8

Cosmetic Dentistry: Concerns with Facial Appearance and Body Dysmorphic Disorder

- The more dissatisfied people are with their teeth, the greater their desire for treatment to correct a perceived imperfection.

- The desire to make changes to appearance could be a symptom of a lack of self-worth, negative self-image, or a psychiatric condition called body dysmorphic disorder (BDD).

- It is important to remain vigilant and practice restraint with patients with unusual esthetic requests.

- There is no support for the notion that cosmetic dental treatment leads to long-term improvements of happiness or quality of life.

Appearance is considered important by many as it is assumed to provide the opportunity for obtaining attention, love, recognition, and validation from the environment. Indeed, attractiveness appears to be associated with achieving happiness in life. Research has shown that the more attractive a person is, the more likely it is that he or she will achieve greater professional status, a higher income, and more happiness (Umberson & Hughes, 1987). The additional attention attractive children receive from people, not only from parents but also—for instance—from teachers at school, may create opportunities for them to flourish, thereby stimulating self-confidence and intelligence. This results in physically attractive people being seen as smarter and more competent later in life (Beehr & Gilmore, 1982; Shahani, Dipboye, & Gehrlein, 1993). Hence, if a person meets the criteria for attractive appearance, the odds are that his or her life will be good. Conversely, of individuals who feel they do not fulfill the norm for beauty, life can be unbearably painful, empty, or lonely.

In fact, very few people are 100% satisfied with their appearance. The results of a survey among a representative sample of the Dutch population for which people were asked about how they felt about their own body showed that about half of respondents felt they were unattractive, ugly, disfigured, or not beautiful enough (De Jongh et al., 2006; Gresnigt-Bekker et al., 2008). It appeared that 38% of men and 61% of women were dissatisfied with their appearance. Participants were also asked to indicate which parts of their bodies they were unsatisfied with (see Table 8.1). The majority found their belly to be the least attractive body feature. Men placed their teeth fifth on the list of most unattractive features. People’s dissatisfaction with their appearance in a general sense was also found to be positively associated with dissatisfaction about their teeth (Gresnigt-Bekker et al., 2008).

Table 8.1 Body Parts about Which People Are Most Dissatisfied (De Jongh et al., 2006)

| Ranking | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Belly | Belly |

| 2 | Head hair | Breasts |

| 3 | Facial skin | Legs |

| 4 | Feet | Bottom |

| 5 | Teeth/nose | Thighs |

Given these findings, it is conceivable that the more dissatisfied people are with their teeth, the greater the desire for treatment to correct this perceived imperfection (Klages, Bruckner, & Zentner, 2004).

This chapter focuses on the dissatisfaction people have with their appearance and their striving to improve it. Although many people expect improving their teeth will make them happier, this notion may be less logical than it seems. This holds true specifically for people with an actual obsession regarding their teeth, a psychiatric syndrome called body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), which can be a real scourge for dentists, orthodontists, and oral surgeons. This chapter addresses a number of dangers and common pitfalls regarding the dental treatment of patients with excessive desires, particularly those suffering from BDD, and provides some guidelines and tips for dealing with these patients.

Cosmetic Interventions Increasingly Popular

Cosmetic or esthetic interventions have grown in popularity in recent years. In 2009 alone, over 1.6 million Americans underwent such treatments, an increase of 155% compared with 1997 (American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, 2011). This increase includes both surgical treatments, such as breast augmentation and eyelid surgery, and nonsurgical treatments. The latter includes botox (botulinum toxin Type A) injections and laser hair removal. The greatest increase took place in the latter area, with a rise of 228% in the same period.

One reason often given for this increase in cosmetic interventions is media exposure. Reality TV programs such as the popular “Extreme Makeover,” which have showcased all manner of new developments in cosmetic medicine over the past few years, are extremely popular. The assumption that these kinds of television programs play an important role in prompting people to undergo cosmetic interventions is supported by the results of a study among patients undergoing cosmetic surgery for the first time. Four out of five patients indicated that “beauty” programs on television influenced them in their decision to undergo such cosmetic surgery (Crockett, Pruzinsky, & Persing, 2007).

The same developments can be seen occurring in the field of dental cosmetic interventions. Dentists in New Zealand received numerous requests for cosmetic dental treatments after the TV program “Extreme Makeover” was broadcast (Theobald et al., 2006).

A full 85% of patients linked the desired dental treatment to this program. It appears that existing dissatisfaction with one’s dental appearance is increased or strengthened by media attention and other forms of external information. It does not require a great deal of imagination to understand that this can affect feelings of self-worth. If self-worth is lacking, the likelihood of discovering physical imperfections increases, thereby further strengthening individuals’ negative self-image. It is conceivable that many people consider hiding or changing their perceived physical imperfection by means of plastic surgery because they assume that this will increase their happiness and quality of life (QoL).

Do Cosmetic Dental Interventions Have a Positive Effect on Patient Happiness and Quality of Life? A Study

Intriguingly, despite the large number of dentists’ web sites that essentially promise improvement in personal happiness and quality of life (QoL) following cosmetic dental work, until recently, research in the field of cosmetic dentistry was entirely lacking. One exception is a study that investigated whether personal happiness and QoL would indeed increase following cosmetic treatment (De Jongh et al., 2011). The experimental group consisted of 52 patients, with an average age of 46 years, who were about to undergo cosmetic treatment of their front teeth in one of the five cosmetic dental clinics that participated in the study. Treatments consisted of bleaching dental elements, application of veneers and crowns, or combinations of these interventions. Using a pretest–posttest with control group design, the effects of cosmetic treatment of the front teeth were compared with those within a group of 51 patients with an average age of 53 years who underwent restorative, not primarily cosmetic, treatments in the (pre)-molar area during the same period. In addition to general questions (e.g., gender, age, education, relationship status, and ethnicity of the participant), questions were asked about satisfaction with dentition, importance of dentition, and happiness. Additionally, questionnaires were used to assess oral health-related QoL (as indexed by the Dental Impact Profile; Strauss & Hunt, 1993; Strauss, 1997) and general QoL (using the 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey, SF-12; Ware, Kosinski, & Keller, 1996). Assessments were carried out prior to treatment, 3 days after treatment, and 1 month after treatment. Intriguingly, no significant differences were found between the experimental and control groups in terms of satisfaction with dentition, importance of dentition, happiness, and general QoL prior to treatment and 1 month later. Furthermore, no differences were found in results for these variables between both groups. The most noteworthy result was that in the experimental group, rather than an increase, a significant decrease in oral health-related QoL following cosmetic treatment was found. These findings certainly do not support the assumption that cosmetic treatment of front teeth yields meaningful positive changes in satisfaction about dentition, happiness, oral health-related QoL, or general QoL. In fact, the contrary is true for oral health-related QoL. Apparently, cosmetic dental treatment cannot simply be “translated” to improvement in QoL or happiness.

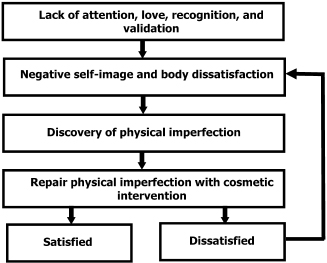

A possible explanation for negative effects of cosmetic interventions on patient happiness and QoL is that patients’ expectations prior to such interventions are high, so that if the results are disappointing, this may result in a drop in oral health-related QoL. This explanation for a lack of positive treatment result is consistent with the findings of a study among patients who had dental elements whitened, which found that 36% were dissatisfied with the final result (McGrath et al., 2005). There is always a chance that the patients will eventually realize that their appearance is still imperfect, once again leading to painful feelings of dissatisfaction, resulting in a search for new ways to feel better or fulfill certain desires. This can easily lead to people getting stuck in a vicious cycle of dissatisfaction and the desire to fix their physical imperfections, creating a kind of addiction to cosmetic interventions rather than the desired happiness (see Fig. 8.1).

Fig. 8.1. How “addiction” to cosmetic interventions may be maintained.

Another possible explanation for the decrease—rather than increase—in QoL following a cosmetic dental intervention, is that a visible change to dentition may be of relatively little value to an individual’s well-being. Individual circumstances and stressful life events, such as divorce or loss of a loved one, doubtless have a greater impact on a person’s well-being than a dental intervention. Conversely, there are indications that the quality of loving relationships and meaningful daily activities contributes more strongly to happiness than an attractive appearance (Diener & Seligman, 2002). Although this is hardly the most positive of messages for cosmetic dentistry, it is in agreement with other research. For example, a study among extremely anxious patients showed that QoL did not automatically improve even following thorough restoration of fully deteriorated teeth (Vermaire, De Jongh, & Aartman, 2008). Furthermore, research among the Dutch population found that the combination of satisfaction with one’s body and one’s teeth could not even explain 10% of the variation present in satisfaction (Gresnigt-Bekker et al., 2008). These results leave little room for optimism about whether an intervention to improve dental appearance is capable of inducing positive, long-term changes in happiness and QoL.

Body Dysmorphic Disorder

Few people have such a desire to improve their own appearance that they are disgusted or extremely ashamed of what they look like. Yet, this does occur. Some people find themselves so repellant that they dare not leave the house, while the physical abnormality is so minor that concern about it is clearly excessive. Such individuals are likely to suffer from a psychiatric condition called body dysmorphic disorder, or BDD (Sarwer et al., 1998), which is estimated to have a prevalence of 2% in the Western population (Rief et al., 2006). In order to meet the criteria for this psychiatric condition, the person must be preoccupied with a certain aspect of his or her appearance, suffer significantly because of this, while the consulted doctor or an unbiased observer can see nothing noteworthy. Box 8.1 lists a number of questions that patients may be asked to determine whether the patient meets the diagnostic (DSM-IV-R) criteria for BDD (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

- significantly interfered with your social life, school work, job, other activities, or other aspects of your life?

- caused you a lot of distress?

- affected your family or friends?

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses