8 Rhinoplasty

An isolated chapter dedicated to rhinoplasty will certainly be only an overview and create a good basic general knowledge, but in no way can it cover the breadth of knowledge required to be an expert in rhinoplasty. Many giants in the field of rhinoplasty have dedicated entire careers to understanding this exciting procedure: Dean Toriumi, Gilbert Aiach, Jack Sheen, Jack Gunter, Eugene Tardy, Rod Rohrich, and John Tebbetts. Their multiple publications on rhinoplasty would be valuable reading for any aspiring rhinoplasty surgeon.1–7 This chapter seeks to give a basic understanding of classic rhinoplasty along with an anatomic basis for typical techniques shown in a step-by-step fashion.

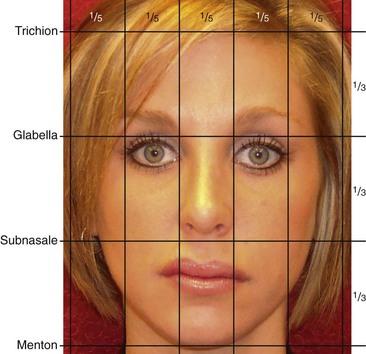

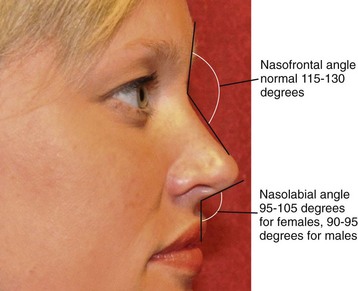

Undoubtedly, all of the great rhinoplasty surgeons would likely agree with Leonardo da Vinci who, 500 years ago, demonstrated how important facial proportion is to beauty. Nowhere is it more critical than in the middle of the face, where the proportion of the nose is absolutely critical to the success of an operation.8–10 Understanding correct proportion and how to achieve this related to all subunits of the nose and the face as a whole is an absolute necessity before taking on the nuances and details of rhinoplasty itself (Figure 8-1).

Anatomy

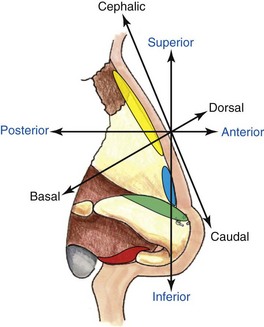

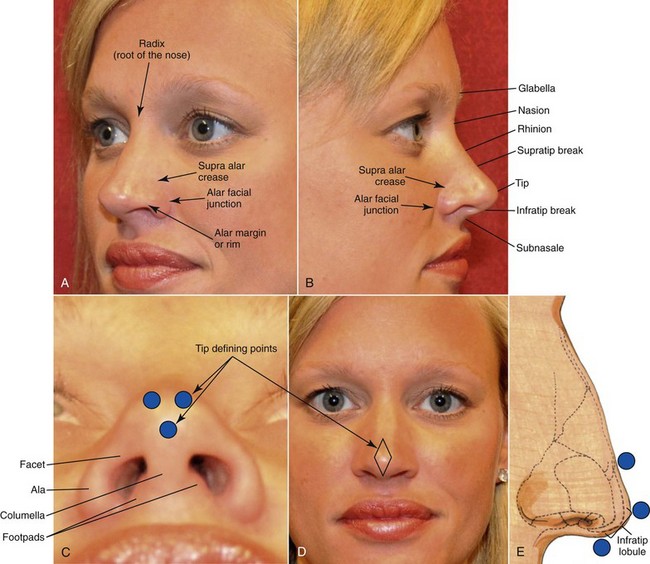

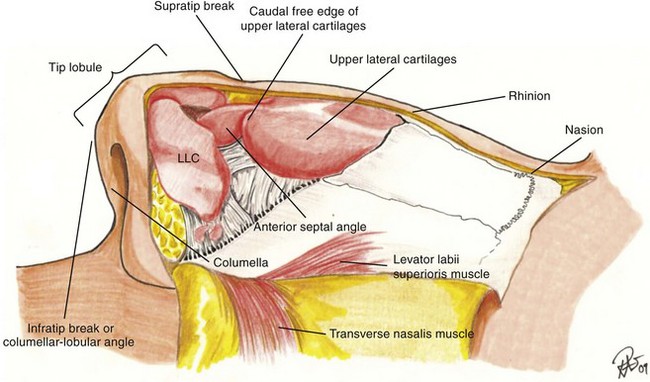

Terminology is the area that is most confusing for the novice rhinoplasty surgeon, particularly because the standard terms for direction (superior, inferior, anterior, and posterior) are used less often than the terms cephalad, caudal, and dorsal/basal (Figure 8-2). The confusion is because of the ambulation of the nose in relationship to the up-and-down position of the head, where the ease of use—particularly cephalic, dorsal, and caudal—to describe positioning during rhinoplasty surgery is more specific.11,12 Various physicians will certainly use terms interchangeably, and there are many other anatomic terms used to describe the nose that may differ among all surgeons. The terms nasal tip and nasal lobule are used interchangeably, although most would describe the nasal tip as being the most projected point of the nose that is positioned between the two domes as well as between the supratip break and infratip break points. The tip of the nose is probably the most important area because of its location and all the finer details that make up its shape (Figure 8-3). The ill-defined nose is simply one that does not have all its tip-defining points. This is also known as an amorphous nose and may be due to either ill-defined cartilage or thick skin that is hiding (camouflaging) the cartilaginous structure (Figure 8-4).

Skin thickness is an important part of the nasal anatomy that must be recognized preoperatively. Classically, the thickness of the skin differs along the dorsum compared to the rest of the nose and nasal tip.13 In the region of the root of the nose, or radix nasi, the skin is relatively thick and somewhat mobile. The thinnest skin of the nose is classically over the rhinion, which is in the mid-dorsal region and is quite mobile in this region as well. The skin then becomes thick again in the tip region, where it is most adherent and typically more sebaceous in nature. The more sebaceous nasal tip skin does not heal well from external scars. For instance, injury or an external incision on the nasal tip for removal of a mole leaves a worse scar than on areas of thin skin. Luckily, the columella has minimal sebaceous glands compared to the tip and heals nicely from an open transcolumellar rhinoplasty incision.

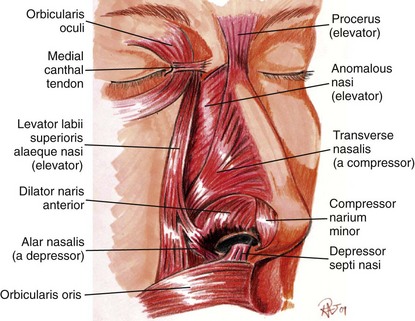

Nasal Musculature

The layer below the very thin subcutaneous level contains the muscles that involve the nose. These muscles are commonly thought of as an extension of the SMAS (superficial musculoaponeurotic system), a fibromuscular layer that involves not only the muscles of the nose but extends laterally into the other facial musculature and is commonly used laterally for face lifting. There is some argument whether or not a true SMAS exists or if it is simply a histologic diagnosis because of the thin nature of this fibrotic tissue investing the muscle. The muscles that make up the nose do function in facial expression and even help with the function of breathing and animation during smiling. The muscles can be divided into elevators, depressors, compressors, and dilators of the nose. Typically the muscles are paired and are extremely thin and much more superficial than the other muscles of the body (Figure 8-5). Because a good portion of the blood vessels course into the muscular layer, surgical dissection must be limited below the muscular layer that covers the bony and cartilaginous structures. Staying well below the nasal musculature helps prevent damage to vessels, nerves, and lymphatics. It also limits unnecessary bleeding that may lead to excessive ecchymosis, edema, and scarring.

Certain muscles do occasionally require surgical treatment. A depressor septi nasi muscle that is overactive can create a significant ptotic-type displacement of the nasal tip when the person smiles.14 Transection of this muscle is easily accomplished and can dramatically improve this deformity. Similarly, the dilators of the ala, including the ala and nasalis muscle, may occasionally be treated if excessive alar smiling is noted on high smile. In general, the nasal muscles are avoided, particularly to prevent excessive bleeding. The ideal plane for nasal dissection is below the muscular position in most cases.

Nasal Blood Supply

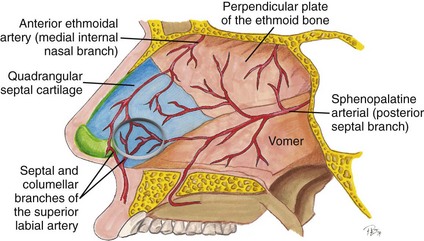

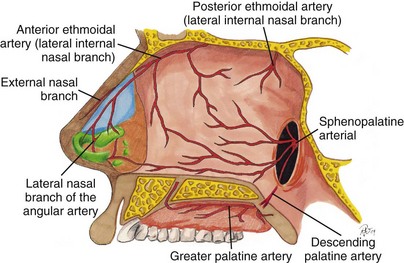

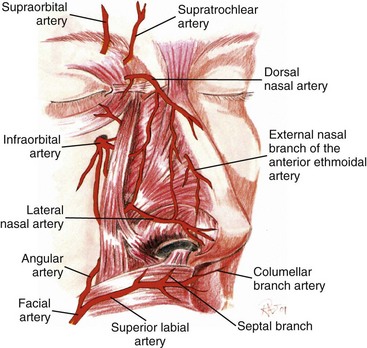

The blood supply to the nose and septum is extremely rich and comes from multiple sources.15–18 The classic interior nosebleed, for example, comes from the Kiesselbach plexus on the septum, which is an area where there is convergence of three arterial sources: one from the branch of the superior labial artery, one from the branch of the sphenopalatine artery, and the other from the anterior ethmoidal artery (Figure 8-6).

The significant blood supply to the nose comes from both internal and external carotid arteries and ultimately creates a rich subdermal vascular plexus to the external nose itself. Branches of the ethmoidal and superior labial artery extend to the nasal tip, and the lateral nasal artery conveys an even more robust blood supply to the nasal tip and allows for transection of the columella without fear of ischemia (Figures 8-7 and 8-8). Auspiciously, the significant plexus of the vessels arising from multiple sources creates a venous and lymphatic network that is largely the same. Many believe a closed rhinoplasty creates less nasal edema, although arguments can be made that there are adequate channels of lymphatic and venous drainage for open or closed rhinoplasty. Therefore, postoperative edema from rhinoplasty may be similar, since postoperative drainage should be adequate for either technique if performed carefully.

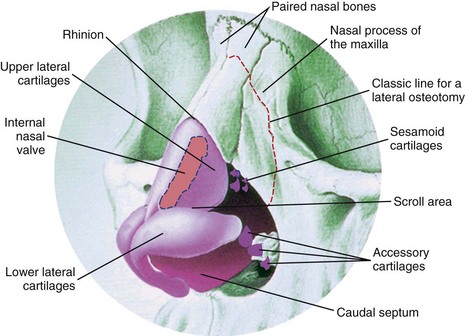

Nasal Bone and Cartilage Anatomy

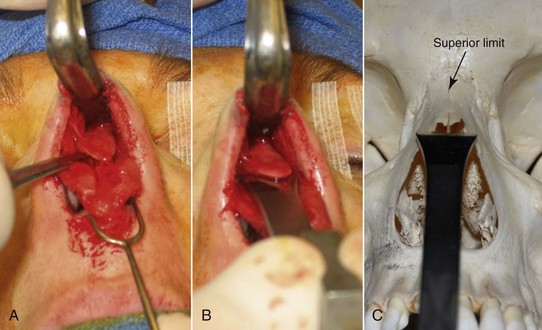

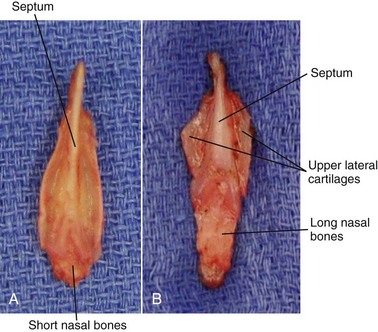

The bony vault at the nasion (nasofrontal suture) is the thickest, most solid portion of the nasal structure. It is made up by the paired nasal bones and the frontal process of the maxilla. The nasofrontal angle, the anatomic position of the junction of the frontal and nasal bones, is an important clinical landmark (Figure 8-9). The nasal bones extend various lengths caudally to connect with the upper lateral cartilage and can overlap the cartilages by several millimeters.

The nasal bones are most adherent at the root or base of the nose. The bones thin significantly as they extend caudally toward the upper lateral cartilages. This root of the nose, where the bone is thickest, is a common area for rasping to lower a nasal dorsal hump in the cephalic portion. A very large nasal dorsal hump may require the use of a Rubin or other osteotome to reduce the bony dorsum (Figures 8-10 and 8-11).

The bones of the nose are quite variable in both thickness and length. Patients with short nasal bones may be more at risk for internal nasal valve collapse, since more of the middle nasal vault will be formed by long upper lateral cartilages that make up a portion of the internal valve.19–22

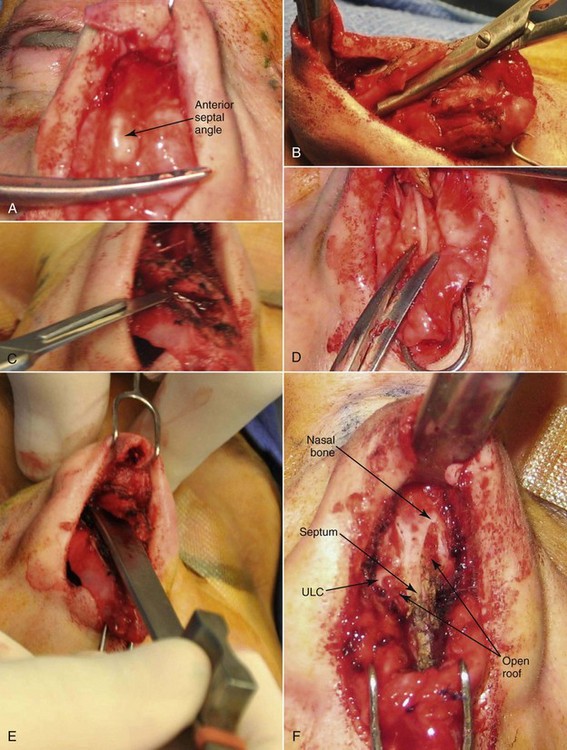

The nasal bones connect caudally to the paired upper lateral cartilages (Figure 8-12). There is a very firm attachment to the nasal bone and upper lateral cartilages, particularly along the medial edge adjacent to the septum. The upper lateral cartilages extend just over 5 mm beneath the nasal bones to allow for a firmer attachment. Extreme rasping with a coarser aggressive rasp can potentially dislodge the upper lateral cartilages from the nasal bone insertion, creating a significant deformity if unrecognized. The upper lateral cartilages provide the majority of support in the middle third of the nasal pyramid, along with the anterior border of the nasal septum. The lateral cartilages continue along the anterior border of the septum, with perichondrium covering both the superficial and deep surface.

The portion of upper lateral cartilages that connect to the nasal septum in the mid-vault region constitutes a landmark termed the internal nasal valve. This area is an extremely important region with regard to potential breathing compromise before and after rhinoplasty surgery. The action of the dilating muscles on the lateral portions of the upper and lower lateral cartilages play a role in maintaining at least a 10- to 15-degree angle of the nasal valve to maintain adequate airflow. Damage to the dilating muscles or direct damage and scarring of the valve itself can hamper breathing through the nose. Scarring in the valve from overaggressive resection of overlying lateral cartilages is the most common culprit. Patients with a classic high, narrow vault to begin with are more at risk for nasal vault problems following rhinoplasty, and this must be noted in the consultation (see Case 6). A patient with a high, narrow vault requiring significant hump reduction may require spreader grafts placed between the resected dorsal septum and upper lateral cartilages to prevent valve compromise after surgery (Figure 8-13). To avoid causing breathing or cosmetic problems from middle vault collapse, caution must always be used when resecting any portion of the upper lateral cartilages.

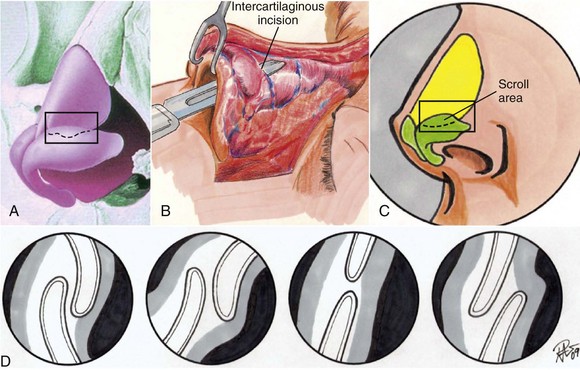

The anatomy of the lowest portion of the upper lateral cartilage can be quite variable where the upper lateral cartilages connect to the lower lateral cartilages. This area is considered the scroll region. The upper and lower lateral cartilage connection has been described by different authors. One of the most common describes the cartilages connecting by interlocked shape 52% of the time, overlapping 20% of the time, end to end 17% of the time, and opposed 11% of the time (Figure 8-14). The scroll area provides significant support to the nasal pyramid, particularly the tip.

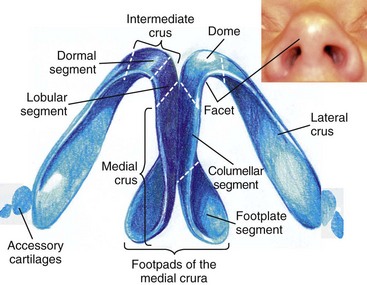

The lower lateral cartilages form the majority of the nasal tip and account for the majority of patient complaints with regard to the shape of the nose.23 The nasal bones and upper lateral cartilages create the classic nasal dorsal hump, whereas the lower lateral cartilages create the common complaint of a bulbous or boxy nose deformity. The structures of the lower lateral cartilages involve a medial, intermediate, and lateral crus. They not only affect the nasal tip appearance but help in function. The thickness and elasticity of the lower lateral cartilages play a major role in the external nasal valve and overall tip support. The lower cartilages, particularly the intermediate crus, help make up the dome (Figure 8-15).

The angulation of the lower lateral cartilages themselves can vary tremendously from patient to patient. The axis of the lateral crus can be very oblique or positioned more medially. In addition to varying positions of the axis, the cartilage can actually be concave in shape rather than the more common convex shape. Often the lateral crus will have an irregular distorted appearance simply as a congenital anomaly. The relationship of the caudal edge of the lateral crus adjacent to the anterior septal angle makes up the very important supratip region (Figure 8-16). The various morphologies of the medial, intermediate, and lateral crural cartilages can dramatically change the appearance of a nasal tip, which explains why the vast majority of grafts placed in the nose are used in this region.

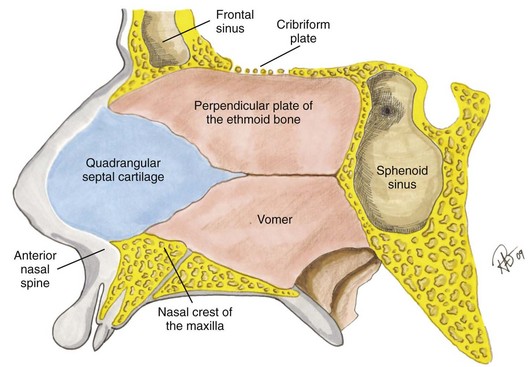

The nasal septum, which connects to all the previously mentioned structures—nasal bones, upper lateral cartilage, and lower lateral cartilage—provides significant support to the nose throughout its entire length and plays a big part in both a nasal dorsal hump and actual tip projection.24–29 Compared to the medial crural cartilages that make up a portion of the columella, the caudal septum itself is a sturdier type of cartilage and must be addressed for problems such as hanging columella and almost any other major tip-projection issue. The nasal septum is composed of bone and cartilage, the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid, the vomer, and the quadrangular cartilage (Figure 8-17). It also has a rich blood supply as previously described and can have various shapes when it connects to the maxillary crest, along with multiple deformities and deflection types. An asymmetric nose is basically impossible to treat without addressing the septum, which inevitably plays a major role in a crooked shape or asymmetries. Also, the nasal septum is one of the best sources for cartilage or bone for grafting the tip or dorsum in reconstructing defects. The classic description of cartilaginous sparing of the nasal septum has to do with leaving a 1-cm caudal and dorsal strip to provide adequate support of not only the tip but the dorsum in order to prevent tip grafts or a saddle nose deformity. While the 1-cm rule is certainly a landmark, multiple other factors play a role in the amount of septum to leave behind. Thickness of residual bones, upper and lower cartilages, and additional grafts all affect the strength of tip projection. The key is to realize that the septum has a major function in the aesthetics of rhinoplasty surgery, particularly with support of the nose, and is invaluable as a source for tissue grafting. The inferior turbinates are often a source of nasal obstruction and septal deviation and must be evaluated before and during rhinoplasty. Enlarged inferior turbinates can be treated any number of ways, including partial anterior resection or out-fracturing.30,31 Overresection has been known to create chronic problems like nasal dryness.

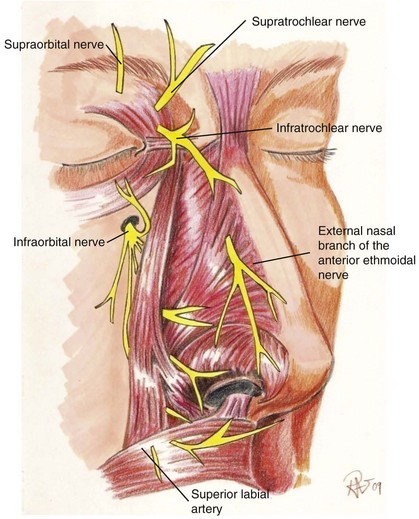

Finally, the nerve supply to the nose comes from sympathetic sensory divisions of the ophthalmic and maxillary branches of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V; Figure 8-18). Branches of the supratrochlear and infratrochlear nerves supply the upper half of the nose. The infraorbital nerve and external nasal branch of interior ethmoidal nerve supply most of the lower half of the nose.

Examination and Consultation

During the entire consultation, the patient’s mental status must be evaluated to detect evidence of possible body dysmorphic disorder or any other worries that may create problems in the postoperative period.32,33 The young male rhinoplasty patient is often one of the more challenging patients when it comes to achieving a result they will be completely happy with on a long-term basis. Classic signs of potential problems are patients who bring in magazines of movie stars with a particular shape of nose; some may be realistic, but a more in-depth evaluation of this patient must be undertaken. Ideally you hope to only operate on a patient one time, because second surgeries are always more challenging and difficult. In addition to the routine workup for medications and history of surgery, it is important to rule out any history of chronic use of nasal sprays such as Afrin or the possible history of cocaine use.

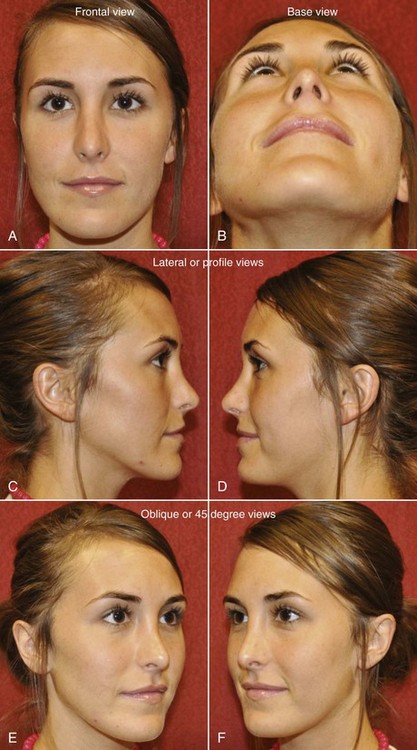

Taking photographs is an important part of record keeping that can be invaluable for treatment planning.34 Quality photographs in six standard views are needed: frontal (full face), two lateral, two 45-degree (oblique) views, and a basilar view (Figure 8-19). Other photos may occasionally be necessary, such as relaxed frontal and high-smiling frontal and lateral views to evaluate nasal tip displacement from an overactive depressor muscle. Standardization of the photographs is critical for follow-up and evaluating your own results over time. Since it may take a year or more to see the final changes that can occur after rhinoplasty, good photographs are essential.

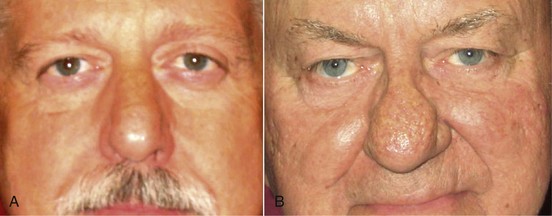

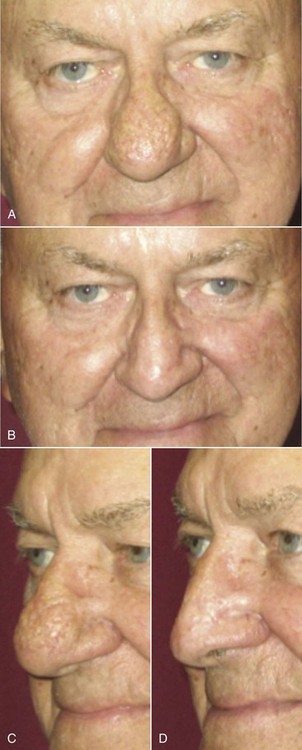

Initial assessment of skin thickness should be noted throughout the upper and lower nose, along with the amount of sebaceous-type nasal skin. Elasticity is noted by a simple pinch test and stretching the skin over the nose. Palpation, particularly in the nasal tip, is used to assess the amount of support over the nasal tip itself and gain a sense of possible irregularities that cannot be simply visualized. Thin-skinned patients have the potential for a very nicely sculpted nose but are also at risk of showing every flaw. On the other hand, patients with bulbous tips but very thick skin may not get the result they hoped for because the thick skin limits the amount of shrinkage that can safely be achieved by standard rhinoplasty. Rhinophyma, which is an overgrowth of sebaceous glands secondary to rosacea, can be treated by addressing the outer skin alone (Figure 8-20).

Proportional evaluation of the nose related to the face is critical. Classic methods that were developed by Leonardo da Vinci and others are commonly performed. For example, the width of the alar base compared to the intercanthal distance is an easy assessment and can quickly give an idea of proportion, as can simply measuring the distance and recording the base of the nose. The length of the nose is also assessed from the radix to the nasal tip and must be based on proportion to the rest of the face. In addition to nasal length, angulation from the lateral view is extremely critical, particularly in the nasal frontal and nasolabial angles. The ideal nasal frontal angle is between 115 and 130 degrees and is slightly more obtuse in females (see Figure 8-9). It can appear very different when a nasal dorsal hump is present and also from a significant amount of bossing in the glabellar and frontal region or even a deepened or shallow radix area. The depth of the radix can be assessed by evaluating the distance from the pupil to the nasion from the lateral view; it should be in the range of 4 to 9 mm on average. Reporting the amount of nasal dorsal hump or possible saddle nose deformity is important, along with whether the patient feels they have a large hump, a small hump, or none at all. The patient should be asked whether they prefer a straight nasal dorsum or like the appearance of a more “scooped” look to assess what they would ultimately be happy with. Performing computer simulation can be helpful in particular patients who may have an unrealistic expectation of what can be performed. Surgeons vary in whether they like this idea, since the actual result may not resemble the prediction. If using computer simulation, it is critical to inform the patient that this is a simulation only, the results may vary, and it is simply a tool to guide surgical planning and assess what can be realistically achieved.35 For the right patient, computer simulation can be invaluable for determining what he or she is hoping to achieve, as well as what bothers them most of all.

Nasal Tip Clinical Evaluation

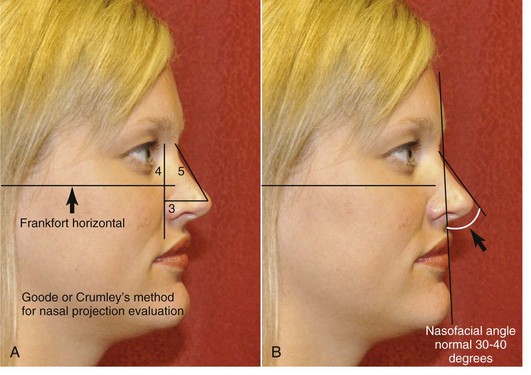

Tip projection and support are assessed based on palpability and visualization. Assessment of the nasal tip projection is difficult because occasionally the amount of projection can appear greater than what actually exists, such as in the case of a ptotic tip with a nasal dorsal hump. Often, once the other portions of the nose are addressed, the amount of projection changes. The Goode method of assessing projection is one of many, whereas RT represents the distance between the radix and the pronasale (Figure 8-21); the ideal tip projection is 0.55 to 0.60 of RT. It can also be measured from nasion to nasal tip (0.55 to 0.60 of N-NT). Another method is Crumley’s method, which is based on measurements of a nasal triangle that proportionately equals 3-4-5 based on lines perpendicular and parallel to the Frankfort horizontal (3 AP-NT, 4 N line to AP, 5 N-NT).36 Another method for assessing tip projection implies that the length of the upper lip from subnasale to labrale superius should be equal to the tip projection measured from subnasale to pronasale. In any case, the amount of projection related to the dorsum as well as from the anterior face is critical.37–45

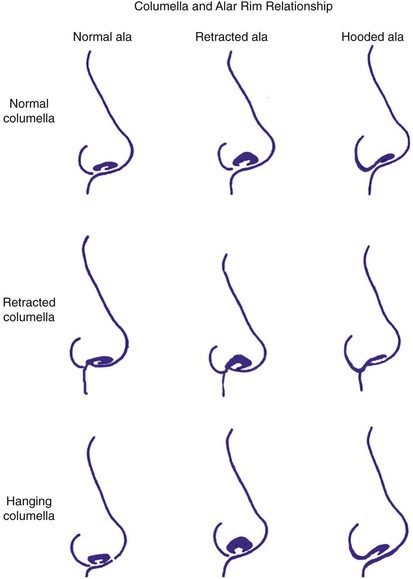

The columella must also be assessed and should ideally have 2 to 4 mm show from a lateral view. Not only should there be 2 to 4 mm of alar show from a lateral view but the ala must be evaluated simultaneously for proper position. Evidence of a hanging columella or a retracted columella should be noted when assessing true columellar show. The ala must be assessed along with the position of the anterior nasal spine and the amount of skin in the base of the columella that can be visualized directly at the nasolabial angle itself.46–51 A retracted columella can be very unaesthetic. It may be due to inadequate tissue support over the anterior nasal spine or simply an enlarged ala that gives the illusion of a retracted columella. The relation of the columella to the alar rim can be a mix of situations (Figure 8-22). The nasolabial angle is a very important measurement to note and is classically just over 90 degrees in men and 95 to 110 degrees in women. This angle can be affected by not only the amount of tip rotation and caudal septum but also by the amount of anterior nasal spine projection or even the effects of the entire maxilla and upper incisor teeth. Overzealous cartilage resection can create a nasal tip that is too short or overrotated and a nasolabial angle that is too obtuse (see Figure 8-82).

In assessing the overall projection of the nose and proceeding downward to the anterior nasal spine, it is important to evaluate the face as a whole, since problems requiring orthognathic surgery (e.g., maxillary deficiency, mandibular problems) can indirectly affect the shape and appearance of the nose.52 The combination of a nasal dorsal hump and microgenia creates proportional discrepancy a patient may want to have corrected. A patient with a weak chin or mandible often feels like their nose is unaesthetic because the total facial disharmony accentuates the often more mild nasal deformity. Often, placement of a chin implant on someone who has microgenia with a nasal dorsal hump will clinically make the nose more appealing and even appear smaller because of a more proportionate face overall. Patients requiring orthognathic surgery who have maxillary hypoplasia along with malar hypoplasia may have other problems that contribute to the aesthetics of the nose; therefore achieving the patient’s overall desire may require more than a simple rhinoplasty. Simultaneous orthognathic surgery and rhinoplasty can be performed, but one must understand that major tip changes may occur when the entire maxilla and its anterior nasal spine are moved (Figures 8-23 and 8-24). Also, the nasal base must be controlled with intraoral alar base cinch sutures, since releasing the periosteum at the pyriform rim allows the nasal base width to widen. Like any aesthetic surgery of the face, proportion is key in attaining a harmonious and natural appearance, keeping in mind that good function is absolutely critical.

Function of the nose can be assessed by several methods, including simply having the patient take deep breaths in while holding the nose closed on either side. Other tests involve cotton-tipped applicators placed just inside the nose or a caudal test with a finger pulling on the skin on the outside of the nose to assess internal valve problems. Noting valve problems beforehand, both internal and external, can help prevent an unhappy patient postoperatively. It is much easier to prevent these problems with spreader grafts performed during the primary surgery if indicated rather than performing reconstructive surgery on an operated nose that has significant scar tissue (see Figure 8-75).53

Patients who have already undergone previous nasal surgery may have external nasal valve collapse from overresection of the lower lateral cartilages. External nasal valve collapse can also be seen in a thin or narrow nose, a very aged nose, or even in patients with some facial paralysis.54–57 Internal nasal valve collapse that may have been created by scarring from previous rhinoplasty surgery often requires spreader grafts to correct. The Cottle test for diagnosis of nasal valve collapse is performed by using your finger to pull laterally on the cheek and lateral wall of the nose to open the nasal valve. Classically, patients breathe much easier when this test is performed (positive Cottle sign). Breathe Right strips, regularly used by athletes, have adhesive that allows the device to act as a temporary spreader graft. The splints open the internal nasal valve from the skin side and do allow at least temporary increase of nasal airflow whether nasal valve collapse exists or not. Actual inspection inside the nose with a nasal speculum can help identify any major perforations that could be caused by pathology or even a history of cocaine use. The speculum exam will also note any major deflections of the septum as well as enlargements or asymmetries of the turbinates. The state of the nasal mucosa, such as inflammation from allergies, should be noted during an intranasal exam.

Treatment Planning

A good treatment plan prior to rhinoplasty surgery is an absolute necessity. It is critical to plan for possible problems requiring additional procedures such as graft harvesting from behind the ear, rib, hip, or other location. Presurgical photographs along with possible radiographs, such as cephalometric radiographs, may be helpful in deciding on a sequence to the surgery and a detailed plan (see Figure 8-19). Many surgeons will also use waxed paper overlays to mark out exactly what they are hoping to achieve, which can be invaluable when beginning one’s rhinoplasty surgical career. A logical treatment order should be planned and followed. As an example, portions of the procedure that may increase bleeding (e.g., osteotomies) should not be performed early during the surgery, since they could create problems during delicate cartilage work. Most surgeons will develop their own comfortable treatment outline and follow the general treatment order each time.

External Versus Endonasal Technique

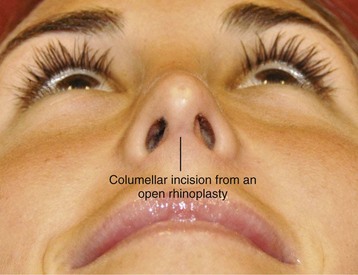

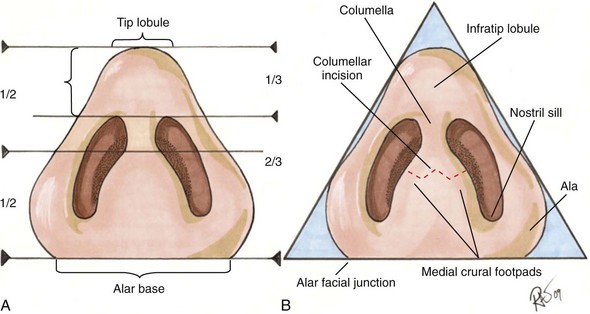

The argument for or against an open or closed rhinoplasty will likely exist for at least a few more decades and be easily argued either way. Certainly there is no one technique that maintains clear superiority over another. The advantages of an open or external rhinoplasty are obvious in that it has superior visualization; in most surgeons’ hands, the ability to place grafts or reduce cartilage can be performed more precisely. The argument for a closed technique involves the possibility of less disruption of blood supply and lymphatics, leading to possibly less postoperative edema. The other obvious advantage is that no external scar would be present. Also, some feel it may be faster in their own hands and is less disruptive to some of the attachments that may allow for better support of the nose. Although I personally use both techniques depending on the particular situation, the external open rhinoplasty is certainly an easier approach in my hands and allows for teaching purposes. The main benefit from using an open rhinoplasty is the ability for more precise placement of tissue grafts. Fortunately, the external transcolumellar scar, if placed well and meticulously closed, is rarely ever an aesthetic complaint. In the vast majority of cases, it is nearly invisible after prolonged healing (Figure 8-25). It is critical to understand nasal base proportions and where ideally to place the external incision just above the medial footpads to allow for optimum healing (Figure 8-26).

The debate over closed versus open rhinoplasty could go on indefinitely.58–61 As with any surgical procedure where multiple techniques exist, the best technique is actually the one that works best for you. The typical patient will simply be happy if their surgery goes smoothly and the results are all they had hoped to achieve, regardless of the incision type chosen.

Incision Options

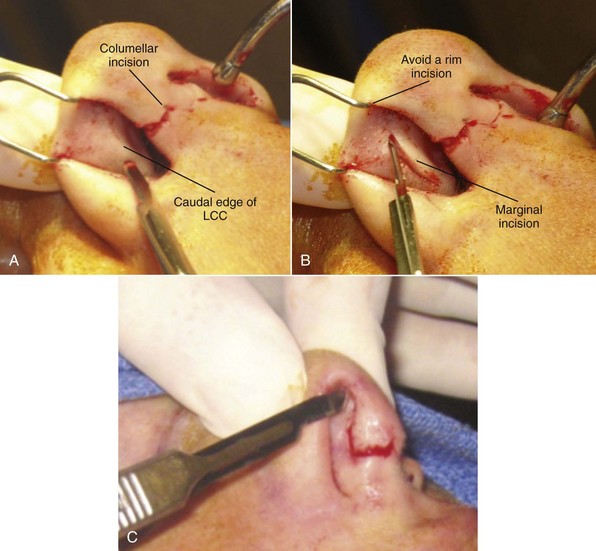

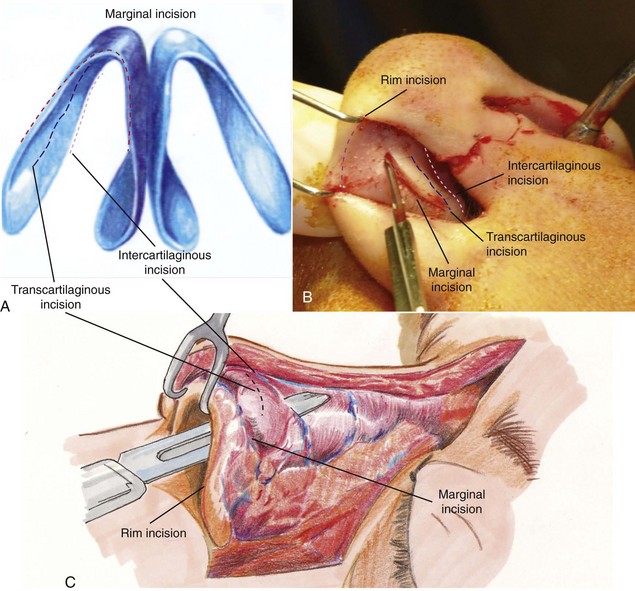

Multiple incision options exist for various rhinoplasty techniques; however, the external rhinoplasty has the most standard incision, which involves a transcolumellar incision that is blended into a marginal incision. The marginal incision is one that can be used for either an open or closed technique. A marginal incision is an intranasal incision that essentially hugs the caudal margin of the lower lateral cartilages while the caudal margin of the lateral crural cartilage typically follows just along the entire extent of the lower lateral crus (Figure 8-27). As the incision approaches the facet or internal crus, it often can be made 1 to 2 mm more cephalic than the actual margin of the cartilage to help prevent alar retraction. Also, the marginal incision along the medial crus can be made further cephalically than the actual margin if significant treatment of the medial crus or placement of a strut is indicated. This allows for more exposure of the medial crural cartilages than would be attained if the incision were truly at the marginal edge.

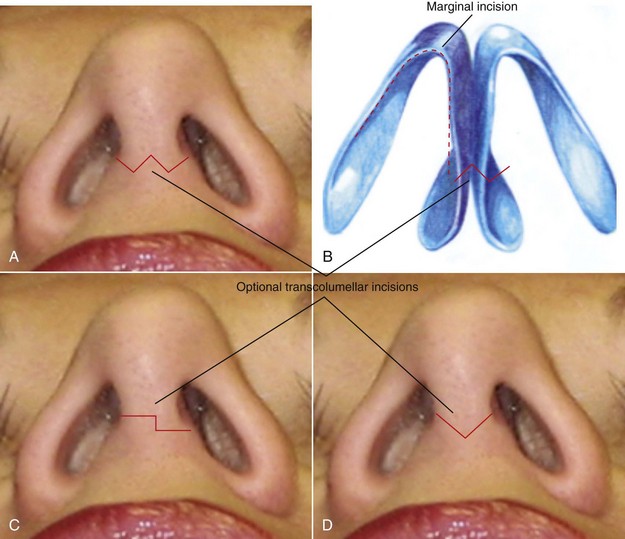

For the transcolumellar portion of the external rhinoplasty, the incision should be made with a #11-blade scalpel to create precise edges and distinct corners in which reapproximation can be made easily and predictably. The incision should also be placed in a location that would be at least visible postoperatively, typically about a third of the distance from the alar base, extending up toward the nasal tip. This usually corresponds with the top of the nasal footpads of the medial crural cartilages. The actual shape of the incision is variable. A straight-line incision should be avoided because this would leave the most noticeable scar and possibly some notching laterally. Various shapes and techniques have been used to perform this transcolumellar incision, the most common being either a stairstep technique or a W or inverted V incision (Figure 8-28). The key to having an incision that looks nearly invisible postoperatively is meticulous surgical technique where tissues are not crushed or compromised by inappropriate retraction. The tissue in the columellar area can be very thin, and rough manipulation can create poor healing postoperatively. Care must be taken in elevating this flap to prevent crushing the tissue or excessive stretching with retractors. Closure of the columellar incision must also be meticulous, using interrupted sutures in a precise fashion to ultimately achieve a very well-hidden scar during open rhinoplasty.

Incisions for a closed rhinoplasty can be more varied, depending on what needs to be accomplished and surgeon preference. The marginal incision is still the most basic and common incision for an internal or closed rhinoplasty. It typically stops at the base of the medial crural footpad rather than having an extension across the columella. The medial extent of the marginal incision can also extend inferiorly if additional access is required for septoplasty or for cartilage harvesting. Another optional incision for an endonasal approach is the transcartilaginous incision, which is performed approximately in the midportion of the lateral crus or lower lateral cartilages and can also be extended medially and inferiorly for septoplasty as required. The advantage of a transcartilaginous incision is limited dissection to remove a cephalic strip and avoid the scroll area between the upper lateral cartilages that may prevent problems with support. Through one transcartilaginous (or intracartilaginous) incision, a surgeon can both thin the nose by removing cephalic cartilage of the lateral crus and gain access to the dorsum for dorsal reduction. The transcartilaginous (intracartilaginous) incision, endorsed heavily by some surgeons, is somewhat more challenging for the novice surgeon and does have limitations on the amount of work that can be performed through it, particularly complex grafting (Figure 8-29).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses