side.

• Dislocation of lower and upper lateral cartilages on the cleft side.

• Displacement of alar base in all three planes of space.

• Displacement and flattening of the nasal bone on the cleft side.

Anatomical defects in BCLP include:

• Discontinuity of skin, muscle, and oral mucosa of the upper lip bilaterally.

• Bilateral defect of alveolus and anterior palate.

• Central segment consisting of prolabium and pre-maxilla with short columella.

• Lack of orbicularis oris continuity.

• Collapse of lateral palatal segments behind pre-maxilla.

• Alar domes and middle crura are splayed, caudally rotated (bucket handle), and subluxed from their normal anatomic position overlying upper lateral cartilages.

Surgical options

• Lip repair is usually carried out at 3–5 months in UK.

• Neonatal lip repair, while still practised in some units abroad, has fallen into disrepute in the UK.

• Many different protocols for lip and palate repair worldwide.

• The following protocols and timings reflect practice in most UK cleft centres.

Unilateral cleft lip and palate

• The lip, nose, and anterior palate are repaired at the first surgery at 3–5 months of age in healthy children.

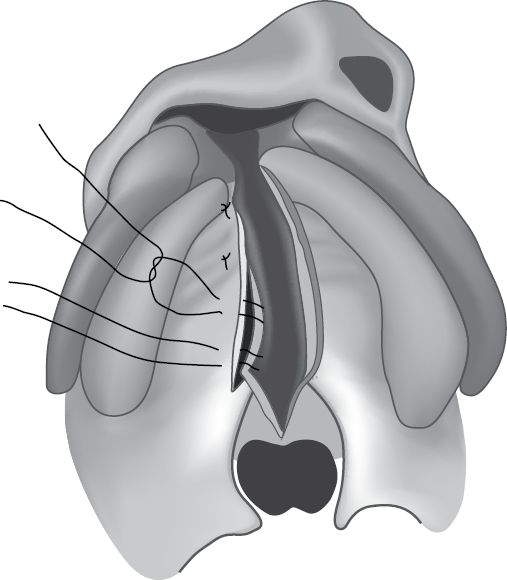

• Anterior palate is repaired with an unlined turnover flap from the vomer (popularized by surgeons in Oslo, Norway) (Fig. 7.1).

Fig. 7.1 Vomer flap for hard palate repair in a right unilateral cleft of the lip and palate.

Important steps in lip repair include:

• Skin incision design.

• Subperiosteal mobilization.

• Muscle repair.

• Nasal floor restoration.

• Alar base positioning and primary nasal dissection.

Design of skin incisions important to accomplish:

• Symmetry.

• Equal lip length.

• Natural appearance of the cupid’s bow.

• Inconspicuous scarring and restoration of the nostril floor.

Many different techniques have been described for lip repair:

• Straight-line techniques (Rose–Thompson).

• Rotation advancement techniques (Millard, Delaire).

• Lower lip Z-plasties (Tennison–Randall).

• Combinations of these.

Individual techniques have advantages and disadvantages:

• Millard (Fig. 7.2):

• scar mimics philtral column on cleft side;

• reconstructs nasal sill;

• allows some leniency in surgical technique (cut as you go);

• may result in short lip on cleft side;

• scar crosses philtral column at nasal base.

• Tennison (Fig. 7.3):

• useful for repairing a wide cleft;

• may result in a long lip;

• scar crosses philtral column inferiorly.

Many now use a combination of these two techniques to take advantage of the strengths of each technique and discard the weaknesses (Fig. 7.4).

Fig. 7.2 Millard lip repair.

Fig. 7.3 Tennison lip repair.

Fig. 7.4 Combination of Millard and Tennison repair.

• Radical subperiosteal mobilization of tissues of the cleft side (which includes incision through inelastic periosteal layer) to orbital rim, zygomatic process, and pyriform rim. It is important to ensure that muscle and skin is closed without undue tension; this also aids in accurate repositioning of the alar base.

• Dissection and repair of orbicularis oris muscle.

• Skin of the lip is dissected off the muscle medially and laterally.

• Muscle repaired with resorbable or non-resorbable sutures.

• Primary bone grafting or gingivoperiosteoplasty (GPP; at the time of lip repair) is not widely practised in UK.

• Primary bone grafting is thought to impair growth.

• GPP requires pre-surgical orthopaedics to bring the alveolar segments into close apposition.

• Pre-surgical orthopaedics for unilateral cleft lip and palate patients is not routinely carried out in UK.

• Repair of the nose (not done by all in UK) is carried out by:

• separating skin from the alar cartilage on the cleft side (as described by McComb and Andel);

• approached both from lateral and medial aspects of the alar cartilage through the skin incisions already made for the lip repair;

• repositioned structures of the nose are maintained using either buried slow-resorbing sutures (e.g. PDS) or external tie-over splints.

Bilateral cleft lip and palate

• Very little conformity (2008 surgical interest group meeting) in UK about:

• use of pre-surgical orthopaedics;

• technique for repair;

• timing of repair.

• Formal surgical repair is often preceded by pre-surgical orthopaedics to reposition the premaxilla posteriorly and align the lateral alveolar segments.

Principles of repair

• Symmetry should be maintained meaning that repair of both sides should occur simultaneously (asynchronous lip repair is practised by three units in UK and Ireland).

• Establish primary muscle continuity (if undue muscle tension exists at time of primary repair then final muscle repair is deferred for about 9 months to a year).

• Median tubercle may be reconstructed from either the prolabium (if patient has a well-developed white roll on the prolabium) or from the lateral lip elements (if there is a poorly developed white roll on the prolabium).

• Reconstruction of the labial sulcus from the prolabial mucosa and lateral lip elements (some rely on muscle action to create a labial sulcus and do not formally reconstruct the sulcus).

• Hard palate repair varies widely and includes:

• complete closure with a vomer flap on both sides;

• complete closure on one side with a full vomer flap and partial repair of the opposite side with a vomer flap raised up to the pre-vomerine suture;

• complete closure on one side only leaving the contralateral side open.

• Variation in hard palate repair exists because raising a full bilateral vomerine flap may compromise blood supply to the pre-maxilla, but raising the flap to the pre-vomerine suture and no further is thought to maintain the blood supply to the pre-maxilla. If only one side is repaired at the first surgery then the child is brought back after approximately 6 weeks to close the contralateral side with a vomer flap.

• The nose is repaired as previously described for unilateral patients except both sides of the nose are dissected and primary positioning of the alar cartilages is carried out to construct the nasal tip and columella.

Incomplete lip

• Principles are the same as for complete cases and a functional repair should always be carried out.

• It is also important to address the nose in incomplete cases as there is usually a lip/nose deformity.

Management of palate

Principles

• Functional palatal repair is important for speech and may be important for Eustachian tube function.

• Timing of palatal repair is controversial:

• early closure prior to 1 year has been shown to benefit speech;

• delayed hard palate closure has only shown consistently improved growth when delayed into adolescence, but this results in unacceptably poor speech.

• Common practice in UK is to close the soft palate in cleft lip and palate patients and the entire palate in isolated cleft palates between 6–9 months.

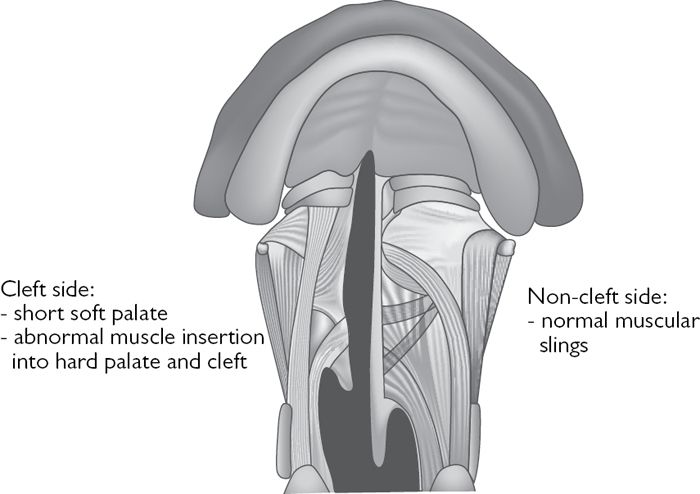

• Underlying deformity includes (Fig. 7.5):

• narrow and vertically displaced palatal shelves;

• abnormal insertion of palatal muscles;

• abnormal muscle in syndromic patients.

Fig. 7.5 Palatal muscles—normal vs cleft side.

Surgical options

• Hard palate in complete cleft lip and palate patients is repaired in the UK using a vomer flap (see ![]() Management of lip, p. 302 and Fig. 7.1).

Management of lip, p. 302 and Fig. 7.1).

• Many different techniques have been used to close the palate including:

• Von Langenbeck;

• Widmaier;

• Veau–Wardill–Kilner;

• Bardach two-flap technique with intravelar veloplasty;

• Furlow double opposing Z-plasty;

• Sommerlad radical micro-dissection.

• Von Langenbeck releasing incisions are still used in wide clefts.

• Veau–Wardill–Kilner push-back techniques still widely used in some countries, but abandoned in UK because of:

• unfavourable mid-facial growth;

• compromised dental arch form;

• difficult to manage fistulae;

• excessive palatal scarring;

• poor speech outcome.

• Sommerlad repair of the palate with microscopic magnification recreation of the levator veli palatini sling is widely practised in UK. Procedure involves:

• incision along cleft margin at junction of oral and nasal mucosa;

• mobilization of mucoperiosteum of hard palate in subperiosteal plane;

• separation of oral mucosa with minor salivary glands from muscles and nasal mucosa;

• division of oral insertion of tensor veli palatini tendon;

• suturing nasal layer with soft palate muscles still attached;

• separation of tensor veli palatini and palatopharyngeus from the back of the hard palate;

• dissection of levator veli palatini from the nasal mucosa keeping the nasal mucosa intact;

• alignment of the levators transversely and suture of the levators together in the midline to reconstitute the levator sling;

• closure of oral layer using resorbable sutures;

• lateral releasing incisions in the oral layer (Von Langenbeck) are used to reduce tension on the oral repair in <15% of cases (usually only) in extremely wide clefts;

• 5% of patients repaired using the Sommerlad technique have required secondary speech surgery.

• The Bardach double flap:

• widely practised in USA;

• hard palate is raised as two flaps subperiosteally giving access to soft palate musculature, which is repaired with an intravelar veloplasy;

• secondary speech surgery needed in >20% of patients.

• Furlow double-opposing Z-plasty:

• widely practised in USA;

• lengthens the palate and re-aligns levator veli palatini muscles;

• difficult in wide clefts;

• asymmetrical repair;

• normal or near normal speech reported in >85% of patients.

Management of alveolus

Aims of alveolar bone graft

• Stabilize alveolar arch.

• Restore arch integrity.

• Allow teeth to erupt into optimal position.

• Permit orthodontic alignment of arch.

• Simultaneous oronasal fistula repair.

• Creation of a platform for prosthetic replacement, e.g. implants.

• Optimize maxillary surgery.

• Create support for the nose (alar base) and lip.

Assessment

• OPT and occlusal radiograph.

• Periapical radiograph if necessary.

• CBCT scanning (becoming more popular).

• Important to decide whether tooth extractions need to be done. At the time or at least 3 months before to allow attached gingiva to heal.

• Pre-surgical orthodontic treatment to align alveolar segments and optimize position of teeth adjacent to the cleft.

Principles of surgery

• Pioneered by Boyne and Sands.

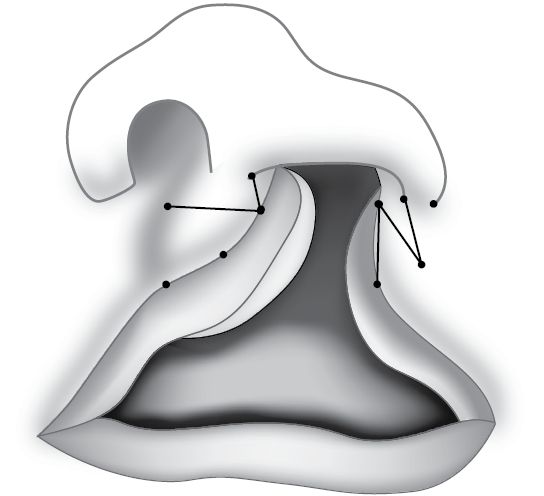

• Mucoperiosteal flaps are raised on both sides of the cleft on the buccal and palatal sides (Fig. 7.6).

• Reconstruction of nasal layer and create a nasal seal.

• Nasal dissection superiorly up to the piriform rim and nasal floor.

• Some place collagen membrane below the nasal layer to improve the nasal seal.

• Bone is packed into the space between the nasal layer and oral layer bridging the alveolar segments, and should extend posteriorly into the palatal cleft, superiorly to the nasal floor, and laterally to the paranasal region.

• Defect should be over-filled as resorption of up to 30% may occur.

• Oral closure is effected by advancing the lateral buccal mucoperiosteal flap medially to create an oral seal.

• Lateral buccal flap advancement will leave exposed alveolar bone laterally, which will heal by secondary intention without complication.

• Post-surgical orthodontics follows to provide stability, while bone graft is incorporated and heals.

Fig. 7.6 Alveolar bone graft—flaps raised and nasal layer closed.

Outcome assessment of alveolar bone

Outcome assessment of grafting is based on:

• Success of fistula closure.

• Eruption of canine and bony support for adjacent teeth.

• Objective radiographic measurement using panoramic and occlusal radiographs to assess bone height, and more recently conventional or CBCT to assess bone height and width.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses