Gingival Recessions

Giano Ricci

Introduction

A frequent occurrence in periodontal and nonperiodontal cases is the presence of localized gingival recession, which may jeopardize the patient’s esthetics.

Definition

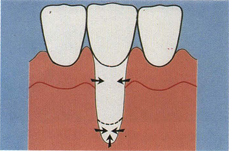

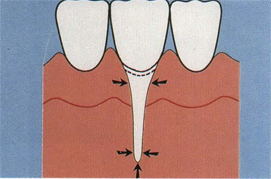

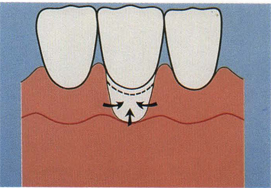

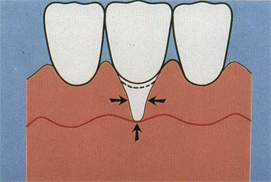

A gingival recession may be defined as the exposition of the radicular surface of the tooth due to the destruction of the marginal gingiva and of the epithelial attachment that will be reestablished at a more apical position. The recession may appear as a cleft of the gingival margin or may consist of the partial or complete loss of the gingiva on the radicular aspect of the tooth (Figs 8-1 and 8-2). A fenestration can be defined as the situation in which the buccal plate of bone is partially missing and part of the root is exposed but the marginal bone is intact (Fig 8-3). When the marginal bone is also missing, a dehiscence is present (Fig 8-4). In this case the root is just covered with soft tissue; therefore, it can be easy to have a recession in that area if plaque alone or plaque associated with trauma is present in the area.

Symptomatology

The symptomatology of the gingival recession may consist of dentinal hypersensitivity, marginal inflammation, root decay, pulpal pathology, and psychologic and esthetic problems, especially if the recession is present in the anterior region in a patient with a high smile line.

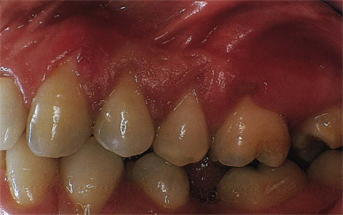

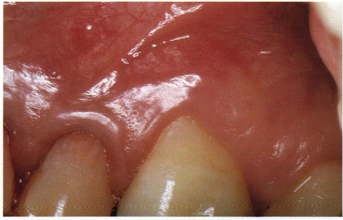

Fig 8-1 Deep and narrow localized gingival recession (clefts).

Fig 8-2 Large and shallow localized gingival recession in a case of advanced periodontitis.

Fig 8-3 Fenestration.

Fig 8-4 Dehiscences and fenestrations in a skull

Etiology

The etiology of gingival recessions consists of determinant factors and cofactors (Table 8-1).

| Table 8-1 Etiology of gingival recessions | ||

| Determinant factors | Cofactors | |

| Bacterial plaque | Tooth malposition | |

| Trauma from toothbrushing | Unfavorable anatomy | |

| Iatrogenic factors | Occlusal trauma | |

| Habits | Ortho movements | |

The most important of determinant factors is the bacterial plaque. O’Leary et al1 found a direct correlation between the increase of plaque index and the increase of gingival recessions. Trauma from toothbrushing is another factor and it is frequently associated with erosion of the root’s surface. This is the major etiologic factor in the establishment of gingival recessions in young patients who, in an effort to perform good oral hygiene, damage the gingival tissue by using an improper technique or a wrong toothbrush. The horizontal use of the toothbrush is one of the major causes of recessions on canines and premolars.2 These lesions are frequently observed on the opposite side of the hand that the patient normally uses (left side for a right-handed person). Also, iatrogenic factors, such as amalgam or prosthetic overhangs, clasps, and orthodontic appliances that impinge on the soft tissue, can determine gingival recessions for mechanical aggression or because they facilitate the accumulation of plaque.

Procedures for impression taking, such as the improper use of a retraction cord and electrosurgery on a thin gingival tissue, can cause gingival recessions. The trauma induced by habits, such as toying with the soft tissues with fingernails or foreign objects, is also a cause. Tooth malposition, such as buccally displaced teeth or rotated teeth because of the altered tooth–bone relationship, may act as a cofactor in the onset of gingival recessions, as well as anatomic situations, such as high frenum insertions and a shallow buccal fold that will produce tension on the marginal gingiva. In the past gingival recessions have also been associated with trauma from occlusion,3 but more recently this concept has been refuted.4

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of the recessions in most instances can be related to the presence of a localized inflammation that destroys the epithelium and the connective tissue. The epithelium tends to migrate through the connective tissue and, when the two epithelium layers meet, the recession occurs (Figs 8-5a to c). In the case of recession from brushing or from other habits, this recession takes place because of the trauma itself and no inflammation is present.

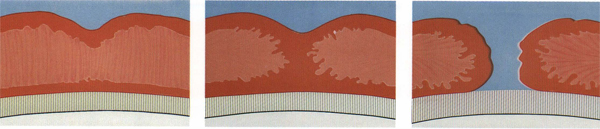

Figs 8-5a to c Schematic representation of the pathogenesis of a gingival recession. The sulcular epithelium proliferates through the connective tissue and joins the oral epithelium. The epithelium undergoes necrosis and a recession is formed.

Historical rationale and treatment techniques

The predictability of the root coverage is much higher with the use of pedicles than with free grafts, especially in the presence of wide and deep defects according to the classification made by Sullivan and Atkins5 (Figs 8-6a to d).

Fig 8-6a Wide and deep recession.

Fig 8-6b Narrow and deep recession.

Fig 8-6c Wide and shallow recession.

Fig 8-6d Narrow and shallow recession.

Figs 8-6a to d Classification of gingival recessions according to Sullivan and Atkins. Arrows indicate the source of vascular proliferation for the establishment of vascular bridging to ensure taking of a graft.

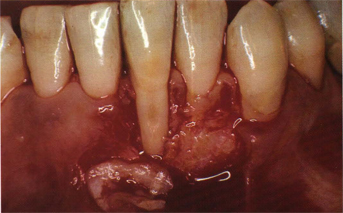

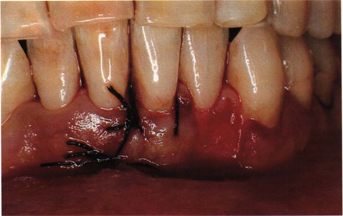

Figs 8-7a to d Split-thickness laterally positioned flap.

Fig 8-7a Case of advanced periodontitis before treatment.

Fig 8-7b Recipient site preparation. Note donor site covered by periosteum.

Fig 8-7c Split-thickness flap sutured on the area of gingival recession.

Fig 8-7d Healing after 2 years.

More recently new techniques have been developed to take advantage of both procedures using a free connective tissue autograft, over which a pedicle is placed,6,7 or by placing a connective tissue autograft in a mucosal pouch to provide better nourishment to the graft.8 Root coverage may also be enhanced through a creeping attachment, a phenomenon by which the gingiva tends to migrate coronally through the years as long as the roots are plaque-free. After a year the average migration of attachment can be 0.46 to 0.89 mm.9 This phenomenon is frequent with the use of free grafts but can also be noticed with pedicle grafts. Occasionally, a recession on the donor site of the pedicle can be noticed. For this reason Guinard and Caffesse10 have proposed the use of a free graft to protect the donor site with good results. The same results can be obtained by using dura mater.11

To enhance the healing potential of a pedicle over the root, Goldman and Smukler12 proposed the transfer of a full-thickness flap with stimulated periosteum. The procedure consists of irritating and therefore stimulating the cellular proliferation at the donor site with a needle 20 days before transferring a full-thickness pedicle graft over the denuded root. The results of this technique have yet to be proven.

The type of therapy of gingival recessions depends on the quality and quantity of gingiva that is present near the area of recession. If there is an adequate zone of attached gingiva that can be used, it is possible to perform a surgical procedure that will consist of the following:

1. Laterally positioned flap (partial-thickness, full-thickness, and mixed-thickness).

2. Double papilla flap.

3. Coronally positioned flap.

When an adequate zone of attached gingiva is not present in the surrounding area, it is then possible to use the following:

1. Free gingival graft.

2. Free gingival graft and coronally positioned flap.

3. Free connective tissue graft (envelope technique).

4. Free connective tissue graft and pedicle (subpedicle connective tissue graft).

Laterally positioned flap

The first surgical approach to the therapy of isolated gingival recession has been proposed by Groupe and Warren.13 The technique (Figs 8-7a to d) consists of the following steps:

1. Preparation of the exposed root with scaling, root planing, use of chemicals, and flattening of the root curvature.

2. Incision and removal of a thin band of marginal gingiva around the recession, exposure, and preparation of a firm periosteal bed to allow perfect adaptation between the pedicle and the recipient site.

3. Exposure and stimulation of periodontal ligament.

4. Full-thickness flap including the marginal gingiva with vertical incisions oriented toward the base of the defect raised from the donor site. The base of the pedicle must correspond to the recipient site. If tension is present on the pedicle, a horizontal incision can be added to the vertical incisions (cut back).

5. Full-thickness flap is sutured in the most coronal position on the recipient site.

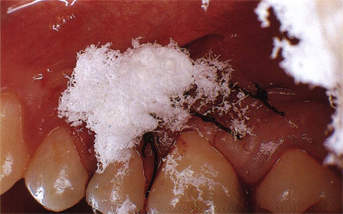

6. Protection of the donor site with a split-thickness flap, a free gingival graft, dura mater, or microfibrillar collagen (Figs 8-8a to f).

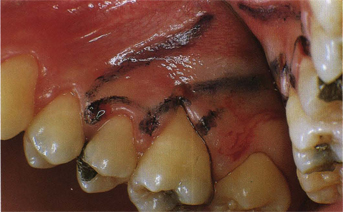

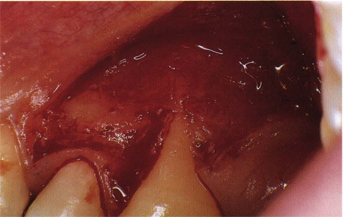

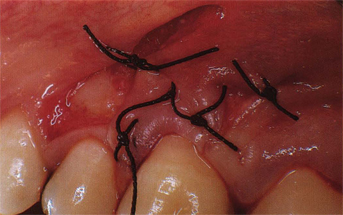

Figs 8-8a to f Full-thickness laterally positioned flap. Protection of donor site with microfibrillar collagen.

Fig 8-8a Initial lesion.

Fig 8-8b Outline of flap design.

Fig 8-8c Recipient site prepared (note exposed bone on donor site).

Fig 8-8d Flap sutured.

Fig 8-8e Donor site protected with microfibrillar collagen.

Fig 8-8f Healing after 5 years.

Figs 8-9a to f Split-thickness laterally positioned flap and root preparation with citric acid.

Fig 8-9a Initial lesion after curettage.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses