Prosthetic Options in Implant Dentistry

Carl E. Misch

Implant dentistry is similar to most aspects of medicine in that treatment begins with a diagnosis of the patient’s condition. Many treatment options stem from the diagnostic information. Traditional dentistry provides limited treatment options for completely edentulous patients because a complete denture is the only option. In partial edentulism, more options exist, but there are also limitations because the dentist cannot add abutments, so the restoration design is directly related to the existing oral condition. On the other hand, implant dentistry can provide a range of abutment locations in either completely or partially edentulous patients. Bone augmentation may further modify the existing edentulous condition in both the partial and total edentulous arch and therefore also affects the final prosthetic design. As a result, in implant dentistry, a number of treatment options are available for most partially and completely edentulous patients. Therefore, after the dental diagnosis of the current stomatognathic system is complete, the implant treatment plan of choice is patient and problem based. Not all patients should be treated with the same restoration type or design even when their oral conditions are similar.

Almost all human-made creations, whether art, buildings, or prostheses, require the end result to be visualized and precisely planned for optimal results. Blueprints indicate the finest details for buildings and are fabricated before the actual construction begins. The end result should be clearly identified before the project begins and even before foundation requirements are established. Yet implant dentists often forget this simple but fundamental axiom.

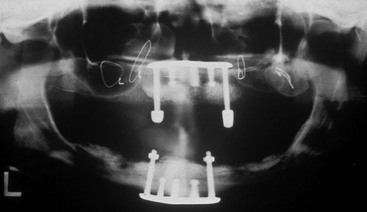

Historically in implant dentistry, a predetermined implant and the bone available for implant insertion dictated the number and locations of dental implants. The prosthesis then was often determined after the position and number of implants were selected (Figure 9-1). This concept is now being reintroduced with computed tomography technology directed toward finding existing bone locations for implant insertion. However, the ideal goal of implant dentistry is not to place implants. Rather, the ideal goals of implant dentistry are to replace a patient’s missing teeth to normal contour, comfort, function, esthetics, speech, and health regardless of the previous atrophy, disease, or injury of the stomatognathic system. It is the final restoration, not the implants, that accomplishes these goals. In other words, patients are missing teeth, not implants.

To satisfy predictably a patient’s needs and desires, the prosthesis should first be designed. In the stress treatment theorem, the final restoration is first planned, similar to the architect designing a building before making the foundation.1 Every building construction is designed with detailed blueprints prior to the foundation determinants. Similar guidelines should be used in implant dentistry. Only after the prosthesis is envisioned can the abutments, implant bodies and available bone requirements be determined to support the specific predetermined restoration.2

Completely Edentulous Prosthesis Design

Completely edentulous patients are too often treated as though cost were the primary factor in establishing a treatment plan. However, the doctor and staff should specifically evaluate and ask patients about both their needs and desires.3 Some patients have a strong psychological need to have a fixed prosthesis (FP) as similar to natural teeth as possible. On the other hand, some patients do not express serious concerns whether the restoration is fixed or removable as long as specific problems are addressed. To assess the ideal final prosthetic design, the existing anatomy is evaluated after it has been determined whether a fixed or removable restoration is required to address patient desires. An axiom of implant treatment is to provide the most predictable, most cost-effective treatment that will satisfy the patient’s anatomical needs and personal desires.

In a completely edentulous patient, a removable implant-supported prosthesis is often the treatment planned because of reduced cost, and it may offer several advantages over a fixed implant restoration. The reduced cost is related to fewer implants required when the soft tissues are also used to support the prosthesis. In these cases, the implants are placed in the anterior regions, and the implants are primarily used for improved retention and to add some stability to the restoration. Because the implants are inserted into the anterior regions of the jaws for this treatment option, less bone augmentation is required. The anterior regions of the jaws have more available bone in height than the posterior regions. Posterior regions of the jaws also resorb four times or faster than anterior regions. Because bone augmentation is usually not required, the overall treatment time is reduced because the bone graft does not require maturation for 4 or more months. Facial esthetics of a completely edentulous patient may be enhanced by a removable prosthesis (RP), especially in the maxilla. The facial flanges of the overdenture may support the lips and face when bone width and height is lost. These contours do not affect oral hygiene procedures because the prosthesis may be removed. The prosthesis may also be removed at night to reduce the risk of nocturnal parafunction. In addition, long-term complications may be easier to treat because the prosthesis may be removed and corrected in the dental laboratory (Box 9-1).

There are also many benefits of a fixed implant restoration compared with an RP. A fixed implant restoration may be indicated for either partially or completely edentulous patients. The psychological advantage of fixed teeth is a major benefit, and edentulous patients often believe the implant teeth are better than their experience with compromised natural teeth. The improvement over their removable restoration is significant. Some completely edentulous patients require a fixed restoration because their oral condition makes the fabrication of teeth difficult if a superstructure and RP are planned. For example, when a patient has abundant bone and implants have already been placed, the lack of crown height space may not permit an RP.

Fixed prostheses often last longer and have fewer complications than overdentures because attachments do not require replacement, and acrylic denture teeth wear faster than porcelain to metal.4 In addition, the chance of food entrapment under a removable overdenture is often greater than for a fixed restoration because soft tissue extensions and support are often required in the latter.

The completely implant-supported overdenture requires the same number of implants as a fixed implant restoration. Thus, the cost of implant surgery may be similar for fixed or removable restorations. The laboratory fees for a fixed hybrid prosthesis may be similar to those for an overdenture bar, copings, attachments, and overdenture. Yet because the denture or partial denture fees are much less than FPs, many clinicians charge the patient a much lower fee for removable overdentures on implants. However, chair time and laboratory fees are often similar for fixed or removable restorations that are completely implant supported. As a result, one should consider increasing the patient fees for overdentures to a level more in line with fixed restorations (Box 9-2).

Most often, treatment plans for completely edentulous patients consist of a maxillary denture and a mandibular overdenture with two implants. However, in the long term, this treatment option may prove a disservice to the patient. The lack of posterior implant support in the mandible will allow posterior bone loss to continue.5 Paresthesia, facial changes, and reduced posterior occlusion to the maxillary prosthesis are to be expected. As a consequence, the upper denture becomes less stable. In addition, the maxillary arch will continue to lose bone, and the bone loss may even be accelerated in the premaxilla (Box 9-3).6,7 When this available bone dimension is lost, the patient will have more difficulty with retention and stability of the restoration in either arch. The doctor should diagnose the amount of bone loss and its consequences on facial esthetics, function, and psychological and overall health. Patients should be made aware of future compromises in bone loss and its associated problems with minimal treatment options, which do not address the continued loss of bone in regions where implants are not inserted.

It is even more important to visualize the final restoration at the onset with a fixed-implant restoration. After this first important step, the individual areas of ideal or key abutment support are determined to assess whether it is possible to place the implants to support the intended prosthesis. The patient’s force factors and bone density in the region of implant support are then evaluated. The additional implants to support the expected forces on the prosthesis designed may then be determined, with implant size and design selected to match force and area conditions. Only then is the available bone evaluated to assess whether it is possible to place the implants to support the intended prosthesis. In inadequate bone or implant abutment situations, the existing oral conditions must be improved or the needs and desires of the patient must be reduced. In other words, either the mouth must be modified by augmentation to place implants in the correct anatomical positions or the mind of the patient must be modified to accept a different prosthesis type and its limitations.

Partially Edentulous Prosthesis Design

A common axiom in traditional prosthodontics for partial edentulism is to provide a fixed partial denture whenever applicable.8,9 The fewer natural teeth missing, the better the indication for a fixed partial denture. This axiom also applies to implant prostheses in partially edentulous patients.10 Ideally, the fixed partial denture is completely implant supported rather than joining implants to teeth.11 This concept leads to the use of more implants in the treatment plan. Although this may be a cost disadvantage, it is outweighed by significant intraoral health benefits. The added implants in the edentulous site result in fewer pontics, more retentive units in the restoration, and less stress to the supporting bone. As a result, complications are reduced, and implant and prosthesis longevity are increased.

Prosthetic Options

In 1989, Misch proposed five prosthetic options for implant dentistry12 (Table 9-1). The first three options are FPs. These three options may replace partial (one tooth or several) or total dentitions and may be cemented or screw retained. They are used to communicate the appearance of the final prosthesis to all of the implant team members, including the laboratory and patient. These options depend on the amount of hard and soft tissue structures replaced and the aspects of the prosthesis in the esthetic zone. Common to all fixed options is the inability of the patient to remove the prosthesis. Two types of final implant restorations are RPs; they depend on the amount of implant support, retention, and stability, not the appearance of the prosthesis.

TABLE 9-1

Prosthodontic Classification

| Type | Definition |

| FP-1 | Fixed prosthesis; replaces only the crown; looks like a natural tooth |

| FP-2 | Fixed prosthesis; replaces the crown and a portion of the root; crown contour appears normal in the occlusal half but is elongated or hypercontoured in the gingival half |

| FP-3 | Fixed prosthesis; replaces missing crowns and gingival color and a portion of the edentulous site; prosthesis most often uses denture teeth and acrylic gingiva but may be porcelain to metal |

| RP-4 | Removable prosthesis; overdenture supported completely by implants (usually with a superstructure bar) |

| RP-5 | Removable prosthesis; overdenture supported by both soft tissue and implants (may or may not have a superstructure bar |

From Misch CE: Bone classification training keys, Dent Today 8:39-44, 1989.

Fixed Prostheses

FP-1

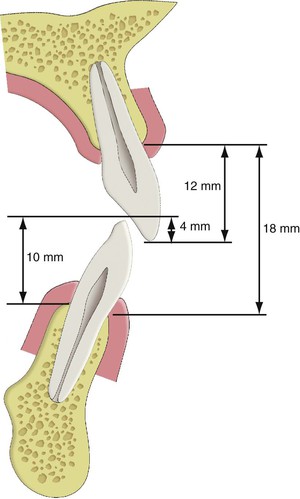

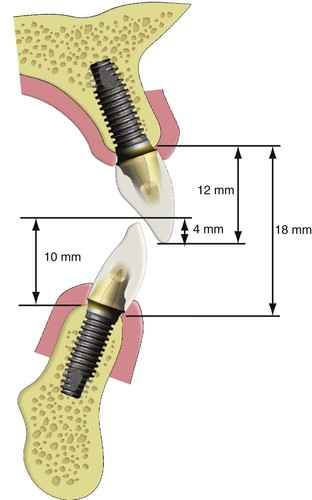

An FP-1 is a fixed restoration and appears to the patient to replace only the anatomical crowns of the missing natural teeth. To fabricate this restoration type, there must be minimal loss of hard and soft tissues (Figure 9-2). The volume and position of the residual bone must permit ideal placement of the implant in a location similar to the root of a natural tooth (Figure 9-3). The final restoration appears very similar in size and contour to most traditional FPs used to restore or replace natural crowns of teeth.

The FP-1 prosthesis is most often desired in the maxillary anterior region, especially in the esthetic zone during smiling (Figure 9-4), The final FP-1 restoration appears to the patient to be similar to a crown on a natural tooth. However, the implant abutment can rarely be treated exactly as a natural tooth prepared for a full crown. The cervical diameter of a natural tooth is approximately 6.5 to 10.5 mm with an oval to triangular cross-section. However, the implant abutment is usually 4 to 5 mm in diameter and round in cross-section. In addition, the placement of the implant rarely corresponds exactly to the crown–root position of the original tooth. The thin labial bone lying over the facial aspect of a maxillary anterior root remodels after tooth loss and the crest width shifts to the palate, decreasing 40% within the first 2 years.

The occlusal table of the crown should also be modified in unesthetic regio/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses