Chapter 9

Localised Gingival Recession

Aim

This chapter aims to outline the principal causes of localised gingival recession, including those associated with underlying systemic disease.

Outcome

At the end of this chapter the reader will be aware of the limited range of conditions that give rise to localised gingival recession and be able to recognise when referral may be prudent. Table 9-1 lists the causes of localised gingival recession. Some of these conditions are common and are best managed in the primary care sector, whilst others are less common and patients should be referred for further investigation and specialist therapy.

| Condition | Sub Category Nature | Incidence | Manage/Refer |

| Developmental defects | Dehiscence | common | manage/refer |

| Fenestration | common | manage/refer | |

| Anatomical tooth position | common | manage/refer | |

| Traumatic defects | Class II division 2 incisor relationship and gingival stripping | common | refer |

| Conscious self-induced mutilation (gingivitis artefacta) | rare | refer | |

| Subconscious self-induced mutilation | rare | manage | |

| Inflammatory defects | Localised aggressive periodontitis |

common | manage/refer |

| Peridontal-endodontic lesions | common | manage | |

| Localised chronic periodontitis |

common | manage | |

| Defects associated with underlying systematic disease | Linear Morphoea | uncommon | refer |

| Histiocytosis X | uncommon | refer | |

| Necrotising periodontitis (HIV) |

uncommon | refer | |

| Necrotising stomatitis (HIV) |

uncommon | refer | |

| Drug-induced lesions | Cocaine | uncommon | refer |

| Aspirin | uncommon | manage |

Classification of Localised Recession Defects

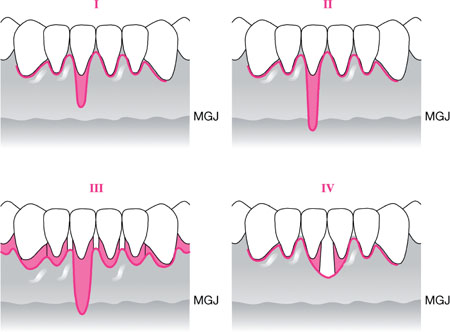

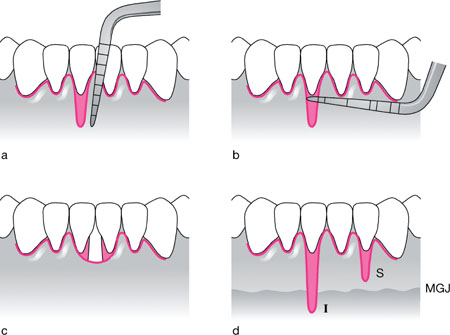

There have been several proposed classification systems to enable clinical documentation of local recession defects. Whilst not the most appropriate for diagnostic purposes, the most frequently used system is currently that proposed by Miller (Fig 9-1). This system was designed primarily to indicate the likelihood of successful management using periodontal plastic surgery procedures to correct recession defects. A practical and novel diagnostic recording system based upon clinical measurements is proposed below:

-

Measurement of the length of the recession in mm from the CEJ to the base of the defect (L1, L2 for 1mm, 2mm etc – Fig 9-2a)

-

Measurement of the width of the defect in mm at its widest aspect mesiodistally (W1, W2 for 1mm, 2mm etc – Fig 9-2b)

-

Specification of the number of teeth involved (T1, T2 etc – Fig 9-2c)

-

Identification of whether the extent of the defect is superior (S) or inferior (I) to the mucogingival junction (MGJ – Fig 9-2d).

Fig 9-1 Miller’s classification of recession defects. I – Marginal tissue recession not extending to MGJ. No loss of interdental bone or soft tissue. II – Marginal tissue recession extends to or beyond MGJ. No loss of interdental bone or soft tissue. III – Marginal tissue recession extends to or beyond MGJ. Loss of interdental bone or soft tissue is apical to the CEJ, but coronal to the apical extent of the marginal tissue recession. IV – As for III but loss of interdental bone or soft tissue is apical to the CEJ and extends to a level beyond the apical-most extent of marginal tissue recession.

Fig 9-2 Proposed diagnostic coding/notation system for recording recession defects.

Therefore, in Fig 9-3 the defect at LR1 would be annotated as L5/W2/T1/I and at LL1 as L3/W2/T1/S.

Fig 9-3 Recession defect (Stillman’s cleft) affecting LR1 (L4/W2/T1/I) and LL1 (L3/W2/T1/S). Had the interdental papilla been missing between LR1 and LL1, the defect class would have been L4/W6/T2/I .

Developmental Conditions

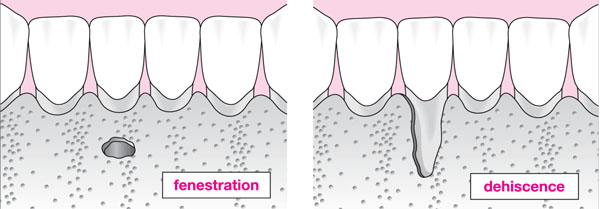

Dehiscence and Fenestration

Two classical developmental anomalies can predispose to localised recession defects sometimes referred to as ‘Stillman’s clefts’ (Fig 9-3). These are illustrated in Fig 9-4:

-

Dehiscence – the absence of a ‘window’ of bone at the facial or oral surface of a tooth (normally buccal/labial plate), i.e. the alveolar margin remains intact.

-

Fenestration – a ‘V’-shaped defect involving the alveolar margin and extending apically.

Fig 9-4 Schematic diagram illustrating a bony fenestration and dehiscence affecting LR1.

A significant amount of the blood supply to the gingivae arrives via the periosteum and an absence of periosteal blood supply renders the gingival marginal tissue less able to resist trauma and recurrent inflammation (plaque-induced), without loss of marginal epithelium and subsequent recession. The teeth most commonly affected are lower incisors and upper canines. Contrary to popular belief, there is no evidence for a direct effect from ‘fraenal pull’ as the fraenum rarely carries muscle fibres (Watts 2000). However, the fraenum may interfere with plaque control around lower incisors where the labial bone plate is thin, or there is an underlying anatomical bone defect. Prominent fraena may therefore contribute to the development of recession following repeated episodes of gingival inflammation, secondary to an inability to maintain plaque control in the area.

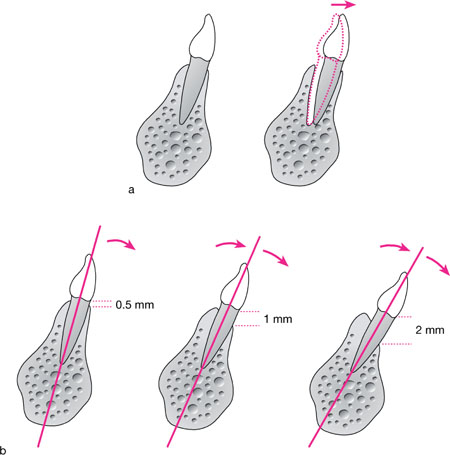

Anatomical Tooth Position

On occasions the lower incisors develop in a position that is more labial than ‘ideal’ and/or are also proclined, further reducing the thickness of labial crestal bone, or indeed its coronal extent (Fig 9-5). The overlying gingivae appear extremely thin and delicate (Fig 9-6) and are prone to recession if marginal plaque control is less than ideal.

Fig 9-5 a) Incisors positioned labially within the alveolus relative to the ideal, thereby leaving a thin labial bone plate. b) Incisors proclined in a compensatory manner in a patient with a mild class II skeletal base, thereby reducing the overbite and compromising the integrity of the labial crestal bone.

Fig 9-6 Delicate tissue biotype prone to recession due to plaque-induced inflammation and toothbrush trauma.

Traumatic Defects

Class II division 1 or 2 incisor relationship with gingival stripping.

Clinical appearance

Gingival stripping may arise in a Class II division 1 or 2 incisor relationship. Akerly classified such incisor relationships from an orthodontic perspective (Box 9-1) but in periodontal terms, Akerly Class II and III relationships are the most significant and very difficult to manage (see Heasman, Preshaw and Robertson 2004). Localised recession defects affecting one or all of the incisor teeth may be evident:

-

palatally to the upper incisors and caused by a traumatic overbite of the lower incisor edges against the palatal gingival margins (Fig 9-7). This may arise in a class II division 1 incisor relationship, where the overjet is increased and the overbite is complete, or in a class II division 2 incisor relationship with a complete overbite.

-

labially to the lower incisors and caused by the incisal edges of the upper anterior teeth occluding against the labial gingival margin (Fig 9-8). This arises in a class II division 2-incisor relationship.

Box 9-1 The Akerly classification of traumatic incisal relationships. Taken from Heasman, Preshaw and Robertson, 2004.

Class 1 Lower incisors impinge on the palatal mucosa, posterior to the palatal gingival margins of the maxillary anterior teeth. Class II Lower incisors occlude onto the palatal gingival margins of the maxillary anterior teeth. Class III A deep traumatic overbite (Class II div 2 incisor relationship) with shearing of the mandibular labial gingivae. Class IV Lower incisors occlude with the palatal surfaces of the upper incisors, leading to tooth wear by attrition.

Fig 9-7 A Class II division 2 incisor relationship with trauma to the lower labial gingivae (see blanching of lower gingival margins) (Akerly Class III).

Fig 9-8 A Class II division 2 incisor relationship with trauma to the palatal gingivae of the maxillary incisors (Akerley Class II).

Clinical symptoms

-

Pain on eating/incising.

-

Soreness/ulceration of the gingival margin.

-

Recession.

-

Aesthetic concerns related to the anterior tooth position or more generally the malocclusion (especially if there is a large skeletal component).

Aetiology

-

Unstable incisor relationship due to skeletal relationship of mandible to maxilla or habitual (thumb sucking), resulting in retroclination of lower incisors and proclination of uppers.

-

Unstable incisor relationship due to loss of periodontal support (periodontal disease) and incisor tooth movement or over-eruption (Fig 9-9).

Fig 9-9 Radiograph demonstrating over-eruption of UL 1 post-periodontal bone loss and a crescentic pattern of bone loss indicative of occlusal trauma.

Involvement of non-gingival sites

None.

Differential diagnosis

None. The key diagnostic decision is whether there is historical or currently active periodontitis.

Clinical investigation

-

Study models to examine the incisor relationship (Fig 9-10).

-

Radiographs.

-

Orthodontic opinion.

-

Incisor set up on models for orthodontic realignment, as a diagnostic procedure.

-

Incisor set up (Kesling set up) for a restorative solution (e.g. ‘Dahl’ appliance – see Noble, Kellet and Chapple 2004).

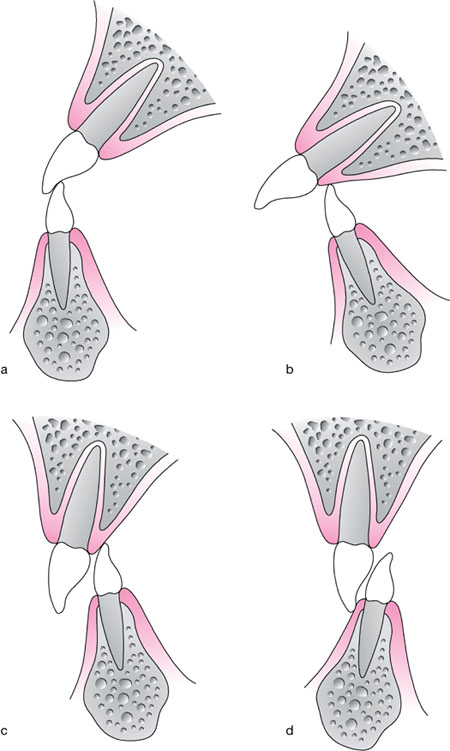

Fig 9-10 Schematic representation of a) a ‘stable’ incisor relationship, with the incisal edge of the lower teeth against the palatal cingulum rest of the upper incisors; b) an unstable Class II div 1 relationship with trauma to the palatal gingival margins; c) an unstable Class II div 2 relationship with trauma to the palatal gingival margins; d) an unstable Class II div 2 relationship with trauma to the labial mandibular gingival margins.

Management options

-

Establishing a stable incisor relationship by orthodontic means is the ideal solution, but frequently requires lengthy therapy and permanent retention, either fixed (Fig-9-11) or removable (Fig 9-12).

-

A ‘Dahl’ appliance may be of valu/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses