Fig. 8.1 Injection sites for glabellar lines.

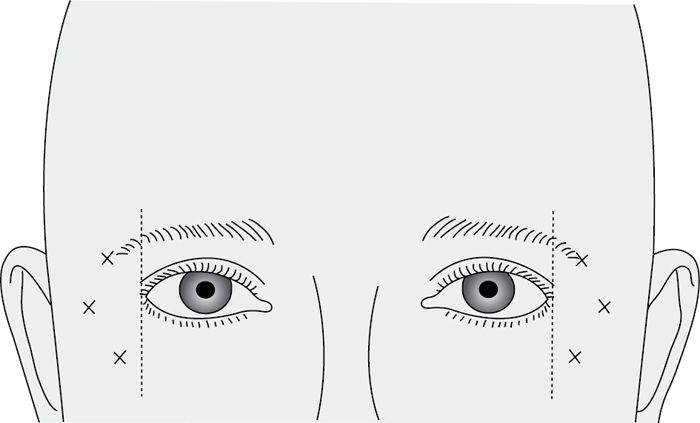

Fig. 8.2 Injection sites for crow’s feet.

Practical considerations

• Use of topical anaesthesia and a fine gauge needle (30G, yellow) decreases patient discomfort. Use a 1mL syringe.

• 3 units of Dysport® are equivalent to 1 unit of Botox® or Vistabel®. Dysport® has a quicker onset and diffuses more than Botox®—efficacy is equivalent. Each injection can diffuse 2–3cm radially.

• May take up to 7–14 days to have its effect.

• Length of action is between 4 and 6 months.

• Dilute 100 or 50 units Botox® into saline for injection.

• 100 units in 5mL gives 2 units in 0.1mL; 100 units in 2mL gives 5 units in 0.1mL. Use small volumes and doses at each site—the greater the dilution the greater the diffusion.

• Common doses are:

• glabella 5–8 units in 5 sites;

• forehead 3–6 units in 6–10 sites (stay medially to preserve eyebrow arching—2 rows may be needed in a high forehead).

• To avoid extra-ocular muscle compromise—inject well away from orbital rim.

• Avoid total paralysis of the forehead which produces an unnatural appearance. It is better to top it up later than overdo it initially.

• The lateral eyebrow can be arched to produce an aesthetically pleasing result by preserving function in the lateral frontalis and treating orbicularis oculi lateral to the orbit. Paralysis of the lateral part of frontalis causes loss of arching and resulting ‘angry appearance’.

• Use of Botox® in the treatment of naso-labial grooves is best combined with a filler. Injection of the levator labii alaeque nasi causes depressed upper lip elevation and can therefore be utilized in the treatment of the gummy smile.

• Neck bands can be treated effectively by injecting 3–5 units at 1–1.5cm intervals.

Complications

In the hands of experienced clinicians complications following Botox® for cosmetic reasons should be rare. Reported complications include:

• Extra-ocular muscle paralysis resulting in strabismus and diplopia. This normally corrects after ~6 weeks.

• Ptosis of the upper eyelid and brow.

• Asymmetrical muscle paralysis.

• Bruising.

• Haematoma.

Contraindications

Botulinum toxin should be avoided in patients suffering from neuropathic/neurological disorders. Injection into an infected site should be avoided.

Fillers

Dermal fillers are injectable substances used to augment the skin. They are used in the cosmetic treatment of static and dynamic wrinkles, as well as deep grooves such as naso-labial folds and marionette lines. They are also used in the treatment of depressed scars. Lips can be augmented with certain fillers.

For many years, the most commonly used agent was collagen. The major drawback with collagen is the possibility of allergy. Skin testing is therefore required prior to treatment. The most commonly used fillers in use at the present include the following:

• Restylane® and Perlane® are both made from hyaluronic acid, a natural carbohydrate polymer found in the ground substance of connective tissue. They last up to 6 months.

• Hylaform® is also a hyaluronate-based filler.

• Sculptra® is polylactic acid which stimulates production of autogenous collagen. The effect is therefore delayed and several treatments are often required to achieve the desired result. It lasts 18–24 months and is used extensively to treat facial lipoatrophy in AIDS patients. It is described as a volumizer rather than a filler.

• Radiesse® is a combination of calcium hydroxyapatite microspheres in a polysaccharide gel. It lasts about 2 years and stimulates collagen formation.

• Evolence® is a porcine collagen derivative with good handling properties and effects that can last more than a year.

• Artifill® is made of synthetic microspheres suspended in a bovine collagen gel. Its effects are claimed to be permanent.

Fillers are injected intradermally or subcutaneously in order to plump out the overlying soft tissues and smooth out wrinkles. Injection technique is key to achieving good results—along the length of fine lines (linear threading technique) or injected in a fan-shaped manner from several directions to fill deeper grooves. Even injection is required to avoid subcutaneous lumps. Injection sites should be massaged to encourage even distribution.

Complications

Include haematoma formation and infection. Uneven injection can lead to subcutaneous lumps, which may be visible as well as palpable.

Resurfacing techniques

• Dermabrasion.

• Microdermabrasion.

• Laser resurfacing.

• Chemical peels.

Dermabrasion

• Involves the use of a rotary hand engine with a diamond wheel or wire brush to abrade the skin.

• Is usually carried out under local or topical anaesthesia and is used for the treatment of age changes, scarring, or photodamage.

• Is commonly used to treat acne scarring, naevi, cloasma, and facial wrinkles.

• In skilled hands it is an extremely effective technique.

• Its main advantage is that the depth of injury can be directly controlled:

• superficial dermabrasion is sufficient to treat fine wrinkles;

• deeper treatment into the papillary or reticular dermis may be necessary in the treatment of deep scarring.

• Contraindications include keloid or hypertrophic scar formation, and a history of herpes simplex infections.

• Complications include keloid or hypertrophic scarring, hyper- or hypo-pigmentation, infections, persistent erythema, and oedema. Full-thickness injury to the skin results in healing by secondary intention and consequent scarring.

Microdermabrasion

This non-invasive technique involves the use of aluminium oxide particles to ‘sandblast’ the skin. This removes the superficial skin layer and produces mild oedema resulting in temporary reduction in fine wrinkles. It may have a rejuvenating effect by stimulating new collagen formation.

Laser resurfacing

Laser resurfacing using a CO2 or erbium laser is used for similar indications to chemical peels and dermabrasion. Thermal injury to the skin results in removal of surface layers, contraction of collagen, and new rejuvenated collagen formation. The depth of injury produced is controllable with less risk of inadvertent over-treatment than with a chemical peel. It is particularly effective in the treatment of fine, non-dynamic lines and changes produced by photo-ageing. Erythematous scars can be improved and stepped scars may be treated by ‘shoulder resurfacing’.

CO2 treatment to the eyelids to produce skin contraction can be combined with transconjunctival orbital fat removal in cosmetic blepharoplasty.

Other lasers producing light of different wavelengths target various chromopores within the skin and are therefore used to treat varying conditions (Table 8.1).

Table 8.1 Lasers producing light of different wavelengths and their targets

| Laser | Wave length (nm) | Skin chromophore |

| Argon | 193 | Melanin, blood |

| KTP | 532 | Melanin, blood |

| Krypton | 531.7–647 | Melanin, blood |

| Copper vapour | 511 | Melanin, blood |

| Dye laser | 585 | Melanin, blood |

| Ruby | 694.7 | Melanin |

| Alexandrite | 755 | Melanin |

| Nd:Yag | 1064 | Melanin, blood |

| Holmium:Yag | 2100 | Water |

| Erbium:Yag | 2940 | Water |

| Carbon dioxide | 10,600 | Water |

Depending on the characteristics of the laser used, pigmented lesions including tattoos and vascular lesions may be treated.

• Laser safety: operating room personnel and patients should be protected from inadvertent ocular injury and the ETT from damage. The presence of bacterial and viral DNA has been demonstrated in the CO2 laser plume. Special masks that filter such partials have been developed and should be worn.

• Complications include:

• ocular damage;

• full-thickness burn;

• ectropion following laser blepharoplasty;

• prolonged erythema;

• milia;

• skin irritation;

• herpes simplex reactivation;

• bacterial and fungal infections;

• hyperpigmentation;

• hypopigmentation;

• hypertrophic scarring.

Chemical peels

A chemical peel is the application of a chemical agent that causes controlled destruction of the superficial layers of the skin. The superficial damage to the skin causes exfoliation and wound healing.

• Peels reduce:

• fine wrinkles;

• acne and other scars;

• pigmentation abnormalities;

• actinic keratoses;

• lentigines (solar-induced freckles).

• Common agents:

• glycolic acid;

• trichloroacetic acid (TCA);

• TCA with blue glycerine (a blue peel);

• phenol (carbolic acid).

The effect is modulated by the strength of the solution used and the number of applications, which are determined by the lesion being treated and the skin type of the patient. Care must be taken when treating the eyelids where the skin is thinnest.

• Complications:

• more likely with deeper peels and when using phenol;

• hyperpigmentation;

• persistent erythema;

• reactivation of herpes simplex infection;

• hypertrophic scarring.

Surgical techniques

Blepharoplasty

This is a procedure used to shape or modify the appearance of the eyelids. The word was first used by Von Graefe in 1818 to describe a procedure for repairing defects in the eyelids secondary to tumour excision.

The eyelids are one of the first structures of the face to develop permanent structural changes due to ageing.

• Changes in elasticity of:

• orbital septum;

• tarsus;

• orbicularis muscle;

• orbital septum.

• Result in:

• excess skin;

• wrinkles;

• pseudoherniation of orbital fat;

• baggy, tired looking eyes.

Blepharoplasty will not on its own treat malar bags or the tear-trough deformity.

Aesthetic goals

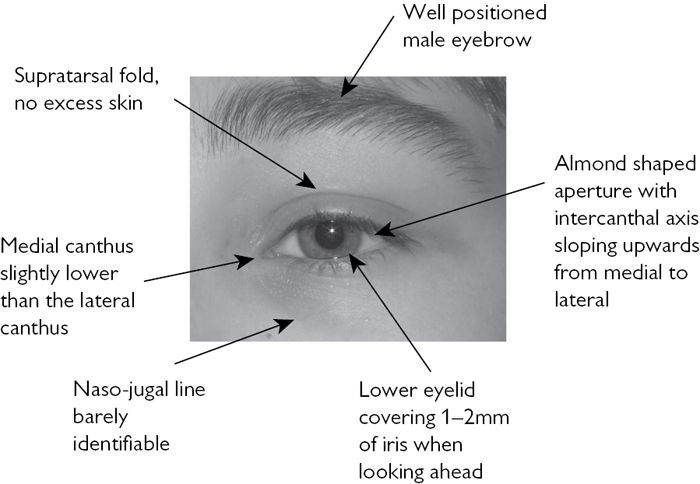

The perceived aesthetic ideals of the Caucasian eye are shown in Fig. 8.3. It is important to recognize the racial variations.

Fig. 8.3 Perceived aesthetic ideals of the Caucasian eye.

Assessment/history

As with all aesthetic patients:

• What patient perceives to be the problem.

• What are their expectations?

• Why do they want the surgery?

• Previous surgery.

• Dry eyes.

• Contact lenses.

• Diplopia.

The following areas should be assessed:

• Position of the eyebrow (sometimes a brow-lift is required).

• Amount of redundant skin.

• Symmetry, position, and relative excess of the fat pads.

• Ability to close the eyes easily.

• Position of the eyelids relative to the eyes.

Specific tests

• Snap test: examination for lower eyelid laxity. The lower eyelid is pulled down gently—it should snap back within 1s. With low elasticity this may only happen on blinking.

• Distraction test: is positive if the lower lid can be pulled down >7mm from the globe (indicates laxity of the lower lid). In these patients blepharoplasty without a lower lid tightening procedure may lead to ectropion and scleral show (the appearance of sclera below the iris when the patient looks ahead).

• Examine for compensated brow ptosis: look for descent of the eyebrows when the eye closes. This demonstrates that the brow is ptotic. In these patients frontalis activity keeps the eyebrows elevated when the eyes are open. This indicates that a brow lift may be required. Blepharoplasty in such patients may result in a worsening of their appearance.

• Location of site of herniation of fat pads: gently press on the globes and observe the areas of fat prolapse.

• Presence of Bell’s phenomenon: usually on eyelid closure the globes rotate upwards and the cornea is protected. If absent there is risk of damage to corneas after blepharoplasty.

• Ophthalmology assessment:

• should include visual fields and acuity;

• if the patient has symptoms or signs of dry eyes then a Schirmer test is indicated;

• take good standardized photographs.

Techniques of blepharoplasty

Upper

The eyelids are marked with the patient sitting up. The lower incision is marked so as to place the surgical scar within the supratarsal fold. The surgeon then pinches the excess tissue with blunt forceps until the lids separate slightly. This continues across the eyelid. Care is taken not to extend too far medially or laterally, as these areas produce visible scars. A strip of tissue including skin and orbicularis muscle is excised. If protruding fat needs to be excised from the medial and lateral upper fat pads this is achieved through small stab incision in the orbital septum. Beware a herniating lacrimal gland and the levator aponeurosis. Meticulous haemostasis is essential.

Lower

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses