Fig. 2.1

Lateral view of the maxillary bone with the external walls of the maxillary sinus: orbital floor (pink), anterior wall (yellow), posterior wall (purple)

Initially, the maxilla bone presents a medial wall with a large triangular opening with a downward tip named the hiatus (hiatus maxillaris; Fig. 2.2). Progressively, the lateral wall of the nasal cavity is covered by adjacent bony structures: the lacrimal bone (unguis) anteriorly, the inferior turbinate (concha nasalis inferior) inferiorly, the uncinate process of the ethmoid superiorly, and the vertical part (lamina perpendicularis) of the palatine posteriorly. By connective tissue and mucosa the hiatus was progressively reduced at only one or two small openings named ostia located under the space of a shelf-like structure of the middle turbinate. Frontal sinus and anterosuperior cells of the ethmoid opening are also in the middle meatus (Fig. 2.3).

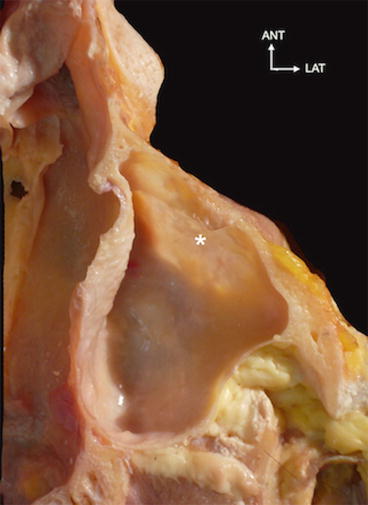

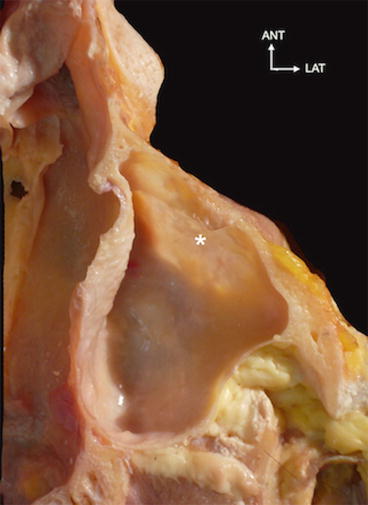

Fig. 2.2

Medial view of the isolated maxillary bone with the large triangular opening of sinus (asterisk): the hiatus of the maxillary bone

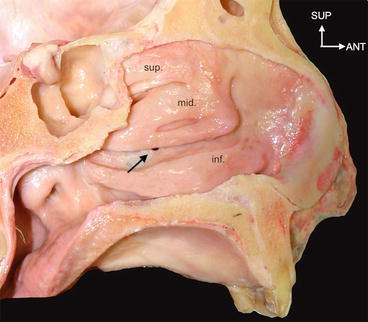

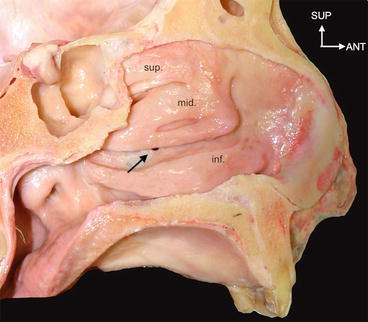

Fig. 2.3

Lateral wall of the nasal fossa with three turbinates (superior, middle, and inferior) and under the middle turbinate the ostium of the maxillary sinus (arrow)

The posterior wall of the maxillary sinus (tuberosity) is bound by the pterygoid space (fossa) form the first method of vascular and nervous supply.

The anterolateral wall separates the soft tissues of the cheek from the sinus and was the principal method of sinus floor elevation by canine fossa (related to the ancient name of the levator labii anguli muscle, the canine muscle, in reference to the canine appearance when contracted; Fig. 2.4).

Fig. 2.4

Horizontal section of the maxillary sinus. See the thinness of the anterior wall of the sinus (asterisk indicates the canine fossa)

The superior wall of the sinus forms the most important part of orbital floor. In the case of traumatic injury to the eyeball, this floor can be broken or disrupted and the pressure evacuates downward to protect the ocular globe (Fig. 2.5).

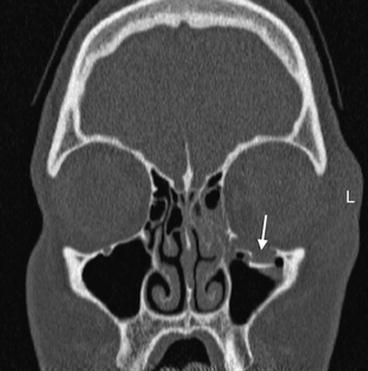

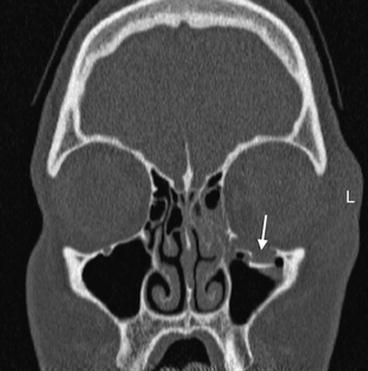

Fig. 2.5

Eye-ball traumatism with fracture (arrow) of the orbital floor in the direction of the maxillary sinus

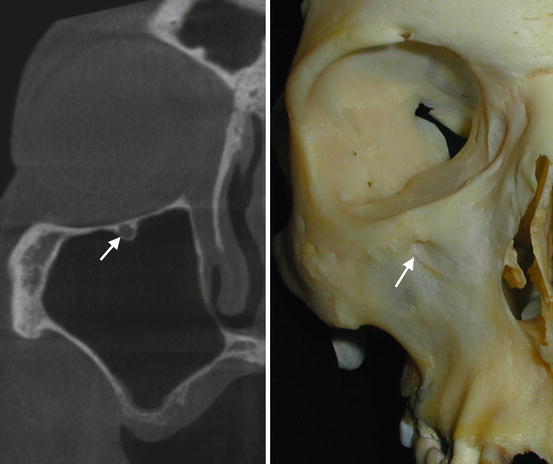

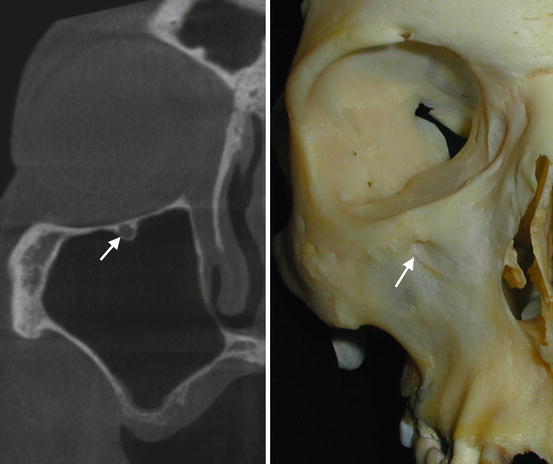

In the superior wall of the maxillary sinus we found the infraorbitalis canal for nervous fibers of the anterosuperior teeth descending into the anterolateral wall. Finally, the infraorbitaris foramen permits the passing of sensitive nervous fibers and vascular bundles to the cheek tissues (Fig. 2.6).

Fig. 2.6

Infraorbital canal on a coronal CT and its endpoint in the infraorbital foramen in the skull (white arrows)

The last wall of the maxillary sinus forms the alveolar process of the maxillary bone with great variations in relation to the teeth roots and apices, sometimes between the teeth and between the roots such as a procident sinus.

The space under the middle turbinate is an anatomical complex with from anterior to posterior the uncinate process, the infundibulum, and the ethmoid bulla. At the inferior extremity of the infundibulum we found the oval-shaped maxillary sinus ostium. One or more accessory ostia can exist in 10 % of cases (Jog and McGarry 2003).

The middle meatus extends between the middle and the inferior conchae. The upper and anterior part of the middle meatus leads into a funnel-shaped passage that runs upward into the corresponding frontal sinus. This passage, the infundibulum, constitutes the channel of communication between the frontal sinus and the nasal cavity.

On the lateral wall of the middle meatus a deep curved groove or gutter that commences at the infundibulum and runs from above downward and posteriorly is seen. The groove is termed the hiatus semilunaris and it is the opening of the anterior ethmoid cells and the maxillary sinus. The slit-like opening of the maxillary sinus lies in the posterior part of the hiatus semilunaris (Figs. 2.7 and 2.8).

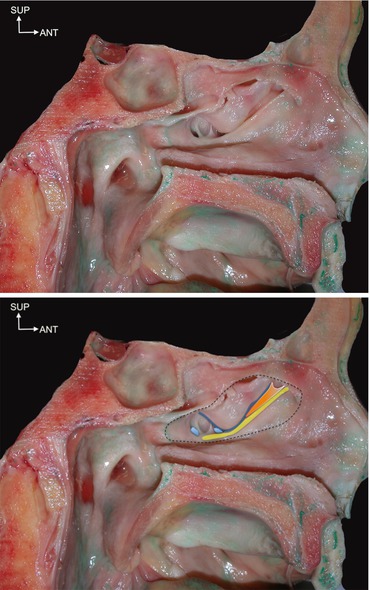

Figs. 2.7 and 2.8

Lateral view of the ostiomeatal complex under the middle concha (sectioned along the dotted line). Uncinate process (yellow line), infundibula (orange zone), ethmoid bulla (blue line), and two ostia of the maxillary sinus (light blue)

The upper boundary of the hiatus semilunaris is prominent and bulging. It is called the bulla ethmoidalis. Above the bulla is the aperture of the middle ethmoidal cells.

The orifice by means of which the great sinus communicates with the middle meatus lies in the medial wall of the sinus much nearer the roof than the floor, a position highly unfavorable for the escape of fluids that may collect in the cavity.

Sometimes, a second orifice circular in the outline will be found, situated lower down. When it is present it opens into the middle meatus immediately above the middle point of the attached margin of the inferior concha.

2.4 Sinus Vascularization

The maxillary sinus is embedded in numerous anastomoses of various arteries receiving blood supply, in reverse order we found the superior alveolar arteries (through the tuberosity), the greater palatine artery (posterior and medial wall), the sphenopalatine artery, the pterygopalatine, the infraorbital artery in the anterior wall and posterior lateral nasal artery in the medial wall.

The anatomical course of the anterior maxillary wall and the alveolar process arteries is essential for sinus lift procedures. During these surgeries certain intraosseous vessels may be cut, causing bleeding complications in approximately 20 % of osteotomies (Elian et al. 2005).

Since the study by Solar et al. (1999) was published it has been well established that the lateral maxilla is supplied by the branches of the posterior superior alveolar artery and the infraorbital artery, which form two kinds of anastomosis in the lateral wall: intraosseous in 66 % of patients in Rodella et al. (2010) (Figs. 2.9 and 2.10) and in 100 % of cases in Traxler et al. (1999) (Fig. 2.11).

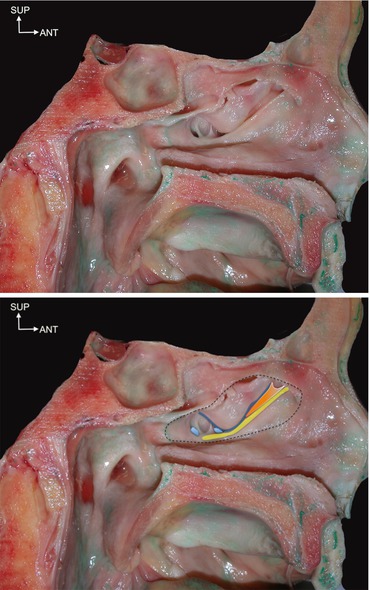

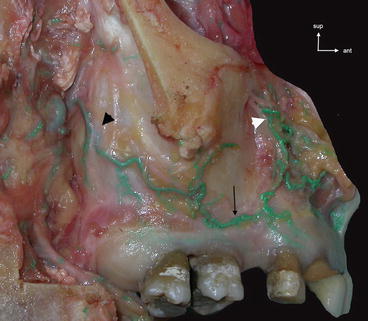

Fig. 2.9

External vascularization of the lateral walls of the maxillary sinus (arteries injected with green latex). Anastomosis (thin arrow) between the alveolar posterosuperior artery (black arrowhead) and infraorbitalis artery (white arrowhead)

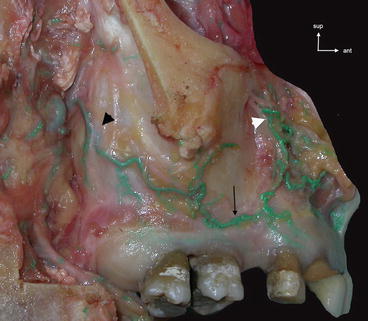

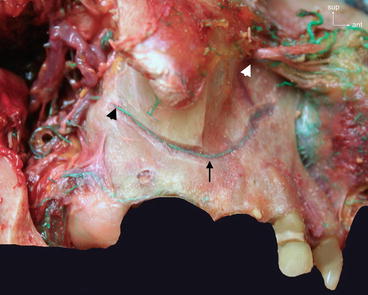

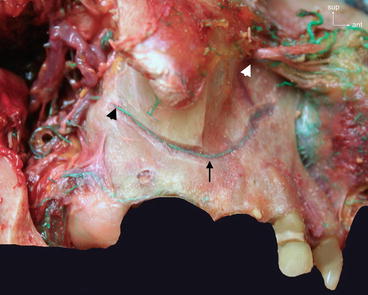

Fig. 2.10

Vascularization of the lateral walls of the maxillary sinus (arteries injected with green latex). Intraosseous anastomosis (thin arrow) between the alveolar posterosuperior artery (black arrowhead) and infraorbitalis artery (white arrowhead)

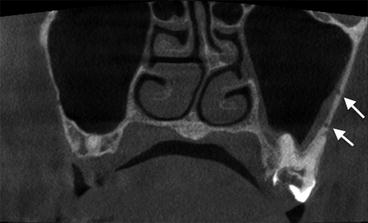

Fig. 2.11

CBCT axial section of the maxillary sinus with intraosseous artery in the canine fossa (white arrows)

Some variations such as two parallel arteries (Figs. 2.12 and 2.13) were found by Rodella et al. (2010) in 10 % of anatomical subjects in her study or an extraosseous anastomosis could be observed in 44 % of cases by. Traxler et al. (1999).

Fig. 2.12

Two intraosseous arteries in the same lateral wall of the maxillary sinus (white arrows)

Fig. 2.13

Double intraosseous artery in the lateral wall of the maxillary sinus (white arrows)

Arteries had a mean diameter of 1.6 mm and the mean distance between the intraosseous anastomosis and the alveolar ridge was 19 mm in anatomical studies versus 16 mm from the alveolar ridge in CT studies (Mardinger et al. 2007; Elian et al. 2005).

Only intraosseous arteries can be identified on CT in 53 % of cases (Elian et al. 2005) to 55 % (Mardinger et al. 2007) versus 100 % in cadaveric anatomical studies. CBCT studies give the same data with 52.8 % anastomosis observed by Jung et al. (2011) on CBCT of 250 patients.

Geha and Carpentier (2006) observed that intraosseous anastomosis sometimes occurs at the interface of the sinus membrane and the internal side of the sinus wall. In the case of osseous sclerosis induced by chronic sinusitis conditions, this type of anatomical variation could be embedded and finally became intraosseous and well-defined on CBCT or CT (Fig. 2.14).

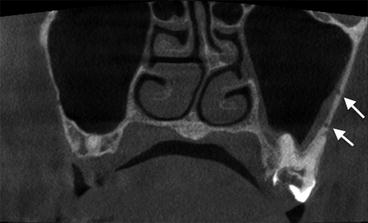

Fig. 2.14

Large intraosseous artery in the sclerotic sinus wall (white arrows)

The venous system is collected either by a single trunk, which is a continuation of the sphenopalatine vein, or by three venous plexuses: the anterior and posterior pterygoid plexuses, and the alveolar plexus. The anterior and posterior pterygoid plexuses converge through the lateral pterygoid muscle and connect with the alveolar plexus, which drains partly into the maxillary vein and partly into the facial vein (Dargaud et al. 2001).

2.5 Sinus Innervation

The posterior superior alveolar nerve, a branch of the infraorbital nerve, is divided into two branches, one for the tuberosity and sinus antrum and another one, the lowest, to reach the molar teeth apices.

In the roof of the sinus, the infraorbital canal permits the passing of infraorbital sensitive nerves (Fig. 2.15) and gives off two other nerves: the middle superior alveolar nerve, not constant, coursing along the postero- or anterolateral wall of the sinus to the premolar apices; and the anterior superior alveolar nerve, given off 15 mm before the infraorbital foramen, for the incisal and canine apices. These nerves can sometimes cross the surgical way of the sinus lift procedures in the canine fossa (Fig. 2.16). Some neuropathic pain can result from the section and aberrant healing of these nerves during this type or surgery (Hillerup 2007).

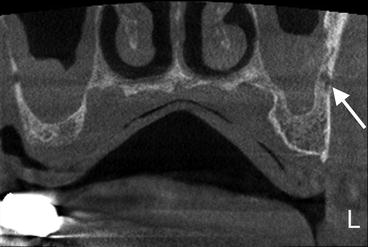

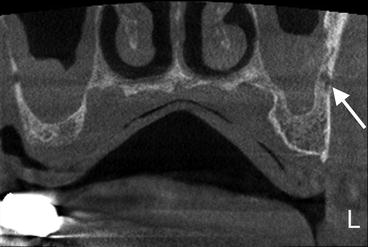

Fig. 2.15

Coronal CT view of the anatomical variation of the infraorbitalis canal (white arrow) detached from the orbital floor through the maxillary sinus

Fig. 2.16

Anatomical view of the canine fossa in the anterior lateral wall of the maxillary sinus with the passage of anterior and middle superior alveolar nerves (arrows)

2.6 Anatomical Variations

2.6.1 Maxillary Sinus Size and Volume

The maxillary sinus shows considerable variations in some cases limited to the maxillary area or it communicates with other facial bones. In humans, the volume of the maxillary sinus is close to 15 cm3. CT studies in various populations show variations within a large range. Uchida et al. (1998) on 38 sinus CTs found an average volume of 13.6 ± 6.4 cm3 within a range from 3.3 to 31.8 cm3. In other populations, Sahlstrand-Johnson et al. (2011), in her study of 110 sinus CTs, found that the maxillary sinuses are larger in males than in females (18 vs 14.1 cm3) with a mean volume of 15.7 ± 5.3 cm3 and a range 5 to 34 cm3. Thus, if the maxillary sinus varies extremely in size, the authors cannot find any statistical correlation between this volume and with age, but only sinus pneumatization increasing with tooth loss.

According to the literature, the dimensions of the sinus vary and range from 22.7 to 35 mm in mesiodistal width, 36–45 mm in vertical height, and 38–45 mm deep anteroposteriorly (van den Bergh et al. 2000; Uthman et al. 2011; Teke et al. 2007).

In some rare cases, we have found an hypoplasia of the maxillary sinus sometimes misdiagnosed as chronic sinusitis on panoramic radiographs (Figs. 2.17 and 2.18). Some authors have found a prevalence of unilateral hypoplasia of 7 % on CT (Kantarci et al. 2004) to 10.4 % (Bolger et al. 1990). This hypoplasia may be related to the aberrant anatomy of the uncinate process.

Fig. 2.17

Coronal CT view of the right microsinus

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses