8 Salivary Conditions

8.0 INTRODUCTION

Saliva is essential for normal oral function and homeostasis. Salivary flow from the paired major (parotid, submandibular, and sublingual) and numerous minor salivary glands is controlled by the sympathetic nervous system. Functionally, saliva moistens and lubricates the surface of the tongue and other hard and soft tissues during mastication and swallowing. Immunologically, saliva plays an essential role in the control of oral infections (see chapter 7), by the actions of salivary components that include secretory IgA (sIgA), lactoferrin, lysozyme, and histatin. Saliva also has anti-caries properties (see chapter 6) demonstrated by (a) its antibacterial properties mediated through antimicrobial enzymes and sIgA; (b) its buffering capacity, which maintains a neutral pH environment; and (c) its important role in enamel remineralization by continuously bathing the teeth in calcium and phosphate ions that are reincorporated into the enamel matrix.

Any compromise in saliva production or quality can result in significant short- and long-term effects on the oral mucosa, dentition, and overall health. These changes may also secondarily alter the oral flora, creating a more “cariogenic” environment. Clinically, patients usually become aware of changes in quality and quantity of saliva when the feeling of oral dryness develops. Xerostomia, defined as the patient’s report of oral dryness, is a common complaint that may or may not correlate with salivary hypofunction, an objective finding of decreased salivary flow. Hydration status has an important impact upon salivary gland hypofunction. Systemic diseases, such as diabetes and autoimmune conditions, as well as use of several medications, have also been associated with salivary gland dysfunction (Table 8.1).

In addition to compromised function, the salivary glands are also subject to infectious, inflammatory, obstructive, and neoplastic conditions. This chapter will review the diagnosis of common salivary gland disorders.

Table 8.1 Medications associated with xerostomia.

| Class | Examples |

| Antidepressants | Duloxetine (Cymbalta), fluoxetine (Prozac) |

| Antiemetics | Ondansetron (Zofran), metoclopramide (Reglan) |

| Antihistamines | Diphenhydramine (Benadryl), fexofenadine (Allegra) |

| Antihyperlipidemics | Atorvastatin (Lipitor), simvastatin (Zocor) |

| Antimuscarinics/spasmodics | Tolterodine (Detrol), oxybutynin (Oxytrol) |

| Antipsychotics | Olanzapine (Zyprexa), lithium carbonate (Eskalith) |

| Benzodiazepines | Clonazepam (Klonopin), diazepam (Valium) |

| Diuretics | Bumetanide (Bumex), furosemide (Lasix) |

| Hypnotics | Eszopiclone (Lunesta), zolpidem (Ambien) |

| Opioid analgesic combinations | Oxycodone/acetaminophen (Percocet), hydrocodone/acetaminophen (Vicodin) |

| Muscle relaxants | Tizanidine (Zanaflex), cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril) |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | Naproxen (Aleve), etodolac (Lodine) |

| Proton pump inhibitors | Omeprazole (Prilosec), esomeprazole (Nexium) |

8.1 Implications of salivary hypofunction

8.1.1 Local infection

Patients with significant salivary gland hypofunction are at an increased risk for developing recurrent oropharyngeal candidiasis (see chapter 7) and rampant dental caries (see chapters 6 and 10). Candidiasis is frequently encountered in patients with severe salivary hypofunction, and patients with recurrent episodes may require long-term prophylactic therapy. Dental caries present most frequently at gingival margins (where food debris collects) and interproximally. For this reason, bitewing radiographs should be obtained routinely (every 6–12 months) and use of fluoride and remineralizing products should be prescribed in patients with significant salivary hypofunction.

8.1.2 Dysphagia

Decreased salivary flow may result in significant difficulties with chewing and swallowing. The moisturizing and enzymatic functions of saliva are critical for the formation of a soft bolus for deglutition. Copious amounts of fluid may be needed to aid with swallowing so that food does not lodge in the esophagus. Furthermore, patients with severe salivary hypofunction may be at risk for aspiration of food into the larynx, causing an elevated risk of airway obstruction and aspiration pneumonia. Patients with a history of recurrent episodes of dysphagia or esophageal blockage should be referred to a gastroenterologist for further evaluation.

8.1.3 Oral discomfort

Patients with salivary gland hypofunction often describe a generalized sensation of mouth discomfort due to the lack of moisture and lubrication. Persistent dryness may cause mucosal sensitivity to flavored or spicy food and drinks, and in some cases there may be a complaint of a persistent burning sensation in the absence of any recognized cause. This is a clinical symptom that should not be confused with burning mouth syndrome (see chapter 12), a condition that is defined by the absence of any underlying cause or disorder.

Table 8.2 Medications associated with taste changes.

| Class | Examples |

| ACE inhibitors | Captopril (Captopril), enalapril (Vasotec) |

| Analgesics | Acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin), nabumetone (Relafen) |

| Antibiotics | Metronidazole (Flagyl), penicillin V (Veetids) |

| Anticonvulsants | Carbamazepine (Tegretol), phenytoin (Dilantin) |

| Antidiabetics | Metformin (Glucophage), glipizide (Glocotrol) |

| Antigout | Allopurinol (Zyloprim), colchicine (Colcrys) |

| Antimanics | Lithium carbonate (Lithium), risperidone (Risperdal) |

| Antimetabolites | Methotrexate (Trexall), hydroxyurea (Hydrea) |

| Antiparkinsonians | Levodopa (Sinemet), benztropine mesylate (Cogentin) |

| Antituberculars | Ethambutol (Myambutol), isoniazid (Nydrazid) |

| Hormone replacements | Thyroxine (Synthroid), estrogen (Premarin) |

| Proton pump inhibitors | Prilosec (Omeprazole), esomeprazole (Nexium) |

8.1.4 Dysgeusia

Taste perception is a complex process mediated by sensory input to nerve endings (from cranial nerves VII, IX, and X) located in the oral mucosa, mostly on the dorsal tongue. Saliva plays a key role in transmitting taste signals, and dysgeusia (altered taste) or hypogeusia (diminished taste) may be reported by patients with low salivary flow. Abnormalities range from decreased or altered perception of certain or all tastes (sour, bitter, salty, sweet) to a complete loss of taste (ageusia). The diagnosis of dysgeusia is primarily based on patient history and is discussed in more detail in chapter 10. Importantly, some medications may cause taste abnormalities without directly affecting salivary flow, especially angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and hormone replacement therapy (Table 8.2). There is limited effective treatment for dysguesia; patients may benefit from referral to centers that specialize in taste and smell disorders.

8.2 Diagnostic tests for saliva and salivary glands

8.2.1 Measurement of xerostomia and salivary hypofunction

Xerostomia is more frequently assessed than salivary gland hypofunction, which requires objective measurement of salivary flow. Subjective and objective measures of mouth dryness are not always well correlated, and it is not uncommon for a patient complaining of xerostomia to have normal salivary flow rates. Numerous studies have demonstrated that assessment of xerostomia is a better reflection of patient symptoms and is a useful guide for management. Several instruments, such as the the Xerostomia Inventory and the Xerostomia Intensity Scale, measure the severity of mouth and lip dryness and impact on a patient’s ability to perform oral functions such as swallowing and speaking. Although these validated scales appear to be useful in assessing xerostomia severity and its impact over time, a significant limitation is the inability to actually diagnose and score xerostomia using these tools.

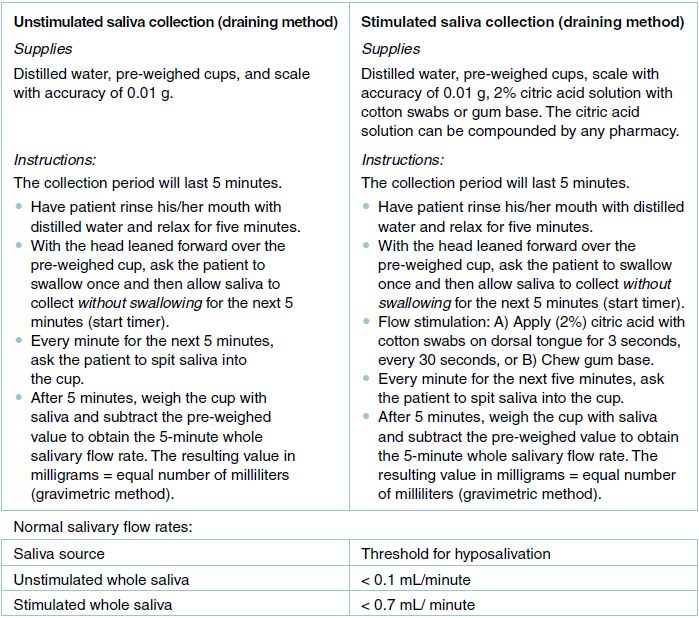

Figure 8.1 Salivary flow collection procedures and measurement protocols.

Objective assessment of salivary flow can be a useful diagnostic tool to validate symptoms of xerostomia and may be included as part of the diagnostic work-up for Sjögren syndrome. Salivary flow measurements may also be used to evaluate response to therapy. Salivary function is assessed by sialometry, in which salivary flow is measured volumetrically over an established period of time and compared to normal values. Salivary flow rates for healthy adults have been normalized using population-based data. Flow measurement can be gland-specific (parotid, submandibular/sublingual) or whole (all glands including minor glands) and can be evaluated at rest (unstimulated) or after stimulation. A normal value for whole unstimulated saliva is a volume greater than 0.1 milliliters (mL) per minute, while that for stimulated saliva is greater than 0.7 mL per minute; gland-specific standard values have not yet been established. Since flow rates may fluctuate with circadian rhythm, collection should be performed in the morning when there is less variability, and consecutive collections in the same patient should always be performed under the same conditions.

The simplest and most frequently used salivary collection technique is the draining method, in which the patient expectorates pooled saliva into a pre-weighed container (Figure 8.1). Additional methods of saliva collection are primarily used for research purposes and include mechanical draining, mechanical suction, and the use of saliva collectors. Mechanical draining is accomplished with an electric laboratory pipette placed in the floor of the mouth, removing saliva (combined submandibular/sublingual) when a “pool” of saliva accumulates (salivary pooling). Parotid flow is collected via a mechanical suction device called the Carlson-Crittenden cup, in which the suction device is placed over the Stensen duct orifice (Figure 8.2). Hydroxycellulose sponges and polyester/cortisol rolls can be placed in the mouth to absorb saliva. This method is often used for research purposes to obtain saliva for biochemical or biomarker studies.

Figure 8.2 Carlson-Crittenden collectors. Saliva drains gravimetrically to the bottom orifice (B) and through the collector to the adjacent tubing. The outer ring (A) is used to establish negative pressure on the buccal mucosa to maintain />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses