and Jasdeep Kaur1

(1)

Earth and Life Sciences Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and ILEWG, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

7.1 Introduction

7.2 Definitions

7.12.3 Impressions

7.12.4 Removal of the Bite Mark

7.12.5 First Aid

7.13.1 History and Dental Records

7.13.2 Photographs

7.13.4 Impressions and Study Casts

7.13.5 Test Bites

7.13.6 DNA Samples

7.15 JBR Classification

7.18 Conclusions

Abstract

Bite marks are a vital and sometimes controversial aspect of forensic odontology. This chapter reviews the recognition and recovery of this evidence and provides insight into modern methods used to investigate bite mark evidence and its analysis from crimes.

7.1 Introduction

Bite mark analysis is a vital area within this highly specialized field and constitutes the commonest form of dental evidence presented in criminal court. It is well known that assailants in sexual attacks, including sexual homicide, rape, and child sexual abuse, often bite their victims as an expression of dominance, rage, and animalistic behavior. The first formally reported case of dental identification was that of the 80-year-old English warrior John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, who fell in the battle of Castillon in 1453 (Swanson 1967). The earliest recorded criminal case involving bite mark analysis was an American case (State of Ohio v. Robinson) in 1870, where in an individual named Robinson was charged with the murder of his mistress. Though there appeared to be a match between bite marks on the victim’s arms and his teeth, Robinson was acquitted of the charge (Pierce 1996). In 1906, colliers was charged with breaking and entering into a store followed by stealing some goods. During the examination of the premises, a block of cheese was discovered from which a piece had been bitten out, leaving teeth marks. Bite mark analysis and comparison led to his conviction (Pierce 1996). The scientific basis of bite mark analysis is rooted in the principle of the uniqueness of the human dentition, the belief that no two humans have identical dentitions in regard to size, shape, and alignment of the teeth (Heras et al. 2005). This declared uniqueness is transferred and recorded in the injury produced by the teeth during biting. The main aim of the analysis of bite mark cases is to connect the biter to the teeth pattern present in an object or the skin and to find out whether it is in any way related to the crime or event. The human skin has the ability to register sufficient detail of the teeth of the biter; however, it is quite variable. A number of studies have shown that the physical nature of the skin causes distortion of the bite marks. Moreover, the process of healing and decomposition produces changes in the bite marks that are left in the skin of dead or living individuals. Tooth markings may also be found in inanimate objects that might be associated with the crime, such as foods like chocolates, vegetables, chewing gums, Styrofoam cups, and cigarette butts, and even on the steering wheel of a car (Aboshi et al. 1994).

7.2 Definitions

According to authors of this chapter, a bite mark is defined as a patterned injury on the skin or other surface caused by the biting surfaces of human or animal teeth with a minimum amount of force. The ABFO manual defines a bite mark as “(1) a physical alteration in a medium caused by the contact of teeth, and (2) a representative pattern left in an object or tissue by the dental structures of an animal or human” (Freeman et al. 2005).

7.3 Teeth Marks and Bite Marks

The teeth can also leave marks without the act of biting, as is seen when the skin or the objects contact the teeth instead of the biter intentionally closing his jaws. So the teeth marks are reflexive, as there is no intentional, active, or reflexive jaw movement. These teeth marks are different from the bite marks where the muscles of the jaws are active, causing the teeth to move into the bitten substrate, which can be skin or any other object (Sweet and Pretty 2001).

7.4 Class and Individual Characteristics (Sweet and Pretty 2001)

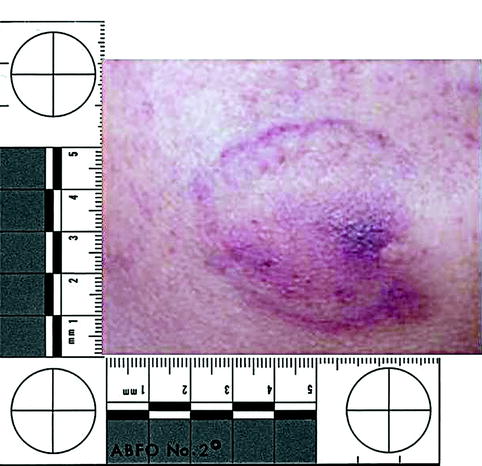

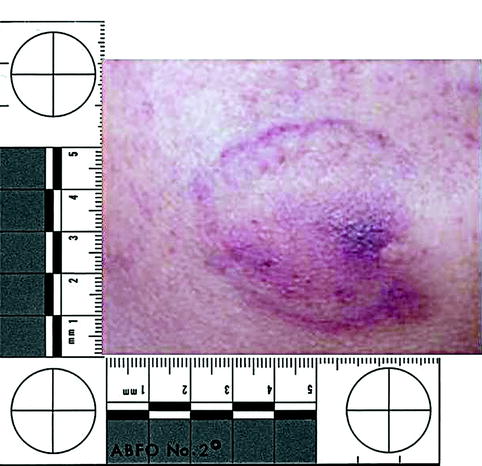

Human bite marks are mainly found on the skin of victims, and they may be found on almost all parts of the human body. Females are frequently bitten on the breasts and legs during sexual attacks, while bites on males are usually seen on the arms and shoulders (Pretty and Sweet 2000; Vale and Noguchi 1983). A typical representative human bite (Fig. 7.1) is depicted as an elliptical or circular injury that records the specific characteristics of the teeth (American Board of Forensic Odontology 1995). It may be composed of two U-shaped arches (Fig. 7.2) that are separated at their bases by an open space. The diameter of the injury typically ranges from 20 to 45 mm (Rai B 2011). Frequently, a central area of bruising can be seen within the bite marks from the teeth. In the center of the bite mark injury, due to the pressure created by the biting teeth and by the negative pressure created by the tongue and suction, there is extravascular bleeding, which causes bruising. The color of these bruises changes over a period of time and the color also changes as the injury undergoes a healing process in the skin of a living individual. The tooth class characteristics and bite mark characteristics are the two types of class characteristics. In a bite mark, the front teeth, which include the central incisors, lateral incisors, and cuspids, are the primary biting teeth according to tooth class characteristics. There are 12 teeth markings in a bite mark that has both the maxillary and mandibular front teeth. Each type of tooth in the human dentition has class characteristics that differentiate one tooth type from the others. The two mandibular central incisors and the two mandibular lateral incisors are almost uniform in width, while the mandibular cuspids are cone-shaped. When compared to the maxillary central incisors, the maxillary lateral incisors are narrower and the maxillary cuspids are cone-shaped. The upper jaw is wider than the lower jaw. The bite mark characteristics help us in determining which marks were made from the maxillary teeth and from the mandibular teeth. According to bite mark characteristics, the maxillary central incisors and lateral incisors make rectangular marks whose centrals are wider than the laterals, and the maxillary cuspids produce round or oval marks. The mandibular central incisors and lateral incisors also produce rectangular marks, but these are almost equal in width, whereas the mandibular cuspids produce round or oval marks. Sometimes the suspect may have a missing tooth/teeth, or due to breakage the tooth is shorter in size, or there may have been some clothing that prevented the tooth/teeth from contacting the skin. All these factors may lead to gaps that can be seen between the marks. Large carnivore or other animal bite marks such as dog bite wounds can be remarkable in their depth and amount of damage to the skin and underlying muscle. Use, misuse, and abuse of the teeth lead in exclusive features such as fractures, rotations, attritional wear, and congenital malformations, which are referred to as accidental or individual traits. When these are recorded in the injury, it may be possible to compare them to identify the specific teeth that caused the injury. These animals have extremely long canines and a complement of six incisors, plus the two canines, for a total of eight.

Fig. 7.1

Human bite marks

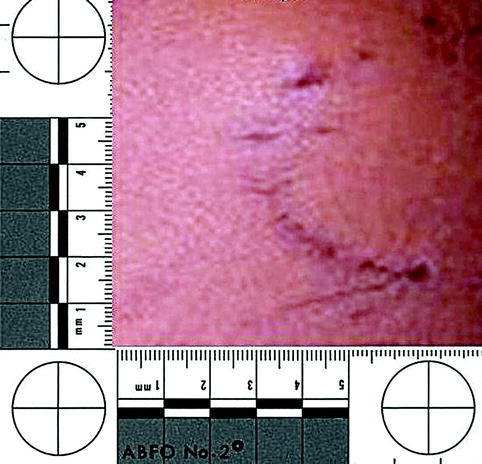

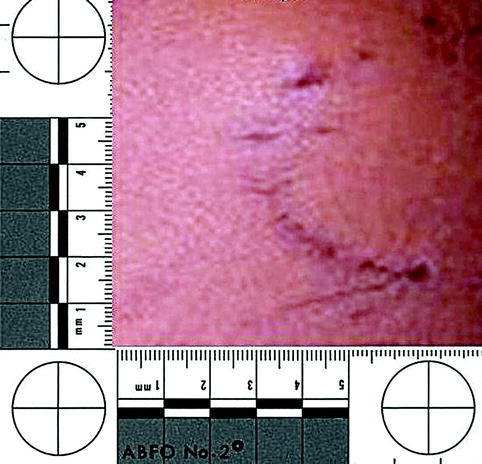

Fig. 7.2

U-shaped arches (human bite marks)

Note: The authors have witnessed blunt punch injuries that have resembled bite marks. These could be differentiated by the absence of class characteristics caused by human teeth in each case.

7.5 Additional Features (Bowers 2004)

Bite marks can have the following additional features:

1.

Ecchymosis:

(a)

Central ecchymosis: The negative pressure formed by the tongue and suction and the positive pressure created by closing of the teeth cause extravascular bleeding due to interruption of the small blood vessels, producing central ecchymosis.

(b)

Linear abrasions, contusions, or striations: These are produced by slipping of the teeth against the skin or by imprinting of the lingual surfaces of the teeth on the skin.

(c)

Double bite: It is also called bite within a bite and is produced when, during initial contact with the teeth, the skin slips and the teeth contact again for the second time with the skin.

(d)

Weave patterns of interposed clothing.

(e)

Peripheral ecchymosis: It is produced when there is excessive and confluent bruising.

2.

Partial bite marks:

(a)

One arched: Also called half-bites.

(b)

One or a few teeth.

(c)

Unilateral marks: They are produced when the dentition is incomplete or when there is irregular pressure during biting.

3.

Faded bite marks:

(a)

Fused arches: In this there are no individual tooth marks.

(b)

Solid: It is produced when the erythema or the contusion fills the entire central area of the bite mark. In this the bite mark does not show a ring pattern, but instead there is a discolored circular mark.

(c)

Closed arches: In this the maxillary and the mandibular arches are joined at their edges.

(d)

Latent: Seen with special imaging techniques.

4.

Superimposed bites: Two bite marks superimpose each other.

5.

Avulsive bites: In these the tissue is bitten off the victim during biting.

7.6 Locations of Bite Marks on Humans (Bowers 2004)

In case of sexual assault, females show evidence of bite marks on breasts, nipples, abdomen, thighs, and pubis, while males show bite marks mainly on the back, shoulders, and penis. In case of self-defense, individuals being attacked can receive bite marks from their attacker on their forearms and hands. Initial animal attacks on humans focus on the legs and then advance to hands, arms, and the head and neck. On female victims of violence, these sites include the breasts, thighs, abdomen, pubis, and buttocks, while defensive wounds on the hands and forearms of a victim must also be considered an option.

7.7 Multiple Biting Episodes

Bruises of differing colors can point out a series of separate biting actions. Disappearance of skin injuries may be difficult to see without close examination under various types of light, such as ultraviolet, alternative, and infrared lights (as described in Chap. 14).

7.8 Estimating the Age of Bite Marks

Bruises in the skin of humans change color as healing takes place. These color changes are different from person to person. Age estimation of bite marks is neither a scientific nor an accurate process. Ageing of bruises and bite marks can be used by changing in colour (Table 7.1) and can be detected using by different photography (Table 7.2).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses