Oral mucosal lesions are commonly encountered in clinical practice. One study reported that they occurred in approximately 27.9% of patients aged 17 years and older and in 10.3% of children aged 2 to 17 years. The diagnosis and treatment of mucosal diseases should be an integral part of the general practitioner’s practice. According to an American Dental Association survey conducted in 2007, 44% of biopsies were performed by a general practictioner. Understanding of the fundamentals of diagnosing mucocutaneous lesions requires a sound knowledge of their origin and clinical course, and of biopsy methods using contemporary diagnostic tools and techniques.

Oral mucosal lesions are commonly encountered in clinical practice. A study conducted in the United States reported that they occurred in approximately 27.9% of patients aged 17 years and older and in 10.3% of children aged 2 to 17 years. The diagnosis and treatment of mucosal diseases should be an integral part of the general practitioner’s practice. According to an American Dental (ADA) survey conducted in 2007, of 315,210 biopsies, 138,810 (44%) were performed by a general practictioner. Understanding of the fundamentals of diagnosing mucocutaneous lesions requires a sound knowledge of its origin and clinical course, and of biopsy methods using contemporary diagnostic tools and techniques.

Approach to lesions

A through systematic approach should be sought for every oral lesion, with the chief complaint as the starting point of the investigation.

Health History

A complete medical history should be obtained for all patients before performing an examination. An existing systemic condition can contribute to the cause of the lesion. For instance, does the patient have lupus erythematosus, a sexually transmitted disease, tuberculosis, or an immune-compromised condition [eg, HIV, AIDS, leukemia], is the patient currently undergoing chemotherapy treatment, or has the patient been prescribed any new medications by another provider that may be causing a lichenoid reaction. Social history is particularly important if the patient has a smoking, alcohol, or beetle quid habit, because these are well-known carcinogens.

Lesion History

The focus of the examination should then shift to the history of the lesion. The usual initial questions are how long has the lesion been present, was it noticed by the patient or during a routine oral screening, has the lesion changed in size, and is any associated paresthesia present. A benign lesion usually has a slower growth as opposed to one that is malignant, which is more aggressive and has associated paresthesia. Patients should be asked if any associated symptoms are present, such as pain, fever, headaches, chills, or lymphadenopathy, and whether the characteristics of the lesion changed (eg, did the ulcer start as crops of vesicles or was it always an ulcer). A change in its features would highly suggest vesiculobullous disease or a disease of viral origin. Furthermore, did any recent memorable events lead up to discovery of the lesion (eg, trauma, local irritant, exposure to allergens). For instance, if the lesion was caused by a sharp cup rubbing against the tongue, it would be best remedied by smoothing the offending origin, with an appropriate follow-up to determine if the lesion needs further investigation.

Clinical Examination

An understanding of the normal anatomy will help the general practitioner differentiate between normal mucosa and an oral lesion. The general practitioner should be able to describe the presentation of the lesion in terms of location, size, shape, growth pattern, the sharpness of lesion borders, mobility, and consistency of the lesion on palpation. The general practitioner must also be aware of the possibility of two or more different lesions or one lesion with different presentation. A head and neck examination with lymph node inspection is mandatory before any oral biopsy. Lymphadenopathy can result from the surgical biopsy itself and can be confusing if TMN cancer staging were deemed necessary in the future.

With the information gathered during the history and physical examination, the general practitioner can develop a working differential diagnosis. Developing a differential diagnosis helps the general practitioner in using certain biopsy techniques and diagnostic tools that can facilitate a correct diagnosis. This article addresses mucocutaneous lesions that will be encountered in the dental practice.

Mucocutaneous diseases

Primary Herpetic Gingivostomatitis and Recurrent Herpes Lesions (Labialis or Stomatitis)

Two strains of herpes simplex viruses (HSV) exist. HSV-1 is usually responsible for perioral/orofacial infections and HSV-2 for genital infections. Two clinical manifestations of HSV-1 can occur: primary herpetic gingivostomatitis and recurrent herpetic-lesion labialis (lips) or stomatitis (intraoral). The route of transmission is through infected saliva, active perioral lesions, and sores on skin. Transmission easily occurs through intimate contact, kissing, sharing eating utensils, and toothbrushes. Only 1% of the population that gets the primary infection develops full-blown symptoms. This condition is called primary herpetic gingivostomatitis . The other 60% to 90% of children and young adults seroconvert to HSV antibodies without any clinical symptoms. After a period of incubation (usually 7 days), patients can experience a variety of symptoms, including headaches, irritability, muscle soreness (myalgia), pain on swallowing, fever, and painful lymphadenopathy. Crops of vesicles appear and rupture within 24 hours and then coalesce to form ulcers in the oral mucosa involving the gingiva (keratinized and nonkeratinized), tongue, and lips ( Fig. 1 ). New lesions can continue to develop up to 7 more days and usually heal without scarring within 3 weeks.

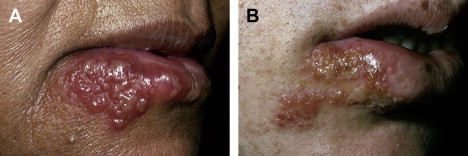

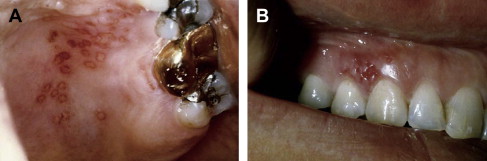

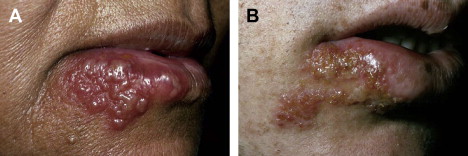

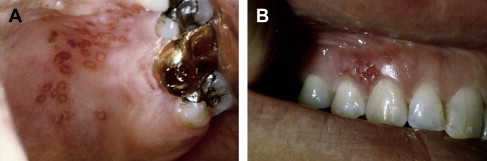

After the primary HSV infection, the virus lays dormant in a regional nerve ganglion (ie, trigeminal ganglion) until a stimulus triggers it to cause a secondary or recurrent infection. This stimulus may be sunlight (sun sores), physical or emotional stress, hormonal changes (menstrual cycle), preceding upper respiratory infection (fever blister or cold sores), or suppression of the immune system (caused by HIV, AIDS, or current chemotherapy). The two clinical manifestations include the labialis and stomatitis. Herpes labialis is the more common of the two recurrent HSV infections. The clinical course starts with a tingling or itching sensation (prodrome phase) after which these crops of vesicles will coalesce and rupture within 48 hours. It proceeds to ulcerate, leaving behind a crusted brownish lesion on the lip ( Fig. 2 ). The intraoral component (stomatitis) appears on keratinized gingiva (ie, hard palate or attached gingiva) and the tongue. The commonest region is the posterior hard palate over the greater palatine foramen ( Fig. 3 ). Unlike herpes labialis, these intraoral herpes seldom form vesicles, and proceed to ulcerate, leaving behind an erythematous macular base. Both clinical forms heal without scarring within 7 to 10 days.

Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis

Recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS) affects 20% of the population worldwide between ages 10 and 30 years, with 50% being college students. It occurs more common in women than men. The clinical signs and symptoms can include a tingling or burning sensation, a well-delineated white ulcer with erythematous halo, and the absence of a vesicular stage. Although the cause of RAS is still unknown, local and systemic predisposing factors can contribute to its development. Local injuries to the oral mucosa, such as from trauma or tobacco smoke, can be offending agents. Systemic diseases, such as Behçet’s disease, MAGIC (mouth and genital ulcers with inflamed cartilage) syndrome, PFAPA (periodic fever, aphthous-stomatitis, pharyngitis, adenitis) syndrome, cyclic neutropenia, HIV disease, and hematologic deficiencies (eg, iron, folic acid, vitamin B 12 ), could produce aphthous-like ulcerations in the oral cavity.

Three forms of RAS exist: (1) minor (canker sore), (2) major (Sutton disease, periadenitis mucosa necrotica recurrens), and (3) herpetiform ulcerations.

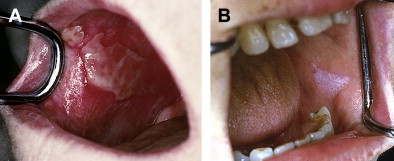

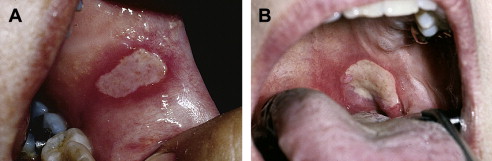

The minor form (canker sore) is the most common form of RASs, accounting for 80% of patients. Typically, these lesions are less than 5 mm in diameter, round, or oval-shaped with a grayish-white pseudomembrane and an erythematous halo. They appear on nonkeratinized surfaces on labial and buccal mucosa, the floor of the mouth, movable gingiva, the palate, and the dorsum of tongue ( Fig. 4 ). The lesions heal in 10 to 14 days uneventfully.

The major form affects 10% of the patients with RAS. The lesions are greater than 1.0 cm in diameter. They tend to locate on the lips, soft palate, and fauces ( Fig. 5 ). They last longer than the minor form and heal without scarring in 6 weeks. Major RAS has its onset after puberty and can persist for 20 years or more.

Herpetiform ulcerations present in 1% to 10% of patients with RAS. The lesions are usually 2 to 3 mm in diameter, with 100 ulcers appearing at a time. They can congregate into large lesions or diffuse throughout the oral cavity ( Fig. 6 ).

Lichen Planus

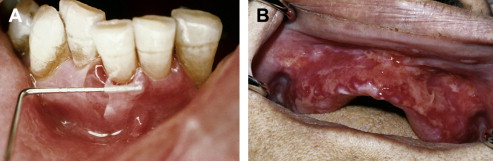

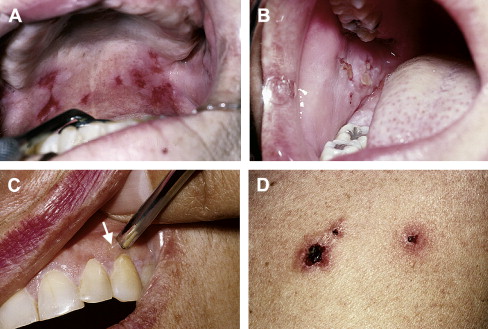

Lichen planus (LP) is a chronic mucocutaneous disease of unknown origin. It generally develops in patients between 40 and 70 years old, with a predilection for women (2:1). It affects the oral mucosa, tongue, and skin. The skin lesions occur on the flexor surface of the extremities with the four Ps (purple, pruritic, polygonal papules) ( Fig. 7 ). Although oral LP is prevalent in 2% of the population, skin lesions show along side with oral lesions in 12% to 14% of the time. Oral LP can be classified into two types: reticular (reticular, plaque-like) and erosive (atrophic, bullous, ulcerative) ( Fig. 8 ). Reticular LP is much more common than the erosive form, with a higher predilection for buccal mucosa (bilateral 85% of the time), the dorsum surface of tongue, and attached gingiva. The reticular form is asymptomatic. It gets its name because of the interlacing white lines patterns known as Wickham striae ( Fig. 9 ). These lesions wax and wane over weeks and months. However, the erosive type can have a long painful clinical course. Clinically, atrophic and erythematous areas are present, with central ulceration of varying degrees. The periphery is usually bordered by fine, white, radiating striae. Sometimes the atrophy and ulceration are confined to the gingival mucosa, called desquamative gingivitis . If the erosive component is severe, epithelial separation from the underlying connective tissue may occur, followed by minor trauma. This rare presentation is known as bullous lichen planus . Controversy exists over the actual malignant transformation of erosive LP to squamous cell carcinoma (1.5%–2.5%).

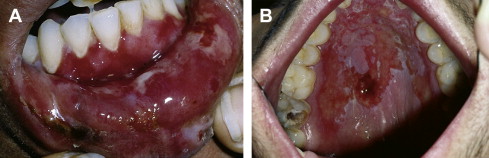

Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid

Mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP) is an autoimmune disease that affects many mucosal surfaces, including oral, ocular, nasal, esophageal, laryngeal, pharyngeal, genital, and skin. Oral and ocular surfaces remain the most common sites. The mean age of onset is older than 40 years, with predilection for women (2:1). Oral manifestations include vesiculobullous eruptions, desquamative gingivitis, and ulcerations ( Fig. 10 ). With gingiva being the most common site, these lesions begin as painful fluid-filled blisters that then slough off, leaving behind a denuded ulcerative base ( Fig. 11 ). Epithelial sloughing with digital pressure or perilesional manipulation indicates a positive Nikolsky sign, and resembles the skin falling off of a sour grape. Healing may take days to weeks, and scarring is usually not seen. The ocular component can progress to scarring, resulting in fusion of the eyelid and conjunctiva (symblepharon) (11%–61%). Poorly treated or untreated ocular lesions can ultimately lead to blindness. Lesions on the laryngeal mucosa can also lead to severe scarring, resulting in stricture. Skin involvement is only a small component and is manifested in 0% to 11% of cases. A proper referral to the ophthalmology; otolaryngology; urology; or dermatology department is necessary for proper care.

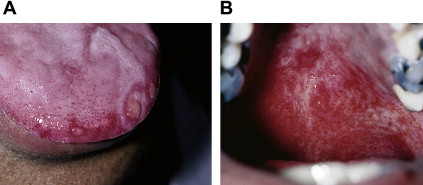

Pemphigus Vulgaris

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is an autoimmune disease involving the skin and mucous membrane that can be life-threatening. It affects a wide age range, from children to adults, with a predilection for people in their fourth to sixth decade. The condition is seen more often in individuals of Ashkenazi Jewish or Mediterranean descent. The overall incident is 0.1 to 0.5 patients per 100,000 population per year.

The oral component of PV begins as a bulla formation, which will quickly rupture and leave behind a painful ulcerative base. The oral cavity is commonly the first site for PV development and can be found in the buccal mucosa, palatal mucosa, and lips ( Fig. 12 ). Lesions confined in the oral cavity are not life-threatening, whereas cutaneous involvement is considerably more severe and fatal. Death is caused by septicemia or a fluid and electrolyte imbalance. Other mucous membranes may be affected, including the conjunctiva, nasal mucosa, pharynx, larynx, esophagus, and genital mucosa. Referral to a specialist is necessary for appropriate treatment. The clinical course has a rapid onset with a variable and unpredictable resolution.

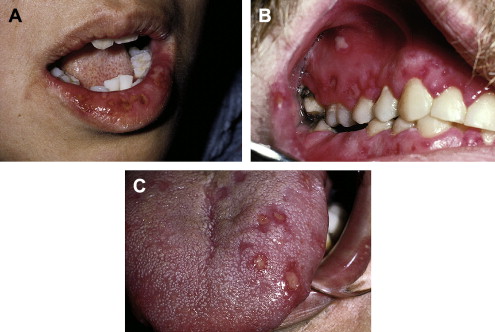

Erythema Multiforme

Erythema multiforme (EM) is an acute immune-based inflammatory disease that affect both mucous membrane and skin (target lesion). The mucosal lesions include ocular, oral, and genital surfaces. EM seems to be a disease of children and young adults between 20 and 30 years of age. The origin is thought to be triggered by precipitating factors, such as infection, drugs, gastrointestinal conditions, malignancies, radiation therapy, or vaccination, with an explosive onset.

EM has two clinical forms, EM minor and EM major. EM minor more often affects the skin than the oral cavity (25%). The minor form can affect no more than one mucosal surface, with skin involvement. The minor form has a prodrome phase characterized by symptoms such as headache, fever, and malaise, followed by the formation of a papule or bulla that collapses to form “target lesions” ( Fig. 13 ). The oral presentation of EM minor has the same characteristics, ranging from similar to aphthous-like ulcers to diffused erythematous erosion spots. The condition is self-limiting, with resolution in 2 to 3 weeks. A correlation of oral and cutaneous findings is needed to make the diagnosis. Tissue biopsy is not necessary to rule out this lesion; however, ruling out other vesiculobullous diseases may be helpful.

EM major is characterized by involvement of two or more mucosal surfaces and skin surfaces. The bulla develops and later pops, leaving a dark-red crusted lesion. EM major has two forms: (1) Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), or Lyell syndrome. The Stevens-Johnson syndrome is characterized by an extensive oral lesion commonly found in keratinized and nonkeratinized gingiva and bloody crusted lips ( Figs. 14 and 15 ). Extraoral involvement includes ocular, esophageal, and genital surfaces. Scarring and partial blindness can result from ocular involvement. The mortality rate is 5% for Stevens-Johnsons syndrome. TEN is an even more extreme form of EM major, with a mortality rate as high as 30% to 35%. The skin lesions are extensive and can resemble severe burns. Death occurs because of substantial loss of electrolytes and fluids, and widespread infection.

Lupus Erythematosus

Lupus erythematosus is a chronic inflammatory disease that targets the oral and cutaneous surfaces, and the end organs associated with circulating autoantibodies. Its origin is not fully understood, but it is thought to be caused by environmental, genetic, and hormonal factors. Three forms of lupus erythematosus exist: (1) discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), (2) subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), and (3) systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). DLE is the mildest form and is confined to the cutaneous surface of the face; the scalp, with associated hair loss (alopecia); the ears, and occasionally the oral mucosa. The intermediate form is SCLE, which affects the head and neck and upper trunk, and extensor surfaces of the arm. Myalgia, arthralgia, fatigue, and malaise are common symptoms. The most severe and commonest form is SLE. These circulating autoantibodies target end organs, resulting in inflammation to the heart (pericarditis), lungs (pleurisy or pleural effusion), kidneys (lupus nephritis), and vasculature (vasculitis). Bone marrow with an anemia profile is present. The classic “butterfly rash” is found across the malar region ( Fig. 16 ). The disease affects primarily women (9:1) during childbearing years, with an oral manifestation around 21%.

The oral manifestation of lupus can have a variety of appearances, ranging from leukoplakia, to erythematous erosions, to chronic ulcerations. The leukoplakia lesions can be longstanding in the oral cavity without any symptoms. Patients will complain of burning mouth symptoms associated with the erythema and ulcerative conditions ( Fig. 17 ).

Mucocutaneous diseases

Primary Herpetic Gingivostomatitis and Recurrent Herpes Lesions (Labialis or Stomatitis)

Two strains of herpes simplex viruses (HSV) exist. HSV-1 is usually responsible for perioral/orofacial infections and HSV-2 for genital infections. Two clinical manifestations of HSV-1 can occur: primary herpetic gingivostomatitis and recurrent herpetic-lesion labialis (lips) or stomatitis (intraoral). The route of transmission is through infected saliva, active perioral lesions, and sores on skin. Transmission easily occurs through intimate contact, kissing, sharing eating utensils, and toothbrushes. Only 1% of the population that gets the primary infection develops full-blown symptoms. This condition is called primary herpetic gingivostomatitis . The other 60% to 90% of children and young adults seroconvert to HSV antibodies without any clinical symptoms. After a period of incubation (usually 7 days), patients can experience a variety of symptoms, including headaches, irritability, muscle soreness (myalgia), pain on swallowing, fever, and painful lymphadenopathy. Crops of vesicles appear and rupture within 24 hours and then coalesce to form ulcers in the oral mucosa involving the gingiva (keratinized and nonkeratinized), tongue, and lips ( Fig. 1 ). New lesions can continue to develop up to 7 more days and usually heal without scarring within 3 weeks.

After the primary HSV infection, the virus lays dormant in a regional nerve ganglion (ie, trigeminal ganglion) until a stimulus triggers it to cause a secondary or recurrent infection. This stimulus may be sunlight (sun sores), physical or emotional stress, hormonal changes (menstrual cycle), preceding upper respiratory infection (fever blister or cold sores), or suppression of the immune system (caused by HIV, AIDS, or current chemotherapy). The two clinical manifestations include the labialis and stomatitis. Herpes labialis is the more common of the two recurrent HSV infections. The clinical course starts with a tingling or itching sensation (prodrome phase) after which these crops of vesicles will coalesce and rupture within 48 hours. It proceeds to ulcerate, leaving behind a crusted brownish lesion on the lip ( Fig. 2 ). The intraoral component (stomatitis) appears on keratinized gingiva (ie, hard palate or attached gingiva) and the tongue. The commonest region is the posterior hard palate over the greater palatine foramen ( Fig. 3 ). Unlike herpes labialis, these intraoral herpes seldom form vesicles, and proceed to ulcerate, leaving behind an erythematous macular base. Both clinical forms heal without scarring within 7 to 10 days.

Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis

Recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS) affects 20% of the population worldwide between ages 10 and 30 years, with 50% being college students. It occurs more common in women than men. The clinical signs and symptoms can include a tingling or burning sensation, a well-delineated white ulcer with erythematous halo, and the absence of a vesicular stage. Although the cause of RAS is still unknown, local and systemic predisposing factors can contribute to its development. Local injuries to the oral mucosa, such as from trauma or tobacco smoke, can be offending agents. Systemic diseases, such as Behçet’s disease, MAGIC (mouth and genital ulcers with inflamed cartilage) syndrome, PFAPA (periodic fever, aphthous-stomatitis, pharyngitis, adenitis) syndrome, cyclic neutropenia, HIV disease, and hematologic deficiencies (eg, iron, folic acid, vitamin B 12 ), could produce aphthous-like ulcerations in the oral cavity.

Three forms of RAS exist: (1) minor (canker sore), (2) major (Sutton disease, periadenitis mucosa necrotica recurrens), and (3) herpetiform ulcerations.

The minor form (canker sore) is the most common form of RASs, accounting for 80% of patients. Typically, these lesions are less than 5 mm in diameter, round, or oval-shaped with a grayish-white pseudomembrane and an erythematous halo. They appear on nonkeratinized surfaces on labial and buccal mucosa, the floor of the mouth, movable gingiva, the palate, and the dorsum of tongue ( Fig. 4 ). The lesions heal in 10 to 14 days uneventfully.

The major form affects 10% of the patients with RAS. The lesions are greater than 1.0 cm in diameter. They tend to locate on the lips, soft palate, and fauces ( Fig. 5 ). They last longer than the minor form and heal without scarring in 6 weeks. Major RAS has its onset after puberty and can persist for 20 years or more.

Herpetiform ulcerations present in 1% to 10% of patients with RAS. The lesions are usually 2 to 3 mm in diameter, with 100 ulcers appearing at a time. They can congregate into large lesions or diffuse throughout the oral cavity ( Fig. 6 ).

Lichen Planus

Lichen planus (LP) is a chronic mucocutaneous disease of unknown origin. It generally develops in patients between 40 and 70 years old, with a predilection for women (2:1). It affects the oral mucosa, tongue, and skin. The skin lesions occur on the flexor surface of the extremities with the four Ps (purple, pruritic, polygonal papules) ( Fig. 7 ). Although oral LP is prevalent in 2% of the population, skin lesions show along side with oral lesions in 12% to 14% of the time. Oral LP can be classified into two types: reticular (reticular, plaque-like) and erosive (atrophic, bullous, ulcerative) ( Fig. 8 ). Reticular LP is much more common than the erosive form, with a higher predilection for buccal mucosa (bilateral 85% of the time), the dorsum surface of tongue, and attached gingiva. The reticular form is asymptomatic. It gets its name because of the interlacing white lines patterns known as Wickham striae ( Fig. 9 ). These lesions wax and wane over weeks and months. However, the erosive type can have a long painful clinical course. Clinically, atrophic and erythematous areas are present, with central ulceration of varying degrees. The periphery is usually bordered by fine, white, radiating striae. Sometimes the atrophy and ulceration are confined to the gingival mucosa, called desquamative gingivitis . If the erosive component is severe, epithelial separation from the underlying connective tissue may occur, followed by minor trauma. This rare presentation is known as bullous lichen planus . Controversy exists over the actual malignant transformation of erosive LP to squamous cell carcinoma (1.5%–2.5%).