9 Pigmented Lesions

Exogenous Pigmentation

Amalgam Tattoo

Clinical Features

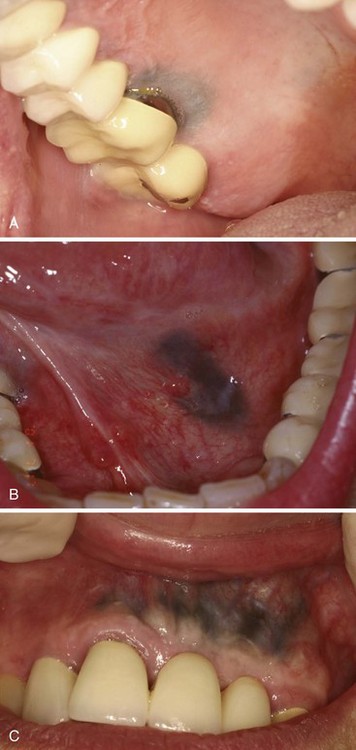

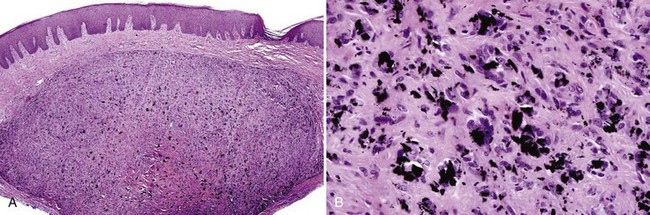

• Amalgam tattoo is localized (usually < 1 cm) or, less commonly, diffuse; it is a slate-gray macule of oral mucosa and is nontender and evenly pigmented.

• Tattoo often appears on gingiva adjacent to amalgam restorations or crowns, but it may be on any surface and, in particular, after apicoectomy (root apex surgery) with amalgam retrofill (Fig. 9-1, A-C).

Etiopathogenesis and Histopathologic Features

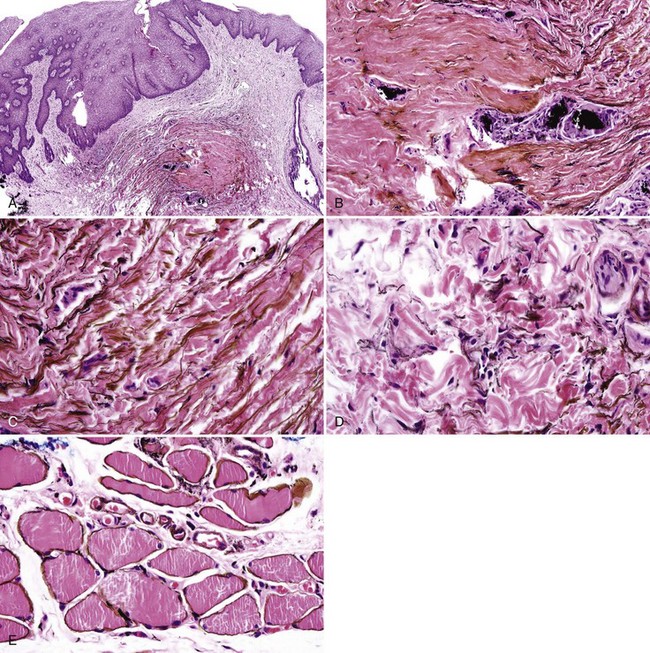

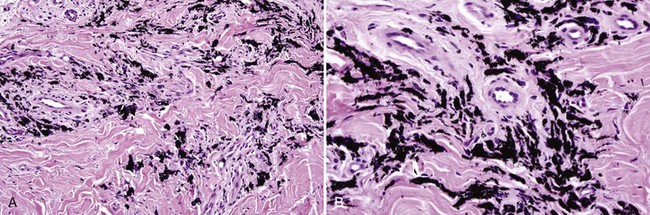

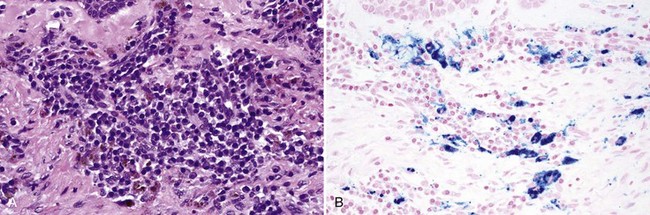

• Scar is often present (especially if lesion is not adjacent to an amalgam) with variable lymphocytic infiltrate (Fig. 9-2, A).

• Fine golden-brown particles are deposited in a “beaded” pattern along connective tissue fibers and basement membrane of epithelium and blood vessels.

• Reticulin fibers, endomysium, and endoneurium may be stained golden-brown with no particulate deposits; larger particles often are found within foreign body granulomas (see Fig. 9-2, B-E; Figs. 9-3 and 9-4).

• Refractile crystalline foreign material may be seen occasionally in traumatically implanted lesions; this likely represents fragments of dental cement placed with amalgams.

Buchner A. Amalgam tattoo (amalgam pigmentation) of the oral mucosa: clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment. Refuat Hapeh Vehashinayim. 2004;21:25-28. 92

Buchner A, Hansen LS. Amalgam pigmentation (amalgam tattoo) of the oral mucosa. A clinicopathologic study of 268 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1980;49:139-147.

Kanzaki T, Eto H, Miyazawa S. Electron microscopic x-ray microanalysis of metals deposited in oral mucosa. J Dermatol. 1992;19:487-492.

Lau JC, Jackson-Boeters L, Daley TD, et al. Metallothionein in human gingival amalgam tattoos. Arch Oral Biol. 2001;46:1015-1020.

Graphite Tattoo

Etiopathogenesis and Histopathologic Features

This is caused by traumatic implantation of pencil graphite.

Differential Diagnosis

• Unlike amalgam, it is slightly birefringent, maintains birefringence after treatment with 10% ammonium sulfide, and does not stain connective tissue fibers.

• Other traumatically-implanted foreign bodies should be considered, and the diagnosis should be elicited by a careful history taking (Fig. 9-6).

Daley TD, Gibson D. Practical applications of energy dispersive x-ray microanalysis in diagnostic oral pathology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;69:339-344.

Peters E, Gardner DG. A method of distinguishing between amalgam and graphite in tissue. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986;62:73-76.

Phillips GE, John V. Use of a subepithelial connective tissue graft to treat an area pigmented with graphite. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1572-1575.

Medication-Induced Pigmentation

Clinical Findings

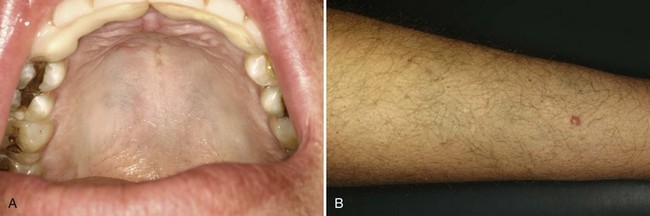

• Diffuse, painless, symmetric, bluish-gray macular pigmentation of the hard palate; patient may have concomitant skin lesions (Fig. 9-7).

• Patient on minocycline, antimalarial medications (such as mepacrine or quinacrine), birth control pills, clofazimine, and imatinib are susceptible.

• Tetracycline and its analogues are taken up by teeth and bone, which appear brown, and this is visible through the oral mucosa.

Etiopathogenesis and Histopathologic Features

Condition is caused by break-down products of the medication that chelate with iron or melanin.

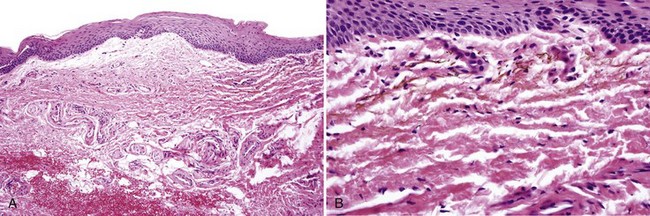

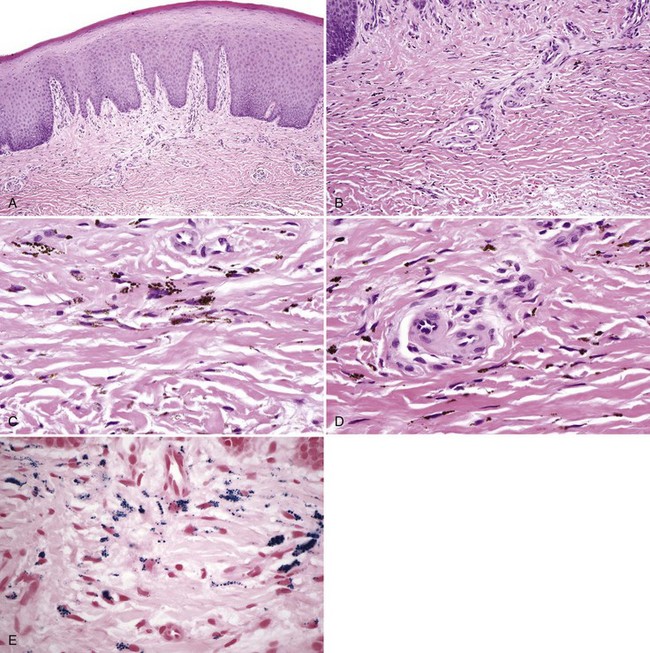

• Particles are brown, spherical, uniform, only a few microns in diameter, and they tend to align in linear fashion between collagen fibers, although this may represent pigment within dendritic processes of macrophages; particles are often present within macrophages (Fig. 9-8, A-D).

• Staining is positive with Prussian blue for iron and Fontana-Masson for melanin, although degree of staining is variable (see Fig. 9-8, E); usually elicits no fibrosis or inflammation.

• Teeth are stained by tetracycline fluoresce under polarized light.

Differential Diagnosis

• Amalgam is not spherical, and it stains the collagen fibers.

• Hemosiderin particles are larger, coarser, and more variable in size and stain with Prussian blue stain (Fig 9-9).

• Melanin is not as uniform, and it is often present concomitantly within basal cells.

• Rare instances of pigmentation caused by leaching of metals from a denture have been reported.

Cale AE, Freedman PD, Lumerman H. Pigmentation of the jawbones and teeth secondary to minocycline hydrochloride therapy. J Periodontol. 1988;59:112-114.

Kleinegger CL, Hammond HL, Finkelstein MW. Oral mucosal hyperpigmentation secondary to antimalarial drug therapy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:189-194.

Lerman MA, Karimbux N, Guze KA, Woo SB. Pigmentation of the hard palate. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107:8-12.

Mattsson U, Halbritter S, Morner Serikoff E, et al. Oral pigmentation in the hard palate associated with imatinib mesylate therapy: a report of three cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111:e12-16.

Sloan P, Kujan O. Re: Martin TJM, Sharp I. Oral mucosal pigmentation secondary to treatment with mepacrine, with sparing of the denture bearing area. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;42:351-353. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;43:268

Treister NS, Magalnick D, Woo SB. Oral mucosal pigmentation secondary to minocycline therapy: report of two cases and a review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;97:718-725.

Melanocytic Pigmentation

Physiologic pigmentation is very common on the gingiva and other mucosa of dark-skinned individuals and is generally bilaterally symmetric and evenly pigmented (Fig. 9-10, A).

Oral Melanotic Macule

Clinical Findings

• Macules are seen in adults, usually in the fifth decade, but rarely, they may occur congenitally on the tongue.

• Discrete, brown-to-tan-to-black, painless macules are usually evenly pigmented, less than 1 cm, usually on the lower vermilion, palate, or gingiva (see Fig. 9-10, B and C).

• The macule is most often solitary but may be multifocal, especially in the Laugier-Hunziker syndrome (with melanonychia) (see Fig. 9-10, D)

• Unlike ephelides, they do not darken with exposure to sunlight.

Etiopathogenesis and Histopathologic Features

Some melanotic macules may represent postinflammatory hypermelanosis, but others are idiopathic.

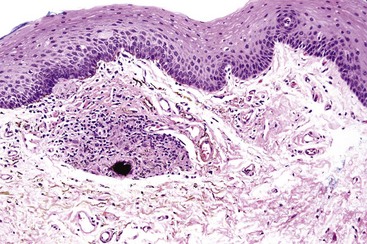

• Increased melanin occurs within basal cells in the absence of or with minimal melanocytic hyperplasia; with incontinent melanin and melanophages in lamina propria; melanin is most prominent in the lower half of the epithelium and at tips of rete ridges (Figs. 9-11 and 9-12).

• Variable vascular ectasia and absent-to-mild lymphocytic infiltrate may be evident.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses