9 Cervicofacial Rhytidectomy

Like so many other things in life, the basics of facelift surgery are relatively straightforward, but the key to success is in the details, and the details take years to appreciate. Any given detail of the procedure may work well for some surgeons but not so well for others. Facelifts can be taxing; they can take from  to 4 hours. Most frequently, I am doing concomitant procedures such as blepharoplasty, brow lift, laser resurfacing, chin and cheek implants, and so forth along with the facelift. This sometimes translates into 5- to 6-hour cases. This has required me to make many changes in my office. I had our facility accredited by the Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care (AAAHC) and equipped hospital-caliber operating rooms (Figure 9-1).

to 4 hours. Most frequently, I am doing concomitant procedures such as blepharoplasty, brow lift, laser resurfacing, chin and cheek implants, and so forth along with the facelift. This sometimes translates into 5- to 6-hour cases. This has required me to make many changes in my office. I had our facility accredited by the Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care (AAAHC) and equipped hospital-caliber operating rooms (Figure 9-1).

My original discipline is maxillofacial surgery, so I am well trained in ambulatory outpatient anesthesia and licensed in my state to perform intravenous (IV) sedation and general anesthesia. For many short procedures on healthy patients, we are able to use IV sedation with tumescent anesthesia. For longer cases or those on older or medically compromised patients, we use nurse anesthetists or physician anesthesiologists. I have also built a hospital-grade recovery suite suitable for ambulatory outpatient anesthesia but capable of overnight stay with nursing care (Figure 9-2). I have privileges at several local hospitals and surgery centers but rarely use them (with the exception of cases of medically compromised patients), opting for the convenience of my office surgery center. Although I believe I currently have a state-of-the-art facility, this did not happen overnight. Over the past 12 years, I have upgraded from relatively humble but safe facilities as the practice grew and the patient base expanded.

Facelift History

The scientific literature is replete with descriptions of early facelift techniques from the early 20th century that primarily detailed skin tightening and excision.1–11 In 1973, Skoog presented a technique of elevating the platysma muscle without detaching the skin.12 In 1976, Mitz and Peyronie described the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS),13 and later other authors described techniques of SMAS plication and imbrication.14–16 By the late 1970s and mid-1980s, a combination of complete platysmal muscle transection, plication of medial borders, and pulling laterally was presented as the way to get the “best result.”17,18 Patient complaints, complications, and overoperated necks occurred, and many of these techniques were abandoned.19 Deep-plane and subperiosteal techniques have been described by multiple authors,20–22 as well as endoscopic approaches.23

Many other techniques have been described, and some surgeons have gone as far as “inventing” new techniques and patenting catchy names to describe some minimally invasive facelift that is supposedly revolutionary. For the most part, these “new” techniques are a rehashing of previously described techniques (Figure 9-3). When reviewing the literature, it should be kept in mind that just because a technique has been published or promoted does not mean it is better or safer. It will be mentioned many times throughout this chapter that patient safety and outcome are testaments to “the best” facelift technique. Some techniques may work well in the hands of a given surgeon, and if they provide safe procedures with great outcomes, then they cannot be criticized. For the novice surgeon, however, it is preferable to begin with safe and predictable techniques before advancing to more complex procedures. Walk before you run!

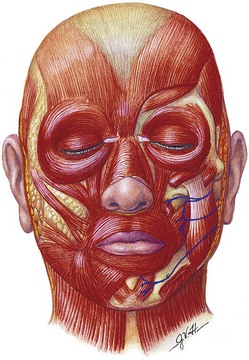

Facelift Anatomy

The next layer is the subcutaneous layer (Figure 9-4). This is the layer of fat that is intimate to the dermis superficially and also with the deeper SMAS. The subcutaneous layer is basically a safe layer in the face and can be undermined in the subcutaneous plane without damage to significant anatomic structures. This layer is of varying thickness depending upon the location and patient. This layer also becomes thickened over the malar region, where dissection can be tenuous. This tissue is attached to the malar periosteum by retaining ligaments that run from the underlying periosteum through the malar pad and insert into the dermis. This area is very tenacious and because of its fibrous nature provides resistance when dissecting; it is referred to as McGregor’s patch. Brisk bleeding is also frequently seen in the area due to accompanying vasculature.

The third layer is the SMAS layer. This layer separates the overlying subcutaneous fat from the underlying parotid-masseteric fascia and facial nerve branches (Figure 9-5). The SMAS layer, as described by many leading authors, is said to be continuous with the galea in the scalp, the temporoparietal fascia in the temples, and the superior cervical fascia in the neck. This structure was initially described by Mitz and Peyronie as muscular and fibrous tissues and termed the superficial musculoaponeurotic system.13 They stated the SMAS exists in the parotid and cheek region and invests the muscles of facial expression. In their original article, the authors state, “To us, the SMAS appears to be a fibromuscular network located between the facial muscles and the dermis, one which covers the facial motor nerves.” They note that the SMAS separates two layers of fat in the face into superficial and deep layers. Their work also implied that the SMAS was continuous with the platysma.

Various authors contest Mitz and Peyronie’s finite description of the SMAS and related layers, and some surgeons do not agree that there is any such thing at all as the SMAS. Jost and Levet24 refuted the work of Mitz and Peyronie and dispute their findings. In this study, the authors combine embryology and comparative anatomy of other mammals as well as cadaver dissections and summarize that the SMAS as described previously is incorrect. These authors describe the SMAS as a double-layered system. The first layer is the superficial system which is consistent with primitive platysma and includes parotid fascia and has no direct bone insertion. In addition, they state that a deep system exists which includes the sphincter coli profundus. This group of muscles in the perioral region does possess bony attachments. These authors also contradict Mitz and Peyronie and state that the SMAS is not continuous with the platysma, but rather it is the parotid fascia that is continuous with the platysma. Additionally, they comment that the parotid fascia is the uppermost part of the primitive platysma, which is a muscle that has undergone fibrous degeneration. Applying this to facelift surgery, these authors suggest dissection deep to the parotid fascia.

In an additional article denying that the SMAS exists as originally described,25 Gardetto et al. state that according to the work of Mitz and Peyronie, “no SMAS exists in any of the described regions that agrees with the basic criteria of Mitz and Peyronie.” This paper corroborates through comparative anatomy and fresh cadaver dissection studies that the “SMAS does exist in the parotid region, where it is thick but becomes very thin and discontinuous in the cheek where it is impossible to identify or dissect it, even with microsurgical technique.” They further state that “there is no evidence of continuity of the SMAS and the temporal fascia but in contrast, in the lower eyelid there is continuity with the lateral portion or the orbicularis oculi muscle.”

Having said all this, one can call the fibromuscular layer anything they wish (or deny its existence). Most surgeons will agree it separates the subcutaneous fat from the underlying parotidomasseteric fascia. When a surgeon states that they pick up the SMAS, in reality they are picking up adipose tissue of the subcutaneous fat and fibromuscular tissue above the parotidomasseteric fascia. This is what is frequently plicated, excised, imbricated, and otherwise managed in facelift surgery (Figure 9-6). Whether you agree about the embryology and histology, we will refer to this layer as SMAS throughout this text. All motor nerves providing movement of the facial muscles are deep to this plane. When this layer is stretched or pulled, it pulls on the mimetic muscles and basically moves the entire lateral face in the desired vector. This makes sense; it is said that the physiologic function of the SMAS is to more effectively transfer mimetic muscle movement to the facial skin by septae that extend from the SMAS to the dermis. In theory, this would allow the face to move more as a unit (as opposed to each individual muscle), thus making expression more efficient.

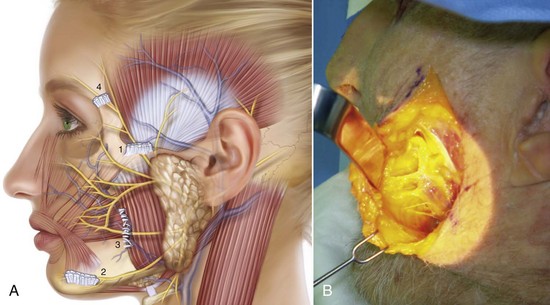

The fourth surgical plane commonly involved in facelift surgery is the sub-SMAS plane (Figure 9-7). This surgical plane contains the facial nerve motor branches and the parotid duct and is best avoided by novice surgeons. The facial nerve branches are deeper in the parotid gland until they emerge at the anterior border of the gland and cross the masseter muscle. The parotidomasseteric fascia is the facial layer that overlies the parotid gland and masseter muscle; when operating superior to this layer, the facial nerve branches are generally protected. Just as the SMAS is an extension of the superficial cervical fascia, the parotidomasseteric fascia is an extension of the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia into the face and the deep temporal fascia above the zygomatic arch. The novice surgeon should not violate the parotidomasseteric fascia, although many seasoned surgeons perform deep plane dissections beneath the layer routinely. Obviously the deeper and more anteriorly the dissection proceeds beneath this layer, the greater the chance of injury to the facial nerve branches. There is a sub-SMAS loose areolar tissue plane that extends from the anterior border of the parotid to the anterior border of the masseter. Blunt dissection in this plane allows the deep plane facelift dissection to proceed safely even though it is almost intimate with the underlying facial nerve branches.

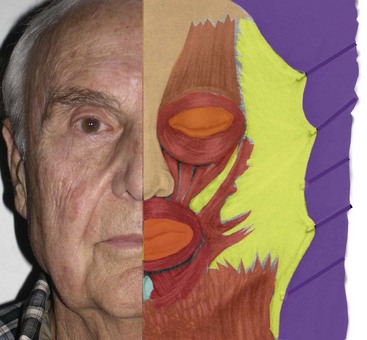

One reason the facial nerves are protected in deep plane dissection as they branch in the anterior face is that most nerves innervate the muscle on its posterior surface. The only muscles of facial expression that are exceptions are the levator anguli oris, the buccinator, and the mentalis, which are all innervated on their anterior surface (Figure 9-8).

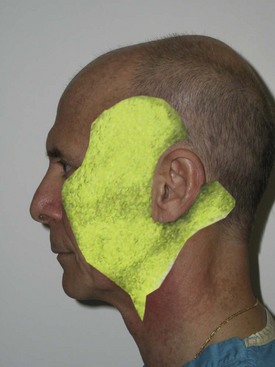

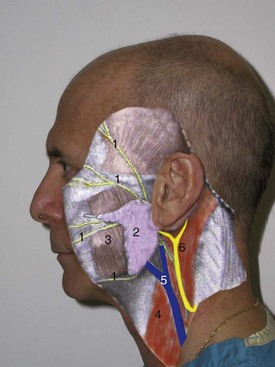

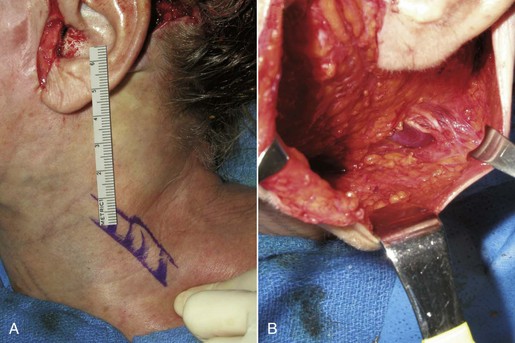

Several other structures are frequently encountered in facelift surgery and are vulnerable to injury. The sternocleidomastoid muscle is significant because the external jugular vein and greater auricular nerve are intimate and traverse this muscle in the midlateral neck (Figure 9-9). The greater auricular provides sensory innervation to the earlobe and lateral cheek. The external jugular vein and greater auricular nerve lie deep to the SMAS and are protected as long as the dissection remains in the subcutaneous plane. The subcutaneous tissue becomes very thin in this part of the neck, and the dermis is sometimes intimate to the fascia of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, which can put the nerve and vein in jeopardy.

The youthful face is in part suspended by retaining ligaments that support the skin over the facial bones. These ligaments become lax with age and in part are responsible for the sagging of facial tissues. This connective tissue can run from bone to dermis (osteocutaneous ligaments) or from soft tissue to dermis (cutaneous ligaments). The exact name and location of these ligaments are described differently by various authors but collectively can be appreciated during facelift dissection, where they can be felt (fibrous tissue difficult to bluntly dissect) or visualized directly. Figure 9-10 shows a rendition of the approximate position of these retaining ligaments.

Patient Selection

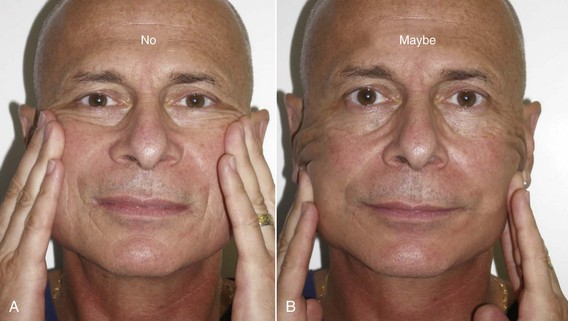

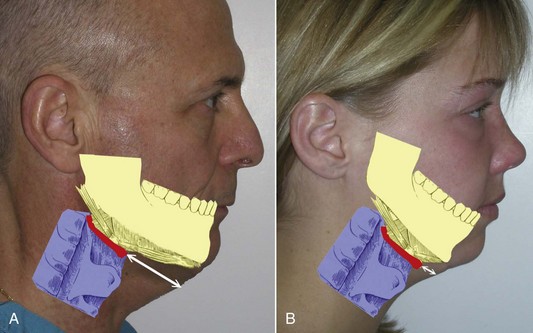

Many patients are surprised when I explain that a facelift is a procedure primarily for the lower face. It is not uncommon for patients to present and request “just a little tuck to pull back my cheeks.” They place their fingers on their cheeks and reset their cheeks, jowls, and neck (Figure 9-11, A). It must be explained to these patients that no procedure exists that corrects aging in that vector. By pulling the skin in a more lateral direction, a more representative correction can be explained (see Figure 9-11, B). A more accurate means of illustrating the potential changes from cervicofacial rhytidectomy is to place the patient supine and have them look in a mirror while elevating their chin. By removing gravity from the equation, the brows and midface are elevated, and the jowls and neck are vastly improved. I find this to be a relatively accurate prediction of the final lower face result (Figure 9-12). Obviously, digital morphing can be performed, but oftentimes the patient will set their sights on the morphed postop image and express unhappiness if that picture is not duplicated by the surgery.

FIGURE 9-12 Placing the patient in a recumbent position negates gravity and provides an idea of the facelift result.

Many classifications exist for grading aging changes, but I truly believe it is easier to think in terms of small, medium, and large (Figure 9-13). As stated earlier, a facelift is primarily a procedure for the lower face. No other procedure can address the jowls and sagging neck. Many shortcuts exist, such as liposuction and submentoplasty, but in the average patient with noticeable aging changes, cervicofacial rhytidectomy is a time-proven procedure to provide natural and lasting results.

Patients with large neck and jowl changes are poor candidates for the novice surgeon. Beginners should initially concentrate on thinner patients with mild aging and normal chin position. When considering candidates for rhytidectomy, chin and submental position is also of significant consideration. In patients with retrognathia or microgenia, the final result will not be as dramatic unless chin augmentation with implants or osteotomy is performed. Even more important is the position of the hyoid bone and associated muscles of the submental region. In patients with a hyoid position and laryngeal anatomy that is superior and posterior, the skin can be pulled to form an acute angle that approximates 90 degrees (Figure 9-14, A). Patients with this type of anatomy are better candidates than those with inferior and posteriorly situated hyoid bones and submental anatomy (see Figure 9-14, B). The novice surgeon must realize these implications. On patients with anatomy consistent with Figure 9-14, B, chin augmentation can improve the final outcome, but these patients must realize that their particular anatomy limits the result when compared to a patient with normal hyoid and submental position. I keep a picture of Figure 9-14 in my evaluation rooms to explain this concept to prospective patients.

Correct diagnosis of the patient’s condition and how best to improve it can be a challenge for the novice surgeon. Appreciating the vectors of facial aging (described in Chapter 1) can shed light on an orderly manner for the diagnosis and rejuvenation of the aging face. Figure 9-15 shows a rendition of a patient with panfacial aging and the respective vectors that need correction. Having a mental picture of this can assist the surgeon in developing an appropriate treatment plan. Actually showing a picture similar to Figure 9-15 to the patient can improve their understanding of the proposed surgery.

Determining Status for Potential Cosmetic Facial Surgery

Psychological Stability

Over the past 25 years, I have seen repeating red flags for cosmetic surgery:

Facility

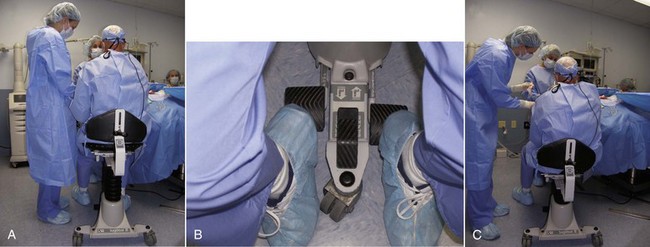

There is no substitute for a formal operating table, and these can be purchased refurbished. Alternatively, a dental or minor surgical chair can suffice. Having the ability to position patients laterally (airplane) can be of great assistance, especially with older patients with limited neck mobility which makes positioning the head difficult. This prevents the surgeon from bending over and working in a hole. An additional item that has become personally indispensable is an operator stool that can be vertically repositioned (Figure 9-16). Cosmetic facial surgery and especially facelift surgery requires many different patient and surgeon positions, and having the ability to pump up or lower the stool makes it much easier to perform seated surgery. I begin in an elevated position but frequently “drop down” to look under the preauricular flaps and other structures.

Instrumentation

Although many specialized instruments exist specifically for rhytidectomy, in reality the procedure can be performed with relatively basic surgical instruments most surgeons already have in their offices (Figure 9-17). A basic list follows:

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses