Lymphoid Lesions

Reactive Lesions

Lymphoid Hyperplasia

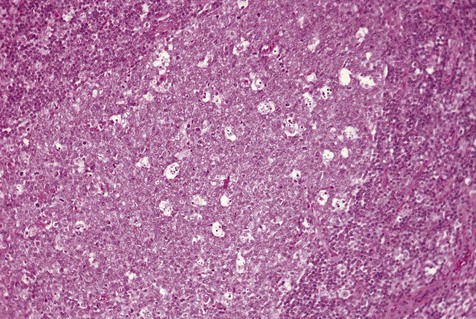

One of the normal sites of lymphoid tissue is the posterolateral portion of the tongue. Aggregations of lymphoid tissue within this area are part of the foliate papillae, or lingual tonsil. They may be distinguished from other lymphoid tissues by deep crypts lined by stratified squamous epithelium. These papillae occasionally become inflamed or irritated, with associated enlargement and tenderness. In such instances, patients may become symptomatic. On examination, these areas are enlarged and somewhat lobular in outline, with an intact overlying mucosa and prominent superficial vessels. In instances in which such lesions are removed for diagnostic purposes, the chief finding is reactive lymphoid hyperplasia. Within the enlarged germinal centers, mitoses and macrophages containing cellular debris may be seen. In addition to the foliate papillae, other zones where lymphoid tissue is found include the anterior floor of the mouth on either side of the lingual frenum, the anterior tonsillar pillar, and the posterior portion of the soft palate (Figures 9-1 and 9-2). Because lymphoid tissues are not always found in these areas, they are usually regarded as ectopic. The term oral tonsil also refers to this tissue.

Developmental Lesions

Lymphoepithelial Cyst

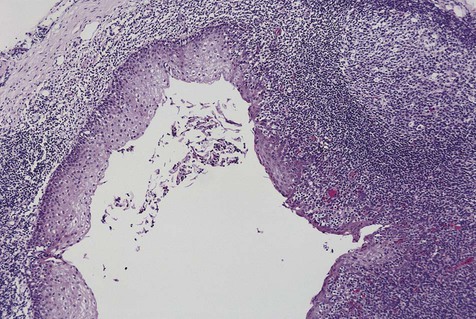

Oral lymphoepithelial cysts (see also the discussion on ectopic lymphoid tissue in Chapter 3) present as asymptomatic mucosal elevations that are well defined and yellowish pink (Figure 9-3). The site most commonly affected is the floor of the mouth, where approximately 50% of cases are found. Ventral and posterolateral portions of the tongue constitute an additional 40% of cases; the balance is shared among the soft palate, the mucobuccal fold, and anterior facial pillars. A wide age range is noted, from adolescence to the seventh decade of life. The gender distribution is essentially equal. Except for the small central cystic space, these lesions are identical to ectopic lymphoid aggregates.

Histopathology

The lymphoepithelial cyst is lined by stratified squamous epithelium that often is parakeratotic. Focal areas of pseudostratified columnar cells or mucous cells may be present. The epithelial lining is surrounded by a discrete, well-circumscribed lymphoid component, often with germinal center formation and a sharply defined zone of mantle lymphocytes. In addition, the cyst wall may contain variable proportions of lymphocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells, with occasional multinucleated giant T cells (Figure 9-4). Continuity of the cyst lining with the surface oral epithelium may be noted occasionally.

Neoplasms

Lymphoma

Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

Classification

The microscopic classification of NHL continues to evolve. At least eight classifications have been proposed over the past 30 years, but none have gained universal acceptance. The current and most widely adopted system is that from the World Health Organization (WHO) (Table 9-1), which is based on a prior system known as the Revised European American Lymphoma (REAL) scheme. This scheme divides lymphomas into T- and B-cell groups and includes a number of entities that arise at extranodal sites. This system focuses on distinct biological entities defined by a combination of clinical, morphologic, immunophenotypic, and genotypic features. It has been shown to be highly reproducible and clinically relevant. Moreover, because it is a list of entities, new lymphomas can be added when they are identified and characterized. Both the WHO and REAL classification systems have been criticized for their heavy reliance on immunohistochemical phenotyping and their problematic application when clinical information is missing or limited. Moreover, because both systems provide a list of entities without biological groupings, learning the systems can be difficult.

TABLE 9-1

MODIFIED WHO CLASSIFICATION OF LYMPHOMAS

| B-Cell Neoplasms | T-Cell and Postulated NK-Cell Neoplasms | |

| Precursor cell neoplasms | Precursor B-lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia | Precursor T-lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia |

| Peripheral (mature) cell neoplasms | B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (B-CLL/SLL) | T-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia |

| Lymphoplasmacytoid lymphoma | Large granular lymphocytic leukemia (T-cell or NK-cell type) | |

| Mantle cell lymphoma | Mycosis fungoides | |

| Marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (extranodal or nodal) | Peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified | |

| Splenic marginal zone B-cell lymphoma | Angioimmunoblastic lymphoma | |

| Hairy cell leukemia | Intestinal T-cell lymphoma | |

| Plasmacytoma | Adult T-cell lymphoma/leukemia | |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | Anaplastic large cell lymphoma | |

| Burkitt’s lymphoma |

Etiology

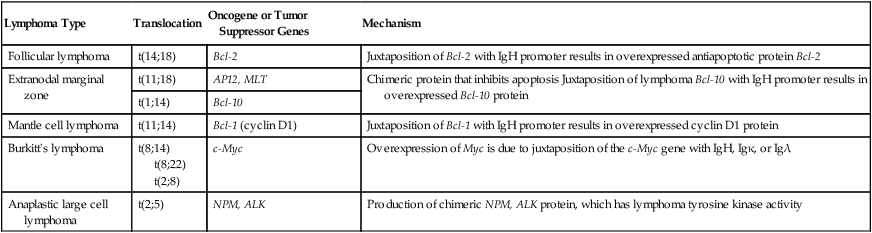

Little is known about the origin of NHL. Variations in incidence in different ethnic groups suggest a strong genetic predisposition. Immunodeficiency, whether acquired or congenital, is an important risk factor for the development of some lymphomas and may be related to a defective immune response to the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), permitting clonal expansion of infected cells. Some lymphomas are clearly associated with specific chromosome translocations such as t(8;14), t(8;22), and t(2;8) in Burkitt’s lymphoma and t(11;14) in mantle cell lymphoma (Table 9-2). These specific chromosome translocations result in the dysregulation of oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes, producing unregulated cell proliferation. Why specific translocations occur is not known.

TABLE 9-2

CHARACTERISTIC CYTOGENETIC FINDINGS IN SELECTED, SPECIFIC LYMPHOMAS

| Lymphoma Type | Translocation | Oncogene or Tumor Suppressor Genes | Mechanism |

| Follicular lymphoma | t(14;18) | Bcl-2 | Juxtaposition of Bcl-2 with IgH promoter results in overexpressed antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 |

| Extranodal marginal zone | t(11;18) | AP12, MLT | Chimeric protein that inhibits apoptosis Juxtaposition of lymphoma Bcl-10 with IgH promoter results in overexpressed Bcl-10 protein |

| t(1;14) | Bcl-10 | ||

| Mantle cell lymphoma | t(11;14) | Bcl-1 (cyclin D1) | Juxtaposition of Bcl-1 with IgH promoter results in overexpressed cyclin D1 protein |

| Burkitt’s lymphoma | t(8;14) t(8;22) t(2;8) |

c-Myc | Overexpression of Myc is due to juxtaposition of the c-Myc gene with IgH, Igκ, or Igλ |

| Anaplastic large cell lymphoma | t(2;5) | NPM, ALK | Production of chimeric NPM, ALK protein, which has lymphoma tyrosine kinase activity |

Staging

The importance of proper staging (determining the clinical extent of disease) for patients with lymphoma in the oral region cannot be overemphasized. Staging serves a number of important purposes, including determination of the type and intensity of therapy, the overall prognosis for the patient, and potential complications associated with the disease. The Ann Arbor method, although initially designed to stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma, is now widely used for NHL (Box 9-1). Generally, patients are assigned a stage between I and IV depending on the site and extent of their tumor. In addition, patients are classified as “A” (no symptoms) or “B” (constitutional symptoms).

Clinical Features

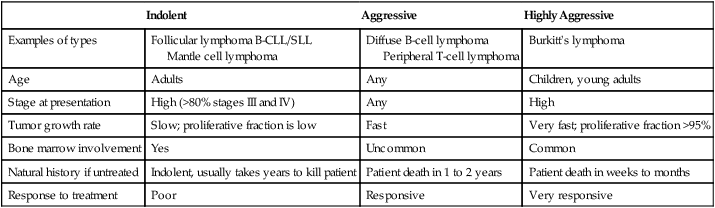

Clinically, three broad groups of NHLs can be discerned on the basis of biological behavior (Table 9-3). These lymphomas may be indolent, aggressive, or highly aggressive. Indolent lymphomas are characterized by slow growth, wide dissemination at presentation, a long natural history, and relative incurability. By contrast, aggressive and highly aggressive groups are characterized by rapid growth, frequent localized presentation, a short natural history, and frequent responsiveness to chemotherapeutic agents. Paradoxically, the most aggressive lymphomas are the ones most likely to be cured. Most lymphomas in adults are diffuse B-cell lymphoma or follicular lymphomas, which together make up more than 50% of all types. Follicular lymphoma is predominantly a tumor of lymph nodes and rarely occurs in the oral cavity. By contrast, T-cell lymphomas are considerably less common at all sites, including the oral cavity. In children, aggressive and highly aggressive lymphomas are the most common, with Burkitt’s lymphoma accounting for more than 40% of types.

TABLE 9-3

COMPARISON OF FEATURES OF INDOLENT, AGGRESSIVE, AND HIGHLY AGGRESSIVE LYMPHOMAS

| Indolent | Aggressive | Highly Aggressive | |

| Examples of types | Follicular lymphoma B-CLL/SLL Mantle cell lymphoma |

Diffuse B-cell lymphoma Peripheral T-cell lymphoma |

Burkitt’s lymphoma |

| Age | Adults | Any | Children, young adults |

| Stage at presentation | High (>80% stages III and IV) | Any | High |

| Tumor growth rate | Slow; proliferative fraction is low | Fast | Very fast; proliferative fraction >95% |

| Bone marrow involvement | Yes | Uncommon | Common |

| Natural history if untreated | Indolent, usually takes years to kill patient | Patient death in 1 to 2 years | Patient death in weeks to months |

| Response to treatment | Poor | Responsive | Very responsive |

B-CLL/SLL, B-Cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma.

Modified from Chan JKC: Chapter 21. In Fletcher CDM: Diagnostic histopathology of tumors, ed 2, London, 2000, Churchill Livingstone.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses