24

Work Stress, Burnout Risk, and Engagement in Dental Practice

- Demands from the dental environment, when not adequately coped with, may result in professional burnout.

- Stimulating aspects from working as a dentist relate strongly to positive engagement and have a buffering effect on burnout risk.

- A strong relation exists between burnout risk and physical complaints.

- How dental students cope with study stress may be indicative for how they cope with professional demands later in their career.

- Since experiencing stress is highly determined by the interaction between the person and the environment, individually tailored prevention measures are an adequate means to prevent burnout.

Introduction

Does work cause illness? In most publications on work and health, the emphasis is on health risks as caused by work and work circumstances. The literature on work-related illness is abundant and describes nearly every imaginable kind of physical, psychological, or social malfunctioning as explained by work-related factors. So, it is plausible to state that work does cause illness indeed.

On the other hand, awareness grows that work also provides for a positive influence on a person’s life (Schaufeli, Bakker, & Salanova, 2006; Bakker et al., 2008). There is a growing stream of literature in which the health effects of “structured, goal-directed activities, of a compulsory kind” (also known as work) are described. Occupational therapy, for instance, is a widely used means for recovery. Even more so, from studies on unemployment, we know that loss of work may lead to serious health problems, including suicide risk. Therefore, the proper conclusion is that work contains both health-threatening as well as health-provoking aspects.

In this chapter, both the health-threatening and the health-provoking aspects of working as a dentist will be described, focusing on mental health. In particular, the interplay between work stress and burnout, and work resources and positive engagement, will be discussed, using the Job Demands–Resources Model as a frame (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). Finally, some remarks on dental student stress and pieces of advice for burnout prevention will be given.

Stress and Work

In its original meaning, stress refers to a condition in physics where pressure is put upon tissue, to the extent that the structure of the tissue is about to be irreversibly changed.

In psychology, stress refers to the variables that influence one’s well-being. This is usually meant in a negative way, distress would be the correct word, whereas it is also recognized that a certain amount of stress—eustress—is needed in order to be stimulated and achieve results. Work stress usually refers to the demanding aspects of work that cause a person to feel to be “under stress.” This illustrates the somewhat confusing way the word stress is used in everyday language; it is both used as a causal factor and as a result of things.

A common approach to work stress emphasizes the interaction between an individual and the work environment (Lazarus, 1995). When an individual evaluates the (work) situation as being threatening and does not know how to deal with the threat, then stress is likely to occur. The demands of the job, such as work contents, circumstances, terms of employment, and professional relations, in combination with one’s individual perception of predictability, controllability, and social support, can make identical work a nuisance for one person, while a joy for someone else (Gorter et al., 1998). Thus, one may perceive one’s work and the work environment to be demanding, and yet feel perfectly able to deal with the circumstances (coping).

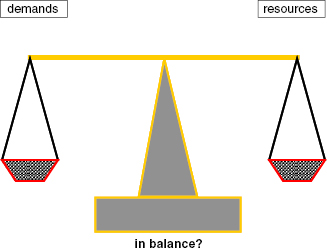

Work pressure is not only to be found in an overload of work, it can also be the result of a lack of fit between one’s personal capacities or ambitions. Things become difficult when one no longer feels capable of managing them, for instance, as a result of lack of energy. In other words, there is an interaction between the demands one is confronted with and the available resources one has. The perception of this interaction is highly subjective; one’s personal interpretation of demands and resources is decisive for one’s well-being. Demands and resources may be in or out of balance (Fig. 24.1).

Fig. 24.1. Balance between demands and resources.

As stated earlier, one performs best with a certain amount of tension or stress. Too little challenge can also be experienced as stressful. Having to deal with a chronic overload or a chronic lack of challenge may result in health complaints; physical complaints, negative thoughts, mood problems, changes in social relations, or changing behavior are symptoms that often coincide with being under chronic stress.

The Job Demands–Resources Model

A promising model to describe the interplay between demands and resources in the work setting is the Job Demands–Resources model (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004; Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). At the starting point of the Job Demands–Resources model is the assumption that regardless of the type of job, psychosocial work characteristics can be categorized into two groups: job resources and job demands. Job demands refer to those aspects of a job that require sustained physical and/or psychological effort and are therefore associated with certain physiological and/or psychological costs. Job resources refer to the physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of a job that (a) may reduce the negative effects of job demands, (b) are functional in achieving work goals, and (c) stimulate personal growth, learning, and development (Hakanen, Schaufeli, & Ahola, 2008).

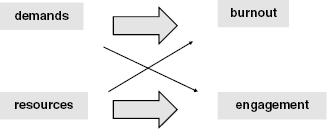

The interplay between job demands and resources may result in either health impairment, or motivation, to a certain extent (Fig. 24.2). Prolonged experience of job demands, without sufficient buffering work resources, may result in professional burnout, which is to be described later. Alternatively, when job demands are dealt with adequately, and work resources are plenty, positive engagement may be the result. Engagement will also be further described later. It is also understood that demands and resources have crossover effects on engagement and burnout.

Fig. 24.2. The Job Demands–Resources model (adapted from Bakker & Demerouti, 2007).

Burnout

A possible reaction to chronic work stress is burnout (Maslach, Jackson, & Leiter, 1996). Burnout is defined as

Burnout should be considered as a process; it is not so much a state of being burned out or not. Metaphorically speaking, burnout is like trail leading downhill of which one realizes he or she is upon it when already quite a distance going down. In another metaphor, one could speak of a battery still providing energy for light, but not receiving any input, and therefore running empty. In essence, burnout occurs to those dedicated to their job, willing to give much, and often not realizing or ignoring the fact that “the candle burns at both ends.” The dedicated professional realizes that all energy is used when this already is a fact. One is used to a pattern of demanding so much of oneself that the thought of postponing things or restricting oneself otherwise never occurs, or is ignored.

Positive Engagement

In recent years, research is also focusing on what is called positive psychology of work, in addition to a long history of studying health-threatening aspects of work. Work engagement is described as a multidimensional construct, defined as a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is defined by vigor, dedication, and absorption (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004):

Although conceptually apparently the opposite of burnout—also consisting of three underlying dimensions—recent research indicates that engagement is not to be seen that way (González-Romá et al., 2006). Burnout and engagement can be present in a professional at the same time to a certain degree.

How Do These Processes Appear among Dentists?

To illustrate the process of a dedicated professional in dentistry turning into a burnout victim, the dentist’s story in Box 24.1 is illustrative.

I graduated when I was 24, so now I have been a dentist for 15 years. As a student, I was already used to working quick and efficiently. When I graduated, the banks were all too keen to loan me money so I could start a brand new practice.

From the moment I started in my practice, I had one focus: all attention is for the patient. I did not pay much attention to creating a nice atmosphere for my staff, since I thought that everything that was not focused upon the patients’ needs was of secondary importance.

When patients had to wait, I felt stressed because I kept them waiting. And with pain it was even worse; in this profession you cannot avoid to sometimes cause pain. But, it was as if I felt that pain myself. That’s the strange thing in our profession: you are a “good” dentist when you haven’t hurt the patient, even when that means your treatment wasn’t optimal.

It’s in my nature to want to do everything myself. If I had others do things, I always had to check it myself and do it over anyway, so I was used to doing it myself straight away. Particularly so in my solo practice of course. But also in my private life I tend to be the first person that stands up when something has to be done. I am active in several community organizations, and also there I feel responsible that everything is done well.

At home I become more and more irritated. When I woke up, I already felt tired. Because I have to look in patients’ mouths in a concentrated way, I got eye problems. In the evening I could not stand watching TV after work. When we went on holidays as a family, it always took me days and days before I was used to big wide open space around me. And at the end of the holidays, when I was finally relaxed, I hated it that I had return to all these little mouths.

I had had a slight pain in my chest before. My physician advised me to slow down, but you know, our clinic agenda is always full. And I was used to being harsh to myself, I have always been. No staying home when you have the flu for me, you just take a pill. When others called sick, I always thought they were not suited to be a dentist. So I continued in the same way.

I must say my social environment did warn. My family, some friends. They saw me running and running. And also noticed my changing mood. I got angry outbursts more often, was irritated more easily. But I denied their remarks.

Then, one day, I broke. It was in busy time before the end of the year, after which some health insurance policies would change. So many patients wanted to have something fixed under the old policies. One patient called by telephone with a simple question about this insurance change. And I went mad! I kicked at the wall, shouted to the patient through the phone, yelled at my assistant! And then I broke out in tears, and I went home …

I had given everything I had for my patients for 15 years. And now I could no longer. That was so emotional. I have bee/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses