Chapter 10 Analysis of NCPAP failures

1 INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) is characterized by intensive snoring and daytime sleepiness, due to repeated obstruction of the upper airway during sleep. OSAS is defined as periods of complete cessation of oronasal airflow for a minimum of 10 seconds (apnea) and periods of more than 30% reduction in oronasal airflow, accompanied by a decrease of more than 4% in ongoing paO2 (hypopnea), with an Apnea/Hypopnea Index (AHI) of more than 5, accompanied by daytime symptoms.1 The prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in the middle-aged is 2% of women and 4% of men.2 It has been estimated that at least 80% of all moderate and severe OSAS in the general population is likely being missed.3

OSAS has adverse effects on daytime quality of life such as daytime sleepiness and diminished intellectual performance. OSAS is of growing significance because of its increasingly recognized high incidence and association with neurocognitive symptoms and cardiovascular disease.4,5 In severe OSAS there is an increased risk of being involved in traffic accidents.6,7 Therefore OSAS is treated for its symptoms, in the attempt to reduce morbidity and mortality.

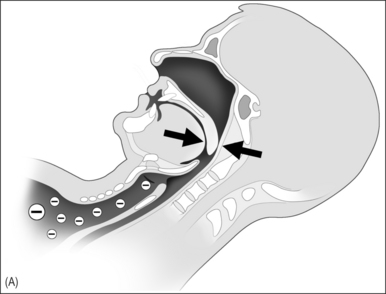

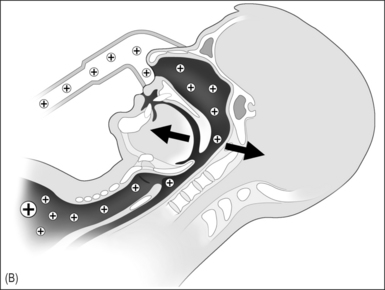

In 1981 nasal continuous positive airway pressure (NCPAP), which acts as a pneumatic splint, was introduced as treatment of OSAS and has been considered the gold standard for treatment of severe OSAS since (Fig. 10.1A & B).8 It is a safe therapeutic option with few contraindications or serious side effects.9 Unfortunately many patients experience NCPAP therapy as intrusive and the acceptance and (long-term) compliance of NCPAP are at best moderate. A vast body of literature was published in the last decade on the subject of (long-term) compliance of NCPAP, with rates ranging from 46% to 89%.10–23 Improvements in NCPAP technology, in particular the introduction of automatic adjustments of the NCPAP pressure throughout the night (auto-CPAP), and attempts to enhance acceptance and compliance have been introduced.24–32 We were interested to see if these actions have led to better acceptance and compliance as compared to earlier reported data.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

NCPAP has come to be regarded as the gold standard treatment for OSAS in the last decade.33 In the pioneering phase of management of OSAS this view was understandable as uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) was the almost exclusively surgical alternative for OSAS treatment. Metaanalysis by Sher et al. in 1996 showed a success rate of UPPP (in unselected patients) of only 40%.34

Various studies have attempted to analyze compliance. The results vary and do not all apply the same criteria, especially regarding compliance and therapy failure. Furthermore there are no precise recommendations available concerning the necessary duration of daily and weekly use. Twenty-four patients were unavailable for follow-up. Of the remaining 232 patients, 58 (25%) were failures, while 75% were still using NCPAP after 2 months to 8 years of follow-up; 138 (79%) of these 174 patients were considered compliant, as defined above, as compared to 46–89% as reported in earlier series.10–23 Including the 58 failures, only 59.5% of patients can be seen as compliant. There were no statistical differences in compliance between the fixed pressure CPAP and auto-CPAP. Although it was to be expected that patients with a higher AHI and higher Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) would be more compliant, we found no difference for AHI and ESS.

Actual use of NCPAP, as reported in the literature, ranged from 3.7 to 7.2 h in the years 1992 to 2002.11,13,14,16–18,20,22,25,26,33,35–41 These data were usually obtained from fixed NCPAP by time counter registration. The average of NCPAP, both fixed and auto-CPAP, in our series is slightly longer (6.4 h) as compared to the mean of earlier studies (5.4h) on this subject. The number of hours per night of use in our series was, however, estimated by the patient, and therefore it may be that the actual use is lower.

Surgery will not become the first treatment of choice in all patients. However, success rates of UPPP in well-selected patients (obstruction at the retropalatal level only) reach 70–80%.35,36 In patients with obstruction at the retrolingual level comparable success rates have been reported.37 In the light of failure rates for NCPAP therapy it is hard to maintain that NCPAP should always be the treatment of first choice. Therefore, a gradual shift can be expected to take place to alternatives to NCPAP, being a combination of surgery,38,39 and possible positional conditioning,40,41 in well-selected, well-informed patients, while NCPAP therapy in those patients will still be in reserve in case of surgical failure.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses