Chapter 9

Extraction of Unerupted or Partly Erupted Teeth

- Diagnosis

- Treatment

- Extraction of the impacted lower third molar

- Extraction of the upper third molar tooth

- Extraction of the unerupted maxillary canine

- Extraction of maxillary supernumerary teeth

- Other unerupted teeth

Teeth fail to erupt for many reasons. Evolutionary and hereditary factors that result in a disproportion in size between teeth and jaws are important. Local causes include retention or premature loss of a deciduous predecessor, the presence of supernumerary teeth, abnormal position of or injury to the tooth germ. Tumours and cysts may also prevent teeth from erupting. Certain conditions such as cleft palate, cleidocranial dysostosis, hypopituitarism, cretinism, rickets and facial hemiatrophy predispose to delay or failure of eruption.

The teeth most commonly concerned are the mandibular and maxillary third molars, and the maxillary canine. Others not infrequently seen are the mandibular second premolar and canine, the maxillary central incisors, and supernumerary teeth in both jaws. Many unerupted teeth are impacted – that is, prevented from erupting completely by other teeth or bone. Thus the lower third molar tooth commonly impacts against the second permanent molar.

Reasons for Treatment

The majority of unerupted teeth are extracted because they give rise to symptoms of pain or become foci of infection. Other indications for removal are involvement in pathology such as cysts or tumours, evidence of causing resorption of roots of adjacent teeth and interference in lines of osteotomies or fractures. Infection is less commonly seen in patients over 30 years old. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) has published accepted guidelines for the removal of lower third molars which stress that the removal of asymptomatic unerupted teeth is not justified due to the possible sequelae of the surgery. Of particular importance is the potential damage to the inferior dental and lingual nerves. Symptomless unerupted or partly erupted teeth should be monitored at intervals to detect the development of complications as outlined above.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of unerupted teeth is based on the history, clinical examination and radiographs.

History

In the absence of infection the patient often has no complaint other than that a tooth is missing. The crown may cause a symptomless swelling under the mucosa. Where pain is thought to be a symptom from a completely buried tooth, every effort must be made to eliminate other possible causes, particularly pulpitis from another tooth.

Where infection is present, more acute symptoms supervene. Inflammation about the crown of an unerupted or partly unerupted tooth is known as pericoronitis and is particularly serious when it arises from a lower third molar owing to the tendency of the infection to spread into the neck (see Chapter 12).

Examination

The dentition is accurately charted for missing permanent teeth, retained deciduous teeth, caries and periodontal disease. Caries in a neighbouring tooth can often be the actual cause of the patient’s symptoms of pain or infection, or may influence the plan of treatment where extraction of the carious tooth may allow the unerupted one to come into the space. Vitality tests of all doubtful teeth are essential. The unerupted tooth may displace, loosen or resorb the roots of adjacent teeth against which it impacts. A cyst may form in association with the crown of the buried tooth. The mouth is examined for signs of infection such as swelling, discharge, trismus and enlarged tender lymph nodes.

Radiography

The object is to show the whole of the unerupted tooth, the size of its crown and the shape of its roots together with the direction in which they curve. The presence of hypercementosis or widening of the root particularly in the apical third is noted. In multirooted teeth the number of roots and whether they are fused or divergent is important. The position of the tooth in the jaws and its relationship to other teeth, including the degree of impaction, are an indication of the difficulty of the operation. Secondary conditions such as caries, an increase in the size of the follicle or resorption of adjacent tooth roots or of bone will all affect the treatment plan (Figure 9.1).

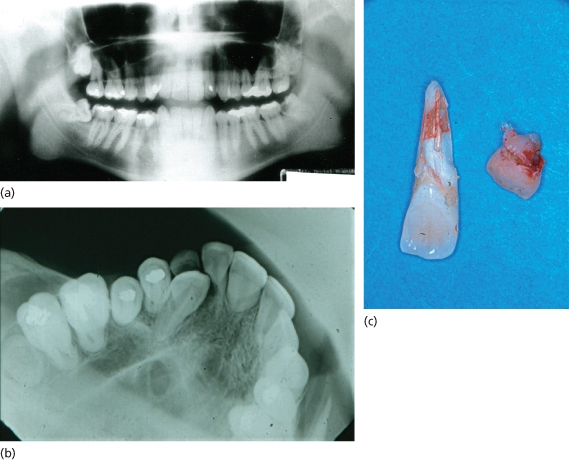

Figure 9.1 (a) Impacted third molars; caries in lower left third molar and lower right second molar; (b) impacted canine causing resorption of lateral incisor; (c) retained deciduous canine and resorbed lateral incisor.

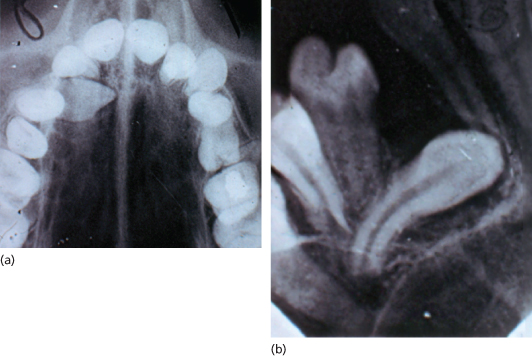

Radiographs in two planes at right angles to one another are required to show clearly the position of the tooth and the degree of impaction (Figure 9.2). The orthopantomograph (OPG) is useful as a whole mouth scan where multiple unerupted teeth may be present.

Figure 9.2 Radiographs in two planes showing position of unerupted upper right canine. Occlusal view shows crown is palatally placed.

Mandibular Teeth

In the mandible, localisation of unerupted teeth must show the whole tooth, its relationship to the inferior dental neurovascular bundle, its buccolingual position, and the relationship to adjacent teeth and the lower border of the mandible. The OPG is useful to show the position of the inferior dental neurovascular bundle and the depth of the mandible. For lower third molars this may be supplemented by an intraoral periapical film which shows more accurately the morphology of the tooth and its relationship to the second molar. To be of clinical value the radiograph must be correctly taken. The periapical film is placed with the upper border level and parallel with the occlusal plane of the second molar. The central ray is directed so that the buccal and lingual cusps of the second molar are superimposed one upon the other. The contact point between the first and second molars should be clearly shown without overlapping if the central ray has been correctly directed. This ensures that the film shows the true situation at the contact point between the third and second molar teeth, particularly how heavily the former is impacted. The distal bone over the crown of the unerupted tooth should be included. An occlusal film will show the buccolingual positions of buried teeth. It is indicated for those teeth that lie across the arch, such as premolars. It is a difficult radiograph to take for third molars.

Deeply placed teeth or those lying in the ascending ramus cannot be seen on intraoral films and if not clearly seen on the OPG, lateral oblique extraoral views may be indicated. These may also be used where there is an extensive secondary condition such as dentigerous cyst or where the mandible is very thin, as in elderly edentulous patients.

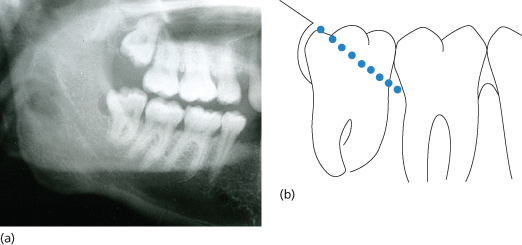

Where the crown of the third molar tooth has not obviously erupted clear of bone, it may be difficult to see on the radiographs exactly how the crown and distal bone are related. If the line of the anterior border of the ascending ramus distal to the third molar is projected to join the margin of the alveolar bone round the second molar, it will give a fair indication of the depth of overlying bone (Figure 9.3).

Figure 9.3 Projection of bone over lower third molar. The dotted line in (b) is a projection of the anterior border of the ascending ramus extended to join the margin of the alveolar bone distal to the second molar, indicating that the distal cusp of the third molar is just covered by bone.

Maxillary Teeth

Intraoral periapical and occlusal films are both used in the diagnosis of unerupted maxillary teeth. The maxillary canine may need several periapical films to cover the whole of its length and its relationship to the adjacent teeth. Its position relative to the dental arch is important as it may be placed palatally, buccally or, more rarely, across the arch. The only radiograph that will establish the true position of the canine in this respect is the vertex occlusal view taken with the central ray passing through the long axis of the incisor teeth (Figure 9.2). This film will also show how close the unerupted canine lies to these teeth and may reveal curvatures of its root not obvious on the periapical view.

Alternatively, the parallax method of Clark is used. In this, two periapical radiographs are taken with the films in the same position but with the X-ray tube moved horizontally 3 cm in a known direction between exposures (that is from 1.5 cm behind the normal centring point to 1.5 cm in front of it). Where two teeth lie in different planes the one that appears to move in the same direction as the X-ray tube lies furthest from it, that is palatally. In analysing these radiographs the relationship of the crown and the root of the buried tooth to the roots of the standing teeth must be considered separately.

The true position of the unerupted tooth in the vertical dimension is not accurately shown on a periapical film because of the angle at which the ray is directed onto the maxilla. The OPG may provide a more satisfactory answer and will show unerupted teeth high in the maxilla related to the maxillary sinus. In teeth lying buccal to the arch, a tangential view of the maxilla may be of assistance. Other unerupted maxillary teeth, supernumerary teeth and mesiodens are examined radiographically in much the same way.

Summary of Findings

From these investigations the dental surgeon should know the following facts about the patient and the unerupted tooth.

- The patient’s age, general development and the state of the dentition.

- The size and form of the crown of the unerupted tooth.

- Whether it is resorbed or, in partly erupted teeth, carious.

- The form of the roots, fused or divergent, straight or curved mesially or distally.

- The position of the tooth in the bone, whether it is lying vertically, horizontally or inverted, how deeply it is buried in bone and its buccolingual or palatal relation to the arch.

- The relationship of the tooth to other teeth and to vital structures such as nerves, the nose and the maxillary sinus.

- The size of the follicle, which may have atrophied, making extraction more difficult, undergone cystic change or have become infected.

- The texture of the bone, signs of osteosclerosis or in edentulous patients the degree of resorption of the mandible.

- The state of the adjoining teeth, whether caries, periodontal disease, apical areas or root resorption are present.

With these facts established treatment may now be considered.

Treatment

Treatment may be conservative, to bring the tooth into useful occlusion in the arch, to remove it or to leave the tooth in situ but keep it under review.

Conservative Treatment

Conservative treatment should be considered for patients where the tooth might be brought into occlusion. The advice of a specialist orthodontist is necessary as orthodontic treatment may be required prior to surgery to create space in the arch for the unerupted tooth. A conservative approach is particularly important where a neighbouring standing tooth is carious or heavily filled. In some cases eruption may not take place without exposure of the tooth and the use of traction.

Exposure of Teeth

To expose teeth a mucoperiosteal flap is made and bone is removed with burs to free the crown down to its greatest circumference. For incisors and canines the cingulum must be exposed, as must the incisal edge. Every precaution should be taken to avoid dislodging the tooth accidentally. Where the orthodontist wants a bracket, or other device to apply traction, this is placed at operation. For palatally placed teeth the soft tissues are then excised round the crown and the dead space packed with Coepack or Whitehead’s varnish on gauze. These are removed after 10 days when the patient should be referred back to the orthodontist. Care must be taken with exposure of buccally placed teeth because there is evidence that excision of the soft tissues back to non-keratinised mucosa results in an unsatisfactory epithelial cuff around the erupted tooth. Many orthodontists prefer to apply a bracket to such teeth with a gold chain or wire brought out through the wound for traction. The mucoperiosteal flap is then sutured back into position.

Transplantation

In transplantation the tooth is carefully extracted and placed in a surgically prepared socket. It is immobilised with a splint for about 4 weeks, when it is usually firm. Good results are obtained with young patients, but resorption of roots is a complication after 2–5 years and occasionally leads to loss of the tooth. Early endodontic treatment may help to prevent this. The teeth most frequently transplanted historically were unerupted maxillary canines replanted into their correct position and third molars used to replace carious first molars; however, the technique has been mostly supplanted by improved use of orthodontics to enable guided repositioning as described above.

Extraction of Unerupted Teeth

NICE has considered the removal of symptomless lower third molars and given guidelines as to when it is appropriate to remove them. The main reasons are related to pathology, e.g. pericoronitis and caries, which make the decision easier. Many other teeth are unerupted and the clinician has to make the decision as to whether it is in the patient’s best interest to leave them or remove them. Unerupted teeth can cause damage without causing symptoms and often need careful monitoring (Figure 9.1). If the decision has been made to remove an unerupted tooth this is best accomplished before it is complicated by sclerosis of bone, atrophy of the follicle, which reduces the free space round the crown, or by the presence of infection. The roots when fully formed frequently develop hooked or bulbous apices and in adults the impaction of the crown against adjoining teeth is often severe.

Ideally, the tooth is removed when the roots are two-thirds complete; before this the crown may be difficult to elevate as it tends to turn in its socket like the ball in a ball-and-socket joint. Removal of a symptomless tooth is best postponed if it is acting as a buttress for the root of an adjacent tooth, which may be simultaneously bereft of support and denuded of bone.

It is also contraindicated where vital structures such as the inferior dental nerve may be damaged in the course of the operation. In acute pericoronitis around lower third molars, surgery may have to be delayed due to difficulties in opening the mouth, but otherwise surgery will be the quickest route to relief of symptoms.

Planning the Operation

This is best done by considering first the position of the tooth in the jaw, second its natural line of withdrawal, third the obstacles to its extraction and how these may best be overcome, fourth the points of application for elevators, and finally access by removing bone and raising the flap sufficient to allow the necessary procedures to be performed.

Thus the plan is made in the reverse order to that in which the operation will be performed, as obviously the size and form of the flap depends on bone removal and this in turn is related to the position of the tooth and any manoeuvres required to disimpact it.

Natural Line of Withdrawal

This may be shown on radiographs by projecting the line along which the tooth would move if it followed the course dictated by the curvature of its roots. Teeth are most easily extracted by moving them out of their sockets or out of bone along this pathway. Where the tooth would come through the alveolus into the mouth unimpeded, except by alveolar bone, it is said to be favourably placed, but where it would go deeper into bone or impact against another tooth it is classified as unfavourable.

Extraction by moving the teeth along their line of withdrawal is done with elevators, using a gentle touch and always watching the effect of the forces applied to the tooth or roots. Heavy levering either to disimpact the tooth or lift it from its socket may have serious consequences such as fracture of the bone or displacement of the tooth into the soft tissues or the maxillary sinus. Where the roots of mandibular teeth are near the inferior dental canal, this nerve may be damaged. Resistance to elevation should be foreseen and plans made to overcome it.

Obstacles to Elevation of a Tooth

These may occur along its natural line of withdrawal and may be ‘intrinsic’, that is due to the shape of the tooth, such as hooked or bulbous apices, roots curving in opposite directions or a constriction at the neck of the tooth, all of which may anchor the tooth in bone. As many of these difficulties are found in the apical third of the root considerable bone removal may be necessary to free the tooth.

The obstacles may also be ‘extrinsic’, that is due to bone, adjacent teeth or vital structures such as the inferior den/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses