12 Adult orthodontics

Why do adults undertake orthodontic treatment?

An adult may be motivated primarily by a desire to improve their dental appearance and may request orthodontic treatment. Amongst this group will be those who either refused or were not given the opportunity of treatment during their childhood, and those who may have received treatment but have been left dissatisfied with the result, often because of subsequent relapse or an inappropriate original treatment plan (Fig. 12.1). Routine orthodontics can be readily carried out in these patients, but the scope of increasingly complex treatment can be more limited in comparison to that which might be achieved in a growing child or adolescent. Moreover, adults can also present with other age-related problems that must be considered when providing orthodontic treatment (Box 12.1).

Box 12.1 Special problems associated with orthodontic treatment in adults

A number of features associated with adult patients can make orthodontic treatment more challenging and these all need to be taken into consideration when planning and embarking upon treatment (Nattrass & Sandy, 1995).

Growth

Periodontal Tissues

The prevalence of periodontal disease and loss of attachment increases with age, becoming more common in adults. An adult patient should undergo a complete clinical and radiographic assessment of their periodontal status before embarking on orthodontic treatment (Johal & Ide, 1999). Previous attachment loss does not preclude orthodontics, but active periodontal disease will require treatment and evidence of stabilization before any appliances are placed (Table 12.1). An excellent standard of plaque control should be attained and then maintained throughout treatment, if necessary with professional supra- and subgingival scaling. Teeth with previous attachment loss and reduced bony support will also respond differently to orthodontic force:

Restorations

Adult patients often have a heavily restored dentition, which can complicate the choice of orthodontic extractions and necessitate the bonding of appliances to ceramics or alloys. Root canal-treated teeth are amenable to orthodontic tooth movement as long as they are symptomless and correctly obturated (Drysdale et al, 1996).

Orthodontics as an adjunct to restorative treatment

Adults can often present with an incomplete dentition, permanent teeth having been lost prematurely as a result of caries, periodontal disease or trauma. This can lead to alterations in position of the remaining teeth due to drifting, tipping, rotation or overeruption (Fig. 12.2). Whilst there are obvious negative aesthetic consequences associated with tooth loss and alterations in the position of adjacent teeth, occlusal instability and functional problems can also occur and contribute to:

Orthodontics as an adjunct to periodontal treatment

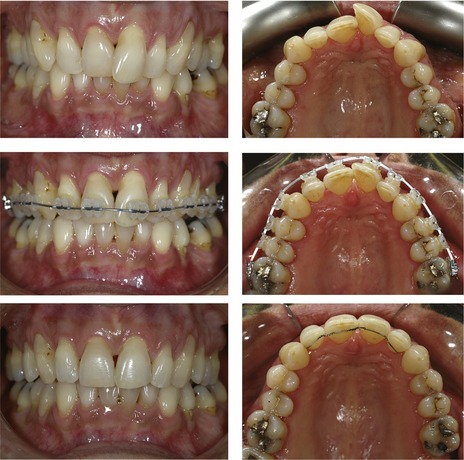

Tooth migration can also occur as a consequence of attachment loss secondary to periodontal disease. In particular, the labial segments can procline significantly, resulting in an increased overjet, generalized spacing and extrusion with lengthening of the clinical crowns (Fig. 12.4). Orthodontic treatment can be carried out to retract or intrude these teeth and close spaces, but permanent retention is usually required to maintain the new position. Orthodontic intrusion can also reduce the clinical crown height and improve attachment levels if light forces are employed and associated with minimal tipping (Melsen, 2001). A prerequisite before embarking upon any orthodontic treatment in the periodontally compromised patient is stabilization of the disease process itself (Table 12.1).

Figure 12.4 Rotation and extrusion of the UL1 as a result of periodontal disease.

The position of the UL1 was corrected with fixed appliances and permanent retention.

Table 12.1 Treatment targets in patients with active periodontal disease prior to embarking on orthodontic treatmenta

Orthodontics and orthognathic surgery

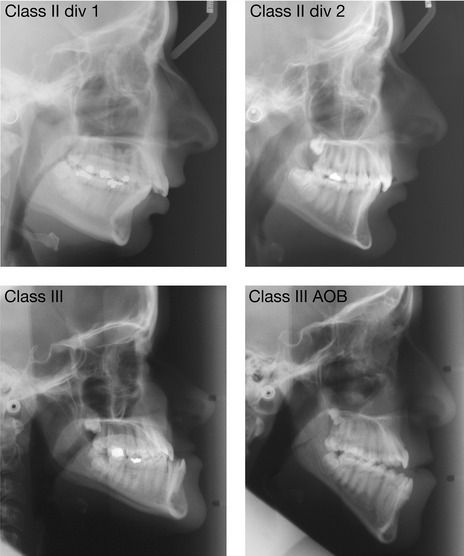

A malocclusion associated with any significant discrepancy in the dentofacial skeleton of an adult requires a combination of orthodontics and surgical repositioning of the jaws for definitive correction (Fig. 12.5). These skeletal problems can include:

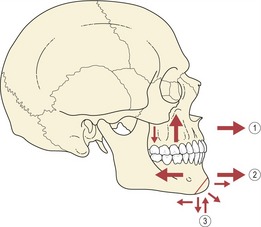

Orthognathic surgery can involve a range of surgical movements, which achieve repositioning of the maxilla or mandible within the facial skeleton (Fig. 12.6). Surgery of this kind does not affect any inherent growth capacity that may reside in the jaws and for this reason it is only carried out once skeletal growth has ceased, in the adult. This is particularly important for class III cases with mandibular excess, where continued forward growth of the mandible after backward surgical repositioning can lead to the reappearance of a reverse overjet if the surgery is carried out before growth has ceased.

Why do adults present for orthognathic surgery?

A minority of patients may exhibit a significant preoccupation with an imagined, relatively minor or non-existent defect in their facial appearance: a condition known as body dysmorphic disorder (Cunningham & Feinmann, 1998). Any suspicion of this should elicit referral for a more formal psychiatric assessment prior to embarking on any combined treatment.

Presurgical orthodontic treatment

There are two principle aims of presurgical orthodontic treatment:

These aims are achieved within a number of overlapping phases, primarily during presurgical treatment through orthodontic tooth movement, although occasionally some surgical intervention may also be required, particularly for expansion (Box 12.2) or levelling of the maxillary arch. Surgically-assisted expansion is carried out before the definitive osteotomy, whilst surgically-assisted levelling usually takes place with it (Table 12.2). Some controversy exists regarding the amount of orthodontic treatment that should be completed prior to surgery (Box. 12.3), but conventional planning requires full decompensation.

Table 12.2 Phases of orthodontic treatment for orthognathic patients

Box 12.3 How much orthodontic treatment is required prior to surgery?

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses