This case report describes a Class I crowded malocclusion with an ankylosed maxillary central incisor that was in infraocclusion and labially displaced. The patient had wide maxillary teeth, and the option of extracting the maxillary central incisors followed by space closure, with lateral incisors substituting for the central incisors, was chosen.

Ankylosed permanent maxillary central incisors in a growing patient are a clinical challenge for any orthodontist. Ankylosis results from the fusion of a portion of the cementum of the root to the adjacent alveolar bone. Permanent ankylosis frequently occurs after trauma, especially intrusive luxation. This means that the tooth becomes an integral part of the bone remodeling system, and, whereas the neighboring teeth erupt normally with alveolar growth, the ankylosed incisor does not erupt and eventually is in infraocclusion with a higher gingival margin and is often displaced labially.

In these cases, extraction of the ankylosed tooth and space closure might be a solution. Decisions about the direction of treatment usually are based on several factors: type of malocclusion, space conditions, lateral incisor width and root length, and shape and shade of the canines. From an orthodontic perspective, absence of maxillary anterior teeth can provide the space and opportunity to alleviate a crowded dentition or an enlarged horizontal overlap without extracting other teeth. However, this approach requires the lateral incisors to assume the functional and esthetic role of central incisors; the canines become the lateral incisors, and the first premolars take the role of the canines, with all the prosthetic camouflage that these positional changes require. Therefore, the objective of this article was to demonstrate this situation with a clinical patient and discuss the advantages and disadvantages of this approach.

Diagnosis and etiology

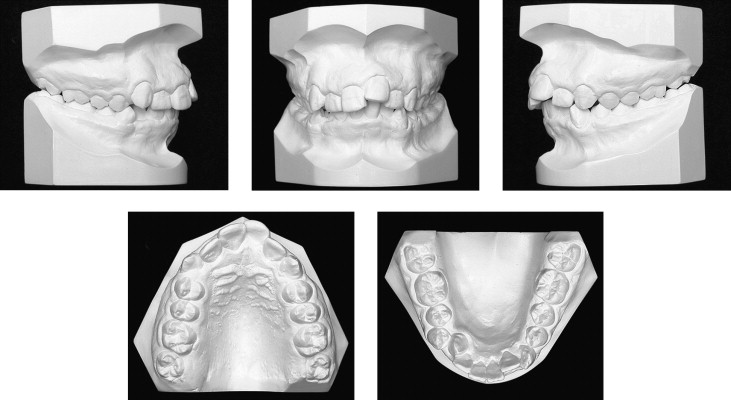

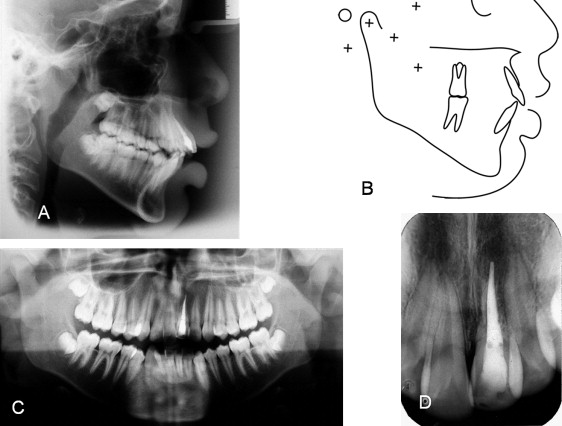

A boy, aged 13 years 11 months, was brought to the Department of Orthodontics at Bauru Dental School, University of São Paulo in Brazil, for evaluation. His chief complaint was impaired esthetics because of crowding. He had moderate dental irregularity and a Class I biprotrusive malocclusion ( Figs 1-3 ). The left maxillary central incisor was ankylosed, with a higher gingival level than the adjacent teeth. He had a traumatic episode at age 11 years, and the maxillary left central incisor was avulsed. The tooth received endodontic treatment and was reimplanted. The periapical radiograph shows the endodontic treatment and the root resorption of the ankylosed maxillary left central incisor ( Fig 3 , D ). His face was symmetric, but there was no passive lip competence at rest.

Treatment objectives

The primary objectives were to eliminate the patient’s crowding and excessive lip protrusion and to improve his facial appearance. The maxillary anterior gingival margins would need to be leveled, and the maxillary left central incisor ankylosis and root resorption would need to be addressed, to establish acceptable anterior dental esthetics.

Treatment objectives

The primary objectives were to eliminate the patient’s crowding and excessive lip protrusion and to improve his facial appearance. The maxillary anterior gingival margins would need to be leveled, and the maxillary left central incisor ankylosis and root resorption would need to be addressed, to establish acceptable anterior dental esthetics.

Treatment alternatives

Based on the objectives, 3 treatment options were proposed. The first option consisted of extracting the 4 first premolars to relieve the crowding and dentoalveolar protrusion followed by extraction of the ankylosed central incisor. A single-tooth implant would be considered as a prosthetic option to replace the extracted incisor after facial growth. A disadvantage of this option was that it would commit this young patient to a permanent prosthesis in an area of the mouth in which tooth shade, gingival contour, and margins are critical and not always easy to control. The second option consisted of extracting the ankylosed central incisor, the maxillary right first premolar, and the mandibular first premolars. The left lateral incisor would be moved into the central incisor extraction site. A composite buildup would transform the lateral into a central incisor. But the anterior dental esthetic result would be a problem. When a maxillary lateral incisor replaces a missing central incisor, the problem is to duplicate the shape of the contralateral central incisor. It is difficult to create an ideal crown shape because of the reduced clinical crown height of the lateral incisor. In addition, the mesial and distal surfaces of the crown must be overcontoured, because of the narrower cervical region of the lateral incisor. The third option consisted of extracting both maxillary central incisors and the mandibular first premolars. This option seemed to be the most plausible, because the lateral incisors were unusually large mesiodistally, and they could easily be contoured as central incisors. The lateral incisors would be moved into the central incisor position, and composite buildup would transform the lateral incisors into central incisors. The patient and his parents preferred this option, because fewer teeth would be extracted, and the overall esthetics would be easier to manage.

Treatment progress

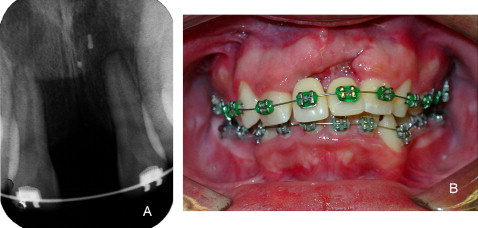

After completing the initial preorthodontic procedures, extraction of the maxillary central incisors and mandibular first premolars was requested. When the ankylosed central incisor was extracted, the labial bone was lost as expected, and a significant vertical and buccolingual defect appeared ( Fig 4 ). The first molars were banded, and preadjusted 0.022 × 0.028-in brackets were placed on all remaining teeth. Prosthetic maxillary central incisors were fixed to the archwire at the extractions sites ( Fig 5 ).

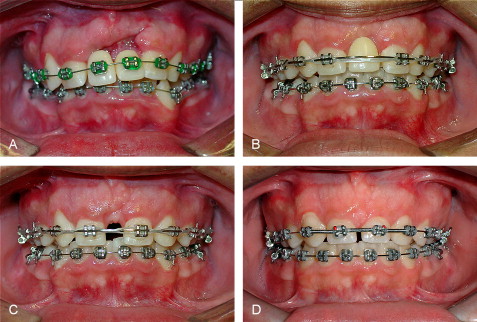

The artificial teeth were gradually reduced proximally, and both arches were leveled and aligned orthodontically. At the end of the alignment phase, the narrow prosthetic teeth were replaced by 1 artificial tooth fixed on a palatal plate, which was removed later to facilitate space closure ( Fig 5 ). Space closure was accomplished with rectangular 0.019 × 0.025-in stainless steel archwires and intramaxillary elastic chains. The anterior extraction spaces were partially closed, leaving well-distributed interproximal spaces to be filled by composite restoration of the maxillary lateral incisors. The bone defect was filled progressively, while the lateral incisors were moved into the central incisor extraction sites.

At the end of orthodontic treatment, gingivectomy and direct composite buildup of the maxillary lateral incisors and canines transformed them into central and lateral incisors, respectively.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses