Chapter 7

Surgical Principles and Technique

Principles of:

- Painless surgery

- Asepsis

- Minimal damage

- Adequate access

- Arrest of haemorrhage

- Debridement (toilet of wounds)

- Drainage

- Repair of wounds

- Control and prevention of infection of wounds

- Support of the patient

The practice of surgery rests on certain fundamental principles which remain unchanged, though to apply them the surgeon may have to modify techniques to suit the anatomical field, the type of operation and the conditions obtaining at the time. The surgeon must have a clear and comprehensive knowledge of surgical physiology, the anatomy of the region being operated on and the pathology of the condition under treatment.

Principle of Painless Surgery

Today it is accepted that all surgery should be painless. This is important to avoid psychological and physical stress to the patient, which may predispose to shock, delay recovery and make surgery under local anaesthesia more difficult for the surgeon. In oral surgery, general anaesthetics are administered by a specialist in this field, whereas the oral surgeon is usually highly skilled in giving local anaesthetic injections.

It is outside the scope of this book to discuss the administration of local and general anaesthetics; however, the surgeon should strive to achieve local anaesthesia using block anaesthesia wherever possible, as this may save the patient considerable inconvenience (Figure 7.1). The choice between these will depend on surgical as well as medical considerations, and where doubt exists the decision should be made jointly with the anaesthetist. The patient and the anaesthetist may often have to be guided as to which is better in particular circumstances.

Figure 7.1 Position of needle for administration of infraorbital block. Note that this is consistent with the administration of a high infiltration above the maxillary canine.

The indications for general anaesthesia are: first, when there is an acute or subacute infection which it is not possible to treat using regional block anaesthesia; second, where the operation involves several quadrants of the mouth, is lengthy, difficult or of an alarming nature; third, for young children and adult patients who are unable to co-operate. General anaesthetics without intubation should not be used for procedures expected to last more than 5 minutes, although use of a laryngeal mask can prolong this safely up to 20 minutes. As an outpatient procedure this is now almost entirely restricted for the treatment of children. Day-case surgery, where the patient is intubated and the postoperative period supervised by the nursing staff, is suitable for operations that can be completed within 45 minutes, allowing the patient to make a full recovery before discharge home.

Local anaesthesia is suitable for many minor oral surgical procedures. It is indicated where the patient has eaten recently and does not wish to wait and in certain medical conditions (such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, COPD). The combination of local anaesthesia and sedation with intravenous benzodiazepines, such as midazolam, is useful for the nervous patient. This technique requires well-trained staff and adequate recovery facilities. It should be treated in a similar fashion to a general anaesthetic and the patients prepared in the same way.

Principle of Asepsis

Asepsis is the exclusion of micro-organisms from the operative field to prevent them entering the wound. The patient’s mouth, however, cannot be sterilised and remains a source of infection. A preoperative scaling and good oral hygiene practised before operation will reduce the chance of gross contamination; moreover patients seem to acquire a degree of immunity to their own oral flora.

The sterile instruments, fluids and dressings used in oral surgery are laid up on a trolley. Where pre-packed instruments are not used this must be done with sterile forceps. The surgeon and assistant should wear sterile disposable gloves and only those instruments laid on the trolley should be handled. A third person should be present to adjust the operating lights and position of the patient and obtain any further equipment required during the procedure. The patient’s skin and mouth should be prepared with antiseptic to eliminate some of the bacterial load and towelled to avoid contamination from hair and nose (see Chapter 6).

Principle of Minimal Damage

Inexperienced surgeons often pay too much attention to the tooth, cyst or tumour to be removed and too little to the tissues left after surgery is complete. Certain radical operations may regrettably require the sacrifice of vital structures, but this does not often apply in the orofacial region, and damage or loss of function as a result of carelessness or lack of foresight is inexcusable.

The commonest causes of trauma are poorly planned operations with ill-designed flaps, a careless approach to bone removal and tooth extraction, and excessive use of force by the surgeon or assistant in dissection, retraction of flaps and in the use of elevators, burs and chisels. These practices increase postoperative pain and swelling and delay healing. They not only interfere with healing but increase the possibility of infection because they leave behind pieces of dead bone, tooth and mutilated soft tissues.

Principle of Adequate Access

Incision and Flap

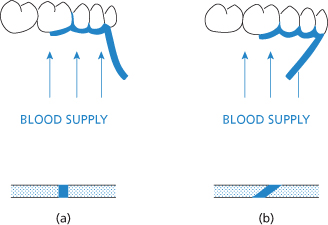

Access to the site of operation is gained by cutting the skin or mucous membrane and by dissecting through this incision to expose the underlying tissues. The site, size and form of the incision is planned to give the best possible approach with the least danger to important nearby structures. The operation completed, the flap has a second and equally important function, that of providing the first dressing to the wound. To do this it must be large enough to give easy access, be mobilised with sufficient subcutaneous tissue to give adequate support and bring with it a good blood supply. It should have healthy, clean edges that will heal by first intention. This means that, in the mouth, when the mucoperiosteum is reflected the mucosa and periosteum must not be separated. The incision must be so designed that it does not cut across the blood supply to the flap but includes the vessels that supply that area of skin or mucous membrane, otherwise the edges may slough and healing is delayed (Figure 7.2).

Figure 7.2 (a) Above: Correct design of the buccal flap to ensure a satisfactory blood supply to all parts. Below: Cross-section of satisfactory incision made with the scalpel blade vertical to the surface of the skin. (b) Above: Incorrect design of buccal flap. Below: Cross-section of an incision made with the scalpel blade held obliquely.

Where it covers a cavity in bone, it should be of such a size that when replaced the line of the incision rests securely on bone.

Incision

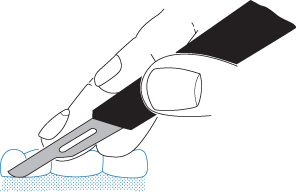

The scalpel is held in a pen-grip and the hand is supported against slipping. The incision is made with one firm, slow stroke of a sharp blade, which is kept vertical to the epithelial surface. The bow is used for cutting, where possible the point being kept above the skin or mucous membrane as a guide to the depth at which the incision is being made (Figure 7.3).

Figure 7.3 The scalpel held in the pen-grip and the bow of no. 15 blade used to make the incision. Note the fingers supported on the teeth.

The point is used at the beginning and end of the incision to ensure an even depth of cut along the whole length. Mucoperiosteum should be cut through its full thickness down on to bone at one stroke.

Dissection

The mucoperiosteal flap should be reflected with a periosteal elevator. An Ash or a Ward periosteal elevator may be used in this way; alternatively a Mitchell trimmer or Howarth raspatory may be used. Holding an instrument in both hands to both retract and elevate using a ‘knife and fork’ technique can be useful. The instrument is first inserted into the incision and, starting in the buccal sulcus where the periosteum is loosely attached, the first few millimetres at the edge of the flap are gently freed along its periphery. Thereafter, it is reflected evenly along its whole length by a clean movement, with the end of the chosen instrument pressed and kept firmly against the bone. Lifting movements are to be avoided as they tend to tear the tissues.

A skin flap is raised by separating it, with sufficient supporting tissue, from the underlying structures either by blunt dissection in a suitable tissue plane or sharp dissection using a scalpel or scissors. A combination of these techniques may also be employed. The essential point is to maintain an even depth of supporting tissue with an adequate blood supply and to avoid ‘buttonholing’ the flap. The deeper tissues are more usually explored by blunt dissection with either scissors or fingers, or where delicate structures are involved by separating each layer by gently packing wet gauze between them. Connective tissue, muscle and bone must be identified, laid open in turn, and all important structures identified and carefully preserved where possible.

Cutting of Bone

In oral surgery the cutting of bone to give access is done with burs, the efficiency of dental handpieces and sharp burs giving superlative control. The use of innovative equipment such as Piezo saws give excellent properties of minimal damage. The use of chisels, gouges, rongeurs and files is declining but may also be used on occasion.

Burs

Tungsten carbide burs of medium size, either rosehead (Ash 7–16) or fissure (Ash 7–12), are used. Satisfactory cutting with fine control can only be attained using high speeds and minimal pressure. To avoid overheating of the tissues and clogging of the bur, it must be irrigated with sterile saline.

Burs can be used in two ways, either to grind bone away or to remove blocks of bone. Grinding is done with rosehead or fissure burs preferably used with a gentle sweeping movement over the whole length of the area concerned, thereby leaving a smooth even edge. Blocks of bone are removed using fissure burs (Ash size 7) to make cuts through the cortex into the medulla round an area that can then be freed with osteotomes.

Piezo

Ultrasonic equipment has been developed to allow minimal damage to bone while exposing an area by removal of a block of bone. This is less likely to damage teeth and soft tissues.

Chisels and Osteotomes

These may be used in young patients, under 40 years of age, where the natural lines of cleavage along the ‘grain’ of the bone are present. In older patients (over 40 years) the use of c/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses