Chapter 9

Radiographic Examination and Special Tests

Aim

This chapter aims to outline the indications and contraindications for using special tests during a detailed periodontal assessment. Advantages and disadvantages of different types of radiographic examinations are discussed alongside other special tests.

Outcome

The outcome of reading this chapter will be that the practitioner should be clear about which radiographs to take in which situations, and how to interpret results in terms of a periodontal assessment and document radio-graphic reports.

The clinical examination precedes any other “hands-on” investigation and determines whether, and if so which, special tests need to be performed. They are not always required.

The Radiographic Examination

Radiographs are used to provide information largely about hard tissues and are recommended only when such data provides positive added value to that already held. There are a number of points to consider:

-

A balance needs to be struck for individual patients in individual circumstances between the advantages of the additional diagnostic yield gained from taking radiographs and the potential disadvantages of exposure to radiation.

-

If radiographs are to be taken, the clinician must choose films that will provide the highest diagnostic yield for the least possible radiation.

-

There should be a signed and dated radiographic report in the notes pertaining to all radiographs taken.

-

Should there be difficulty in interpretation of radiographs an opinion should be sought from a radiologist and a written report requested.

Choice of Techniques

Fast (E- or F-speed) films and narrowly collimated X-ray beams should be used to decrease radiation doses as much as possible. Three types of film are routinely used in conventional dental radiography: dental panoramic tomograms, bitewings and periapicals.

Dental panoramic tomograms (DPT)

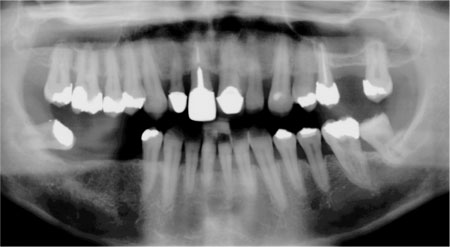

Dental panoramic tomograms give a general overall view of the mouth, permitting a general examination of the teeth and jaws. An example is shown in Fig 9-1. Unfortunately, distortions in the horizontal plane are frequently found. In particular, DPTs are less clear around the lower anterior region owing to both superimposition of the cervical spine and distortion in this area. The quality of DPTs has improved greatly in recent years, though most clinicians would accept that the image quality is not yet as good as that from intra-oral films. The radiation dose from a DPT is, however, significantly less than that from full-mouth intra-oral radiographs.

Fig 9-1 DPT radiograph.

Bitewings

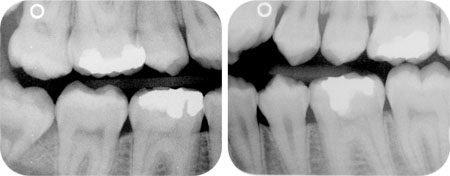

Bitewings can be used in two planes – vertical or horizontal. Horizontal bitewings (Fig 9-2) are often taken in general practice to look for inter-proximal caries and can also be used to look for marginal bone loss in mild to moderate periodontal disease. In such circumstances, a single film will show the bone crest in both arches and the radiation dose is relatively small. This type of film does not, however, show the periapical tissues and sometimes the furcation areas are also not visible. Compared to horizontal bitewings, vertical bitewings show a greater percentage of the teeth being filmed though fewer teeth are displayed on each one. Vertical bitewings may be used to display the marginal bone crest and the furcation areas of the filmed teeth though often the periapical areas are not visible.

Fig 9-2 Horizontal bitewing radiographs.

Periapicals

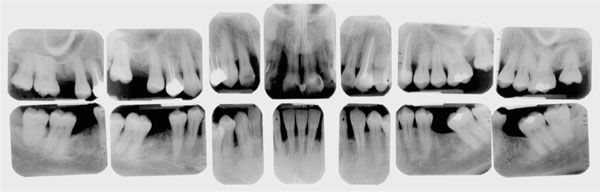

Periapicals are the films of choice when the finest detail is required and imaging of the apical and periapical tissues is necessary. Periapical views (PAs) will give the most information possible about individual teeth and their support – including the furcation and periapical areas – though if full mouth films are taken there is an increased radiation dose for the patient compared to taking a single DPT. The best results are obtained using a long cone paralleling technique with the use of film holders, as this produces the least distortion. The bisecting-angle technique should be avoided because it results in underestimation of bone loss. If the clinician wishes to assess the root length and shape then the PA is the film of choice. A set of full-mouth peri-apical films is shown in Fig 9-3. In order to minimise radiation dosage it would be unusual to repeat full-mouth periapicals within two years. It may, however, prove necessary to repeat individual periapical films within this time if particular problems arise, though there must be a compelling clinical reason to do so.

Fig 9-3 Full-mouth periapical radiographs.

The newer technique of digital radiography is becoming more widely available and presents a number of advantages, not least because it reduces the radiation exposure for the patient. In addition, it permits varied manipulation of the images produced and facilitates the assessment of specific measurements. Digital subtraction radiography (DSR), in particular, is useful for highlighting small changes in bone loss over time. For accurate comparisons using this technique, it is essential that the films being examined have been taken in precisely the same way. The use of film holders and stents, etc. is required to achieve this, which inherently makes the physical process rather more complicated and time-consuming. Switching to this technology involves considerable capital outlay but it seems to be where the future lies.

Which Films to Take

There are no fixed rules for this but Table 9-1 is a guide.

| Disease | Distribution | Severity | Radiograph |

| Gingivitis | None | ||

| Periodontitis | generalised | mild (LOA ≤ 3mm) | DPT |

| moderate (LOA >3mm but <5mm) | DPT and supplemental films of localised areas (e.g. furcation involvements) using PAs or vertical bitewings | ||

| severe (LOA >5mm) | periapicals of standing teeth or DPT if considering clearance | ||

| Periodontitis | localised – posterior teeth only affected | mild | horizontal bite-wings |

| moderate | vertical bite-wings | ||

| severe | periapicals of affected teeth or DPT initially ± supplemental PAs | ||

| Periodontitis | localised – anterior teeth only affected | mild | periapicals of affected teeth or DPT initially ± supplemental PAs |

| moderate | as above | ||

| severe | as above | ||

| Periodontitis | localised involving anterior and posterior teeth | mild | DPT |

| moderate | DPT initially ± vertical bitewings for posteriors ± PAs for anterior teeth | ||

| severe | periapicals of standing teeth or DPT initially ± supplemental PAs |

Advantages of Radiographs

Radiographs clearly facilitate visualisation of hard tissues, thereby enabling examination of root and bone anatomy and pathology, prior to preparation of the radiological report.

The Radiological Report

The rate of change is often significant so documentation of radiological findings is important as it permits longitudinal examination of features over time. When preparing the report there should be consideration of the following points. Negative findings should also be included.

-

Charting of the teeth present.

-

Bone loss. Consideration of this is important in periodontal diagnosis. It should be remembered, however, that only interproximal bone can be examined with any clarity from radiographs, as the high radio-density of the teeth themselves prevents visualisation of bone overlying them. Three aspects of bone loss should be considered: severity, pattern and distribution.

The severity

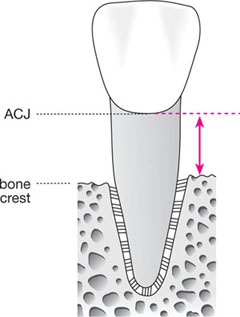

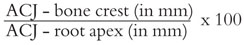

In the past this used to be calculated as a simple linear measurement in millimetres (mm) from the ACJ to the bone crest (Fig 9-4). This was subsequently judged to be an inadequate method, for a number of reasons. First, it took no cognisance of the original root length. This is significant as a 5mm linear loss of bone in someone with short roots is much more serious than the same loss occurring in someone with much longer roots. Secondly, it was recognised that a radiograph presents only an image of a tooth or teeth and that this image may be foreshortened or lengthened. Direct measurements taken from a radiograph may thus be similarly distorted, making any results gained questionable at best. The solution is to look at the percentage of the root no longer covered by bone, as this proportion will not change irrespective of foreshortening or lengthening. The measurement of bone loss is thus represented by the formula:

Fig 9-4 Diagram to illustrate old-style linear measurement of bone loss from ACJ to bone crest.

Thus, for example, a surface may show 50% bone loss.

The pattern

/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses