The microbiology of head and neck infections is constantly changing. This continual dynamic evolution of the microflora of oral and head and neck infections is due to rapid genetic change in the microorganisms that cause them. Oral bacteria can reproduce as frequently as every 20 minutes. This rapid genetic turnover affords pathogens the ability to respond quickly to environmental pressures, such as antiseptics and antibiotics. In addition, our understanding of the molecular biology of oral pathogens is progressing at an ever-increasing rate. As a result, the nomenclature of oral pathogens is constantly changing as well. All of these factors necessitate constant study of the microbiology and antimicrobial treatment of head and neck infections.

The rapid ability of bacteria to respond to antibiotic selection pressure enables them to adapt to the therapeutic milieu that we as health care providers establish. For example, increasing penicillin-resistance rates were noted among the oral flora in the decade of the 1990s. This prompted a change from penicillin to clindamycin as the empirical antibiotic of choice for orofacial infections. On the other hand, since 2000 the virtually indiscriminate use of clindamycin may have resulted in increasing numbers of clindamycin-resistant oral streptococci. These same organisms have remained generally penicillin-sensitive. Thus many clinicians believe that in the nonallergic patient, penicillin and amoxicillin have returned to the status of first empirical antibiotics of choice in the treatment of odontogenic infections.

As our experience with new and even older antibiotics continues to mount, we become aware of new complications and the mechanisms of previously recognized complications of antibiotic therapy. For example, antibiotic-associated colitis has now been associated with the exotoxin elaborated by Clostridium difficile. Once the cause of antibiotic-associated colitis was identified, we were able to establish diagnostic and treatment methods for this antibiotic complication. Among the fluoroquinolones, the propensity of moxifloxacin, for example, to prolong the cardiac Q-T interval has limited its usefulness and necessitated an increased awareness of the potential for drug interactions associated with antibiotic therapy. The fluoroquinolones, as a class of drugs, interfere with proper development of growing cartilage. Therefore they are not used in patients younger than 18 years.

Thus all of these considerations require oral and maxillofacial surgeons to remain constantly abreast of new developments in the microbiology and antibiotic therapy of head and neck infections.

Etiopathogenesis and Causative Factors

Most infections of the head and neck are initiated by streptococci and perpetuated by anaerobes. This pattern probably applies to nonodontogenic as well as odontogenic abscess-forming head and neck infections. The streptococci are able to elaborate hyaluronidases that lyse the ground substance of connective tissue, allowing the bacteria to spread through soft tissue planes. Then, these bacteria are able to synthesize nutrients upon which the anaerobic members of the infecting flora depend. Further, the streptococci are able to consume local oxygen supplies, and by their acidic by-products, reduce the pH of the infected site. In this manner, the invading streptococci are able to create a favorable environment for the later growth of obligate anaerobic bacteria. Thus, in the first 3 days of symptoms, a predominantly aerobic or facultative flora is cultivated from head and neck infections. Thereafter, a mixed flora of aerobic or facultative organisms plus anaerobes can be isolated. Once an infection matures and the local oxygen supplies have been consumed, such as within an abscess cavity, a purely anaerobic flora is often identified.

Many of the anaerobic bacteria, however, are able to synthesize penicillinases. This capability allows the anaerobic members of the infecting flora to “return the favor” to the invading species by neutralizing many β-lactam antibiotics, such as penicillin, providing protection for otherwise penicillin-sensitive organisms. This phenomenon has been demonstrated in a recent case series of severe odontogenic infections requiring hospitalization, in which penicillin therapy failed in 21% of patients receiving it and in 60% of the cases in which one or more penicillin-resistant organisms was isolated.

The usual pathogens of head and neck infections are listed in Table 116-1 . The similarities among the pathogens associated with the various types of head and neck infection lend further credence to the concept that the primary pathogenic agents of head and neck infections are streptococci plus anaerobes. One may add to that list certain respiratory pathogens, such as Haemophilus influenzae, and S taphylococcus aureus for skin-related or nosocomial infection, such as poststernotomy osteomyelitis of the sternum. Necrotizing fasciitis occurs in four types, according to the microbial etiology. In the head and neck, the polymicrobial and the streptococcal types occur most frequently.

| TYPE OF INFECTION | MICROORGANISMS | |

|---|---|---|

| Odontogenic cellulitis/abscess | Streptococcus milleri group | |

| Peptostreptococci | ||

| Prevotella and Porphyromonas | ||

| Fusobacteria | ||

| Rhinosinusitis | Acute | Streptococcus pneumoniae |

| Haemophilus influenzae | ||

| Head and neck anaerobes ( Peptostreptococcus, Prevotella, Porphyromonas, Fusobacterium ) | ||

| GABHS (group A beta-hemolytic streptococci) | ||

| Staphylococcus aureus | ||

| Moraxella catarrhalis | ||

| Viruses | ||

| Chronic | Head and neck anaerobes | |

| Fungal | Aspergillus | |

| Rhizopus spp. (Mucor) | ||

| Nosocomial (esp. if intubated) | Enterobacteriaceae (esp. Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter, Escheria coli ) | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | ||

| Yeasts ( Candida spp.) | ||

| Osteomyelitis of the jaws | Acute | Odontogenic flora |

| Staphylococcus aureus and skin flora in trauma | ||

| Salmonella in sickle cell disease | ||

| Chronic | Actinomyces spp. | |

| Necrotizing fasciitis | Streptococcal (Groups A, C, G) | |

| Polymicrobial (aerobes + anaerobes) | ||

| Clostridial | ||

| Community-associated MRSA | ||

| Fungal | Mucosal or disseminated | Candida spp. |

| Soft tissue | Histoplasma spp. | |

| Blastomyces sp. | ||

| Sinus | Aspergillus | |

| Rhizopus (Mucor) |

Some head and neck infections are caused by pathogens other than bacteria. Of course, there are viral infections such as herpes simplex stomatitis and herpangina. Fungal infections, such as mucormycosis and noma, may also occur in the immunosuppressed or malnourished patient. Mycobacterial infections are divided into tuberculous and nontuberculous types. Table 116-2 lists the comparative diagnostic features of tuberculous and nontuberculous infections of the head and neck. This information may assist the clinician in choosing diagnostic maneuvers for identifying mycobacterial infections.

| CLINICAL FEATURE | TUBERCULOUS | NONTUBERCULOUS |

|---|---|---|

| Cervical lymphadenitis | Posterior, supraclavicular, multiple, bilateral | Enlarging mass around the mandible |

| Constitutional symptoms (fever, weight loss, fatigue) | Present | Absent |

| History of tuberculosis or TB contact | Present | Absent |

| Sinus formation | High | Low |

| Age | Adult | Child |

| Tuberculin skin test (PPD) | Positive | Intermediate or negative |

| Chest x-ray | Signs of active or previous tuberculosis | Normal |

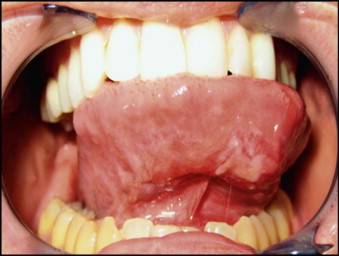

A new association between syphilis and HIV among men who have sex with men (MSM) may present as orofacial infection. There has been a dramatic increase in syphilis among MSM in the United States in recent years. This spread of syphilis has been facilitated by the misconception that unprotected oral sex is safe, since HIV is not carried in saliva at infective levels. On the other hand, the syphilitic chancre and the mucus patches of secondary syphilis are highly infective with Treponema pallidum. The ulcerated lesions of primary and secondary syphilis serve as very effective portals of entry for HIV. In this manner, syphilis may serve as a potentiating cofactor in the spread of HIV infection. An oral chancre is illustrated in Figure 116-1 .

Pathologic Anatomy

The usual pathogens of head and neck infections are the oral streptococci and anaerobes. Both of these groups are excellent abscess-formers, and when these organisms are introduced deeply into the tissues, such as in a dental periapical infection, the infection tends to pass through the stages of infection. These are inoculation, the spread of bacteria into soft tissue spaces; edema, the initial inflammatory response to bacteria and their by-products; cellulitis, a highly inflamed spreading induration; abscess, characterized by central fluctuance and suppuration; and finally resolution, when spontaneous or surgical drainage is achieved. Further, the infection tends to spread through recognized anatomic compartments, such as bone, fascial spaces, the paranasal sinuses, or vascular structures, especially the valveless head and neck veins. The anatomic presentation of various head and neck infections is presented later, in the chapter on the surgical therapy of head and neck infections.

Other types of head and neck infections, however, also follow characteristic anatomic patterns. For example, viruses and treponemes tend to cause spreading surface mucosal infections, such as herpes and syphilis. The superficial form of necrotizing fasciitis follows the platysma muscle from the inferior border of the mandible down the neck and onto the chest wall. This phenomenon is illustrated in Figure 116-2 , which depicts the end result of necrotizing fasciitis, osteomyelitis, and split-thickness skin grafting in a patient with uncontrolled HIV infection, multiple periapical abscesses, and osteomyelitis of the mandible.

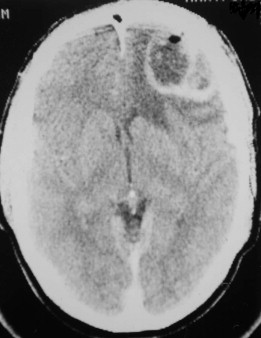

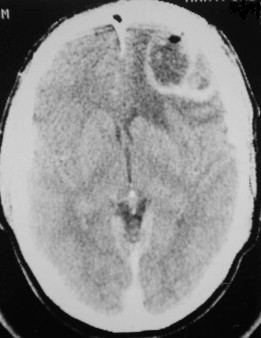

Fungal infections tend to follow microvascular patterns. Their propensity to invade and occlude capillaries and other small vascular channels causes the necrosis seen in mucormycosis and other related infections. On the other hand, bacterial infections may occasionally follow the larger vascular pathways. Odontogenic cavernous sinus thrombosis, as illustrated in Figure 116-3 , follows recognized venous pathways from the face into the cranium. Small emissary veins that perforate the inner table of the cranium may allow bacteria from chronic sinusitis to pass into the brain, causing brain abscess, as illustrated in Figure 116-4 . Sometimes these small emissary veins also allow infection to pass through paper-thin layers of bone from the sinuses into the orbit, as illustrated in Figure 116-5 , in which a maxillary and ethmoid sinusitis passed through the lamina papyracea into the orbit, causing orbital subperiosteal abscess.

Necrotizing fasciitis may also have a deep anatomic pattern. Cases historically described as descending necrotizing mediastinitis may represent the same process as necrotizing fasciitis, only on a deeper anatomic plane. Rapidly developing cases of mediastinitis, characterized by necrotic tissue found deep in the neck at surgical exploration, may simply be cases of necrotizing fasciitis that have followed the deep fascial planes of the neck into the danger space and from there into the mediastinum.

Pathologic Anatomy

The usual pathogens of head and neck infections are the oral streptococci and anaerobes. Both of these groups are excellent abscess-formers, and when these organisms are introduced deeply into the tissues, such as in a dental periapical infection, the infection tends to pass through the stages of infection. These are inoculation, the spread of bacteria into soft tissue spaces; edema, the initial inflammatory response to bacteria and their by-products; cellulitis, a highly inflamed spreading induration; abscess, characterized by central fluctuance and suppuration; and finally resolution, when spontaneous or surgical drainage is achieved. Further, the infection tends to spread through recognized anatomic compartments, such as bone, fascial spaces, the paranasal sinuses, or vascular structures, especially the valveless head and neck veins. The anatomic presentation of various head and neck infections is presented later, in the chapter on the surgical therapy of head and neck infections.

Other types of head and neck infections, however, also follow characteristic anatomic patterns. For example, viruses and treponemes tend to cause spreading surface mucosal infections, such as herpes and syphilis. The superficial form of necrotizing fasciitis follows the platysma muscle from the inferior border of the mandible down the neck and onto the chest wall. This phenomenon is illustrated in Figure 116-2 , which depicts the end result of necrotizing fasciitis, osteomyelitis, and split-thickness skin grafting in a patient with uncontrolled HIV infection, multiple periapical abscesses, and osteomyelitis of the mandible.

Fungal infections tend to follow microvascular patterns. Their propensity to invade and occlude capillaries and other small vascular channels causes the necrosis seen in mucormycosis and other related infections. On the other hand, bacterial infections may occasionally follow the larger vascular pathways. Odontogenic cavernous sinus thrombosis, as illustrated in Figure 116-3 , follows recognized venous pathways from the face into the cranium. Small emissary veins that perforate the inner table of the cranium may allow bacteria from chronic sinusitis to pass into the brain, causing brain abscess, as illustrated in Figure 116-4 . Sometimes these small emissary veins also allow infection to pass through paper-thin layers of bone from the sinuses into the orbit, as illustrated in Figure 116-5 , in which a maxillary and ethmoid sinusitis passed through the lamina papyracea into the orbit, causing orbital subperiosteal abscess.

Necrotizing fasciitis may also have a deep anatomic pattern. Cases historically described as descending necrotizing mediastinitis may represent the same process as necrotizing fasciitis, only on a deeper anatomic plane. Rapidly developing cases of mediastinitis, characterized by necrotic tissue found deep in the neck at surgical exploration, may simply be cases of necrotizing fasciitis that have followed the deep fascial planes of the neck into the danger space and from there into the mediastinum.

Diagnostic Studies

The Gram stain is a simple and rapidly available diagnostic test that can quickly identify broad categories of bacteria. This test indicates the ability of the sampled bacteria to bind Gram’s iodide stain. The cell morphology and the growth pattern of the bacteria, such as cocci or rods, and distribution in pairs, chains, or clumps can also be observed.

The most widely used and currently dependable method for diagnosing bacterial infections is culture and sensitivity. Since 94% of odontogenic infections contain anaerobic bacteria, it is important for the clinician to identify both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria by using culture swabs for each type. Certain types of swab culture systems, however, are capable of preserving both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, at least for reasonably brief periods of time. The surgeon should check the expiration date of culture swabs before using them because of their short shelf life.

A major limitation of conventional culture methods is that approximately 60% of the oral flora, for example, are not yet culturable by available methods. Therefore a large proportion of the species found in a given specimen may not be identified. On the other hand, it is reassuring to note that conventional culture methods do seem to yield clinically useful information. Another limitation of conventional culture methods is the time required for identification of fastidious organisms such as the slow-growing oral pathogens. Often, species identification cannot be made until 7 days or more after sampling. By this time, the patient’s clinical course has usually either improved or deteriorated dramatically. Antibiotic sensitivity testing may require up to another 7 days in the case of slow-growing organisms. More timely availability of culture and sensitivity results would be most useful to clinicians. Practical clinical indications for culture and sensitivity testing are listed in Table 116-3 .

| INDICATION | EXAMPLE |

|---|---|

| Potentially serious or life-threatening infection | Infection in the masticator, perimandibular, or deep neck spaces |

| Need for inpatient care | Poorly controlled systemic disease, e.g. diabetes |

| Immunologic compromise | Cancer chemotherapy |

| Failed prior treatment | Therapeutic failure of prior course of antibiotic |

| Recurrent infection | Recurrent osteomyelitis |

| Hospital-acquired infection | Sinusitis after prolonged intubation |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses